CORRUPTION IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

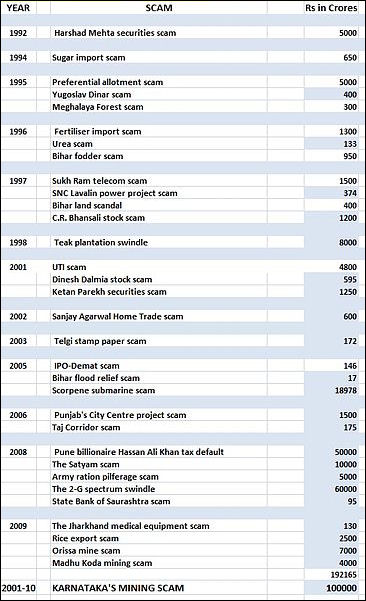

List of scams in India from 1992 to 2010 Corruption is a major problem in developing countries, especially ones with nationalized economies, authoritarian governments and recently democratized societies. Studies have shown that cultures around the world have similar perceptions that corruption is fundamentally wrong. Scholars therefore perceive corruption as not a cultural flaw but a symptom of a sick state.

Some scholars believe that corruption helps "grease the wheels" of a an otherwise inefficient bureaucracy and economy. Companies that do business in places were corruption exists often say they have no choice but to pay bribes and kickbacks because that is the way business is done.

Most scholars believe that corruption hinders development and is inefficient economically. A Harvard study that undermines the "grease" theory found that "firms that pay more bribes are also likely to spend more, not less, management time with bureaucrats negotiating regulations and face a higher, not lower, cost of capital."

Solutions to corruption include raising the salaries of bureaucrats and policemen so they don’t depend on corruption for income and increasing transparency in government and business. Scholars debate whether corruption is a stage that countries pass through or condition that paralyzes a country for a long time.

Large Scale and Small Scale Corruption in the Developing World

Large scale corruptions often revolves around agreements between major local or foreign business and high ranking government officials or members of their family.

Corruption is often times the highest in countries with large amounts of oil, natural gas and natural resources. Columbia economist Jeffrey Sachs wrote governments in countries with lot resources “can live off their export earnings without having to “compromise” with their own societies. The natural resources are therefore not only a target of corruption but also are an instrument for holding on to power. Many foreign companies, intent on cashing in, fuel the pathology of corrupt regimes by peddling in bribes and political protection.”

Corruption is common in the police force, the bureaucracy, customs service, the judiciary, regulatory agencies and utilities. Small scale corruption takes the form of things like customs officials taking money to quicken the immigration procedure; electric company clerks taking money to stop overcharging; police officers taking a bribe for a minor infraction and not writing a ticket; bureaucrats taking money to get their signature on a document; and repairmen taking money to install a phone or get a wait-listed item. Bribery is very common in the schools. The parents of failing students often make teachers very generous offers or give them nice gifts on the Teachers Day holiday. The going rate for a "pass" may be the equivalent of about $100 while and "A" goes for as much as $500. In an attempt to crack down on such practices, governments do things like hand out special grade books to teachers that have to be filled out with permanent ink. If a teacher makes a mistake — wrote down a "C" instead of "B" for example — the entire grade book had to be scraped and a new one filled out.

A survey by Transparency International in 64 countries in 2004 found that people regarded political parties as the most corrupt institutions followed by parliaments with police and the court system tied for third. In the same survey 57 percent of the respondents said that large-scale corruption committed by political leaders and major corporations were major problems while small-scale corruption defined as payments of bribes in everyday life was deemed a serious problem by 45 percent.

Corruption, Politicians, Police and Bureaucrats in the Developing World

Corrupt legislation by Vedder-Highsmith Politicians around the world routinely trade favors for support needed to win elections, and often use that cash to buy the votes of desperately poor people. Cronyism and nepotism are often manifestations of a patronage system in which successful candidates are tacitly required to reward their supporters. In some cases cabinet reshuffles are conducted not to put the most qualified people in high positions but to distribute high ranking positions among cronies. Abuse of power and scandals arise when these people get greedy and believe their positions and support of the leader will protect them.

Bureaucrats use licenses, approval and mandatory signatures to enrich themselves. Each exchange with a member of the public is chance to make money. Government contracts, clearing goods through customs and privatizing companies are all seen as opportunities to extract large bribes.

With salaries at only $200 a month bureaucrats find it hard to resist temptation. Generally the higher the position of the bureaucrat, the greater the value of his approval and the higher the cost. Bribes are often taken by low level bureaucrats who take a cut and distribute the rest to their superiors up the chain of command. Bureaucrats who refuse to take bribes risk losing their jobs.

Sometimes bureaucrats are so greedy the projects they are overseeing are not completed. One villager told reporter Richard Critchfield that "our irrigation system failed because the minister took his ten per cent, the engineer his ten percent and the village chief his ten percent, so there wasn't enough money left to buy the water pipes."

Police often have low salaries and are expected to take bribes to make a decent living. "Let's say a policeman gives you a ticket," a young woman told National Geographic. "He has a wife and four children — how could you imagine that this person could live decently on his salary of maybe [$230] a month. So everybody understands that instead of paying the parking ticket....to the state, you give him money instead not to write the ticket."

Police superintendents often send their officers out with the expressed purpose of collecting payoffs. After running a road block a driver told a journalist, "Only highway police have authority to stop us. These other guys, local police, different color uniform, bad guys. Boss sends them out to collect bribe. They come back with money, he takes some and they keep the rest."

Government by Crime Syndicate

Anti-corruption poster

Nouakchott. Mauritania Sarah Chayes, a development expert, wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In early 2010, I was asked to make a presentation to a counter-narcotics symposium at the Marshall Center in Germany. In attendance were several hundred high-ranking military and law enforcement officers from around the world. I dutifully explained the opium economy in Afghanistan, which I've had a chance to observe during nearly a decade living and working in Kandahar. But I could not resist inserting two slides at the end of the talk. They depicted the phenomenon that really interests me: the increasingly structured capture of the Afghan government by what amounts to a set of interlocking, vertically integrated criminal networks. [Source: Sarah Chayes, Los Angeles Times, September 25, 2011. Chayes runs a cooperative that produces soap and skincare products in Kandahar, Afghanistan. She is the author of "The Punishment of Virtue: Inside Afghanistan After the Taliban" and designed an anti-corruption strategy for the command of the international forces.]

I have watched the phenomenon evolve over the last 10 years. At first, there was a furtive testing of the limits, as Kalashnikov-toting ruffians shook down travelers for "sweets" (as extorted bribes are prudishly called). Over time, the corruption expanded and evolved, and today, Afghanistan is controlled by a structured, mafiaesque system, in which money flows upward via purchase of office, kickbacks or "sweets" in return for permission to extract resources (of which more varieties exist in impoverished Afghanistan than one might think) and protection in case of legal or international scrutiny. Those foolish enough to raise objections are punished. The result is a system that selects for criminality, excluding and marginalizing the very men and women of probity most needed to build a sustainable state.

When I finished my presentation, to my astonishment, the participants rose in a standing ovation. Many came down to the front of the room to talk further. "You just described my country," they chorused. was stunned. For so long had my nose been buried in Afghanistan and its peculiarities that I had not realized I was experiencing just a sliver of a global phenomenon. As I spoke to these symposium participants (who came from Nigeria, the former Soviet republics, Pakistan and elsewhere), I couldn't help but notice a correlation between mafia government and the existence of violent religious extremism. And I realized that the phenomenon of public corruption — often pooh-poohed or viewed as a part of the ambient "culture" of South Asians, or Muslims or whomever — poses a substantial threat to international security.

Then my musings led me further afield, to consider political philosophy. Was mafia government, I began to wonder, also posing a threat to the entire phase of political history in which we live?...One of the key elements of rule-based systems has been legal recourse against perceived abuse of power. But if such a rule-based system is captured by a criminal network, thus injecting an intolerable degree of the arbitrary into the award of opportunity or benefit, then citizens are denied fair recourse. To whom, then, should they turn for redress of legitimate grievances?

But fortunately this tendency doesn't have to be the end of the story. In 2010, for example, Kyrgyzstan led the way with massive anti-corruption demonstrations. The Arab Spring has been the biggest international phenomenon since the fall of the Berlin Wall, and was largely motivated by the identical grievances that have animated Anna Hazare's supporters in India. Moroccans carry brooms to their rallies; Egyptians cry out for the prosecution of corrupt officials; Tunisians demand the return of assets expropriated for private benefit by the Ben Ali clique.

The ultimate results of these experiments — in government overthrow, constitutional transformation or the establishment of a truly independent oversight mechanism — remain in doubt. But it would behoove all of us to redouble our efforts to ensure their success. For failure could spell a fatal setback for the whole enterprise of government by human reason.

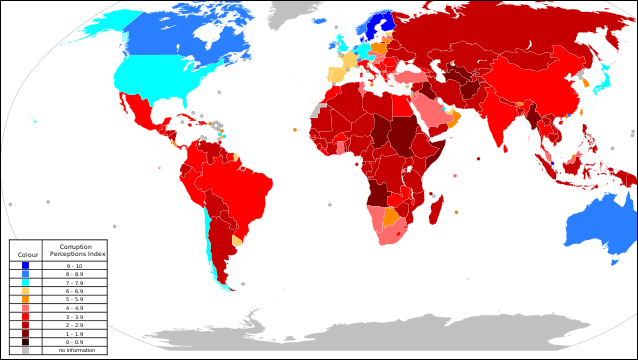

Index of perception of corruption, 2010

Combating Corruption in the Developing World

In 1996, World Bank President James Wolfensohn called corruption a “cancer” on the global economy and said it was time to “put teeth” into anti-corruption efforts. Before that time the World Bank had forbidden the use of the word “corruption — on its official documents.

Tackling corruption requires a government that is responsive to the people and a media and social organizations that look out for the interests of the general public. There also needs to be a certain amount of political will, which is difficult to find considering that so many politicians rely on corruption to survive and prosper.

Sachs wrote in Time: “The best answer, both in theory and practice, is to find ways to hold government accountable to the people that they serve. Elections are obviously one method, though campaign financing can be a source of corruption...Privately owned newspapers, independent radio and television networks, trade unions, churches, professional societies and other groups within a civil society provide a bulwark against despotism....Poor countries achieve lower levels of corruption when civil rights are protected. When you have the freedom of assembly, to speak and to publicize the views, society benefits not only by increasing the range of ideas that are debated, but also by keeping corruption in check.”

But unfortunately in many developing countries the government is not very responsive and institutions that would keep corruption in check are weak: Sachs wrote: “the result is a trap in which poverty causes bad governance and bad governance causes poverty...A two-way spiral downward that can lead to such extreme depravation that the government lacks computers telephones, information and trained civil servants and couldn’t function honestly even if it wanted to.”

Although some progress has been in some countries and a great deal of time, energy and money has been devoted to corruption-fighting efforts, corruption remains entrenched as ever and in some places is worse than it has ever been.

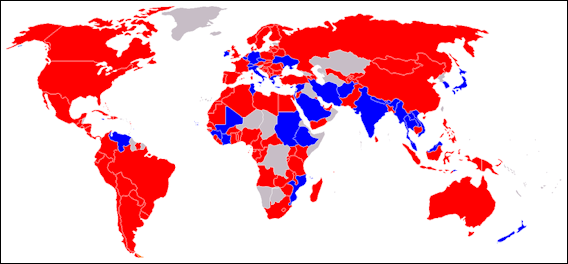

Ratifiers of the UN anti-corruption treaty

Crime and Justice in the Developing World

Sometimes in slum areas there is little crime because there is little to steal. People tend to much more concerned about fires. In villages there is even less crime because there is also little to steal and everyone knows everyone.

A study by the United Nations crime agency found that people from 127 countries are exploited by people in 37 countries by human traffickers for sexual exploitation and forced labor. Most are women and children recruited in their homelands and transported through other countries and exploited in “destination countries.” Victims are mostly from Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, southern and southeastern Asia, the former Soviet Union and southeastern and central Europe. Many victims end up in developed countries in western Europe and in the United States and Japan.

Many of people in jail in developing countries have not been convicted of any crime and are awaiting trial. Some have been waited in jail for years.

For many people the justice system is a hurdle that has to be overcome. Mathew Miller wrote in the New York Times Magazine, "The poor live outside the law...because living within the law is impossible: Corrupt legal systems and warped rules force those at the bottom...to spend years leaping absurd hurdles to do things by the book."

Police, Corruption and Torture

The police have a reputation for being corrupt. Police often have low salaries and are expected to take bribes to make a decent living. "Let's say a policeman gives you a ticket," a young woman told National Geographic. "He has a wife and four children — how could you imagine that this person could live decently on his salary of maybe [$230] a month. So everybody understands that instead of paying the parking ticket....to the state, you give him money instead not to write the ticket."

Police superintendents often send their officers out with the expressed purpose of collecting payoffs. After running a road block a driver told a journalist, "Only highway police have authority to stop us. These other guys, local police, different color uniform, bad guys. Boss sends them out to collect bribe. They come back with money, he takes some and they keep the rest."

Many people have a relative or friend in the police that helps them get out of trouble.

The secret police and government security forces in many countries are not held in high regard by human rights organizations. They have been accused of starving, beating, and shocking interrogated prisoners as well as hanging them by their wrists until their joints were pulled out of their sockets.

Police in some places have abandoned traditional forms of torture, interrogation and delivering shocks with cattle prods and wires connected to are batteries. They now use hand-held stun guns that deliver powerful electric shocks of up to 50,000 volts. Designed for police use, these stun guns are marketed by 100 companies worldwide and many sells for less than $200.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012