TRANSPORTATION IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Transport overland was slow and expensive. On sea it was cheap, but slow and risky in the winter. Bulky goods were generally carried by ship or riverboat, Travel on the sea was also more comfortable than overland travel. Road travel was either on foot, or sedan chairs or litters for short distances or vehicles drawn by horses, oxen or mules for longer distance. In the springless carriages, carts or chariots it has been imagined that you that bounced and bumped over every cobblestone. Egyptians, Hittites, Aryans, Shang Dynasty Chinese and Assyrians had chariots long before the Greeks and Romans did.

For our knowledge of the means of traveling employed by the Romans we have to rely upon indirect sources, because, if any books of travel were written by Romans they have not come down to us. We know, however, that while no distance was too great to be traversed, no hardships too severe to be surmounted, the Roman in general cared little for travel in itself, for the mere pleasure, that is, of sight-seeing as we enjoy it now. This was partly due to his blindness to the charms of nature in its wilder aspects, more perhaps to the feeling that to be out of Rome was to be forgotten. He made once in his life the grand tour, when he visited famous cities and strange or historic sites; he spent a year abroad, in the train of some general or governor, but, this done, only the most urgent private affairs or public duties could draw him from Italy. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

And Italy meant to him only Rome and his country estates. These he visited when the hot months had closed the courts and adjourned the senate; he roamed restlessly from one estate to another, enjoying the beauty of the Italian landscape, but impatient for his real life to begin again. Even when public or private business called him from Rome, he kept in touch with affairs by correspondence; he expected his friends to write him voluminous letters, and was ready himself to return the favor when positions should be reversed. So, too, the proconsul kept as near to Rome as the boundaries of his province would permit.

The lack of public conveyances running on regular schedules makes it impossible to tell the speed ordinarily made by travelers. Speed depended upon the total distance to be covered, the degree of comfort demanded by the traveler, the urgency of his business, and the facilities at his command. Cicero speaks of fifty-six miles in ten hours by cart as something unusual, but on Roman roads it ought to have been possible to go much faster, if fresh horses were provided at the proper distances, and if the traveler could stand the fatigue. The sending of letters gives the best standard of comparison. There was no public postal service, but every Roman of position had among his slaves special messengers (tabellarii), whose business it was to deliver important letters for him. They covered from twenty-six to twenty-seven miles on foot in a day, and from forty to fifty in carts. We know that letters were sent from Rome to Brundisium, 370 miles, in six days, and on to Athens in fifteen more. A letter from Sicily would read Rome on the seventh day, from Africa on the twenty-first day, from Britain on the thirty-third day, and from Syria on the fiftieth day. In the time of Washington it was no unusual thing for a letter to take a month to go from the eastern to the southern states in winter. “|+|

RELATED ARTICLES:

WATER TRANSPORTATION IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE: SEAGOING SHIPS, RIVER BOATS, PIRATES factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ROADS: CONSTRUCTION, ROUTES AND THE MILITARY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN INFRASTRUCTURE: BRIDGES, TUNNELS, PORTS factsanddetails.com ;

COMMUNICATIONS IN ANCIENT ROME: POSTAL SERVICE, SOCIAL MEDIA, SIGNALS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Travel and Geography in the Roman Empire” by Colin Adams and Ray Laurence (2011) Amazon.com;

“Chariots and Other Wheeled Vehicles in Italy Before the Roman Empire” by J. H. Crouwel (2012) Amazon.com;

“Trade, Transport and Society in the Ancient World: A Sourcebook” ”” (Routledge Revivals) by Onno Van Nijf and Fik Meijer (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Rhetoric of Roman Transportation: Vehicles in Latin Literature”

by Jared Hudson (2021) Amazon.com;

“Land Transport in Roman Egypt: A Study of Economics and Administration in a Roman Province” by Colin Adams (2007) Amazon.com;

“Not All Roads Lead to Rome: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Mobility in the Ancient World” by Arnau Lario Devesa, Joan Campmany Jimnez, et al. (2023) Amazon.com;

“On Horsemanship” by Xenophon Amazon.com;

“The Culture of Animals in Antiquity” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones and Sian Lewis (2020) Amazon.com;

“Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity” by Thorsten Fögen and Edmund V. Thomas (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony (2010) Amazon.com;

“Chariot Racing in the Roman Empire” by Fik Meijer, Liz Waters (2010) Amazon.com;

“Chasing Chariots: Proceedings of the First International Chariot Conference” (Cairo 2012)

by Dr. Andre J. Veldmeijer and Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Roads of the Romans” (J. Paul Getty Museum) by Romolo Staccioli (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Secret History of the Roman Roads of Britain” by M.C. Bishop (2019) Amazon.com;

“Roads in Roman Britain” by Hugh Davies (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Traffic Systems of Pompeii” by Eric E. Poehler (2017) Amazon.com;

“Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World” by Richard J.A. Talbert (2000) Amazon.com;

“Roads in the Deserts of Roman Egypt: Analysis, Atlas, Commentary” by Maciej Paprocki | (2019) Amazon.com;

“Roman Roads: New Evidence - New Perspectives” by Anne Kolb (2021) Amazon.com;

“Roads and Bridges of the Roman Empire” by Horst Barow and Friedrich Ragette (2013)

Amazon.com;

“Roman Bridges” by Colin O'Connor (1994) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Life in Ancient Rome: People & Places”, 450 Pictures, Maps And Artworks,

by Nigel Rodgers (2014) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Land Travel in the Roman Empire

Roman bridge in Turkey The Roman who traveled by land was distinctly better off than Americans of the time of the Revolution. His inns were not so good, it is true, but his vehicles and horses were fully equal to theirs, and his roads were the best that have been built until very recent times. Horseback riding was not a recognized mode of traveling (the Romans had no saddles), but there were vehicles, covered and uncovered, with two wheels and with four, for one horse and for two or more. These were kept for hire outside the gates of all important towns, but the price is not known. To save the trouble of loading and unloading the baggage it is probable that persons going great distances took their own vehicles and merely hired fresh horses from time to time. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“There were, however, no post-routes and no places where horses were changed at the end of regular stages for ordinary travelers, though there were such arrangements for couriers and officers of the government, especially in the provinces. For short journeys and when haste was not necessary, travelers would naturally use their own horses as well as their own carriages. Of the pomp which often accompanied such journeys. |+|

“The streets of Rome were so narrow that wagons and carriages were not allowed upon them at hours when they were likely to be thronged with people. Through many years of the Republic, and for at least two centuries afterwards, the streets were closed to all vehicles during the first ten hours of the day, with the exception of four classes only: market wagons, which brought produce into the city by night and were allowed to leave empty the next morning, transfer wagons (plaustra) conveying material for public buildings, the carriages used by the Vestals, flamines, and rex sacrorum in their priestly functions, and the chariots driven in the pompa circensis and in triumphal processions. Similar regulations were in force in almost all Italian towns. This, in imperial times, made general the use within the walls of the lectica and its bearers. (See illustration in Walters under lectica, and Sandys, Companion, page 209.) Besides the litter in which the passenger reclined, a sedan chair in which he sat erect was common. Both were covered and curtained. The lectica was sometimes used for short journeys, and in place of the six or eight bearers, mules were sometimes put between the shafts, one before and one behind, but not until late in the Empire. Such a litter was called basterna. |+|

Road Travel in the Roman Empire

Road at Leptis Magna in Libya

Most traffic — soldiers, chariots, animals, carts, pedestrians — moved pretty slowly. Milestones inscribed with various kinds of information, such as distance to the next town, marked the Roman miles (measurements of 1,620 yards) on the major Roman roads.

By examining ruts left by cart and carriage wheels in the stone streets, archaeologists have surmised the Romans had one way streets and no-left-turn intersections. National Geographic writer James Cerruti had always wondered whether Roman carts and carriages drove on the right side of the road or the left side. When he saw grooves in the a section of the ancient Appian Way he realized they drove the same way Italians often do today: straight down the middle."

The Roman empire's major highway was the Via Salaria (Salt Road), on which salt was carried from the salt pans of Ostia to Rome. The Via Domitia connected Italy to Spain, the Via Egnatia linked Rome to Byzantium. An eastward extension of the Via Egnatia, the famed road to Damascus, ran across Turkey and southward to Beruit and Syria.

The Roman armies built pontoon bridges to move across waterways and used horses to scout out the enemy on reconnaissance missions. Trajan built a great bridge across the Danube, a startling achievement for its times, to aid his conquest of Dacia The bridge and battles from the Dacian campaign are immortalized in 200 meters of scenes that spiral around the 100-foot-high Trajan column. Trajan's bridge was torn down by Hadrian who felt that it might facilitate a Barbarian conquest of Rome.

Local people needed passport to travel on the official routes. There were no real addresses. Few streets had names and those that did didn't have signs or numbers. Messengers could cover a distance of about 200 miles a day by on main roads by changing horses every 10 miles or so, pony express-style. Traveling in this fashion it took only about six days to reach Britain from Rome (a record that was not improved upon until the invention of modern automobiles in the 20th century).

Roads in the Roman Empire

The Romans built over 53,000 miles of paved roads, stretching from Scotland to East Europe to Mesopotamia in present-day Iraq to North Africa. It was the greatest system of highways that the world has ever seen until recent times. Roman roads were built primarily to facilitate the movement of troops and supplies. Roman legionnaires would not have been nearly as effective in their conquests if getting them supplies was difficult. The system was so well set up that commanders could accurately calculate how long it would take to get their armies from one place to another: from Cologne to Rome was 67 days, Rome to Brindisis, 57 days, and Rome to Syria (including two days at sea), 124 days. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The Romans built over 85,000 kilometers (53,000 miles) of stone-paved roads, stretching from Scotland to East Europe to Mesopotamia in present-day Iraq to North Africa. It was the greatest system of highways that the world has ever seen until recent times. Roman roads were built primarily to facilitate the movement of troops and supplies. Roman legionnaires would not have been nearly as effective in their conquests if getting them supplies was difficult. The system was so well set up that commanders could accurately calculate how long it would take to get their armies from one place to another: from Cologne to Rome was 67 days, Rome to Brindisis, 57 days, and Rome to Syria (including two days at sea), 124 days. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Roman roads were one of the main factors that allowed the ancient Romans to build, maintain and defend such a massive empire. These roads were so well designed and well constructed that some are still in use today. The saying "All roads lead to Rome" may not have been totally 100 percent accurate but it wasn’t that far removed from reality. [Source: P. Andrew Karam, Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery, Encyclopedia.com]

The engineering skill of the Romans and the lavish outlay of money made their roads can not be overstated. They were mainly military works, built for strategic purposes, intended to facilitate the dispatching of supplies to the frontier and the massing of troops in the shortest possible time. Beginning with the first important acquisition of territory in Italy (the Via Appia was built in 312 B.C.) they kept pace with the expansion of the Republic and the Empire, so that a great network of roads covered the Roman world. In Britain, for instance, the roads, some of which are still in use, converged at Londinium (London). [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

The surface of the roads was rounded, and there were gutters at the sides to carry off rain and melted snow. Milestones showed the distance from the starting-point of the road and often that to important places in the opposite direction, as well as the names of the consuls or emperors under whom the roads were built or repaired. The roadbed was wide enough to permit the meeting and passing, without trouble, of the largest wagons. For the pedestrian there was a footpath on either side, sometimes paved, and seats for him to rest upon were often built by the milestones. The horseman found blocks of stone set here and there for his convenience in mounting and dismounting. Where springs were discovered, wayside fountains for men and watering-troughs for cattle were constructed. Such roads often went a hundred years without repairs, and some portions of them have endured the traffic of centuries and are still in good condition today.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ROMAN ROADS: CONSTRUCTION, ROUTES AND MILITARY europe.factsanddetails.com

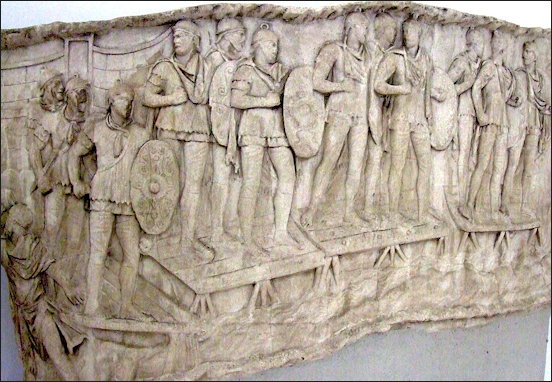

Engineering corps river crossing

Passages of Rivers by the Ancient Romans

Describing the passages of rivers by the Roman military, Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450) wrote in “De Re Militari”: “The passages of rivers are very dangerous without great precaution. In crossing broad or rapid streams, the baggage, servants, and sometimes the most indolent soldiers are in danger of being lost. Having first sounded the ford, two lines of the best mounted cavalry are ranged at a convenient distance entirely across the river, so that the infantry and baggage may pass between them. The line above the ford breaks the violence of the stream, and the line below recovers and transports the men carried away by the current. When the river is too deep to be forded either by the cavalry or infantry, the water is drawn off, if it runs in a plain, by cutting a great number of trenches, and thus it is passed with ease. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

Navigable rivers are passed by means of piles driven into the bottom and floored with planks; or in a sudden emergency by fastening together a number of empty casks and covering them with boards. The cavalry, throwing off their accoutrements, make small floats of dry reeds or rushes on which they lay their rams and cuirasses to preserve them from being wet. They themselves swim their horses across the river and draw the floats after them by a leather thong.

But the most commodious invention is that of the small boats hollowed out of one piece of timber and very light both by their make and the quality of the wood. The army always has a number of these boats upon carriages, together with a sufficient quantity of planks and iron nails. Thus with the help of cables to lash the boats together, a bridge is instantly constructed, which for the time has the solidity of a bridge of stone.

“As the enemy generally endeavor to fall upon an army at the passage of a river either by surprise or ambuscade, it is necessary to secure both sides thereof by strong detachments so that the troops may not be attacked and defeated while separated by the channel of the river. But it is still safer to palisade both the posts, since this will enable you to sustain any attempt without much loss. If the bridge is wanted, not only for the present transportation of the troops but also for their return and for convoys, it will be proper to throw up works with large ditches to cover each head of the bridge, with a sufficient number of men to defend them as long as the circumstances of affairs require.

Traffic in Ancient Rome City

All communications in the city were dominated by this contrast between night and day. By day there reigned intense animation, a breathless jostle, an infernal din. The tabernae were crowded as soon as they opened and spread their displays into the street. Here barbers shaved their customers in the middle of the fairway. There the hawkers from Transtiberina passed along, bartering their packets of sulphur matches for glass trinkets. Elsewhere, the owner of a cook-shop, hoarse with calling to deaf ears, displayed his sausages piping hot in their saucepan. Schoolmasters and their pupils shouted themselves hoarse in the open air. At the cross-roads a circle of idlers gaped round a viper tamer; everywhere tinkers' hammers resounded and the quavering voices of beggars invoked the name of Bellona or rehearsed their adventures and misfortunes to touch the hearts of the passers-by. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The flow of pedestrians was unceasing and the obstacles to their progress did not prevent the stream soon becoming a torrent. In sun or shade a whole world of people came and went, shouted, squeezed, and thrust through narrow lanes unworthy of a country village. Ordinary men had by now sought sanctuary in their homes, but the human stream was, by Caesar's decree, succeeded by a procession of beasts of burden, carts, their drivers, and their escorts. The great dictator had realised that in alleyways so steep, so narrow, and so traftic-ridden as the vici of Rome the circulation by day of vehicles serving the needs of a population of so many hundreds of thousands caused an immediate congestion and constituted a permanent danger. He therefore took the radical and decisive step which his law proclaimed. From sunrise until nearly dusk no transport cart was henceforward to be allowed within the precincts of the Urbs. Those which had entered during the night and had been overtaken by the dawn must halt and stand empty. To this inflexible rule four exceptions alone were permitted: on days of solemn ceremony., the chariots of the Vestals, of the Rex Sacrorum, and of the Flamines; on days of triumph, the chariots necessary to the triumphal procession; on days of public games, those which the official celebration required. Lastly one perpetual exception was made for every day of the year in favor of the carts of the contractors who were engaged in wrecking a building to reconstruct it on better and hygienic lines.

Apart from these few clearly defined cases, no daytime traffic was allowed in ancient Rome except for pedestrians, horsemen, litters, and carrying chairs. Whether it was a pauper funeral setting forth at nightfall or majestic obsequies gorgeously carried out in full daylight. On the other hand, the approach of night brought with it the legitimate commotion of wheeled carts of every sort which filled the city with their racket. Later, Claudius extended the rules to the municipalities of Italy; Marcus Aurelius to every city of the empire without regard to its own municipal statutes; Hadrian limited the teams and the loads of the carts allowed to enter the city; and at the end of the first century and the beginning of the second we find the writers of the day reflecting the image of a Rome still definitely governed by the decrees of Julius Caesar.

According to Juvenal the incessant night traffic and the hum of noise condemned the Roman to everlasting insomnia. "What sleep is possible in a lodging?" he asks. "The crossing of waggons in the narrow, winding streets, the swearing of drovers brought to a standstill would snatch sleep from a sea-calf or the emperor Claudius himself." Amid the intolerable thronging of the day against which the poet inveighs immediately after, we detect above the hurly-burly of folk on foot only the swaying of a Liburnian litter. The herd of people which sweeps the poet along proceeds on foot through a scrimmage that is constantly renewed. The crowd ahead impedes his hasty progress, the crowd behind threatens to crush his loins. One man jostles him with his elbow, another with a beam he is carrying, a third bangs his head with a wine-cask. A mighty boot tramps on his foot, a military nail embeds itself in his toe, and his newly mended tunic is torn. Then of a sudden panic ensues: a waggon appears, on top of which a huge log is swaying, another follows loaded with a whole pine tree, yet a third carrying a cargo of Ligurian marble. "If the axle breaks and pours its contents on the crowd, what will be left of their bodies?"

Ancient Roman Carriages and Carts

Roman stagecoach Monuments show us rude representations of several kinds of vehicles and the names of at least eight have come down to us, but we are not able positively to connect the representations and the names, and have, therefore, only very general notions of the form and construction of even the most common. Some, of ancient design, were retained wholly, or chiefly, for use as state carriages in the processions that have been mentioned. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Pilentum and Carpentum were among the most common vehicles in ancient Rome. The former had four wheels, the latter had two. Both were covered, both drawn by two horses, both used by the Vestals and priests. The carpentum is rarely spoken of as a traveling carriage; its use for such a purpose was a mark of luxury. According to Livy, the first Tarquin came from Etruria to Rome in a carpentum.The petoritum also was used in the triumphal processions, but only for the spoils of war. It was essentially a baggage wagon and was occupied by the servants in a traveler’s train. The carruca was a luxurious traveling van, of which we hear first in the late Empire. It was furnished with a bed on which the traveler reclined by day and slept by night.

Raeda and Cisium: The usual traveling vehicles, however, were the raeda and the cisium. The former was large and heavy, covered, had four wheels, and was drawn by two or four horses. It was regularly used by persons accompanied by their families or having baggage with them, and was kept for hire for this purpose. For a rapid journey, when a man had no traveling companions and little baggage, the two-wheeled and uncovered cisium was the favorite vehicle. It was drawn by two horses, one between shafts and the other attached by traces; it is possible that three were sometimes used. The cisium had a single seat, broad enough to accommodate a driver also. It is very likely that the cart on a monument found near Trèves is a cisium, but the identification is not certain. |+|

Cicero speaks of these carts making fifty-six miles in ten hours, probably with one or more changes of horses. Other vehicles of the cart type that came into use during the Empire were the essedum and the covinus, but we do not know how they differed from the cisium. These carts had no springs, but the traveler took care to have plenty of cushions. It is worth noticing that none of the vehicles mentioned has a Latin name; the names, with perhaps one exception (pilentum), are Celtic. In like manner, most of our own carriages had foreign names, and many French terms came in with the automobile.

First Wheels and Wheeled Vehicles

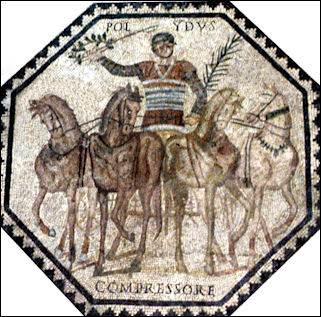

Roman chariot race

The wheel, some scholars have theorized, was first used to make pottery and then was adapted for wagons and chariots. The potter's wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in 4000 B.C. Some scholars have speculated that the wheel on carts were developed by placing a potters wheel on its side. Other say: first there were sleds, then rollers and finally wheels. Logs and other rollers were widely used in the ancient world to move heavy objects. It is believed that 6000-year-old megaliths that weighed many tons were moved by placing them on smooth logs and pulling them by teams of laborers.

Early wheeled vehicles were wagons and sleds with a wheel attached to each side. The wheel was most likely invented before around 3000 B.C — the approximate age of the oldest wheel specimens — as most early wheels were probably shaped from wood, which rots, and there isn't any evidence of them today. The evidence we do have consists of impressions left behind in ancient tombs, images on pottery and ancient models of wheeled carts fashioned from pottery."

In 2003 — at a site in the Ljubljana marshes, Slovenia, 20 kilometers southeast of Ljubljana — Slovenian scientists claimed they found the world's oldest wheel and axle. Dated with radiocarbon method by experts in Vienna to be between 5,100 and 5,350 years old the found in the remains of a pile'dwelling settlement, the wheel has a radius of 70 centimeters and is five centimeters thick. It is made of ash and oak. Surprisingly technologically advanced, it was made of two ashen panels of the same tree. The axle, whose age could not be precisely established, is about as old as the wheel. It is 120 centimeters long and made of oak. [Source: Slovenia News]

See Separate Article ANCIENT HORSEMEN AND THE FIRST WHEELS, CHARIOTS AND MOUNTED RIDERS factsanddetails.com

Ceremonial Carriage Found in Pompeii

In February 2021, archaeologists announced that they had unearthed a unique ancient-Roman ceremonial carriage from a villa just outside Pompeii, which was buried by Vesuvius volcanic eruption in A.D. 79. The almost perfectly preserved four-wheeled carriage made of iron, bronze and tin was found near the stables of an ancient villa at Civita Giuliana, around 700 meters (yards) north of the walls of ancient Pompeii. Massimo Osanna, the former director of the Pompeii archaeological site, said the carriage would have "accompanied festive moments for the community, (such as) parades and processions" and was the first of its kind discovered in the area, which had so far yielded functional vehicles used for transport and work, but not for ceremonies. [Source: Reuters, February 27, 2021]

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The chariot, which could seat one or two people, was discovered in a portico adjoining a stable where researchers uncovered the remains of three horses in 2018. The chariot is extremely fragile, so archaeologists digitally documented it before dismantling it into 112 pieces, which they brought to a lab for further analysis and restoration. They also made plaster casts of impressions left by decayed organic material, including the chariot’s wooden steering shaft and ropes that linked mechanical elements of its ironclad wheels. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2022]

Researchers believe the chariot is a pilentum, a type of vehicle known only from ancient sources that mention it was used by high-status women and priestesses. Its wooden sides are painted red and black and bear traces of floral motifs. On the vehicle’s rear, circular reliefs made of bronze and other metals feature erotic images, including scenes of frolicking followers of the wine god, Bacchus, and of the god of love, Eros. “The decoration is clearly related to the world of love,” says archaeologist Luana Toniolo of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii. “That’s why we initially thought the chariot could be connected with weddings. Now we think that it was probably used in some kind of countryside ritual.”

Remains of Three Harnessed Horses Found at Pompeii Villa

The History Blog reported: In 2018, the skeleton of a horse who died wearing an elaborate harness and saddle have been unearthed at an elite villa on the outskirts of Pompeii. This is the third set of horse remains discovered at the estate north of the city walls, the first of which was the first confirmed horse ever found at Pompeii. [Source The History Blog, December 26, 2018]

Excavations began in March 2018 as an emergency response to looting activity. Tunnels dug underneath the villa by thieves were endangering the archaeological material. The dig brought to light a series of service areas of the grand suburban villa with artifacts preserved in exceptional condition. Amphorae, cooking utensils, even parts of a wooden bed were recovered, and a plaster cast was made of the entire bed.

One of the service areas that could be identified is the stable. Archaeologists unearthed the first horse lying on its side and were able to make a plaster cast from the cavity the horse’s body had left in the hardened volcanic rock. They then unearthed the legs of a second horse. This year the team excavated the rest of the stable, revealing the rest of the remains of the second horse and the skeleton of a third complete with its harness.

The former was found lying on its right side, skull on top of the left front leg. It was next to charred wood pieces from a manger (also cast in plaster). The position suggests that the poor horse was tied to it and could not get away when Vesuvius’ pyroclastic fury hit the stable. The third horse was found on its left side, an iron bit clenched between its teeth. The looting tunnels exposed the cavity and cementified it made it impossible to make a plaster cast of it.

The excavation of the third horse revealed five bronze objects: four wood pieces of half-moon shape coated in bronze found on the ribs, one bronze piece made of three hooks riveted to a ring connected to a disc. It was found under the belly near the front legs. The shapes and design of these parts suggest they were part of a saddle that is described in ancient sources. It was a wooden structure with four horns, two in the front, two in the rear, covered with bronze plates. This firm saddle gave the rider stability in an era before stirrups.

Saddles of this kind were used from the early imperial era particularly by members of the military. The ring junction, four for each harness, were used to connect leather straps to the saddle horns. This was rich, expensive tack that would have belonged to someone of very high rank. The artifacts found strongly indicate that this horse belonged to a Roman military officer and had been saddled likely in the hope of escaping the eruption. Vesuvius got to human and equines before they had a chance.

Ancient Roman Inns

plan of a Roman inn described to the right

Jesús Rodríguez Morales wrote in National Geographic History: To help travelers stay fresh, they could stop at a mansio, an official service establishment that sprang up along Roman roads. Hostels and relay stations were located at a distance equivalent to one day’s worth of travel, typically about 20 to 25 Roman miles. These facilities, grouped around a central courtyard, had stables and troughs for the horses, a place to eat, and sleeping quarters. Some offered public baths so travelers could wash off the dust.[Source: Jesús Rodríguez Morales, National Geographic History, January 22, 2021]

There were numerous lodging houses and restaurants in all the cities and towns of Italy, but all were of the meanest character. Respectable travelers avoided them scrupulously; they either had stopping-places of their own (deversoria) on roads that they used frequently, or claimed entertainment from friends and hospites, whom they would be sure to have everywhere. Nothing but accident, stress of weather, or unusual haste could drive them to places of public entertainment (tabernae deversoriae, cauponae). [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

The guests of such places were, therefore, of the lowest class, and innkeepers (caupones) and inns bore the most unsavory reputations. Food and beds were furnished the travelers, and their horses were accommodated under the same roof and in unpleasant proximity. The plan of an inn at Pompeii may be taken as a fair sample of all such houses. The entrance (a) is broad enough to admit wagons into the wagon-room (f), behind which is the stable (k). In one corner is a watering-trough (l), in another a latrina (i). On either side of the entrance is a wine-room (b, d), with the room of the proprietor (c) opening off one of them. The small rooms (e, g, h) are bedrooms, and other bedrooms in the second story over the wagon-room were reached by the back stairway.

The front stairway has an entrance of its own from the street; the rooms reached by it had probably no connection with the inn. Behind this stairway on the lower floor was a fireplace (m) with a water heater. An idea of the moderate prices charged in such places may be had from a bill which has come down to us in an inscription preserved in the Museum at Naples: a pint of wine with bread, one cent; other food, two cents; hay for a mule, two cents. The corners of streets, especially at points close to the city walls, were the favorite sites for inns, and they had signs (the elephant, the eagle, etc.) like those of much later times.” Innkeepers inscribed wine lists and prices on the wall of their facilities. |+|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024