GM CROPS

GM corn in Belize

Genetically-modified crops (GM) have been embraced as a solution for the developing world’s agriculture and food problems because it believed that they will dramatically increase food production, reduce the need for pesticides, help produce drought-resistant crops that will grow on land regarded as unsuitable for agriculture, raise the incomes of farmers, and reduce disease by producing crops full of vitamin, minerals and other nutrients.

Genetic modification or engineering crops are ones that have been altered by splicing a desirable gene, such as one that resist pests, from one organism into another. About 70 percent of the engineered crops used today have been developed for herbicide resistance. Most of the rest are engineered to resist pest, many by being given genes that produce natural insecticides.

Worldwide sales of GM products rose $75 million to $1.5 billion in 1999, when 55 percent of the soy crop, 36 percent of the corn crop and 42 percent of the cotton crop in the United States was produced with GM products. Americans seem to little bothered by GM food They have been sold in the United States since the mid-1990s. About 60 percent of the products in supermarket shelves contain ingredients from GM soybeans, corn or canola. Japanese and Europeans are more suspicious of them.

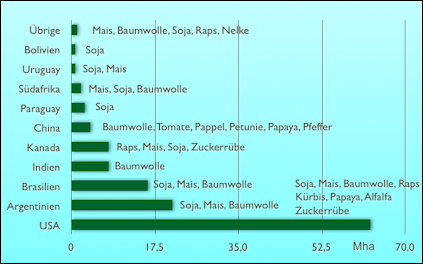

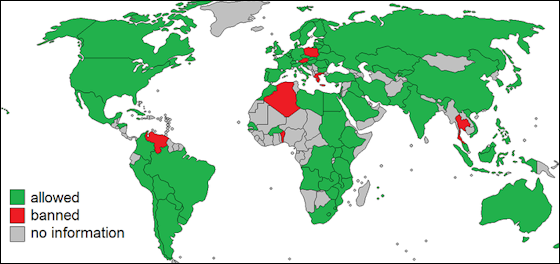

GM crops have been embraced in the United States, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, China and Australia but have not been widely used in the developing world because farmers can’t afford the high-priced GM seeds.

The top GM crops are soybeans, corn and cotton. Scientists have unraveled the gene sequence of nearly all the 50,000 or so genes in corn and soybeans. The edible products from GM crops goes mostly into animal feed.

Attention to GM crop issues when Starlink, GM corn that had not been approved for human consumption, showed up in some taco shells. By that time a large amount of Starlink corn from the United States has been sent to poor nations.

More than 20 countries grow GM crops for their high yields. Such crops are resistant to herbicides, and some are said to be resistant to even the strongest herbicides.Despite such risks, the use of GM crops is likely to increase worldwide. A set of international rules governing GM crops has been created through the adoption of the supplement to the biodiversity protocol for redressing damage caused to ecosystems by GM crops.

Types of GM Crops

GM products include strawberries and tomatoes with a gene from an Arctic flounder that prevents them dying in a frost; gene-altered soybeans produced by Monsanto that resist fungus and weed and a popular herbicide made by Monsanto; potatoes with a bacteria that is toxic to leaf chewing insects but not humans; corn strains that resist the European corn borer.

Genetically-modified (GM) versions of corn, soy beans, canola and cotton are now widely used. Just two engineered traits are sold: 1) resistance to glyphosate, a herbicide used to kill weeds and crops; 2) use of BT, a microorganism that produces chemicals that are toxic to insects not humans.

Bioengineers have developed rice stains that are dramatically more productive and nutritious than current stains. See bata-carotine golden rice under Rice

Scientists are working on making cancer-fighting broccoli, vaccine-delivering bananas, saturated-fat-free oils, allergy-free peanuts and soy products and vitamin-enriched, high-protein sweet potatoes and cassava for the poor. Bioengineering has also produced an “Enviropig” that produces manure with no polluting phosphorus; trees that produce pulp easily made into paper with harmful chemicals;

Arguments for GM Food

Thus far no one to anyone's knowledge has been harmed by GM products. GM food can greatly increase agricultural productivity and help feed hungry parts of the world by producing hardier, high-yield crops that are more nutritious and need fewer pesticides.

The advantage of GM crops has not been higher yields — yields from GM soy beans, for example, are 10 percent less than with high-yield soy bean varieties — but rather savings on chemicals and labor.

Many genetic modification are aimed at getting rid of the crop-destroying pests or diseases that destroy a large percentage of the world's crops and boosting crop yields to feed growing populations on shrinking amounts of agricultural land.

Some academics believed that GM crops have to be developed and marketed in a way that is most beneficial for the people it is supposed to help. Sachs has argued that it makes more sense for the West to assist the developing countries develop their own biotech infrastructure rather than dictating to them what they need. “We can’t presume our technologies will bail out the poor,” he told Time. “They need their own improved varieties of sorghum and millet, not genetically improved varieties of wheat and soybeans.”

Some scientists believe that GM crops have the potential to set off a second Green Revolution. With demand for food growing and the threat from shortages looming, scientists are pushing GM crops as an answer to the problem. In Europe, Asia and Africa, governments that had resisted importing GM crops and banned growing such crops on their soil are beginning to ease restrictions and even are starting to push ahead with their own projects. C.S. Prakash, a professor of plant genetics at Alabama’s Tuskegee University, told Reuters, , “Influential voices around the world are calling for a reexamination of the GM debate. Biotechnology provides such tools to help address food sustainability.”

Problems with GM Crops

Some people worry that genetic modification unleash unanticipated and uncontrollable forces that in a worst case scenario could produce some sort of monster crop could cause severe health or ecological problems. Many scientists believed is makes sense to err on the side of caution because we simply don’t know what the consequence of GM crops may be.

There are worries that GM crops could spread unpredictably and that genetic diversity will be compromised. Local varieties of corn in Mexico have already been contaminated by GM varieties even though GM corn are banned in Mexico. Mexico approved the use of GM corn in 2008 on a limited basis but only after a buffer zone was set up to protect native species.

Genetically-modified golden rice There are also worried that allergens might be introduced to foods and engineered crops could help insects build up a resistance to pesticides. Cotton bioengineered to withstand attacks from the cotton bollworm were introduced to north China around the year 2000. The cotton was engineered o produce a toxin — originally found in a soil bacterium called “Bacillus thuringiensis” — that was effective keeping the bollworm away and reducing the need for pesticide. [Source: Per Pinstrup-Andersen, Cornell University, Los Angeles Times]

Opponents of GM crops warned that the bollworms would develop resistance to the toxin and become more damaging than ever. That didn’t happen. Instead by eliminating the bollworms as a threat a new pest emerged — mirid bugs — that were not affected by the toxin and multiplied. Not only did they end up causing more damage than the bollworms they also devoured crops other than cotton such as grapes, apples, peaches and pears. Farmers handled the problem by using more pesticides than they did before the GM cotton was introduced.

The promises made about GM crops have not always turned out to be reality. Producing drought-resistant crops, for example, has turned out to be much harder than previously thought. Drought-resistant corn by Monsanto is slated to go on the market in 2012 but it is only 6 to 10 percent more effective than regular drought-resistant strains.

At study Cornell Universities that larva of Monarch butterflies could be killed by pollen from GM corn with built in pesticides.

Some critics charge that the greatest beneficiaries of GM crops are the biotech companies and corporate farmers. They complain about the high prices that large biotechnology companies charge for seeds for which they have patents.

Researchers say that a lot can still be achieved with traditional plant breeding techniques such as transgenic method, which is use to combat fungus and insects, and marker-assisted breeding, in which genes associated with desirable traits are tagged to speed up the breeding process.

Some studies suggest that the proliferation of GE crops and the pesticide used on them has led to the development of “super weeds” resistant to that pesticide.

GM Crops in the United States

The USDA has approved 81 genetically-engineered (GE) crops — it has never denied a proposal — and 22 applications are pending. The GE (more or less the same as GM) industry argues that farmers should be free to grow the crops because they do not harm other plants and say it is the best way to feed a growing global population because farmers can raise more food and use fewer pesticides and less fertilizer. “Biotechnology can help crops thrive in drought-prone areas, improve the nutrition content of foods, grow alternative energy sources and improve the lives of farmers and rural communities around the globe,” Jim Greenwood, head of Biotechnology Industry Organization, said this year.

Since GE crops debuted in 1992, they have been embraced by many U.S. farmers. The vast majority of soy, corn, cotton and canola seed is genetically engineered. Although GE sugar beets were temporarily taken out of production by a court ruling, they had captured 95 percent of the market.

Foods made from GE crops are not labeled, but the typical American consumes them regularly because most processed products contain ingredients made from modified soy, corn, canola and sugar beets.

Sharon Bomer, an executive vice president at Biotechnology Industry Organization, told the Washington Post, “There is deep appreciation” in the GE industry for the need to minimize the spread of the crops. She said organic farmers must protect their crops. “The burden is on them,” she said. But GE critics are not satisfied. “To say “just trust me” is rather absurd when we’re talking about profit-related companies,” said George Siemon, chief executive of Organic Valley, a major organic farmers’ cooperative.

Acceptance of GM crops

U.S. Battle Between GM Crops and Organics

Lyndsey Layton wrote in the Washington Post, “Two thriving but opposing sectors — organics and genetically engineered crops — have been warring on the farm, in the courts and in Washington. Organic growers say that, without safeguards, their foods will be contaminated by genetically modified crops growing nearby. The genetic engineering industry argues that its way of farming is safe and should not be restricted in order to protect organic competitors. [Source: Lyndsey Layton, Washington Post March 23, 2011]

In March 2011, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced several decisions that took the side of the genetically engineered (GE) crop industry, namely approving genetically-modified alfalfa and a modified corn to be made into ethanol, and he gave limited approval to GE sugar beets.

The two sides are not clashing over the ethics or safety of genetic engineering, in which plants are modified in the laboratory with genes from another organism to make them more pest-resistant or to produce other traits. Instead, the argument is over the potential for contamination: pollen and seeds from GE crops can drift across fields to nearby organic plants. That has triggered fears that organic crops could be overtaken by modified crops. Contamination can cost organic growers — some overseas markets, for example, have rejected organic products when tests showed they carried even trace amounts of GE material.

Critics of genetic engineering refer to a 2000 incident in which a GE corn meant for animal feed infiltrated tortillas, corn chips and other foods. More than 300 foods were recalled, and farmers were awarded a $110 million settlement for lost income.

Syngenta, maker of the GE corn to be used for ethanol, has said it will reduce risk of contamination by requiring farmers to grow the crop near ethanol plants and sell only to those plants, among other measures.

GM Cotton Crops

Cotton bioengineered to withstand attacks from the cotton bollworm were introduced to north China around the year 2000. The cotton was engineered o produce a toxin — originally found in a soil bacterium called Bacillus thuringiensis “that was effective keeping the bollworm away and reducing the need for pesticide. [Source: Per Pinstrup-Andersen, Cornell University, Los Angeles Times]

Opponents of GM crops warned that the bollworms would develop resistance to the toxin and become more damaging than ever. That didn’t happen. Instead by eliminating the bollworms as a threat a new pest emerged — mirid bugs — that were not affected by the toxin and multiplied. Not only did they end up causing more damage than the bollworms they also devoured crops other than cotton such as grapes, apples, peaches and pears. Farmers handled the problem by using more pesticides than they did before the GM cotton was introduced.

Cotton farmers in Arizona faced the same dilemma after they began planting Bt cotton in 1996 and the absence of pesticides made fields safe for lygus bugs, a type of mirid bug. Farmers there dealt with the problem by using targeted pesticides that spared insects like ladybugs that feed on lygus bugs, said University of Arizona entomologist Bruce Tabashnik. [Source: Karen Kaplan, Los Angeles Times , May 16, 2010]

"The lesson here is that Bt cotton is not a silver bullet," said Tabashnik, who nonetheless endorses the crop for its role in reducing the need for anti-bollworm pesticides.There's no reason to think that other types of genetically engineered crops would be immune to this type of problem, Pinstrup-Andersen said. Ultimately, he said, the solution is to develop genetically modified plants that are resistant to a variety of insects, but that will be a continuous process. "We have to constantly stay ahead of those things," he said.

Gates Foundation Gives $18.6 Million to Develop GM Rice and Cassava

In April 2011, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation announced two grants totaling $18.6 million to support the development of rice and cassava with enhanced micronutrients, offering disadvantaged people in Asia and Africa better nutrition and the opportunity to lead healthier, more productive lives. [Source: “Nutritious Rice and Cassava Aim to Help Millions Fight Malnutrition.” Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Press Release, April 13, 2011]

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) was awarded $10.3 million to develop Golden Rice, a type of rice containing beta carotene, which the body converts to vitamin A — a vital nutrient that more than 90 million children in Southeast Asia lack. Building on previous funding from the foundation, the grant will support efforts to develop and evaluate Golden Rice varieties for the Philippines and Bangladesh in partnership with other organizations, including Helen Keller International, the Philippines Rice Research Institute, and the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute. In addition to evaluating the safety of different varieties, the project will work to secure regulatory approval, perform tests on the nutritional benefits of these varieties, and design a sustainable delivery program and plans to apply for regulatory approval of the varieties as early as 2013 in the Philippines and 2015 in Bangladesh.

The foundation also awarded $8.3 million to the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center for the second phase of its BioCassava Plus project, which aims to boost the nutritional value of cassava. While cassava is a staple crop consumed by more than 250 million people in Africa, it offers limited nutritional value, leaving both children and adults at risk of severe health problems. The grant builds on previous funding from the foundation and will support cassava-enrichment efforts in partnership with a number of organizations, including the Nigerian National Root Crop Research Institute and the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute.

"While the consequences of malnutrition are dire, especially for children, there is enormous potential for nutritionally enhanced foods to make substantial improvements to people's health," said Sylvia Mathews Burwell, president of the foundation's global development program. "If small farmers choose to grow these new improved crops, we expect to see not only their health improve, but also a ripple effect that means more prosperous lives."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012