WORLD POPULATION

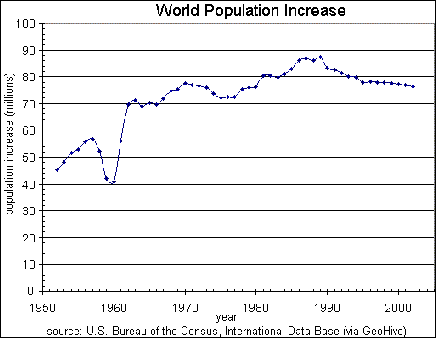

Motorbikes in Bangkok The world population is expected to rise from around 7 billion today to 9.2 billion in 2050. The world population grew by 48 percent from 1975 to 2000 compared to 64 percent between 1960 and 1975.

Population expert David Lam wrote in Los Angeles Times, “In 1960 the population hit 3 billion. Falling infant and child mortality caused population growth rates to surpass 2 percent per year in the 1960s, probably for the first time in history. At 2 percent growth, the world would double in 35 years, and that is roughly what happened — world population grew to 6 billion in 1999. World population will not come close to doubling again in 39 years. Indeed, it may never double again. Fertility has fallen rapidly, with many developing countries at or near the replacement fertility rate of 2.1. The world's population growth rate has been falling since its peak in the 1960s, and we may never get much above the 10.1 billion people projected for 2100. [Source: David Lam, Los Angeles Times, October 30, 2011, Lam is a professor of economics at the University of Michigan and president of the Population Assn. of America.]

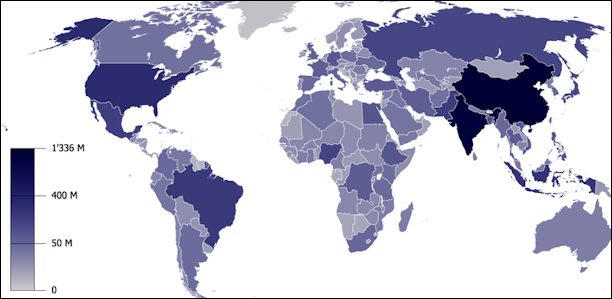

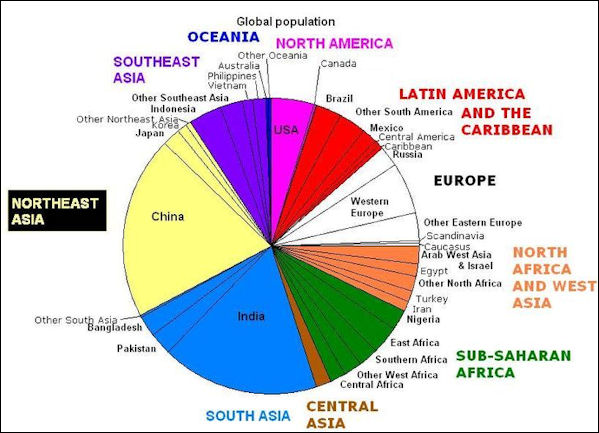

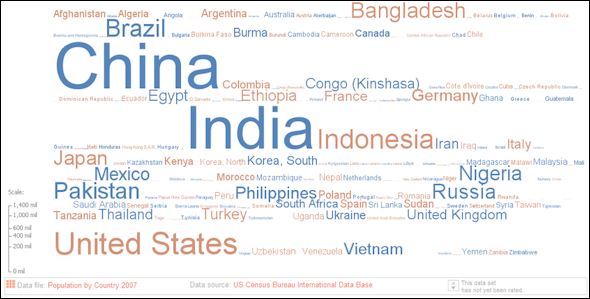

Asia accounts for 4.2 billion of the world’s population. It is projected to reach 5.2 billion in 2052 before declining slowly. The biggest rate of increase is in Africa, whose population first surpassed a billion in 2009 and is expected to add another billion by 2044. China is the world’s most populous country, with 1.35 billion, followed by India with 1.24 billion. In 2025, India will have 1.46 billion, overtaking China’s 1.39 billion. China’s population will decline to about 1.3 billion by 2050; India’s will peak at 1.7 billion by 2060. [Source: State of the World Population 2011, UN Population Fund, October 2011, AFP, October 29, 2011]

Prosperity, better education and access to contraception have slashed the global fertility rate to the point that some rich countries have to address a looming population fall. Over the past six decades, fertility has declined from a statistical average of six children per women to about 2.5 today, varying from 1.7 in the most advanced economies to 4.2 in the least developed nations. Even so, 80 million people each year are added to the world’s population. People under 25 comprise 43 per cent of the total. [Source: State of the World Population 2011, UN Population Fund, October 2011, AFP, October 29, 2011]

World Population Reach Seven Billion in 2011

The world’s population hit 7 billion people in October 2011, according to United Nations estimates. “Our record population can be viewed in many ways as a success for humanity — people are living longer, healthier lives,” said U.N. Population Fund ( UNFPA) executive director Babatunde Osotimehin.

World population increase history

At the same time, Nicholas Eberstadt wrote in the Washington Post, the marking of the milestone launched “another round of debates about “overpopulation,” the environment and whether more people means more poverty.”[Source: Nicholas Eberstadt, Washington Post November 4, 2011, Eberstadt is the Henry Wendt scholar in political economy at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of “The Poverty of the Poverty Rate”]

On whether this meant the world was overpopulated, Nicholas Eberstadt wrote: ‘Sure, 7 billion is a big number. But most serious demographers, economists and population specialists rarely use the term “overpopulation” — because there is no clear demographic definition. For instance, is Haiti, with an annual population growth rate of 1.3 percent, overpopulated? If it is, then was the United States overpopulated in 1790, when the new country was growing at more than 3 percent per year? And if population density is the correct yardstick, then Monaco, with more than 16,000 people per square kilometer, has a far greater problem than, say, Bangladesh and its 1,000 people per square kilometer.

Back in the 1970s, some scholars tried to estimate the “optimum population” for particular countries, but most gave up. There were too many uncertainties (how much food would the world produce with future technologies?) and too many value judgments (how much parkland is ideal?). Even considering resource scarcity isn’t all that helpful. During the 20th century’s population explosion — when we went from 1.6 billion people to more than 6 billion — real prices for rice, corn and wheat fell radically, and despite recent spikes, real prices for food are lower than 100 years ago. Prices, of course, are meant to reflect scarcity; by such reasoning, the world would be less overpopulated today than a century ago, not more.

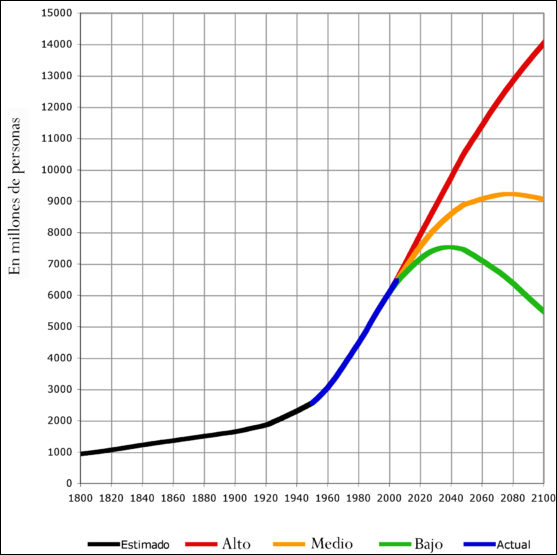

On whether the world will have 10 billion people by 2100, Eberstadt wrote No one can know how many people will be alive in 2100 because demographers have no techniques for accurately projecting our long-term population. The United Nations did predict a population of 10.1 billionin 2100 earlier this year — but that was just its “medium variant” projection; it also put out a “high variant” projection (exceeding 15 billion) and a “low variant” (6.2 billion, lower than the world’s population today).

Further complicating matters, we are seeing unprecedented declines in birth rates in some low-income countries. In just two decades, for example, total fertility in Oman is estimated to have fallen by 5.4 births per woman, from 7.9 in the late 1980s to 2.5 in recent years. And just a few years ago, the United Nations’ “medium projection variant” for Yemen in 2050 exceeded 100 million — now it is down to 62 million.

On Surviving the Population Bomb

In October 2011 after it was announced the world population reached seven billion, David Lam wrote in Los Angeles Times, “So we've just been through the fastest population growth the world will ever see. It's a good time to look back and see how the world survived it. There were gloomy predictions in the 1960s about the consequences of rapid population growth, the most famous appearing in Paul Ehrlich's 1968 book, "The Population Bomb." He wrote that "the battle to feed humanity is already lost, in the sense that we will not be able to prevent large-scale famines in the next decade." Happily, Ehrlich was wrong. World food production grew faster than population during the last 50 years. Food production per person in 2009 was 41 percent higher than in 1961. [Source: David Lam, Los Angeles Times, October 30, 2011, Lam is a professor of economics at the University of Michigan and president of the Population Assn. of America.]

No country generated more fear about overpopulation than India. But food production there has grown faster than population since the Green Revolution of the late 1960s. Food production per person in India today is 37 percent higher than in 1961, although there are 2.6 times more people. Although there are still serious problems with food distribution and malnutrition, we have done remarkably well at feeding the extra 4 billion people added since 1960. This should make us optimistic about feeding the 3 billion more to be added in the next 70 years.

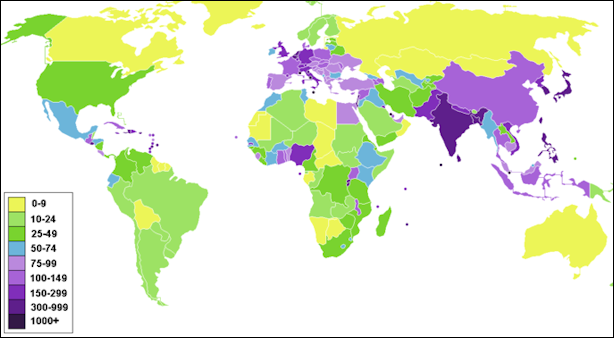

World population by country

Increased food supply is one reason that children around the world today are the healthiest ever born. An Indian baby born in 2011 has almost double the probability of surviving the first year of life as a baby born in 1960. The probability that a child will grow up in poverty has been going down. For developing countries as a whole, the percentage living below the World Bank's $1.25-per-day poverty line fell from 50 percent in 1981 to 25 percent in 2005. India's poverty rate fell from 60 percent in 1981 to 42 percent in 2005 and can be expected to keep falling.

Not all countries have done as well as India. But even in sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the poorest economic performance, poverty rates have fallen, education has increased and food production per person has been rising (albeit slowly) since the 1980s. None of this is meant to deny the enormous challenges we face. We survived the population bomb through hard work and creativity, and we will need more of it to continue to feed the world and reduce poverty. But the remarkable experience of the last 50 years teaches us that we should not be afraid to celebrate the birth of the 7-billionth child.

U.N. Report on World Population: At Least 10 billion by 2100

The world’s population is set to rise to at least 10 billion by 2100, but could top 15 billion if birthrates are just slightly higher than expected, according to a U.N. report issued at the time the world population reached the seven billion people mark. New estimates see a global human tally of 9.3 billion at 2050, an increase over earlier figures, and more than 10 billion by century’s end, the UN Population Fund said, warning demographic pressure posed mighty challenges for easing poverty and conserving the environment. [Source:AFP, October 29, 2011]

But, the reported added, “with only a small variation in fertility, particularly in the most populous countries, the total could be higher: 10.6 billion people could be living on earth by 2050 and more than 15 billion in 2100.”

World population pie chart

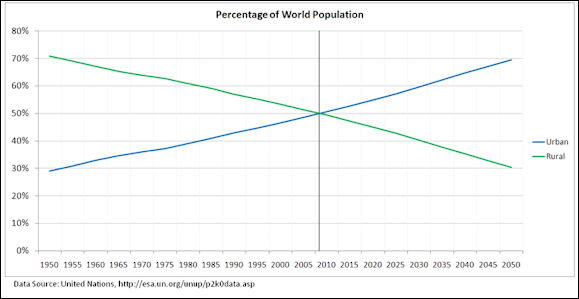

The report highlighted various challenges such as: Helping youth: Having large numbers of young adults offers many poor countries the hope of rising from poverty. Green worries: The report cites environmental problems that are already pressing and set to intensify as demand grows for food, energy and homes. City futures: The balance between rural and urban populations “has tipped irreversibly” towards cities in today’s world of seven billion and finally the issues concerning immigration and family planning.

Population Growth and Fertility Rates

A fertility rate of 2.1 children per woman is necessary to keep the population from starting to shrink. Each year around 80 million are added to the world’s population, a number roughly equivalent to the population of Germany, Vietnam or Ethiopia. People under 25 comprise 43 per cent of the world’s population. [Source: State of the World Population 2011, UN Population Fund, October 2011, AFP, October 29, 2011]

Populations have soared with the development of technology and medicine that have greatly reduced infant mortality and significantly increased the life span of the average individual. People in poor countries today in many cases are giving birth to the same number of children they always have. The only difference is that more children are living, and they are living longer. The average life expectancy rose from about 48 years in the early 1950s to about 68 in the first decade of the new millennium. Infant mortality fell by nearly two-thirds.

Around 2,000 years ago, the world’s population was around 300 million. Around 1800, it reached a billion. The second billion was notched up in 1927. The three billion mark was swiftly reached in 1959, rose to four billion in 1974, then accelerated to five billion in 1987, six billion in 1999 and seven billion in 2011.

One of the paradoxes of population control is that the overall population can continues to rise even when fertility rates drop below 2.1 children. This is because a high fertility rate in the past means a large percentage of women are at childbearing age and are having children, plus people are living longer. The main reason for the demographic surge of recent decades has been the Baby Boom of the 1950s and 1960s, which shows up in ensuing “bulges” when this generation reproduces.

World Population Growth 1800-2100

The Economist reported in 2011: “Tthe fall in fertility is already advanced in most of the world. Over 80 percent of humanity lives in countries where the fertility rate is either below three and falling, or already two or less. This is thanks not to government limits but to modernisation and individuals’ desire for small families. Whenever the state has pushed fertility down, the result has been a blight. China’s one-child policy is a violation of rights and a demographic disaster, upsetting the balance between the sexes and between generations. China has a bulge of working adults now, but will bear a heavy burden of retired people after 2050. It is a lurid example of the dangers of coercion. [Source: The Economist, October 22, 2011]

Enthusiasts for population control say they do not want coercion. They think milder policies would help to save the environment and feed the world. As the World Bank points out, global food production will have to rise by about 70 percent between now and 2050 to feed 9 billion. But if the population stays flat, food production would have to rise by only a quarter.

Young Populations and Why Poor Families Have So Many Children

Socioeconomic worries, practical concern and spiritual interests all help explain why villagers have such large families. Rural farmer have traditionally had many children because they need the labor to grow their crops and take care of chores. Poor women traditionally had many children in hope that some would survive until adulthood.

Children are also seen as insurance policies for old age. It is their responsibility to take care of their parents when they get old. Moreover, some cultures believe that parents need children to care for them in the afterlife and that people who die childless end up as tormented souls who come back and haunt relatives.

Percentage of World Population Urban-Rural

A large percentage of population in the developing world is under the age of 15. When this generation enters the labor force in the coming years, unemployment will get worse. Youth populations are large because traditional birth-and-death rate has been broken only within the last few decades. This means that many children are still being born because there are still a lot of women of child-bearing age. The main factor that determines the age rate of a population is not life span but birthrates with a decline in birthrates resulting in an aging population.

Problems Caused by Overpopulation

Despite the introduction of aggressive family planning programs in the 1950s and 60s, the population in the developing world is still rising at high rates. One study found that if fertility rates remain unchanged the population will reach 134 trillion in 300 years.

Overpopulation creates land shortages, increases the number of unemployed and underemployed, overwhelms infrastructure and aggravates deforestation and desertification and other environmental problems.

Technology often makes overpopulation problems worse. The conversion of small farms to large cash-crop agribusiness farms and industrial complexes factories, for example, ends up displacing thousands of people from the land that could be used to grow food that people could eat.

In the 19th century, Thomas Malthus wrote "the passion between the sexes is necessary and will remain" but "the power of population is infinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man."

In the 1960s, Paul Ehrlich wrote in the “Population Bomb” , that "famines of unbelievable proportions" were imminent and feeding the growing population was a "totally impossible in practice." He said that “the cancer of population growth must be cut out” or “we will breed ourselves into oblivion.” He appeared on Johnny Carson’s Tonight show 25 times to drive home the point.

.svg.png)

World population growth by region

Population and Food

Malthusian pessimists predict that population growth will eventually outstrip the food supply; optimists predict that technological advances in food production can keep pace with population increases.

In many of the world most populous areas food production has lagged behind population growth and the population has already outstripped the availability of land and water. But worldwide, improvements in agriculture have managed to keep pace with population. Even though the world population increased 105 percent between 1955 and 1995, agricultural productivity increased 124 percent in the same period. Over the past three centuries, the food supply has grown faster than demand, and the price of staples has dropped dramatically (wheat by 61 percent and corn by 58 percent).

Now one hectare land feeds about 4 people. Since populations are rising but the amount of arable land is more finite, it estimated that a hectare will need to feed 6 people to keep pace with population growth and diet changes that come with prosperity.

Today hunger is more often the result inequitable distribution of resources rather a scarcity of food and famines are the result of wars and natural disasters. When asked about whether the world can feed itself, one Chinese nutrition expert told National Geographic, "I've devoted my life to the study of food supplies, diet and nutrition. Your question goes beyond those fields. Can the Earth feed all those people? That, I'm afraid, is strictly a political question."

Somali refugee boat

Population and Poverty

Commenting on whether rapid population growth keeps poor countries poor, Nicholas Eberstadt wrote in the Washington Post, “In 1960, South Korea and Taiwan were poor countries with fast-growing populations. Over the two decades that followed, South Korea’s population surged by about 50 percent, and Taiwan’s by about 65 percent. Yet, income increased in both places, too: Between 1960 and 1980, per capita economic growth averaged 6.2 percent in South Korea and 7 percent in Taiwan.” [Source: Nicholas Eberstadt, Washington Post November 4, 2011]

Clearly, rapid population growth did not preclude an economic boom in those two Asian “tigers” — and their experience underscores that of the world as a whole. Between 1900 and 2000, as the planet’s population was exploding, per capita income grew faster than ever before, rising nearly fivefold, by the reckoning of economic historian Angus Maddison . And for much of the last century, the countries with faster economic growth tended to be the ones where population was growing most rapidly, too.

Today, the fastest population growth is found in so-called failed states, where poverty is worst. But it’s not clear that population growth is their central problem: With physical security, better policies and greater investments in health and education, there is no reason that fragile states could not enjoy sustained improvements in income.

Population, Economic Growth and the Environment

In October 2011 after it was announced the world population reached seven billion,the Economist reported: “In 1980 Julian Simon, an economist, and Paul Ehrlich, a biologist, made a bet. Mr Ehrlich, author of a bestselling book, called “The Population Bomb”, picked five metals — copper, chromium, nickel, tin and tungsten — and said their prices would rise in real terms over the following ten years. Mr Simon bet that prices would fall. The wager symbolised the dispute between Malthusians who thought a rising population would create an age of scarcity (and high prices) and those “Cornucopians”, such as Mr Simon, who thought markets would ensure plenty. [Source: The Economist, October 22, 2011]

Mr Simon won easily. Prices of all five metals fell in real terms. As the world economy boomed and population growth began to ebb in the 1990s, Malthusian pessimism retreated. [Now] it is returning. If Messrs Simon and Ehrlich had ended their bet today, instead of in 1990, Mr Ehrlich would have won. What with high food prices, environmental degradation and faltering green policies, people are again worrying that the world is overcrowded. Some want restrictions to cut population growth and forestall ecological catastrophe. Are they right?

Ivory coast Adjamemarche

Lower fertility can be good for economic growth and society. When the number of children a woman can expect to bear in her lifetime falls from high levels of three or more to a stable rate of two, a demographic change surges through the country for at least a generation. Children are scarcer, the elderly are not yet numerous, and the country has a bulge of working-age adults: the “demographic dividend”. If a country grabs this one-off chance for productivity gains and investment, economic growth can jump by as much as a third.

When Mr Simon won his bet he was able to say that rising population was not a problem: increased demand attracts investment, producing more. But this process only applies to things with a price; not if they are free, as are some of the most important global goods — a healthy atmosphere, fresh water, non-acidic oceans, furry wild animals. Perhaps, then, slower population growth would reduce the pressure on fragile environments and conserve unpriced resources?

That idea is especially attractive when other forms of rationing — a carbon tax, water pricing — are struggling. Yet the populations that are rising fastest contribute very little to climate change. The poorest half of the world produces 7 percent of carbon emissions. The richest 7 percent produces half the carbon. So the problem lies in countries like China, America and Europe, which all have stable populations. Moderating fertility in Africa might boost the economy or help stressed local environments. But it would not solve global problems.

Underpopulation and Population Growth Declines

Contraception, prosperity and changing cultural attitudes have also brought about a fall in fertility, from a statistical 6.0 children per woman to 2.5 over six decades. In more advanced economies, the average fertility rate today is about 1.7 children per woman, below the replacement level of 2.1. In the least developed countries, the rate is 4.2 births, with sub-Saharan African reporting 4.8. [Source: State of the World Population 2011, UN Population Fund, October 2011, AFP, October 29, 2011]

World population density map

In some parts of the world, families are having fewer than two children, and the population has stopped growing and begun a very slow decline. The disadvantages of this phenomena include an increased burden of elderly people that younger people have to support, an aging work force, and slower economic growth. Among the advantages are a stable work force, a smaller burden of children to support and educate, lower crime rates, less pressure on resources, less pollution and other environmental deterioration. Right now about 25 to 30 percent of the population is over the age of 65. With the low birth rate this figure is expected to rise to 40 percent by 2030.

Population growth rates in nearly all counties have declined in the last 30 years. According to a United Nations report based on 1995 data the total fertility rate for entire world was 2.8 percent and falling. The fertility rate in the developing world has been cut in half from six children per woman in 1965 to three children per woman in 1995.

Fertility rates have been declining in the developing world and middle income countries as well as in the developed world . In South Korea, the fertility rate fell from roughly five kids to two between 1965 and 1985. In Iran it fell from seven kids to two between 1984 and 2006. The fewer children a women has the more likely the are to survive.

In most places the result have been achieved without coercion. This phenomena has been attributed to massive education campaigns, more clinics, inexpensive contraception and improving the status and education of women.

In the past a lots of children may have been an insurance policy against old age and a means of working the farm but for rising middle class and working people having too many children is an impediment to getting a car or taking a family trip.

Commenting on population declines and declining growth, Nicholas Eberstadt wrote in the Washington Post, “Between the 1840s and 1960s, Ireland’s population collapsed, spiraling downward from 8.3 million to 2.9 million. Over roughly that same period, however, Ireland’s per capita gross domestic product tripled. More recently, Bulgaria and Estonia have both suffered sharp population contractions of close to 20 percent since the end of the Cold War, yet both have enjoyed sustained surges in wealth: Between 1990 and 2010 alone, Bulgaria’s per capita income (taking into account the purchasing power of the population) soared by more than 50 percent, and Estonia’s by more than 60 percent. In fact, virtually all of the former Soviet bloc countries are experiencing depopulation today, yet economic growth has been robust in this region, the global downturn notwithstanding. [Source: Nicholas Eberstadt, Washington Post November 4, 2011]

World population by country

A nation’s income depends on more than its population size or its rate of population growth. National wealth also reflects productivity, which in turn depends on technological prowess, education, health, the business and regulatory climate, and economic policies. A society in demographic decline, to be sure, can veer into economic decline, but that outcome is hardly preordained.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012