ANCIENT ROMAN JUSTICE SYSTEM

Trial of Jesus before the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate

The Roman judicial system distinguished laws from facts. There were indictments, jury trails, prosecutors, defense attorneys and both softhearted and unforgiving judges. Magistrates in Rome were originally called censors. Traditional Roman law was systemized and interpreted by local jurists and then supplanted by vast tax-collecting bureaucracies in the A.D. 3rd and 4th century. The legal rights of women, children and slaves were strengthened around this time. [Source: World Almanac]

In most civil and criminal cases, a magistrate defined the dispute, cited the law and referred the problem to a judex, a reputable person in the community. The judex, along with some advisors, listened to the arguments of the attorneys, weighed the evidence and pronounced the sentence. Originally major crimes against the state tried before centuriate assembly, but by late Republic (after Sulla) most cases prosecuted before one of the quaestiones perpetuae ("standing jury courts"), each with a specific jurisdiction, e.g., treason (maiestas), electoral corruption (ambitus), extortion in the provinces (repetundae), embezzlement of public funds, murder and poisoning, forgery, violence (vis), etc. Juries were large (c. 50-75 members), composed of senators and (after the tribunate of C. Gracchus in 122) knights, and were empanelled from an annual list of eligible jurors (briefly restricted to the senate again by Sulla).

Paul Halsall of Fordham University wrote: “Roman law developed as a mixture of laws, senatorial consults, imperial decrees, case law, and opinions issued by jurists. One of the most long lasting of Justinian's actions was the gathering of these materials in the A.D. 530s into a single collection, later known as the Corpus Iuris Civilis (Code of Civil Law). [Source: Medieval Sourcebook]

In the Aeneid Virgil wrote: But you, Romans, remember your great arts; / To govern the peoples with authority." To establish peace under the rule of law." To conquer the mighty, and show them/ mercy once they are conquered.” Not all Romans were enamored with the infallibility of laws. The historian Tacitus noted, "The worse the state, the more laws it has." And Even though the Romans had an impressive set of laws, Roman emperors could kill whomever they pleased (although most tried to be good citizens) and slaves were bought and sold for less than the price of a good horse.

Inscriptions from Pompeii;“A copper pot has been taken from this shop. Whoever brings it back will receive 65 sesterces. If any one shall hand over the thief he will be rewarded.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

ROMAN LAW: TYPES, CODES, ORGANIZATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PUNISHMENTS IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

DEVELOPMENT OF ROMAN LAW europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN LAWS ON MARRIAGE, PROSTITUTION, FORNICATION, DEBAUCHERY AND ADULTERY factsanddetails.com ;

CRUCIFIXION: HISTORY, EVIDENCE OF IT AND HOW IT WAS DONE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Fatal Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum: Murder in Ancient Rome”

by Emma Southon (2022) Amazon.com

“Policing the Roman Empire: Soldiers, Administration, and Public Order” (Reprint Edition) by Christopher J. Fuhrmann (2011) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Roman Law” by Barry Nicholas, Ernest Metzger Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Roman Law and Society” (Reprint Edition) by Paul J du Plessis. Clifford Ando, Kaius Tuori Amazon.com;

“Roman Law in Context” by David Johnston (2022) Amazon.com;

“Law and Empire in Late Antiquity” by Jill Harries (2001) Amazon.com;

“Human Rights in Ancient Rome” by Richard Bauman Amazon.com;

“The Digest of Roman Law: Theft, Rapine, Damage and Insult (Penguin Classics) by Justinian and C. F. Kolbert (1979) Amazon.com;

“Family and Familia in Roman Law and Life” by Jane F. Gardner (1998) Amazon.com;

“A Casebook on Roman Family Law” by Bruce W. Frier , Thomas A. J. McGinn, et al. | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Law, Language, and Empire in the Roman Tradition” by Clifford Ando (2011) Amazon.com;

“Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament” by A. N. Sherwin-White (1961) Amazon.com;

“Roman Scandal: A Brief History of Murder, Adultery, Rape, Slavery, Animal Cruelty, Torture, Plunder, and Religious Persecution in the Ancient Empire of Rome” by Frank H Wallis (2016) Amazon.com;

“Violence in Roman Egypt: A Study in Legal Interpretation” (2013) Amazon.com;

“Invisible Romans: Prostitutes, Outlaws, Slaves, Gladiators, Ordinary Men and Women ... the Romans that History Forgot” by Robert C Knapp (2011) Amazon.com

“Bandits in the Roman Empire: Myth and Reality” by Thomas Grunewald and John Drinkwater | Jul 31, 2004 (2004) Amazon.com

“Prison, Punishment and Penance in Late Antiquity” by Julia Hillner (2015) Amazon.com;

How the Justice System Worked in Ancient Rome

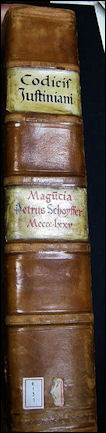

Codex JustinianEdward Gibbon wrote in the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”:“The free citizens of Athens and Rome enjoyed, in all criminal cases, the invaluable privilege of being tried by their country. The administration of justice is the most ancient office of a prince: it was exercised by the Roman kings, and abused by Tarquin; who alone, without law or council, pronounced his arbitrary judgments. The first consuls succeeded to this regal prerogative; but the sacred right of appeal soon abolished the jurisdiction of the magistrates, and all public causes were decided by the supreme tribunal of the people. But a wild democracy, superior to the forms, too often disdains the essential principles, of justice: the pride of despotism was envenomed by plebeian envy, and the heroes of Athens might sometimes applaud the happiness of the Persian, whose fate depended on the caprice of a single tyrant. Some salutary restraints, imposed by the people or their own passions, were at once the cause and effect of the gravity and temperance of the Romans. [Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part VII,“Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

The right of accusation was confined to the magistrates. A vote of the thirty five tribes could inflict a fine; but the cognizance of all capital crimes was reserved by a fundamental law to the assembly of the centuries, in which the weight of influence and property was sure to preponderate. Repeated proclamations and adjournments were interposed, to allow time for prejudice and resentment to subside: the whole proceeding might be annulled by a seasonable omen, or the opposition of a tribune; and such popular trials were commonly less formidable to innocence than they were favorable to guilt. But this union of the judicial and legislative powers left it doubtful whether the accused party was pardoned or acquitted; and, in the defence of an illustrious client, the orators of Rome and Athens address their arguments to the policy and benevolence, as well as to the justice, of their sovereign..

The task of convening the citizens for the trial of each offender became more difficult, as the citizens and the offenders continually multiplied; and the ready expedient was adopted of delegating the jurisdiction of the people to the ordinary magistrates, or to extraordinary inquisitors. In the first ages these questions were rare and occasional. In the beginning of the seventh century of Rome they were made perpetual: four praetors were annually empowered to sit in judgment on the state offences of treason, extortion, peculation, and bribery; and Sylla added new praetors and new questions for those crimes which more directly injure the safety of individuals. By these inquisitors the trial was prepared and directed; but they could only pronounce the sentence of the majority of judges, who with some truth, and more prejudice, have been compared to the English juries. To discharge this important, though burdensome office, an annual list of ancient and respectable citizens was formed by the praetor.

After many constitutional struggles, they were chosen in equal numbers from the senate, the equestrian order, and the people; four hundred and fifty were appointed for single questions; and the various rolls or decuries of judges must have contained the names of some thousand Romans, who represented the judicial authority of the state. In each particular cause, a sufficient number was drawn from the urn; their integrity was guarded by an oath; the mode of ballot secured their independence; the suspicion of partiality was removed by the mutual challenges of the accuser and defendant; and the judges of Milo, by the retrenchment of fifteen on each side, were reduced to fifty-one voices or tablets, of acquittal, of condemnation, or of favorable doubt.

In his civil jurisdiction, the praetor of the city was truly a judge, and almost a legislator; but, as soon as he had prescribed the action of law, he often referred to a delegate the determination of the fact. With the increase of legal proceedings, the tribunal of the centumvirs, in which he presided, acquired more weight and reputation. But whether he acted alone, or with the advice of his council, the most absolute powers might be trusted to a magistrate who was annually chosen by the votes of the people. The rules and precautions of freedom have required some explanation; the order of despotism is simple and inanimate. Before the age of Justinian, or perhaps of Diocletian, the decuries of Roman judges had sunk to an empty title: the humble advice of the assessors might be accepted or despised; and in each tribunal the civil and criminal jurisdiction was administered by a single magistrate, who was raised and disgraced by the will of the emperor.

Crowded Courtrooms and Roman Passion for Litigation

Romans, jurists and pettifoggers, like the Normans of France, fell an easy prey to their passion for litigation. This mania is already discernible in the astute law speeches of Cicero. It was disastrous that it got the Urbs in its grip just at a time when the Caesars had prescribed political discussion. From the reign of one emperor to another, litigation was a rising tide which nothing could stem, throwing on the public courts more work than men could master. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

To mitigate the congestion of the courts Augustus, as early as the year 2 B.C., was obliged to resign to their use the forum he had built and which bears his name. Seventyfive years later congestion had recurred and Vespasian wondered how to struggle with the flood of suits so numerous that "the life of the advocates could scarce suffice" to deal with them. In the Rome of the opening second century the sound of lawsuits echoed throughout the Forum, round the tribunal of the praetor urbanus by the Puteal Libonis, and round the tribunal of the praetor peregrinus between the Puteal of Curtius and the enclosure of Marsyas; in the Basilica lulia where the centumviri assembled; and justice thundered simultaneously from the Forum of Augustus, where the praejectus urbi exercised his jurisdiction, from the barracks of the Castra Praetoria where the praejectus praetorio issued his decrees, from the Curia where the senators indicted those of their peers who had aroused distrust or displeasure, and from the Palatine where the emperor himself received the appeals of the universe in the semicircle of his private basilica, which the centuries have spared.

During the 230 days of the year open for civil cases and the 365 days open for criminal prosecutions, the Urbs was consumed by a fever of litigation which attacked not only lawyers, plaintiffs, defendants, and accused, but the crowd of the curious whose appetite for scandal or taste for legal eloquence held them immobile and spellbound hour after hour in the neighbourhood of the tribunals.

Roman Court Case Proceedings

A valuable hint of Martial's teaches us that on the dies fasti consecrated to civil suits the ordinary tribunals sat without a break from dawn to the end of the fourth hour. At first sight this would seem to limit the hearings to three of our hours in winter and not more than five hours at a stretch in summer. But when we look into the question it is clear that the text does not exclude the possibility of any adjournment, and other testimony compels us to believe that the session was resumed after an interval. In the Twelve Tables it is already laid down that a case which had been taken up before noon might be continued, if both parties were present, until sunset. In Martial's day it was not unusual for an advocate on one side to claim and obtain from the judges "six clepsydrae' for himself alone. We may fairly deduce from a passage of Pliny the Younger that these clepsydrae, the regularity of whose time-keeping indicates their close relation to the equinoctial time-table, took twenty minutes of our time to run out; 0hence the claim was for a period of up to two hours. If it was the custom for one advocate to take up in winter almost the ( whole of one session, it is reasonable to suppose that at least one other session for the reply and the hearing of witnesses must have been necessary to complete the case. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

There were advocates, moreover, who protested the time limit of six clepsydrae. Martial has pilloried one of these windbags in an epigram: Seven water-clocks' allowance you asked for in loud tones, Caecilianus, and the judge unwillingly granted them. But you speak much and long, and with back-tilted head, swill tepid water out of glass flasks. That you may once for all sate your oratory and your thirst, we beg you, Caecilianus, now to drink out of the water-clock! If this jesting suggestion had been adopted, twenty minutes would have been subtracted from the two hours and a half rashly granted by the judge to this insatiable talker. But they were granted only in the poet's imagination; on the other hand, if the advocate on the other side had demanded the same fine, the case which Martial cited or invented would have lasted at least five of our hours, whether interrupted or not by an adjournment.

Image of Paul in a Roman

Christian catacombThe hearings were not easy or proper. They exhausted everybody: pleaders and witnesses, judges and advocates, not excepting the spectators. Let us attend for a moment a sitting of the centumviri who exercise their jurisdiction in the Basilica lulia, their chosen domicile. Leaving the Via Sacra, which flanks the building planned and erected by Julius Caesar and reconstructed by Augustus, we mount the seven steps leading to the marble portico which framed it. Then two further steps take us into the huge hall, divided into three naves by thirty-six brick columns faced with marble. The central nave, which was also the widest, measured eighteen meters by eighty-two. The tribunes on the first story which dominated the nave and the side-aisles that flanked it accommodated the male and female spectators who had not been fortunate enough to find places closer to the parties and in the more immediate neighbourhood of "the court."

The centumviri (judges) who composed the court were not 100 in number as their name might seem to imply, but 180, divided into four distinct "chambers." They took their seats either in separate sections or all four together, according to the nature of the cases which were brought before them. In the latter case the praetor hastarius in person presided, on an improvised dais, with his ninety assessors seated on either side of his curule chair. On benches at their feet sat the parties to the suit, their sureties, their defenders, and tljeir friends. These formed the corona, or, as we might call it, the "dress circle." Farther off stood the general public. When the four chambers worked separately each had forty-five assessors with a decemvir as president, and the same arrangement was repeated four times, each chamber in session divided off from its neighbour by screens or curtains.

In either case, magistrates and the public were closely packed and the debates took place in a stifling atmosphere. To complete the discomfort, the acoustics of the hall were deplorable, forcing the advocates to strain their voices, the judges their attention, and the public their patience. It frequently happened that the thunder of one of the defending counsel filled the vast hall arid drowned the controversies in the other chambers. In one notorious instance Galerius Tracalus (who had been consul in 68 A.D.), whose voice was extraordinarily powerful, was greeted with the public applause of all four chambers, three of which could not see him and ought not to have heard him. Matters were made worse and the noise increased by the enthusiasm of "a low rout of claqueurs," whom shameless advocates, following the example of Larcius Licinus, were in the habit of dragging round after them to the hearing of any case they hoped to win, as much to impress the jury as to enhance their own reputation. In vain Pliny the Younger protested against this practice.

Vituperatio

Rebecca Mead wrote in The New Yorker: Descriptions of Nero as unhinged and licentious belong to a rhetorical tradition of personal attack that flourished in the Roman courtroom. Thorsten Opper, a curator in the Greek and Roman division of the British Museum, told me, “They had a term for it —vituperatio, or ‘vituperation,’ which meant that you could say anything about your opponent. [Source: Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker, June 7, 2021]

You can really invent all manner of things just to malign that character. And that is exactly the kind of language and stereotypes we find in the source accounts.” The scholar Kirk Freudenburg, writing in “The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Nero” (2017), argues that the lurid account of the collapsing ship — Nero is said to have sent Agrippina off with a grand display of affection, only to have his plot foiled when she swam to safety — “begs to be taken as apocryphal, a contraption of the historians’ own clever design.” Cassius Dio’s history of ancient Rome suggests that Nero was inspired to build a trick vessel after seeing a play in which a prop boat suddenly opened up, but Opper argues that the historian himself likely borrowed the idea from the play.

Similarly, when Tacitus writes that Agrippina’s final gesture was to offer her womb up to an assassin’s blade, his words mirror a passage from Seneca’s “Oedipus” in which Jocasta seeks to be stabbed in the womb “which bore my husband and my sons.” Seneca wrote the play around the time of Nero’s rule, and it’s possible that his retelling of the mythic story was inspired by the actual manner of Agrippina’s death. But it’s more probable that Seneca engaged in a dramatic invention, and that, as Opper suggests, it colored Tacitus’ later account of how Agrippina died.

Ancient Roman Lawyers

tombstone of a lawyer and son in Aquincum

Rome is considered the home of the first bona-fide professional lawyers (men who argued cases for clients before magistrates as opposed to clients representing themselves). Lawyer-like speech writers in ancient Greece helped clients prepare arguments but did not argue their cases. In Rome there were juris prudentes (men wise in law), who analyzed and came up with laws, and advocati (men summoned to one's side) and causidici (speakers of cases), who, beginning around the 2nd century B.C., began arguing the cases themselves for their clients.

Eventually a lawyer class evolved that performed many of the services associated with modern lawyering. The most sought-after lawyers wore immaculate togas and were supported by assistants paid huge fees. By charging huge fees, lawyers made enough to afford luxurious villas in the countryside and elaborate mansions (with large waiting rooms for customers) in Rome.

Closely connected with the political career then, as now, was that of the law, at all periods the obvious way to prominence and political success, and the only way to such advancement for persons without family influence. There were no conditions imposed for practicing in the courts. Anyone could bring suit against anyone else on any charge that he pleased, and it was no uncommon thing for a young politician to use this license for the purpose of gaining prominence, even when he knew there were no grounds for the charges he brought. On the other hand, the lawyer had been forbidden by law to accept pay for his services. In olden times the client had of his right gone to his patron for legal advice; the lawyer of later times was theoretically at the service of all who applied to him. Men of the highest character made it a point of honor to put their technical knowledge at the disposal of their fellow citizens. At the same time the statutes against fees were easily evaded. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Grateful clients could not be prevented from making valuable presents, and it was a very common thing for generous legacies to be left to successful advocates. Cicero had no other source of addition to his income, so far as we know, but while he was never a rich man he owned a house on the Palatine and half a dozen countryseats, lived well, and spent money lavishly on works of art that appealed to his tastes, and on books. Finally the statutes against fees came to be so generally disregarded that the Emperor Claudius fixed the fees that might be asked. Corrupt judges (praetores) could find other sources of income then as now, of course, but we hear more of this in relation to the jurors (iudices) than in relation to the judges, probably because with a province before him the praetor did not think it worth his while to stoop to petty bribe-taking. |+|

Criticism of Ancient Roman Lawyers

Juvenal

"It's the stylish clothes that sells the lawyer," wrote Juvenal. "No one would give even Cicero a case if he didn't wear a ring gleaming with an oversize diamond. The first thing a client looks for is whether you have behind you eight flunkies, ten hangers-on and a sedan chair and, in front of you, a crowd of the well-dressed...Legal eloquence doesn't often turn up in rags."

At the bottom of the ladder, where ancient versions of ambulance chasers, who took whatever cases they could get and accepted any fees that were available, which according to Juvenal could be "a measly chunk of pork, a pot of fish fry, the overage onions they issue as slave's rations and five jugs of rotgut wine." "The most salable item in the public market is a lawyers' crookedness," wrote the historian Tacitus, "Pretend you purposely murdered your mother; they'll promise their extensive special divinings in the law will get you off if they think you have money."

Martial wrote: "With a judge to pay off and a lawyer to pay," Settle the debt is my advise; much cheaper that way." One Roman satirist wrote: "What does a man need to be a lawyer? Cheating, lying, brass, shouting and shoving." Martial also wrote: I took your case: two thousand was the fee." The cash you've sent amount to one, I see/ Now why is that? I was no good, you say?/ What's more, the verdict went the other way?/ With a case like yours, instead of giving me trouble/ For my blushes alone, you should have paid me double.

Examples of Roman Court Cases

When the emperor was obliged to summon before him the cases over which he had direct jurisdiction or those which had been appealed from the provinces, he was as much a victim of overwork as the ordinary judges. We get light on this from the session in which Pliny took part during one of the emporer's country visits to his Centumcellae villa. It lasted only three days. The three cases on the list were of no great importance. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The first was an unfounded accusation brought by jealous slanderers against a young Ephesian, Claudius Ariston, "a nobleman of great munificence and unambitious popularity," who was honorably acquitted. The next day Gallitta was tried on a charge of adultery. Her husband, a military tribune, was on the point of standing for office when she disgraced both him and herself by an intrigue with a centurion. The third day was devoted to an inquiry "concerning the much-discussed will of lulius Tiro, part of which was plainly genuine, while the other part was said to be forged." Though Trajan would call and hear only one case a day, it nevertheless wasted the greater part of his time. The probate case in particular gave him a great deal of trouble. The authenticity of the codicils was challenged by Eurythmus, the emperor's freedman and one of his procurators in Dacia. The heirs, mistrusting the local courts, wrote a joint letter to the emperor petitioning him to reserve, the case to his own hearing.

After this request had been granted, however, some of the heirs pretended to hesitate out of respect for the fact that Eurythmus was the emperor's own freedman, and it was only on Trajan's formal invitation that two of them appeared at the bar to lodge accusations in their turn. Eurythmus asked leave to speak to prove his charges. The two heirs who had received permission to state their case refused to take the opportunity of doing so, pleading that loyalty to their co-heirs debarred them from representing the interests of all when only two were present. Delighted by these manoeuvres and counter-manoeuvres, counsel played hide-andseek to their hearts' content amid the jungle of legal procedure. Again and again the emperor recalled them to the point at issue, which he was determined not to lose sight of. Finally, worn out by their chicanery, he turned at last to his own counsel and begged him to put an end to their cavilling, after which he declared the session closed and invited his assessors to the delightful distractions (iucundissimae remissiones) which he had prepared for them, but which he could not offer them before the dinner hour.

Arrest and Trial of Jesus

The arrest and trial of Jesus Christ seem to have taken place about two decades after Augustus's death. According to the BBC: “No trial or execution in history has had such a momentous outcome as that of Jesus in Roman-occupied Jerusalem, 2000 years ago. But was it an execution or a judicial murder; and who was responsible? The story begins when the Galilean rebel Jesus rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, deliberately fulfilling a prophecy in the Hebrew Bible about the coming of the Messiah. He's mobbed by an adoring crowd. [Source: BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

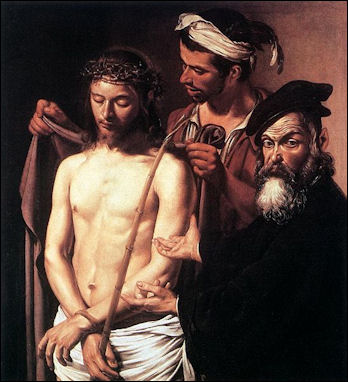

Caravaggio painting of Jesus as a prisoner“The next day Jesus raids the Temple, the heart of the Jewish religion, and attacks money-changers for defiling a holy place. The leaders of the Jewish establishment realise that he threatens their power, and so do the Romans, who fear that Jesus has the charisma to lead a guerrilla uprising against Imperial Rome. |::|

“Jesus is arrested in the Garden of Gethsemane, tried by Caiaphas and then by the Roman Governor. He's sentenced to death and executed. Caiaphas Caiaphas had a privileged position Caiaphas was a supreme political operator and one of the most influential men in Jerusalem. He'd already survived 18 years as High Priest of the Temple (most High Priests only lasted 4), and had built a strong alliance with the occupying Roman power. Caiaphas knew everybody who mattered. He was the de-facto ruler of the worldwide Jewish community at that time, and he planned to keep it that way. |::|

“The case against Caiaphas is that he arrested Jesus, tried him in a kangaroo court and convicted him on a religious charge that carried the death penalty. What were Caiaphas' motives? Jesus threatened Caiaphas's authority. Caiaphas could not afford to allow any upstart preacher to get away with challenging his authority; especially not at Passover time. This was the biggest Jewish festival and scholars estimate that around two and half million Jews would have been in Jerusalem to take part. Caiaphas did not want to lose face.

RELATED ARTICLES:

LAST SUPPER, ARREST OF JESUS AND EVENTS BEFOREHAND

TRIALS OF JESUS africame.factsanddetails.com

TRIALS OF JESUS factsanddetails.com

PONTIUS PILATE: HIS CRUELTY, HISTORY AND ROLE IN THE DEATH OF JESUS africame.factsanddetails.com

PASSION OF CHRIST AND THE WAY OF SORROW factsanddetails.com

CRUCIFIXION OF JESUS, EVENTS AND THE STATIONS OF THE CROSS africame.factsanddetails.com

CRUCIFIXION: HISTORY, EVIDENCE OF IT AND HOW IT WAS DONE europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024