COMMUNICATIONS IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

One Laptop per Child in Haiti In many villages there are no land-line phones and news and information has traditionally been conveyed by word of mouth. As of the mid 2000s, an estimated 30 percent of all villages worldwide still lacked basic telephone service. Where such service is available there are often long waits to get land-line phones. This situation has quickly changed in many places with the widespread introduction of cell phones.

The term the “digital divide” describes the gap between access to advanced communications in the developing world and the developed world . As of 2007, some 30 countries still relied in a single 10Mbps international connection to serve their entire populations. In wealthy countries individuals could buy their own persona 10Mbps connection at affordable prices. Access to broadband service in much of the developing world is near zero. Among those committed to reducing this divide are Microsoft, which has donated more that $3 billion in cash plus free software to developing countries.

Cell Phones

In 2008 the world reached a major milestone. That year it was estimated that 3.3 billion cell phones were in service, or roughly one for every two of the world’s 6.6 billion people. This was up from virtually zero in the mid 1980s. The figure reached around 4 billion in 2010 as around 1,000 new cell phones were hooked up every minute. Sales have been accelerating. According to market database Wireless Intelligence it took 20 years for the first billion mobile phones to sell worldwide. The second billion were sold in four years. The third in two years.

Eighty percent of the world’s population lived in range of cellular network in 2006, double the figure in 2000. Eric Smidt, a top executive at Google told the Washington Post, “Eventually there will be more cell phones used than people who can read and write. I think if you get that right, then everything else becomes superfluous.” Arthur Molella of the Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center of the Study of Invention and Innovation said the cell phone is “technology most adapted to the essence of the human species — socialiablity. It’s the ultimate tool to find each other . It’s wonderful technology for human beings.”

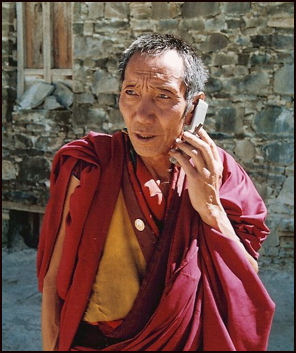

Tibetan monk with cell phone Rich Ling, of the global phone company Telmor and author a book on cell phone connectivity, told the Washington Post, “The internet is quite global. But the mobile phone is the way social cohesion is taking place. It tightens the bonds between us...Quite a bit of research shows that the tighter the group, the more they use the mobile phones. It take place in mundane ways — work, jokes, gossip. Co-ordinating a birthday for your child, arranging the gang meeting at a restaurant ...All the other electronic media — television, the Internet — there’s real questions, whether they’re fraying the social fabric. But all the research in mobile phones shows tightening of bonds within small groups.” That’s because with cell phones, “I call an individual. In the old system, I call a place and hope somebody might be there.”

There are more than 30 countries, including Italy and Israel , with more cell phones than people. “The cell phone allows us to create that local sphere” and “that is the hallmark of village life,” Ling said. Members of cell phone circles tend to “know what you’re up to, who you are, what’s in your refrigerators. That’s a way of being attached to society. It has a socializing effect.”

Cell phones were invented by AT&T’s Bell Labs. Based on advice from its consulting company, McKinsey, which estimated than only 1 percent of Americans would have cell phones in the year 2000, AT&T decided not to enter the cell phone market. The first 100 hand-held cell phones went into service in Washington D.C. in 1982. They were about the size of a walkie talkie. Coverage was limited because there were only a handful cell relay stations.

Today’s smart phones allow people to send and receive pictures and video, search websites and vote on television game shows. With Global Positioning System you can see where you are and figure out where to go. Accelerometers give you an idea of how much exercise you are getting and how many calories you are burning up. Cell phones can be used as credit cards and carry almost everything found in a wallet. Today’s iPhones have the same processing power as the North American Air Defense Command in 1965.

Cell Phones in the Developing World

According to the International Telecommunications Union, 68 percent of the world’s mobile phone subscriptions were in the developing world at the end of 2006. Transmission towers have been going up at a rapid paces as more and more countries have abandoned their government telecom services and instead offer cellular networks licenses to the highest bidding private investors, freeing the process from restrictive government regulations.

Cellular telephones are very popular in developing countries. They are a good way to get people phone service quickly, especially where the land-line systems are poor and not readily available." For many people cell phones are a status symbol and the more expensive the phone and the service the higher the status attached to them.

More than 30 African countries have more cell phone than land lines. Sara Corbett wrote in the New York Times magazine, “Unlike fixed line phone networks, which are expensive to build and maintain and require customers to have both a permanent address and the ability to pay a monthly bill, or a personal computers, which are not just costly but demand literacy as well, the cell phone is more egalitarian, at least to a point.”

Still there are limitations. Network towers are not particularly cost-effective in remote areas, where diesel fuel is the main power source. Power itself is a problem in many villages that still don’t have electricity. Motorola and others are experimenting with wind- and solar-based charging stations but they don’t generate much energy on cloudy, windless days.

Cell Phones Users in the Developing World

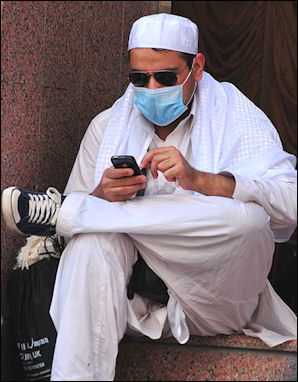

Hajj pilgrim with cell phone In a 2006 study entitled “The Next Four Billion”, the World Resource Institute reported that even very poor families invested a significant chunk of their limited income on information-communication technology (ICT), usually cell phones paid for with prepaid cards. The study also found that when income increased from say $1 a day to $4 a day, spending went up in the ICT area faster than any other category, including health, education and housing. Al Hammnd, the chief author the study, told the New York Times magazine, “What people are voting for with their pocketbooks, as soon as they have more money and even before their basic needs are met...is telecommunication.”

In many parts of the developing world you can find homes without toilets, without even out houses, but the residents have cell phones. Kevin Kelly of Wired magazine told the Washington Post he stayed at a house in Tibet as large as his own in the United States: “They could build shelters. But they didn’t build toilets...Went in the barnyard like their livestock. But many have better cell phone coverage than we do at home. Communications, not cleanliness, is next to godliness.”

Jan Chipchase is “human-behavior researcher” with Nokia whose primary job is to figure out how to make cell phones useful to people in the developing world. He has worked with designers on making phones that will operate even after being doused in monsoon rains and falling off the back of a motorbike. He also worked on phones that will work as a flashlight when the lights go out and can be charged from a car battery. In his travels around the globe Chipchase has found that Muslim users want phones that indicate the direction of Mecca; users in war-ravaged areas want ones with mine detectors; and women want ones that can ferret out cheating boyfriends. His study of how phones are shared by illiterate families and villages led Nokia to design phones with easy-to-understand icons rather than letters and multiple address books that allow many people to use the same phone. [Source: Sara Corbett, New York Times magazine, April 13, 2008]

Most people belong to a certain cell phone service because their friends and relatives do. Communication is better and simpler with people who belong to the same system. Some people have a couple handsets and belong to more than one service and use the service that works best in a particular area when they are there.

Cell Phones Uses in the Developing World

Cell phone users use their cell phones to check market prices for agricultural products and store cash via electronic money. In many places access to these services has freed villagers from profit-taking middlemen and allowed them to get more money for the products. There are cases in which poor farmers benefit from the system without even owning cell phones by joining other farmers represented by an agent with a cell phone who look for deals in the farmer’s interest.

One of the greatest benefits of cell phones in the developing world is simply to find out if people are where they are supposed to be. For example if a villager sets off with a sick child for a three hour journey from her village to the nearest town with a clinic she want to make sure the doctor will be there.

Among those who have benefitted from cell phones have been house cleaners who have used their phones to get new customers and easy-to-contact porters who used hang out at a given location all the time because there was no other way employers could contact them but now can be reached anywhere. Rickshaw drivers, prostitutes, shopkeepers and laborers have all been able to profit from similar arrangements.

A study of fisherman in Kerala, India by Harvard economics professor Robert Jensen found that fishermen who used cell phones to find out news of the best deals before they came ashore increased their income by 8 percent while consumer prices went down by 4 percent. A 2005 London Business School study calculated that an addition 10 mobile phones per 100 people, boosted GDP by 0.5 percent.

Text messaging, or S.M.S. (short message service), are especially handy because they are so cheap. In some places health workers remind people with tuberculosis to take their medication and people can ask questions about sensitive topics such as breast cancer and AIDS. A number of cell phone banking systems, including GCash in the Philippines and Wizzit in South Africa, have been set up for cell phones. In Uganda, a system called “sentai” uses prepaid cards to transfer money. Under this system a user buys a card and then enters the code not into his phone but rather into the phone of an agent in the place the money is transferred to and the agent takes a small commission and gives the cash to the person designated by the user who bought the prepaid card.

Grameen Phones

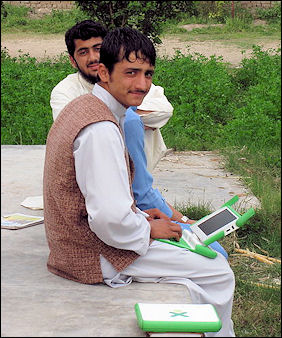

$100 laptop in Afghanistan Cell phones were one of the moving forces behind the Nobel-prize-winning Grameen micro-financing system. In Bangladesh, Grameenphone covers 98 percent of the country and serves the majority of the country’s cell phone users. Phones developed for the developing world sell for as little as $20 a piece.

GrameenPhone Ltd was started in 1996 in Bangladesh with the help of a Norwegian telephone company after a Bangladeshi expat living in the U.S. named Iqbal Quadir posed a question to Grameen founder Muhammed Yunus: if you can give a micro-loan to a woman to buy a cow why can’t you give her one to invest in a phone. The company focused on two sectors: 1) urban customers and 2) village phone schemes in which people — mostly village women — took out small loans to purchase cell phones and they in turn sold time on cell phones to others.

GrameenPhone Ltd made a pre-tax profit of $27 million after only five years in business and attracted nearly $200 million in investment as of 2002. By the mid 2000s, the system employed 250,000 “phones ladies,”, who used microcredit loans to buy specially-designed cell phone kits costing about $150 outfit with special long-lasting batteries. The ladies often operate in villages as phone operators who charge a small commission to make and receive calls. By the late 2000s, GrameemPhone was pulling in annual revenues of $1 billion a year.

Similar systems have been set up in Indonesia, Rwanda, Uganda, Cameroon and other countries. Quadir, who is now at MIT, told the New York Times magazine, “Poor countries are poor because they are wasting their resources. One resource is time, another is opportunity. Lets say you can walk over to five people who live in your immediate vicinity, that’s one thing. But if you’re connected to one million people, your possibilities are endless.”

Computers and the Internet in the Developing World

The use of the Internet has created sort of “local tribe” by allowing people in any part of the world to see what is popular anywhere else.

Internet and wireless communications can help villagers do things like: 1) keep an eye on crop prices so they don't get ripped of by middlemen and know the best time to take their crops to market; 2) get quick help after natural disasters; 3) seek help for treating sick livestock; 4) get the latest weather forecasts; and 5) gain access to health and educational materials.

Internet cafes are common in places frequented by tourists. Internet users are often frustrated by power failures and overloaded telephone lines.

One of the biggest problems with using computers in villages without electricity is finding a electricity source. Car batteries are a common source. Some people use a device with jumper cables attached to a car cigarette lighter.

Broadband Internet can be provided to remote areas using base stations with microwave transmitters that can reach places within a radius of two kilometers. Some remote villages are connected with the Internet using computers and solar-powered wireless systems provided by Iveneo, a San-Francisco-based non-profit group. Designed to be easy to setup and maintain, the system consists of a regional hub and wireless relay stations — some attached to trees — that can connect computer that as far as four miles apart. The cost of the system, including the solar panels and relay stations, is around $2000.

In the developing world Linux is being pushed as a cheap alternative to Windows and other Microsoft software.

Some entrepreneurs in the United States and other developed countries with connections in the developing world have made large profits by buying up old computers for as little as $10 a piece and sending them to developing countries where the computers can be sold for around $150 a piece.

$100 Laptop

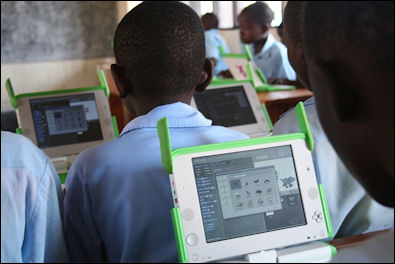

One laptop per child at Kagugu

Primary School, Kigali Rwanda In 2007 the “One Laptop per Child” program of the Media Lab of Massachusetts Institute Technology unveiled their $100 laptop. It initially cost about $188 per unit but the cost was expected to come down to $100 per unit when production reached the 50 million mark.

The main force behind the project was Nicholas Negroponte, the former head of MIT’s Media Lab. His hope was to put computers in the hands of millions of schoolchildren in the developing world. Endorsed by the United Nations and unveiled at the 2006 World Economic Forum in Davos, the devise is about the size of a textbook, has wireless capabilities and can operate in places without electricity. Critics dismiss it as a “gadget” not a computer and say it has a limited range of programs and capabilities.

The “$100 laptops” are lime green and white and constructed for a child to use. They have a keyboard that can be switched to different languages, a digital video camera, wireless connectivity to a variety of systems, and Linux open-source operating software tailored for remote regions. The computer also comes with a stripped-down browser, simple world processor, a number of learning programs and Google’s g-mail e-mail service.

The biggest obstacle to overcome pricewise was the screen, which alone costs more than $100. Chief designer Mary Lou Jepsen, a former chip designer at Intel, figured out how to reduce the display cost to $40 and reduce the power it needed. The screen is designed to last for five years. When it wears out it can be replaced as easily as a battery in a flashlight.

The $100 laptop operates on just two watts of power compared with 25 to 45 watts used by a conventional laptop. The original plan called for a hand crank to charge the battery. But this was replaced with a string pulley system, likened to a “salad spinner.” Pulling the string for a minute generates 10 minutes of electricity. The display switches from color to black and white for viewing in direct sunlight — a feature unavailable in laptops 10 times more expensive. There is no is no hard disc. It uses a solid-state memory which has no moving parts.

The $100 laptops are manufactured by Taiwan-based Quanta Computer Co. with chips supplied by AMD. The initial run was distributed to eight countries: Brazil, Uruguay, Libya, Rwanda, Pakistan, Thailand, Ethiopia, and the West Bank and was later distributed more widely to places like Indonesia. The “One Laptop Per Child” program had hoped for 3 million orders to get the ball rolling but orders were far below that.

Not everyone has been so pleased with the project. Even at $100 to $200 some feel they are still too expensive for many people in developing countries and the financial strain of possession can be a burden. Some think the money could be better spent on improving health care, schools and agriculture. Others wonder whether the laptops are suited for the education needs of impoverished countries. Other still said they would end being resold on the illegal market by cash-strapped families. Bill Gates questioned whether the concept is “just taking what we do in the rich world and subsidizing its use for the developing world.” Intel has developed a $400 alternative computer and software that is teacher-based rather than student-based as is the case with the $100 laptop.

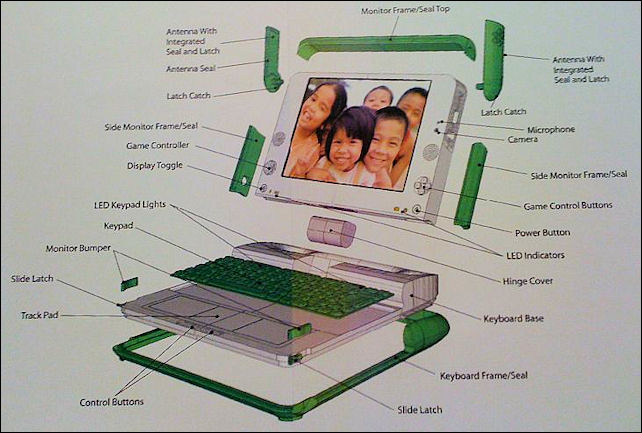

Anatomy of the $100 One Laptop per Child

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012