DEVELOPMENT AND FOREIGN AID

Wealthy nations and international organizations such as the World Bank spend more than $55 billion annually on programs aimed at helping the poor mostly in developing countries. Every year there are highly publicized meetings in which donor countries pledge billions to help countries in need.

The development approach in developing world has largely taken place in two phases: first halting population growth, reducing disease and raising literacy and second introducing skill training, technology development and export economies. Traditionally aid agencies have tended to fund rural projects — such as digging wells, building schools and planting trees — rather than urban ones.

Many experts believe that the developing world's environmental and economic problems can only be fixed by tackling by addressing social problems first. Also, something that aid workers have learned through experience is that large, big money projects shoved down local people” throats often don’t work or cause as much harm as good while small projects, worked out with the involvement of local people are more successful.

Sometimes developed countries are accused of failing to actually come with the cash for pledges that they make. The United States, Japan and the European Union have been criticized by the United Nations for reneging on their promises to supply aid to poor countries. In addition to this donor countries are giving relatively less than they gave in the past. According to Oxfam the amount of aid given to poor countries by rich countries — based on the proportion of the rich countries’s income — is half what it was in the 1960s: 0.24 percent in 2004 compared to 0.48 percent in 1960-65.

Britain has a $11 billion aid budget. In 2010 the British government decided to reduce aid to emerging nations like China, Russia and India and instead give more money to countries like Pakistan where there is more need or political instability and where Britain has clear interests.

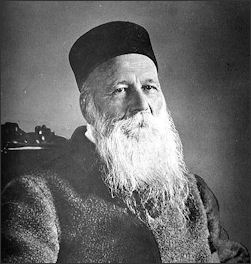

The Red Cross, Florence Nightingale and Origins of Humanitarian Aid

Jean Henri Dunant Philip Gourevitch wrote in The New Yorker, “The godfather of modern humanitarianism was a Swiss businessman named Henri Dunant, who happened, on June 24, 1859, to witness the Battle of Solferino, which pitted a Franco-Sardinian alliance against the Austrian Army in a struggle for control of Italy. Some three hundred thousand soldiers went at it that day, and Dunant was thunderstruck by the carnage of the combat. But what affected him more was the aftermath of the fight: the battlefield crawling with wounded soldiers, abandoned by their armies to languish, untended, in their gore and agony. Dunant helped organize local civilians to rescue, feed, bathe, and bandage the survivors. But the great good will of those who volunteered their aid could not make up for their incapacity and incompetence. Dunant returned to Switzerland brooding on the need to establish a standing, professionalized service for the provision of humanitarian relief. Before long, he founded the Red Cross, on three bedrock principles: impartiality, neutrality, and independence. In fund-raising letters, he described his scheme as both Christian and a good deal for countries going to war. “By reducing the number of cripples,” he wrote, “a saving would be effected in the expenses of a Government which has to provide pensions for disabled soldiers.” [Source: Philip Gourevitch, The New Yorker, October 11, 2010]

Humanitarianism also had a godmother... She was Florence Nightingale, and she rejected the idea of the Red Cross from the outset. “I think its views most absurd just such as would originate in a little state like Geneva, which can never see war,” she said. Nightingale had served as a nurse in British military hospitals during the Crimean War, where nightmarish conditions — septic, sordid, and brutal — more often than not amounted to a death sentence for wounded soldiers of the Crown. So she was outraged by Dunant’s pitch. How could anyone who sought to reduce human suffering want to make war less costly? By easing the burden on war ministries, Nightingale argued, volunteer efforts could simply make waging war more attractive, and more probable.

It might appear that Dunant won the argument. His principles of unconditional humanitarianism got enshrined in the Geneva Conventions, earned him the first Nobel Peace Prize, and have stood as the industry standard ever since. But Dunant’s legacy has hardly made war less cruel. As humanitarian action has proliferated in the century since his death, so has the agony it is supposed to alleviate. When Dunant contemplated the horrors of Solferino, nearly all of the casualties were soldiers; today, the U.N. estimates that ninety per cent of war’s casualties are civilians.

Biafra and the Early History of Modern Humanitarian Aid

Starved girl in Biafra Philip Gourevitch wrote in The New Yorker, “In Biafra in 1968, a generation of children was starving to death. This was a year after oil-rich Biafra had seceded from Nigeria, and, in return, Nigeria had attacked and laid siege to Biafra. Foreign correspondents in the blockaded enclave spotted the first signs of famine that spring, and by early summer there were reports that thousands of the youngest Biafrans were dying each day. Hardly anybody in the rest of the world paid attention until a reporter from the Sun, the London tabloid, visited Biafra with a photographer and encountered the wasting children: eerie, withered little wraiths. The paper ran the pictures alongside harrowing reportage for days on end. Soon, the story got picked up by newspapers all over the world. More photographers made their way to Biafra, and television crews, too. The civil war in Nigeria was the first African war to be televised. Suddenly, Biafra’s hunger was one of the defining stories of the age — the graphic suffering of innocents made an inescapable appeal to conscience — and the humanitarian-aid business as we know it today came into being. [Source: Philip Gourevitch, The New Yorker, October 11, 2010]

“There were meetings, committees, protests, demonstrations, riots, lobbies, sit-ins, fasts, vigils, collections, banners, public meetings, marches, letters sent to everybody in public life capable of influencing other opinion, sermons, lectures, films and donations,” wrote Frederick Forsyth, who reported from Biafra during much of the siege, and published a book about it before turning to fiction with “The Day of the Jackal.” “Young people volunteered to go out and try to help, doctors and nurses did go out to offer their services in an attempt to relieve the suffering. Others offered to take Biafran babies into their homes for the duration of the war; some volunteered to fly or fight for Biafra. The donors are known to have ranged from old-age pensioners to the boys at Eton College.” Forsyth was describing the British response, but the same things were happening across Europe, and in America as well.

Stick-limbed, balloon-bellied, ancient-eyed, the tiny, failing bodies of Biafra had become as heavy a presence on evening-news broadcasts as battlefield dispatches from Vietnam. The Americans who took to the streets to demand government action were often the same demonstrators who were protesting what their government was doing in Vietnam. Out of Vietnam and into Biafra — that was the message. Forsyth writes that the State Department was flooded with mail, as many as twenty-five thousand letters in one day. It got to where President Lyndon Johnson told his Undersecretary of State, “Just get those nigger babies off my TV set.”

That was Johnson’s way of authorizing humanitarian relief for Biafra, and his order was executed in the spirit in which it was given: stingily. According to Forsyth, by the war’s end, in 1970, Washington’s total expenditure on food aid for Biafra had been equivalent to “about three days of the cost of taking lives in Vietnam,” or “about twenty minutes of the Apollo Eleven flight.” But Forsyth, who was an unapologetic partisan of the Biafran cause, reserved his deepest contempt for the British government, which supported the Nigerian blockade. Even as Nigeria’s representative to abortive peace talks declared, “Starvation is a legitimate weapon of war, and we have every intention of using it,” the Labour Government in London dismissed reports of Biafran starvation as enemy propaganda. Whitehall’s campaign against Biafra, Forsyth wrote, “rings a sinister bell in the minds of those who remember the small but noisy caucus of rather creepy gentlemen who in 1938 took it upon themselves to play devil’s advocate for Nazi Germany.”

aid for orphans in Malawi The Holocaust was a constant reference for Biafra advocates. In this, they were assisted by Biafra’s secessionist government, which had a formidable propaganda department and a Swiss public-relations firm. The cameras made the historical association obvious: few had seen such images since the liberation of the Nazi death camps. Propelled by that memory, the Westerners who gave Biafra their money and their time (and, in some cases, their lives) believed that another genocide was imminent there, and the humanitarian relief operation they mounted was unprecedented in its scope and accomplishment.

In 1967, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the world’s oldest and largest humanitarian nongovernmental organization, had a total annual budget of just half a million dollars. A year later, the Red Cross was spending about a million and a half dollars a month in Biafra alone, and other N.G.O.s, secular and church-based (including Oxfam, Caritas, and Concern), were also growing exponentially in response to Biafra. The Red Cross ultimately withdrew from the Nigerian civil war in order to preserve its neutrality, but by then its absence hardly affected the scale of the operation. Biafra was inaccessible except by air, and by the fall of 1968 a humanitarian airlift had begun. The Biafran air bridge, as it was known, had no official support from any state. It was carried out entirely by N.G.O.s, and all the flying had to be done by night, as the planes were under constant fire from Nigerian forces. At its peak, in 1969, the mission delivered an average of two hundred and fifty metric tons of food a night. Only the Berlin airlift had ever moved more aid more efficiently, and that was an Air Force operation.

The air bridge was a heroic undertaking, and a stunning technical success for a rising humanitarian generation, eager to atone for the legacies of colonialism and for the inequities of the Cold War world order. In fact, the humanitarianism that emerged from Biafra — and its lawyerly twin, the human-rights lobby — is probably the most enduring legacy of the ferment of 1968 in global politics. Here was a non-ideological ideology of engagement that allowed one, a quarter of a century after Auschwitz, not to be a bystander, and, at the same time, not to be identified with power: to stand always with the victim, in solidarity, with clean hands — healing hands. The underlying ideas and principles weren’t new, but they came together in Biafra, and spread forth from there with a force that reflected a growing desire in the West (a desire that only intensified when the Berlin Wall was breached) to find a way to seek honor on the battlefield without having to kill for it.

Emergency Aid

aid delivered by MH-60S Knighthawk helicopter Foreign aid for disasters often arrives in the form of food, blankets, tents, warm clothes, heating fuel, water programs, health care, schools, books and even soccer balls.

Red Cross rations usually include rice, wheat or corn, biscuits with protein supplements, vegetable oil, blankets and jerry cans used for fetching water.

Most food aid comes in the form of cereals such as wheat, rice and corn. In the past few years supplies of these cereals have shrunk and gotten more expensive. This means that aid groups have to spend more on them and make cut backs in other forms of aid they can provide.

Food Aid

Providing food aid has become costlier and more difficult as food prices have risen, the dollar has slumped and food has gone to make biofuels.

Many NGOs and aid agencies prefer cash to food aid. With money in hand they can purchase food produced near the areas in need ands get it there faster and help local economies. Some groups sell the food that is donated to them to finance their programs. Groups like CARE say they do this because they need the money more than the food with the money being more useful in running long-term sustainable projects. The money also prevents them from having to lay off workers.

Prolonged exposure to food aid can drive prices down and discourage farmers from growing their own crops. Some NGOs are displeased enough with the situation they have begun turning down food aid.

See Global Food Crisis

Food Aid from the United States

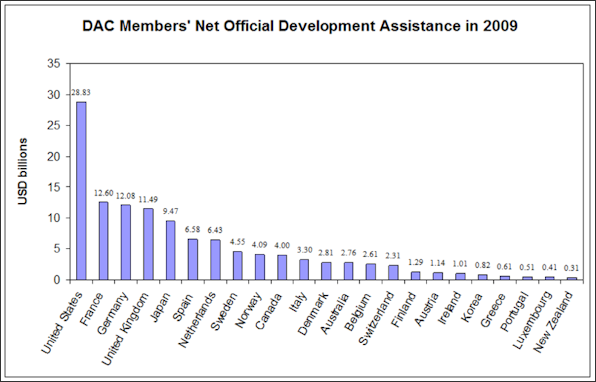

American humanitarian aid in Kenya The United States provides half the world’s food aid. Legal restrictions and bureaucracy in the United States require much of the aid to be the in form of American crops. Texas-grown sorghum can take as long as six months to reach places in sub-Sahara Africa, arriving long after it is most desperately needed, in the worst cases, leaving many people dead. On top of that prolonged presence of U.S. Food aid can overwhelm local markets and drives prices down, hurting local farmers. [Source: Philip Gourevitch, The New Yorker, October 11, 2010]

Typically with American food aid the U.S. government buys food grown in the United States. The food is shipped overseas mostly on American-flagged ships. At its destination the food is donated to nonprofit aid groups. A spokesman for Oxfam America told U.S. News and World Report, “While America provides half of the world’s food aid, this generosity is undermined by legal restrictions and bureaucracy, as food must be purchased in the United States and transported on U.S.-flagged ships.” The policy is in place in part to help American farmers and shippers.

Aid groups have criticized the system as being inefficient as well as unfair. CARE and the Catholic Relief Services — who rank first and second in money raised under the current system — complain they recover only 70 to 80 percent of what the United States paid for commodities and shipping. In 2007, CARE turned down $45 million of food aid from the United States.

Eradicating Poverty Through Profits

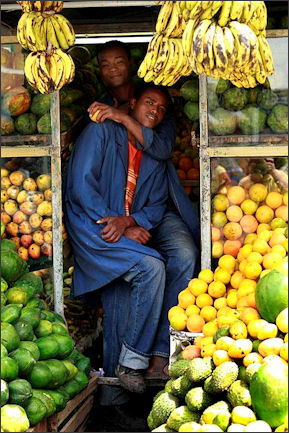

Ethiopian fruit vendor C.K Prahalad, author of “Competing for the Future” and “The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits” , is a proponent of using business models to tackle poverty. He rejects the notion that poor need to be wards of the state and treated as charity cases supplied with handouts. He says their interests would be better served by companies and entrepreneurs trying to make money off them and pulling them to into world market.

Prahalad has been named one of the top 10 management thinkers in the world and his ideas been endorsed by the likes of Bill Gates and former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright. As proof that his strategy works he sites a number of case studies in which companies have developed successful strategies for marketing products and service to the poor which both benefit the poor and earn the companies profits.

Prahalad calls the 4 billion people living on less than $2 a day the bottom of the economic pyramid and estimates that their worth is equal to $12.5 trillion annually, more than GDPs of Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Japan combined.

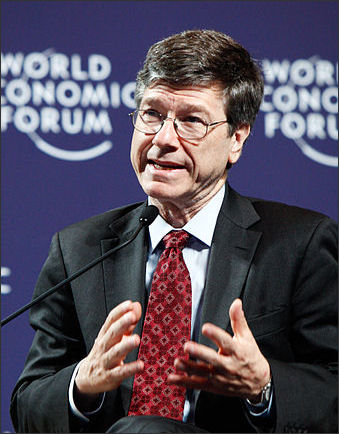

Jeffrey Sachs

One of the primary thinkers and policy makers in the drive to help the poor is Jeffrey Sachs, an economist who was a professor at Harvard for 22 years before he became head of Columbia University’s Earth Institute and the leader the United Nations Millennium Project, two programs which have brought scientists, economists, and government policy makers together to tackle big problems like world poverty, health and global warming.

Sachs became a tenured professor at Harvard at 28. He made a name for himself helping to turn around troubled economies in Bolivia and Poland and was involved to the transformation of the Russian economy to a market system after the collapse of the Soviet Union. He is currently involved in trying to turn sub-Sahara Africa around, which so far has failed to prosper and develop in the same way that Asia has.

Sachs is a friend of Bono; advised Pope John Paul II on globalization; set up a global fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria; and is involved in tacking global warming and other environmental problems.

Sachs is a major advocate of the view that everything is related and to tackle economic problems one has to address environmental, government, education, health care and infrastructure issues. He also says to make progress requires both big-picture schemes developed by aid agencies and rich countries and initiative and input on the local level to do things like collect rainwater and plant nitrogen-fixing trees.

Jeffrey Sachs’s Policies

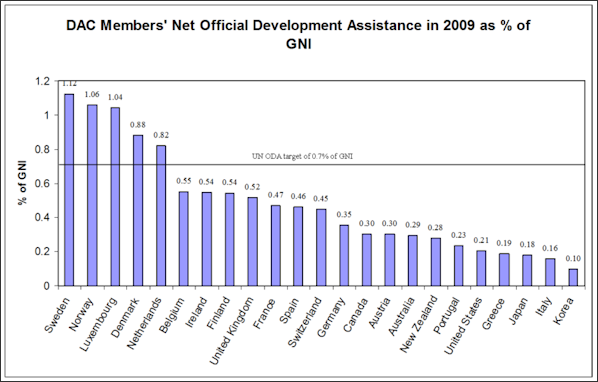

Jeffrey Sachs Sachs is the architect behind the Millennium Project plan to halve world poverty and hunger by 2015 by calling on rich countries to double their financial assistance to the poor, raising annual aid to 0.7 percent of worldwide GNP. His proposals are outlined in detail in his book “The End of Poverty” (Penguin Press, 2005).

Sachs advocates giving money to developing countries to improve health care, primary schooling and other services in the form of grants rather than loans and argues that the money should be guaranteed for long periods as long as certain performance targets are met. Sachs also supports the idea of giving money to countries that are well governed and not giving money to countries that are not.

Sachs believes that a primary goal should be to provide the Big Five basic needs: 1) improving agriculture, with improved seeds, fertilizers and crop storage bins; 2) improving basic health by building clinics and making sure they have basic supplies and staff members that promote practices such as using mosquito nets and condoms; 3) investing in education and doing things like offering school lunches to make sure students come; 4) providing energy; and 5) providing clean water and sanitation.

To achieve poverty reduction Sachs argues that nine steps need to be taken: 1) making a commitment to the goal of getting rid of poverty; 2) adopting a plan of action; 3) raising the voice of the poor; 4) redeeming the U.S. role in the world; 5) rescuing the IMF and World Bank; 6) strengthening the United Nations; 7) harnessing global science; 8) promoting sustainable development; and 9) making personal commitments.

Many feel what is needed most is to funnel money towards village-based water programs, developing a vaccine for malaria, provide cheap AIDS drugs and mosquito nets, fund school feeding programs and figure out ways to bypass corrupt local governments.

Piece-Meal Approach to Development

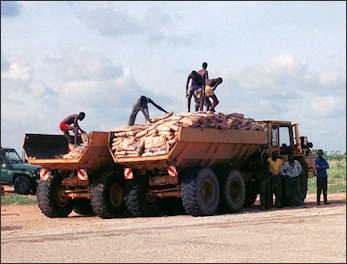

Aid in the Congo One of Sach’s biggest critics is William Easterly. He argues that Sach’s idea of mobilizing 0.7 percent of the world’s GDP to fight poverty is simply a rehashing of programs and ideas that have not worked in the past. Easterly argues that the $2.3 trillion dollars has been spent since the 1950s on poverty reduction programs has been a waste and the programs they funded failures. She says that beneficiaries of the programs often have little or nothing to show all the money spent, with Africa being worse off.

Easterly favors a more step-by-step or “piecemeal approach — is which programs are consistently evaluated for effectiveness. He wrote in the Washington Post: “Piecemeal reform...motivates specific actors to take small steps at a time then test whether that small step made poor people better off, holds accountable the agency that implemented the small steps and considers the next step.”

Easterly also favors selling aid rather than giving it out free so the that the aid has value. In his book “The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good” (Penguin Press), he describe that when malaria-fighting mosquito nets were given out free “nets are often diverted to the black market...or wind up being used as fishing nets or wedding veils” but when they are sold for $5 a piece as they were in a program in Malawi “the nationwide average of children under 5 sleeping under nets” increased “from 8 percent in 2000 to 55 percent in 2004...A follow up survey found nearly universal use of the nets by those who paid for them” while in a Zambian program that handed out nets free “70 percent of the recipients didn’t use” them.

Obstacles to Development

Why haven't Marshall-like plans in the developing world worked? Many have been undermined and failed because of corruption, red tape, and indifference, as well as a lack of infrastructure, established industries, technical expertise, established laws and educated workers. It is much easier re-starting a formally strong economy rather than starting one from scratch.

One of the major obstacles in any development project is politics. One tribesman told an aid worker working on a drought-survival program, "Even if you know what needs to be done, the powers that be won't necessarily allow you to do it...Your plan can be very good. But I doubt that anyone would ever do anything so sensible."

"Most 'program's,'" writes columnist Stephen S. Rosenfeld, "are often government programs vulnerable in their implementation to the very governmental weaknesses that contribute to the problem in the first place."

It is generally much easier to get money for a disaster that has happened than to get money to prevent one from happening. Aid agencies, a U.S. AID official told the Washington Post, are forced into walking "the fine line between crying wolf and getting supplies and preventive infrastructure into place...to deal with a potential emergency before the victims become starving children on television."

Millennium Development Goal

In September 2011, the U.N. announced the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of halving the proportion of undernourished people from 20 percent in 1990-92 to 10 percent in 2015. Shashi Tharoor wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, I was at the UN in September 2000, when world leaders met at the Millennium Summit and pledged to work together to free humanity from the “abject and dehumanizing conditions of extreme poverty,” and to “make the right to development a reality for everyone.” These pledges include commitments to improve access to education, health care, and clean water for the world’s poorest people; abolish slums; reverse environmental degradation; conquer gender inequality; and cure HIV/AIDS. [Source: Shashi Tharoor, Project Syndicate, September 14, 2010. Tharoor, a former Indian Minister of State for External Affairs and UN Under- Secretary General, is a member of India’s parliament]

Celebrities promote Millennium Development Goal

It’s an ambitious list, but its capstone is Goal 8, which calls for a “global partnership for development.” This includes four specific targets: “an open, rule-based, predictable, non-discriminatory trading and financial system”; special attention to the needs of least-developed countries; help for landlocked developing countries and small island states; and national and international measures to deal with developing countries’ debt problems.

Basically, it all boiled down to a grand bargain: while developing countries would obviously have primary responsibility for achieving the MDGs, developed countries would be obliged to finance and support their efforts for development.

Progress on the Millennium Development Goals

The United Nations agrees the world will meet the goals to halve global poverty and hunger by 2015 but is behind on other goals which cover improving child education, child mortality and maternal health; combating diseases including AIDS, and promoting gender equality and environmental sustainability. Rising incomes in emerging economic powers like China is the main reason for progress in tackling poverty there, while population growth has set back efforts in Africa and India. [Source: Lesley Wroughton and Helen Popper, Reuters, September 20, 2010]

In 2010, Shashi Tharoor wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “The UN admits that progress has been uneven, and that many of the MDGs are likely to be missed in most regions. An estimated 1.4 billion people were still living in extreme poverty in 2005, and the number is likely to be higher today, owing to the global economic crisis. The number of undernourished people has continued to grow, while progress in reducing the prevalence of hunger stalled — or even reversed — in some regions between 2000-2002 and 2005-2007. [Source: Shashi Tharoor, Project Syndicate, September 14, 2010]

About one in four children under the age of five are underweight, mainly due to lack of quality food, inadequate water, sanitation, and health services, and poor care and feeding practices. Gender equality and women’s empowerment, which are essential to overcoming poverty and disease, have made at best fitful progress, with insufficient improvement in girls’ schooling opportunities or in women’s access to political authority.

Millennium Development Goals, World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos 2008

Progress on trade has been similarly disappointing. Developed country tariffs on imports of agricultural products, textiles, and clothing — the principal exports of most developing countries — remained between 5 percent and 8 percent in 2008, just 2-3 percentage points lower than in 1998.

On the U.N. Millennium Development Goals of cutting the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation cut in half by 2015, the latest U.N. assessment on progress toward achieving the goals said that "with half the population of developing regions without sanitation, the 2015 target appears to be out of reach" but it said "the world is on track to meet the drinking water target, though much remains to be done in some regions" especially sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania. [Source: Associated Press, July 29, 2010]

Obstacles to Meeting the Millennium Development Goals

On efforts to reach Goal 8, which called for a “global partnership for development, “Shashi Tharoor wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “This hasn’t really happened. At the G-8 summit at Gleneagles and the UN World Summit in 2005, donors committed to increasing their aid by $50 billion at 2004 prices, and to double their aid to Africa from 2004 levels by 2010. But official development assistance (ODA) last year amounted to $119.6 billion, or just 0.31 percent of the developed countries’ GDP — not even half of the UN’s target of 0.7 percent of GDP. In current US dollars, ODA actually fell by more than 2 percent in 2008. [Source: Shashi Tharoor, Project Syndicate, September 14, 2010]

The time has come to reinforce Goal 8 in two fundamental ways. Developed countries must make commitments to increase both the quantity and effectiveness of aid to developing countries. Aid must help developing countries improve the welfare of their poorest populations according to their own development priorities. But donors all too often feel obliged to make their contributions “visible” to their constituencies and stakeholders, rather than prioritizing local perspectives and participation.

There are other problems with development aid. Reporting requirements are onerous and often impose huge administrative burdens on developing countries, which must devote the scarce skills of educated, English-speaking personnel to writing reports for donors rather than running programs. And donor agencies often recruit the best local talent themselves, usually at salaries that distort the labor market. In some countries, doctors find it more remunerative to work as translators for foreign-aid agencies than to treat poor patients. Meanwhile, donors’ sheer clout dilutes the accountability of developing countries’ officials and elected representatives to their own people.

Plea to Debt-Ridden Rich Countries Not to Neglect the Poor

September 2010, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon pressed debt-ridden donor countries not to cut aid to the poor despite their budgetary woes. "We should not balance budgets on the backs of the poor," Ban told 140 leaders at the start of a three-day summit to review progress Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). [Source: Lesley Wroughton and Helen Popper, Reuters, September 20, 2010]

Spanish Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, whose government cut development aid in the face of a fiscal crisis and high unemployment, said countries were grappling with difficult decisions as they try to revive economic growth. He urged the world to consider other ways to fund programs that tackle poverty, hunger and climate changes. "We need to make more effort to look for alternative financing sources ... that aren't as vulnerable as the budgets of developed countries when faced with crises like the one we're seeing today," he said.

Both he and French President Nicolas Sarkozy called for some form of financial tax to raise money to combat poverty, an idea already rejected by the International Monetary Fund and many Group of 20 major developed and developing nations. Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou said Greece's severe fiscal crisis, which prompted an IMF bailout, showed no country was immune to job losses, pandemics or the "vagaries of the financial markets."

Donors demanded more work to ensure aid is not wasted on programs that do not help the poor. Anti-poverty campaigners said donors should be held accountable for the aid they have promised and failed to deliver. British International Development Secretary Andrew Mitchell called for a plan to track progress in meeting the poverty goals over the remaining five years of the MDGs. He argued for more transparency, better donor coordination and a special focus on helping women and infants.

"We want a proper agenda for action over each of the next five years, not a load of blah-blah and big sums of money being thrown about, although big sums of money are important," he told reporters. U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) chief Rajiv Shah told Reuters the United States would press for a new development approach that highlighted economic growth, accountability and tackling corruption. With U.S. congressional elections on November 2 focusing on the economy and job losses, Washington is pressed to show Americans that their tax dollars are being put to good use.

Vietnam and Bolivia said poverty could not be beaten as long as some countries continued to benefit from skewed international economic and trading systems.Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili said aid would not work unless countries were allowed to design their own anti-poverty programs tailored to local conditions. "Of course we need more money. More money matters. But aid money will not deliver concrete results unless we pay more attention to the essential idea of local ownership."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012