VILLAGE HOME LIFE

In poor areas, many homes have only a few pieces of furniture, and no running water. People sleep on the hard floor or on a mat and sit on the floor. How many mats, rugs or cushions there are to sit or lean on may be an expression of wealth. Water is gathered from a community well, where basins are often set up for women to do their laundry. Places that have electricity often only have it a few hours a day. Telephone service if there is any is provided by a single phone for the entire village.

Villagers often have a different sense of what is valuable than Westerners. They are sometimes willing to trade a handmade carpet worth hundreds of dollars for a refrigerator or throw out precious 200-year-old copper pots and buy aluminum pots because they are more practical. Plastic buckets, basins and carry bags are often highly desired items.

Some families make sacrifices for the possession they have. One low-income woman told the Washington Post, "Superficially you can say people are better off because of the material things they didn't used to have. But...people are very much in debt. Some families, yes, have a TV, but they don't have food to eat for the day."

"Its difficult to compare, because family life before, and the kind of development we had to keep up with, was different," she said. "During my parent's time, there was no electricity. Now families have put up with whatever is held up as this drumbeat of development, like [having] a TV or an electric fan. And if you don't have it means you are way behind civilization."

People sleeping on a hard floor or a mat find it easier to wake up at dawn than those who sleep on a comfortable bed. Homes and apartments in the affluent urban or suburban areas are furnished like homes and apartments in the West.

Poor families often keep animals such as goats, donkeys, pigs and chickens that sometimes share living spaces with people. These animals attract flies and disease-causing germs and are often a health risk to the occupants of the house. .

Village Possessions

A typical poor family spends 80 percent of its income on food and has little over for anything else. They have no stereo, TV, VCR, telephone or car. Their possessions include a machete, some toys, extra shoes, a hoe, drinking glasses, plastic food containers, a plastic washtub, plastic bucket, plastic basket, cookery, a coffee pot, thermos, 4 felt hats, towel, 30 items of clothes, sheets.

Many of their possessions are made from sticks, grass and scrap wood and metal. They include a wheelbarrow, beds, chairs, saddle bags for the donkey, pestle, mortar, pantry cabinet, wood, rope, tables, saddles, baskets and straw hats. Large palm leaves serve as umbrellas. Small leaves serve as plates. Bushes are used for drying clothes.

There isn't much furniture except for a low table, a few stools to sit on, a large drum of water and a grinding mill for corn. Beds are bamboo or wooden platforms, mats or a hammock. Food is cooked over an open fire pit or primitive stove.

Many homes have no furniture. Dirt floors are covered with rugs and people sit on foam rubber pads. There aren't any tables or chairs because the family spends most of its indoor non sleeping time sitting or lying on the floor. Affluent families have Persian carpets and long rectangular cushions.

Modern conveniences that have improved village life include solar powered lanterns, wind-up radios, solar water heaters, electricity-producing wind turbines, and fuel-efficient stoves that don't let heat escape.

Toys include hoops, push carts, tops, and marbles. Families have little money for toys and amusements so children learn to make things for themselves: small sailboats made from broken sandals and popsicle sticks; soccer balls made from wadded up plastic bags and twine; pull toys made from sardine cans or plastic bottles; and puppets and dolls are made from wood, bamboo and scraps of old clothes. Rocks are often used as toys.

Refrigerators and Televisions in Villages

Satelite dish in Laos Though many people have televisions, VCRs, satellite dishes or cable hook-ups and DVD players they often don't have refrigerators, washing machines and driers.

Refrigerators are often considered a luxury. With refrigerators people don't have to buy food everyday. But they are not practical because power supplies are often unreliable and when it is reliable it is very expensive.

About a quarter of developing world food production is lost to spoilage, . "Pot-in-pot" refrigerators devised by Nigerian teacher Mohammed Bah Abba have helped farmers to keep their produce from rotting in hot areas. The device consists of one pot placed in another. Between the pots is wet sand. When water evaporates it cools produce placed inside the inner pot.

Television in the Developing World

Televison have become common even in places with unreliable electricity or no electricity at all (they are powered by generators, batteries or car batteries). Many villagers even have access to satellite television or cable. There are also a lot of villages who have a satellite dish displayed prominently outside their house but don’t have it hooked up.

In some cases villagers make enough from selling cash crops such as coffee or cacao or livestock animals to afford a satellite dish for themselves. Often an enterprising individual in the village buys a satellite dish and runs cables from the satellite box to his neighbors televisions and charges them a fee. VCRs and DVD players are also common. DVDs and videos are often pirated.

Television watching has traditionally been something that people did communally: gathering around a single, generator-powered set in village to watch a soccer match or popular soap opera. These days many people have their own sets.

Radio and Hand-Cranked Radios in the Developing World

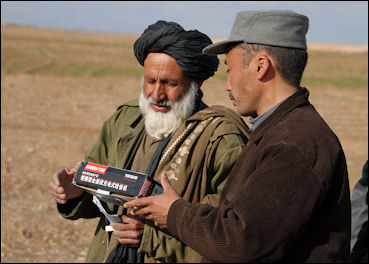

radio in Afghanistan Radio is the most widely utilized from of electronic media in the developing world. According to some estimates 80 percent of the world's population have access to radio.

With electricity being in short supply in many areas, radio is the main electronic medium for dispensing news and information. Shortwave radios, powered by batteries, solar energy, and car batteries, are the main sources of international news in places without electricity.

Many people got their news by radio listening to local-language programs produced by BBC World Service, Voice of American and the French Radio Monte Carlo. Shortwave radio listeners tune in regularly to the BBC. It is picked up in over 100 countries and is listened to by an estimated 140 million regular listeners.

The BayGen Power company in Cape Town South Africa produces a six-pound, low-fidelity, hand-cranked radio that sells for $40. Invented by British inventor Trevor Bayliss, it utilizes a spring (similar to the one used to role up seat belts) that is tightened with a hand crank and powers a generator when uncoiled. Useful in places where there is no electricity and batteries are prohibitively expensive, it operates for about 30 minutes on 20 seconds of hand cranking. The BayGen Power company also makes a hand-powered flashlight. Sony makes a waterproof radio powered by a hand crank generator. It is marketed as being useful in natural disaster and sells for $103.

Energy Sources in the Developing World

Places with little or no electricity rely on generators, candles, kerosene lamps, paraffin lanterns, firewood, batteries or car or tractor batteries. The nights in these places are very dark. You can see the stars clearly from almost anywhere because there are few lights.

Many rely on kerosene lamps as their primary source of light and cooking fuel. Kerosene is highly flammable and emits greenhouse gases. Fumes are smelly and noxious. Every year thousands of people die in fires and accident involving kerosene stoves and lamps.

For many people dung, firewood or charcoal are the main sources of energy. The poorest people use dung and agriculture waste fires. People slightly better off use wood or charcoal and those better off still have access to propane and kerosene. Those lucky enough to have electricity usually only receive it for a couple of hours in the evening or endure frequent brown-outs and power outages Gasoline is sometimes in such short supply and so expensive that is sold in small bottles.

Governments often offer subsidies and have price regulations to keep fuel prices artificially low. State-owned refineries sell at a loss or use taxpayer funds to buy imported oil. If they didn’t there is a risk of riots or revolts.

Fires, Dung and Trees

Indian girls making tea over open fire In most homes cooking is done on a metal plate placed over a wood or dung fire. Cooking is often done outside because there is a danger of fire. Kerosene, propane, oil and butter lamps are used to light a house. Candles are regarded by many as prohibitively expensive.

People who rely on cow dung for energy, collect it in the morning from their corrals or fields. Some of the dung is mixed with straw and made into a past that is used to plaster house walls. Most of the rest is flattened and broken into pieces and used as fuel. Collecting and processing dung occupies much of the time of the children and women.

Trees cut down in deforested areas are often used for fuel or charcoal. Fuel wood consumption in the developing world increased 35 percent between 1975 and 1986.

Charcoal

Charcoal is the porous, black brittle substance produced when woods or bones are partially burned. It is an impure variety of carbon, which is able to absorb large quantities of gases. Charcoal production and use creates greenhouse gases.

Charcoal is preferred to wood because it is slow burning, produces little ash, gives off relatively little smoke, produces a hot even heat ideal for cooking, and is easy to transport.

Industrial charcoal is used in making gunpowder, filtering water, curing tobacco, manufacturing glass, making silicon alloys and chrome steel. In the developing world it is mainly used for cooking and as a source of heat.

Charcoal is made by slowly burning hardwoods for three days under a blanket of wet leaves and earth. It is a dirty process. Using the traditional method, wood is placed in a pit in a pyramid-like pile and covered by the earth-leaves blanket. Holes are left at the bottom for air to enter and at the top for a chimney.

The wood burns slowly. When fully burned, the heap is covered and left to cool for two or three days. Using this method the weight of the charcoal is about 20 percent of the wood used to make it. These days charcoal is often made in special ovens. With this method the weight of the charcoal is about 30 percent of the wood used to make it.

Low-Tech Stoves

Cooking vessels Solar grills use mirrors to focus sunlight on the grill tray. The Hot Pot is a device with aluminum panels and a glass bowl that can heat food to 300 degrees F with solar energy. It sells for about $100. Solar Household subsidizes a $40 Hot Pot with cardboard reflectors. The United Nations Development Programme has given people $110 to build a solar oven from wood.

In 2009, John Bohmer, a Norwegian living in Kenya, won a $75,000 “green” prize for devising a $7 version of cardboard box oven than can disinfect water and cook food. The outside is comprised of a large box with aluminum-foil-covered flaps that can be tilted to collect heat. Another box sits inside the outside box. The inside of this box is painted black to absorb heart. Between the two boxes are newspaper, grass or sawdust that acts as insolation. A dark pot with a lid is placed in the black box. A glass or Plexiglas lid helps keep heat in. Such a devise can generate heat of 195 degrees F on June day in Washington D.C. — more than enough the kill germs in water.

Japanese organization called Soft Energy Project is involve in getting low-tech stoves to places that have been heavily deforested by people seeking firewood.

Chinese Solar Water Heaters

China is a leader in the manufacturing and sale of solar water heaters — relatively unsophisticated, mattress-size, stainless steel devices that use the sun rays to heat water and cost about $220. Used for household purposes such as showering. washing dishes and washing, the device consists of an angled row of cola-colored glass tubes that absorb heat from the sun. The most common models are filled with cold water. As the solar heater is heated, the water rises into an insulated tank where it can remain hot for days. [Source: David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, September 2009]

village solar power Models produced by Dezhou-based China Himi Solar Energy Group cost between $190 and $2,250 and work even when temperatures are below zero and the skies are filled with clouds or smog. Unlike solar panels that use expensive technology to produce electricity the solar water heaters consist of a row of sunlight-capturing glass pipes angled below an insulated water tank. Sunlight travels freely through the glass, generating heat that is trapped in a central pipe where the heat is transmitted to water. The secret to operating in cold temperature is the vacuum separating the inner tube with its energy-trapping coating from an outer tube.

In Rizhao, a seaside city in Shandong Province with 2.8 million people, 99 percent of the households use solar water heaters. The devices used there have improved so much over the years some don’t need direct sunlight and function on cloudy or smoggy days. Advanced models have electrical water heaters that switch on during frigid cold days.

As of 2009 more than 30 million homes in China had solar water heaters, accounting for two thirds of the world’s solar water heating energy and preventing more than 20 million tons of carbon dioxide from entering the atmosphere. Christopher Flavin of the Washington-based Worldwatch Institute told the Los Angeles Times, “China absolutely dominates the global market and they have done it relatively quietly and without a lot of fanfare. It’s an interesting example of their ability to take technology that was developed elsewhere and adapt it to their market on a scale no one had conceived of.”

The heating of water typically accounts for a quarter of the energy used in a building. The use of water heaters is so high in Rizhao because the local government there requires solar water heaters to be installed in all homes and subsidizes their cost. For many families that installed the devices it was the first time they ever had reliable hot water. In Dezhou, another city known for energy conservation, 90 percent of the household and streets are lit with solar-powered lights.

The solar water heater market in China is very competitive. More than 5,000 companies manufacture water heaters there. The president of Gold Giant, one of 150 manufacturers in Rishao, told the Los Angeles Times, “The market is huge but the competition is fearsome.” Another water heater maker has had success with the slogan that his water heater will “take the feathers off a chicken.” The largest in China, Himin Solar Energy Group, got a $50 million investment from Goldman Sachs. Some are looking for export market abroad. The American market, where people use an average of 400 liters of water daily, will be difficult to crack because the heaters don’t heat that much water.

LED Lamps and Solar Lanterns

Some people have no light sources and simply go to bed or sit around in the dark when the sun goes down, Others use oil lamps or candles. Oil lamps generally only illuminate an area of 50 centimeters around the light and give off fumes that can lead to bronchitis.

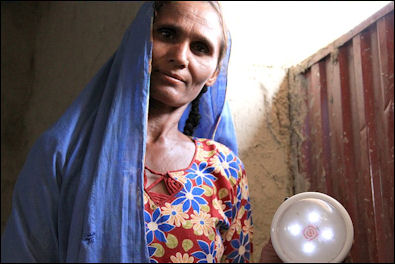

Lighting in Sindh, PakistanLow-energy, white light-emitting diodes (LED) lamps hold great promise for lighting up villages. Enough lamps to light up a whole village use less energy are needed to light up a single 100-watt bulb. NGOs are helping local entrepreneurs to sell the lights so they are the ones make money not outsiders. Villagers who have the lights no longer have to spend lots of money on kerosene and batteries.

A Japanese organization called the Gaia Initiative is active in introducing solar lanterns to villages without electricity. The lanterns can be recharged using power generated by solar panels. The system, which includes a 1.6-square -meter solar panel and 50 lanterns that can be charged with it, currently cost around $8,500 but prices will come down as the technology improves and more are mass produced.

Solar lanterns that can provide several hours of light a night cost between $66 and $112. One vendor in India that credited a solar lantern with improving sales at his vegetable stall by $6 a night told Reuters, “The vegetables look better by ths light, and it’s cheaper than kerosene and doesn’t smell. If we can use the sun to save money, why not?”

The owner of one lantern told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “I couldn’t even wash the dishes, because it became pitch-dark in the house as soon as we finished eating, So the lantern is very helpful.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012