AGRICULTURE IN ANCIENT ROME

Harvesting grapes Food was never a problem in Rome. The land around the city was productive and as the empire expanded it was fed by fertile land in Tunis and Algeria and the Crimea. Virgil wrote: "How blessed beyond all blessings are farmers, if they but knew their happiness! Far from the clash of arms, the moist earth brings forth an easy living for them."

Farms were largely manned by slaves. As farms became larger and more people moved to the cities the number of rural landowners decreased and they became less powerful. Power became centered in the cities, namely Rome itself, and a dominant urban political class ruled the empire until Caesar turned the emperorship in a dictatorship.

The soil of Italy is generally fertile, especially in the plains of the Po and the fields of Campania. The staple products in ancient times were wheat, the olive, and the vine. For a long period Italy took the lead of the world in the production of olive oil and wine. The production of wheat declined when Rome, by her conquests, came into commercial relation with more fertile countries, such as Egypt. \~\

In addition to casual references in literature our sources of information about Roman farming include treatises on the subject by the Elder Cato, who wrote in the second century B.C., Varro and Vergil, at the beginning of our era, Columella and Pliny the Elder in the first century A.D., and Palladius in the fourth. Works of art occasionally show something of the implements used. Excavations have brought to light remains of villas in different parts of the Roman world, and occasionally metal parts of implements have been found. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Agriculture was the industry of early Italy. The great number of rural festivals in the calendar testifies to its dominating influence. The interests of the Romans of all times were agricultural rather than commercial. Agriculture was the proper business of the senatorial class. Writers of all periods looked back to the days when a Roman citizen-farmer tilled his own land with the help of a slave or two and when a dictator might be called from the plow. |+|

RELATED ARTICLES:

FARMING AND RURAL LIFE IN THE ROMAN ERA factsanddetails.com ;

CROPS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE: MOSTLY GRAINS, OLIVES AND FRUITS factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN LIVESTOCK AND FISHING: PIGS, TUNA AND WHALES? factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Roman Agricultural Economy: Organization, Investment, and Production”

by Alan Bowman and Andrew Wilson (2013) Amazon.com;

“Farmers and Agriculture in the Roman Economy” by David B. Hollander (2018) Amazon.com;

“Bringing in the Sheaves: Economy and Metaphor in the Roman World”

by Brent Shaw (2015) Amazon.com;

“Roman Farming” by K. D. White (1970) Amazon.com;

“Agricultural Implements of the Roman World” by K. D. White (1967) Amazon.com;

“Cato: On Farming - De Agricultura” by Cato, translated by Andrew Dalby Amazon.com;

“Roman Farm Management The Treatises of Cato and Varro”, translated by Fairfax Harrison (1869-1938) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Ancient Agriculture (Blackwell) by David Hollander and Timothy Howe (2020) Amazon.com;

“Agricola; a Study of Agriculture and Rustic Life in the Greco-Roman World From the Point of View of Labour: by William Emerton Heitland (1847-1935) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Market Economy” by Peter Temin (2012) Amazon.com;

“Food and Drink in Antiquity: A Sourcebook: Readings from the Graeco-Roman World” (Bloomsbury Sources in Ancient History) by John F. Donahue (2015) Amazon.com;

“Food in Roman Britain” by Joan P. Alcock (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Grain Market in the Roman Empire: A Social, Political and Economic Study”

by Paul Erdkamp (2005) Amazon.com;

“Land and Labour: Studies in Roman Social and Economic History” by Jesper Carlsen (2013) Amazon.com;

“London's Roman Tools: Craft, Agriculture and Experience in an Ancient City” by Owen Humphreys (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Rome Olive Guide: Olive Trees, Fruit, Oil & Recipes” by Pliny, Columella, et al. | (2021) Amazon.com;

“Roman and Late Antique Wine Production in the Eastern Mediterranean: A Comparative Archaeological Study at Antiochia ad Cragum (Turkey) and Delos (Greece)” by Emlyn Dodd | (2020) Amazon.com;

“Wine in Ancient Greece and Cyprus: Production, Trade and Social Significance”

by Evi Margaritis, Jane M. Renfrew, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“From Vines to Wines in Classical Rome” by David L. Thurmond (2016) Amazon.com;

“Rome at War: Farms, Families, and Death in the Middle Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Resilience of the Roman Empire: Regional Case Studies on the Relationship Between Population and Food Resources” by Dimitri Van Limbergen, Sadi Maréchal, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Food Provisions for Ancient Rome: A Supply Chain Approach” by Paul James (2020) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis”

by Peter Garnsey (1988) Amazon.com;

“On Horsemanship” by Xenophon Amazon.com;

“The Culture of Animals in Antiquity” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones and Sian Lewis (2020) Amazon.com;

“Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity” by Thorsten Fögen and Edmund V. Thomas (2017) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Natural Conditions in Italy for Producing Food

Italy is blessed above all the other countries of central Europe with the natural conditions that go to yield an abundant and varied supply of food. The soil is rich and composed of different elements in different parts of the country. The rainfall is abundant, and rivers and smaller streams are numerous. The line of greatest length runs northwest to southeast, but the climate depends little upon latitude, as it is modified by surrounding bodies of water, by mountain ranges, and by prevailing winds. These agencies in connection with the varying elevations of the land itself produce such widely different conditions that somewhere within the confines of Italy almost all the grains and fruits of the temperate and subtropic zones find the soil and climate most favorable to their growth. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Roman agricultural machine

“The volcanic ash that formed the plain of Latium gave a subsoil rich in potash and phosphate, but the surface soil was thin and easily exhausted. Great forests once grew on plains and hills that have been bare for centuries. Cutting the timber from the hills caused erosion and rendered much land unproductive. With the lack of forests on the hills to retain moisture the seasons in the lowland were affected.” |+|

“The earliest inhabitants of the peninsula, the Italian peoples, seem to have left for the Romans the task of developing and improving these means of subsistence. Wild fruits, nuts, and flesh have always been the support of uncivilized peoples, and must have been so for the shepherds who laid the foundations of Rome. The very word pecunia (from pecu; cf. peculium), shows that herds of domestic animals were the first source of Roman wealth. But other words show just as clearly that the cultivation of the soil was understood by the Romans in very early times: the names Fabius, Cicero, Piso, and Caepio are no lessancient than Porcius, Asinius, Vitellius, and Ovidius. Cicero puts into the mouth of the Elder Cato the statement that to the farmer the garden was a second meat supply, but long before Cato’s time meat had ceased to be the chief article of food. Grain and grapes and olives furnished subsistence for all who did not live to eat. These gave “the wine that maketh glad the heart of man, and oil to make his face to shine, and bread that strengtheneth man’s heart.” On these three abundant products of the soil the mass of the people of Italy lived of old as they live today. Something will be said of each, after less important products have been considered.” |+|

Food also came from elsewhere in the Mediterranean. A satirical poem by Varro, a contemporary of Cicero, lists peacock from Samos, heath-cock from Phrygia, crane from Media, kid from Ambracia, young tunny-fish from Chalcedon, murena from Tartessus, cod from Pessinus, oysters from Tarentum, scallops from Chios, sturgeon from Rhodes, scarus from Cilicia, nuts from Thasos, dates from Egypt, and chestnuts from Spain. |+|

Development of Agriculture

Agriculture began around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. Considered the most important human advance after the control of fire and the creation of tools, it allowed people to settle in specific areas and freed them from hunting and gathering. According to the Bible, Cain and Abel, the sons of Adam and Eve, developed agriculture and domesticated animals, .”Now Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground,.” the Bible reads.

Roman soldiers were punished by being given barley instead of wheat

The first documented agriculture occurred 11,500 year ago in what Harvard archaeologist Ofer Ban-Yosef calls the Levantine Corridor, between Jericho in the Jordan Valley and Mureybet in the Euphrates Valley. At Mureybit, a site on the banks of the Euphrates, seeds from an uplands area — where the plants from the seeds grow naturally — were found and dated to 11,500 years ago. An abundance of seeds from plants that grew elsewhere found near human sites is offered as evidence of agriculture.

Wheat and barley agriculture spread out of Fertile crescent by 7000 B.C. By 6000 B.C., it had gotten as far as the Black Sea and present day Greece and Italy. By 5000 B.C. it had spread to most of southern Europe. The Linear Pottery Culture of central Hungary is believed to have introduced agriculture to central Europe around 5000 B.C. Agriculture finally reached southern Britain and Scandinavia around 3800 B.C. and north Britain and central Scandinavia by 2,500 B.C.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ORIGIN AND EARLY HISTORY OF AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com ;

IMPORTANT EARLY DEVELOPMENTS IN AGRICULTURE: PLOUGHING, FERTILIZER, IRRIGATION factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST GRAINS AND CROPS: BARLEY, WHEAT, MILLET, SORGHUM, RICE AND CORN factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST NON-GRAIN CROPS: NUTS, FIGS, BEANS, OLIVES, FRUIT AND POTATOES factsanddetails.com

SPREAD OF AGRICULTURE TO EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com

Noble Farmers in the Roman Empire

The farm life that Cicero has described so eloquently and praised so enthusiastically in his Cato Maior would have scarcely been recognized by Cato himself and, long before Cicero wrote, had become a memory or a dream. The farmer no longer tilled his fields, even with the help of his slaves. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The yeoman class had largely disappeared from Italy. Many small holdings had been absorbed in the vast estates of the wealthy landowners, and the aims and methods of farming had wholly changed. This is discussed elsewhere, and it will be sufficient here to recall the fact that in Italy grain was no longer raised for the market, simply because the market could be supplied more cheaply from overseas. |+|

“The grape and the olive had become the chief sources of wealth, and Sallust and Horace complained that for them less and less space was being left by the parks and pleasure grounds. Still, the making of wine and oil under the direction of a careful steward must have been very profitable in Italy, and many of the nobles had plantations in the provinces as well, the revenues of which helped to maintain their state at Rome. Further, certain industries that naturally arose from the soil were considered proper enough for a senator, such as the development and management of stone quarries, brickyards, tile works, and potteries.” |+|

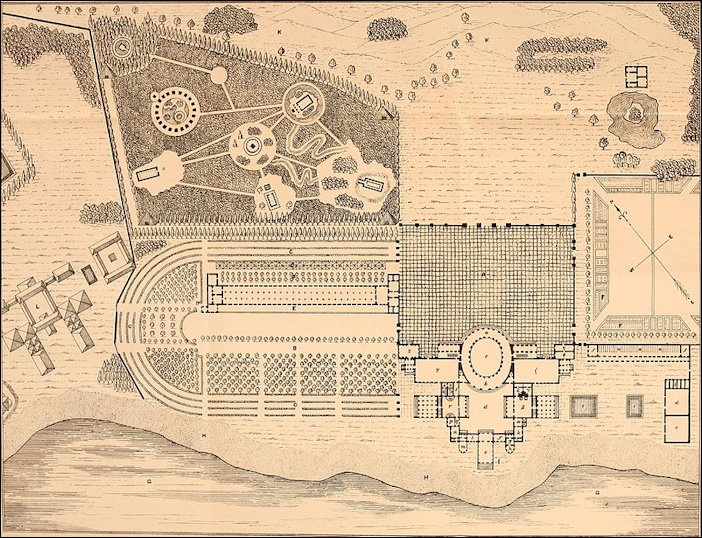

Country Houses in the Roman Era

Country estates might be of two classes, countryseats for pleasure and farms for profit. In the first case the location of the house (villa urbana, or pseudourbana), the arrangement of the rooms and the courts, their number and decoration, would depend entirely upon the taste and means of the master. Remains of such houses in most varied styles and plans have been found in various parts of the Roman world, and accounts of others in more or less detail have come down to us in literature, particularly the descriptions of two of his villas given by Pliny the Younger. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

plan of a Roman estate

“Some villas were set in the hills for coolness, and some near the water. In the latter case rooms might be built overhanging the water, and at Baiae, the fashionable seaside resort, villas were actually built on piles so as to extend from the shore out over the sea. Cicero, who did not consider himself a rich man, had at least six villas in different localities. The number is less surprising when one remembers that there were nowhere the seaside or mountain hotels so common now, so that it was necessary to stay in a private house, one’s own or another’s, when one sought to escape from the city for change or rest. |+|

“Vitruvius says that in the country house the peristyle usually came next the front door. Next was the atrium, surrounded by colonnades opening on the palaestra and walks. Such houses were equipped with rooms of all sorts for all occasions and seasons, with baths, libraries, covered walks, gardens, everything that could make for convenience or pleasure. Rooms and colonnades for use in hot weather faced the north; those for winter were planned to catch the sun. Attractive views were taken into account in arranging the rooms and their windows. |+|

Farm Slaves in Ancient Rome

The Familia Rustica. Under the name familia rustica are comprised the slaves that were employed upon the vast estates that long before the end of the Republic had begun to supplant the small farms of the earlier day. The very name points to this change, for it implies that the estate was no longer the only home of the master. He had become a landlord; he lived in the capital and visited his lands only occasionally for pleasure or for business. The estates may, therefore, be divided into two classes: countryseats for pleasure and farms or ranches for profit. The former were selected with great care, the purchaser having regard to their proximity to the city or other resorts of fashion, their healthfulness, and the natural beauty of their scenery. They were maintained upon the most extravagant scale. There were villas and pleasure grounds, parks and game preserves, fish ponds and artificial lakes, everything that ministered to open-air luxury. Great numbers of slaves were required to keep these places in order. Many of them were slaves of the highest class: landscape gardeners, experts in the culture of fruits and flowers, experts even in the breeding and keeping of birds, game, and fish, of which the Romans were inordinately fond. These had under them assistants and laborers of every sort. All the slaves were subject to the authority of a superintendent or steward (vilicus), who had been put in charge of the estate by the master. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Farm Slaves. But the name familia rustica is more characteristically used of the drudges upon the farms, because the slaves employed upon the countryseats were more directly in the personal service of the master and can hardly be said to have been kept for profit. The raising of grain for the market had long ceased to be profitable in Italy; various industries had taken its place upon the farms. Wine and oil had become the most important products of the soil, and vineyards and olive orchards were found wherever climate and other conditions were favorable. Cattle and swine were raised in countless numbers, the former more for draft purposes and the products of the dairy than for beef. Pork, in various forms, was the favorite meat dish of the Romans. Sheep were kept for the wool; woolen garments were worn by the rich and by the poor alike. Cheese was made in large quantities, all the larger because butter was unknown. The keeping of bees was an important industry, because honey served, so far as it could, the purposes for which sugar is used in modern times. Besides these things that we are even now accustomed to associate with farming, there were others that are now looked upon as distinct and separate businesses. Of these the most important, perhaps, as it was undoubtedly the most laborious, was the quarrying of stone. Important, too, were the making of brick and tile, the cutting of timber and working it up into rough lumber, and the preparing of sand for the use of the builder. This last was of much greater importance relatively then than now, on account of the extensive use of concrete at Rome. |+|

slaves carrying amphorae

“In some of these tasks, intelligence and skill were required as they are today, but in many of them the most necessary qualifications were strength and endurance, as the slaves took the place of much of the machinery of modern times. This was especially true of the men employed in the quarries, who were usually of the rudest and most ungovernable class, and were worked in chains by day and housed in dungeons by night. |+|

“The Vilicus. The management of such a farm was also intrusted to a vilicus, who was proverbially a hard taskmaster, simply because his hopes of freedom depended upon the amount of profits he could turn into his master’s coffers at the end of the year. His task was no easy one. Besides overseeing the gangs of slaves already mentioned and planning their work, he might have under his charge another body of slaves, only less numerous, employed in providing for the wants of the others. On the large estates everything necessary for the farm was produced or manufactured on the place, unless conditions made only highly specialized farming profitable. Enough grain was raised for food, and this grain was ground in the farm mills and baked in the farm ovens by millers and bakers who were slaves on the farm. The mill was usually turned by a horse or a mule, but slaves were often made to do the grinding as a punishment. Wool was carded, spun, and woven into cloth, and this cloth was made into clothes by the female slaves under the eye of the steward’s consort, the vilica. Buildings were erected, and the tools and implements necessary for the work of the farm were made and repaired. These things required a number of carpenters, smiths, and masons, though such workmen were not necessarily of the highest class. It was the touchstone of a good vilicus to keep his men always busy, and it is to be understood that the slaves were alternately plowmen and reapers, vinedressers and treaders of the grapes, perhaps even quarrymen and lumbermen, according to the season of the year and the place of their toiling. |+|

Cato the Elder: How to Manage Farm Slaves in Ancient Rome

William Stearns Davis wrote: “Cato the Elder passed as the incarnation of all worldly wisdom among Romans of the second century B.C. The precepts here given were undoubtedly put into effect on his own farms. During the early Republic, when the estates were small, there seems to have been a fair amount of kindly treatment awarded the slaves; as the farms grew larger the whole policy of the masters, by becoming more impersonal, became more brutal. Cato does not advocate deliberate cruelty — he would simply treat the slaves according to cold regulations, like so many expensive cattle.”

Cato the Elder wrote in Agriculture, chs. 56-59: “Country slaves ought to receive in the winter, when they are at work, four modii [Davis: One modius equals about a quarter bushel] of grain; and four modii and a half during the summer. The superintendent, the housekeeper, the watchman, and the shepherd get three modii; slaves in chains four pounds of bread in winter and five pounds from the time when the work of training the vines ought to begin until the figs have ripened. [Source: Cato the Elder, Agriculture, chs. 56-59,William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 90-97]

“Wine for the slaves. After the vintage let them drink from the sour wine for three months. The fourth month let them have a hemina [Davis: about half a pint] per day or two congii and a half [Davis: over seven quarts] per month. During the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth months let them have a sextarius [Davis: about a pint] per day or five congii per month. Finally, in the ninth, tenth, and the eleventh months, let them have three hemina [Davis: three-fourths of a quart] per day, or an amphora [Davis: about six gallons] per month. On the Saturnalia and on Compitalia each man should have a congius [Davis: something under three quarts].

“To feed the slaves. Let the olives that drop of themselves be kept so far as possible. Keep too those harvested olives that do not yield much oil, and husband them, for they last a long time. When the olives have been consumed, give out the brine and vinegar. You should distribute to everyone a sextarius of oil per month. A modius of salt apiece is enough for a year. “As for clothes, give out a tunic of three feet and a half, and a cloak once in two years. When you give a tunic or cloak take back the old ones, to make cassocks out of. Once in two years, good shoes should be given.

“Winter wine for the slaves. Put in a wooden cask ten parts of must (non-fermented wine) and two parts of very pungent vinegar, and add two parts of boiled wine and fifty of sweet water. With a paddle mix all these thrice per day for five days in succession. Add one forty-eighth of seawater drawn some time earlier. Place the lid on the cask and let it ferment for ten days. This wine will last until the solstice. If any remains after that time, it will make very sharp excellent vinegar.”

Food Subsidies in Ancient Rome

Bruce Bartlett wrote in the Cato Institute Journal: “The reason why Egypt retained its special economic system and was not allowed to share in the general economic freedom of the Roman Empire is that it was the main source of Rome’s grain supply. Maintenance of this supply was critical to Rome’s survival, especially due to the policy of distributing free grain (later bread) to all Rome’s citizens which began in 58 B.C. By the time of Augustus, this dole was providing free food for some 200,000 Romans. The emperor paid the cost of this dole out of his own pocket, as well as the cost of games for entertainment, principally from his personal holdings in Egypt. The preservation of uninterrupted grain flows from Egypt to Rome was, therefore, a major task for all Roman emperors and an important base of their power. [Source: Bruce Bartlett, “How Excessive Government Killed Ancient Rome,” Cato Institute Journal 14: 2, Fall 1994, Cato.org /=]

“The free grain policy evolved gradually over a long period of time and went through periodic adjustment. 3 The genesis of this practice dates from Gaius Gracchus, who in 123 B.C. established the policy that all citizens of Rome were entitled to buy a monthly ration of corn at a fixed price. The purpose was not so much to provide a subsidy as to smooth out the seasonal fluctuations in the price of corn by allowing people to pay the same price throughout the year. /=\

ancient Roman agricultural tools

“Under the dictatorship of Sulla, the grain distributions were ended in approximately 90 B.C. By 73 B.C., however, the state was once again providing corn to the citizens of Rome at the same price. In 58 B.C., Clodius abolished the charge and began distributing the grain for free. The result was a sharp increase in the influx of rural poor into Rome, as well as the freeing of many slaves so that they too would qualify for the dole. By the time of Julius Caesar, some 320,000 people were receiving free grain, a number Caesar cut down to about 150,000, probably by being more careful about checking proof of citizenship rather than by restricting traditional eligibility. /=\

“Under Augustus, the number of people eligible for free grain increased again to 320,000. Tn 5 B.C., however, Augustus began restricting the distribution. Eventually the number ofpeople receiving grain stabilized at about 200,000. Apparently, this was an absolute limit and corn distribution was henceforth limited to those with a ticket entitling them to grain. Although subsequent emperors would occasionally extend eligibility for grain to particular groups, such as Nero’s inclusion ofthe Praetorian guard in 65 AD., the overall number of people receiving grain remained basically fixed. /=\

“The distribution of free grain in Rome remained in effect until the end of the Empire, although baked bread replaced corn in the 3rd century. Under Septimius Severus (193—211 AD.) free oil was also distributed. Subsequent emperors added, on occasion, free pork and wine. Eventually, other cities of the Empire also began providing similar benefits, including Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch. /=\

“Nevertheless, despite the free grain policy, the vast bulk of Rome’s grain supply was distributed through the free market. There are two main reasons for this. First, the allotment of free grain was insufficient to live on. Second, grain was available only to adult male Roman citizens, thus excluding the large number of women, children, slaves, foreigners, and other non-citizens living in Rome. Government officials were also excluded from the dole for the most part. Consequently, there remained a large private market for grain which was supplied by independent traders.” /=\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024