MEAT IN ANCIENT ROME

Numidian chicken with beans and cumin, a Roman poultry dish

The Romans ate chicken, wild boar, suckling pig, beef, veal, lamb, goat, kid, deer, hare, pheasant, duck, goose, capon (a castrated rooster) and game birds such as thrush, starling and woodcock. They were particularly fond of goose, which was prepared a number of ways with several different sauces. Rabbits are believed to have been domesticated using wild rabbits from Iberia in the Roman Era.

The forests around Roman cities were filled with game. Small birds and mammals were caught in nets. The Romans used dove cotes to raise birds for eggs and meat and produced three-story-high towers to raise dormice, which were a fixture of Roman meals. Cats, rabbits and peacocks were introduced to Rome and eaten by around the A.D. 1st century.

Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “Besides the pork, beef, and mutton that we still use the Roman farmer had goat’s flesh at his disposal; all of these meats were sold in the towns. Goat’s flesh was considered the poorest of all and was used by the lower classes only. Beef had been eaten by the Romans from the earliest times, but its use was a mark of luxury until very late in the Empire. Under the Republic the ordinary citizen ate beef only on great occasions when he had offered a steer or a cow to the gods in sacrifice. The flesh then furnished a banquet for his family and friends; the heart, liver, and lungs (called collectively the exta) were the share of the priest, while certain portions were consumed on the altar. Probably the great size of the carcass had something to do with the rarity of its use at a time when meat could be kept fresh only in the coldest weather; at any rate we must think of the Romans as using cattle for draft and dairy purposes, rather than for food. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Pork was widely used by rich and poor alike, and was considered the choicest of all domestic meats. The very language testifies to the important place the pig occupied in the economy of the larder, for no other animal has so many words to describe it in its different functions. Besides the general term sus we find porcus, porca, verres, aper, scrofa, maialis, and nefrens. In the religious ceremony of the suovetaurilia (sus + ovis + taurus), the swine, it will be noticed, has the first place, coming before the sheep and the bull. The vocabulary describing the parts of the pig used for food is equally rich; there are words for no less than half a dozen kinds of sausages, for example, with pork as their basis. We read, too, of fifty different ways of cooking pork. |+|

“Fowl and Game. The common domestic fowls—chickens, ducks, geese, as well as pigeons—were eaten by the Romans, and, besides these, the wealthy raised various sorts of wild fowl for the table, in the game preserves that have been mentioned. Among these were cranes, grouse, partridges, snipe, thrushes, and woodcock. In Cicero’s time the peacock was most highly esteemed, having at the feast much the same place of honor as the turkey has with us; the birds cost as much as ten dollars each. Wild animals also were bred for food in similar preserves; the hare and the wild boar were the favorite. The latter was served whole upon the table, as in feudal times. As a contrast in size the dormouse (glis) may be mentioned; it was thought a great delicacy.” |+|

RELATED ARTICLES:

AGRICULTURE IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

FARMING AND RURAL LIFE IN THE ROMAN ERA factsanddetails.com ;

CROPS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE: MOSTLY GRAINS, OLIVES AND FRUITS factsanddetails.com ;

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Culture of Animals in Antiquity” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones and Sian Lewis (2020) Amazon.com;

“Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity” by Thorsten Fögen and Edmund V. Thomas (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Process of Animal Domestication” by Marcelo Sánchez-Villagra (2022) Amazon.com;

“Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches: The Riddles of Culture” by Marvin Harris (1989) Amazon.com;

“Domesticated: Evolution in a Man-Made World” by Richard C. Francis Amazon.com;

“Evolution of Domesticated Animals” by I. L. Mason | Jan 1, 1984 Amazon.com;

“The Cow: A Natural and Cultural History” by Professor Catrin Rutland (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Pig: A Natural History”by Richard Lutwyche (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Story of Garum: Fermented Fish Sauce and Salted Fish in the Ancient World”

by Sally Grainger (2020) Amazon.com;

“Piscinae: Artificial Fishponds in Roman Italy” by James Higginbotham (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Mariners: Seafarers and Sea Fighters of the Mediterranean in Ancient Times” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Water in the Roman World: Engineering, Trade, Religion and Daily Life”

by Jason Lundock and Martin Henig (2022) Amazon.com;

“A Cultural History of the Sea in Antiquity” by Marie-Claire Beaulieu (2024) Amazon.com;

“Food and Drink in Antiquity: A Sourcebook: Readings from the Graeco-Roman World” (Bloomsbury Sources in Ancient History) by John F. Donahue (2015) Amazon.com;

“Food in Roman Britain” by Joan P. Alcock (2001) Amazon.com;

“Farmers and Agriculture in the Roman Economy” by David B. Hollander (2018) Amazon.com;

“Roman Farming” by K. D. White (1970) Amazon.com;

“Agricultural Implements of the Roman World” by K. D. White (1967) Amazon.com;

“London's Roman Tools: Craft, Agriculture and Experience in an Ancient City” by Owen Humphreys (2021) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Development of the Roman Meat Diet

Roman meat market in Aquincum

Joel N. Shurkin wrote in insidescience: “Archaeologists studying the eating habits of ancient Etruscans and Romans have found that pork was the staple of Italian cuisine before and during the Roman Empire. Both the poor and the rich ate pig as the meat of choice, although the rich got better cuts, ate meat more often and likely in larger quantities. They had pork chops and a form of bacon. They even served sausages and prosciutto Angela Trentacoste of the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom specializes in the Etruscan civilization that preceded Rome in Italy. Much of her digging was in the tombs of rich Etruscans who often were buried with food and utensils. On some sites, she found 20,000 animal bones amid the rubbish. [Source: Joel N. Shurkin, insidescience, February 3, 2015 +/]

“As the hegemony of Rome grew so did the city and what was a largely rural Etruscan society became a more urban Roman one, she said. That changed the food supply. Most food, as now, came from farms outside the city. But, the city dwellers still raised pigs. They take up little room, can be easily bred and transported, Trentacoste said, and are easy to raise. +/

“They also had chickens roaming the yards that looked much like the chickens of today, MacKinnon said, and they were close to the same size. Modern farmers use breeding and nutrition to make the chickens grow faster, but eventually Roman chickens would catch up. Cattle take up too much room but rich Romans had beef occasionally, and sometimes goat. Low-fat food was not in vogue because the fat would protect meat from spoilage in a world without refrigerators.” +/

Early Domesticated Animals

The domestication of plants and animals took place around the same time. Hunter-gatherers and village horticulturists kept pets so they knew how to take care of animals. The domestication of animals took place when animals were raised as a source of food and labor. Grains were raised with the intent of feeding people and animals.

Some animals were domesticated so long ago that they have evolved as separate species. The process, some theorize, was as much accidental as intentional. With cats, for example, the anthropologist Richard Bullet suggests, the ancestors of cats were attracted to human settlements because they kept stores of grain that attracted mice they could fed on. Humans in turn tolerated the cats because they ate mice that fed on their grain and otherwise were not threatening.

Bullet as also theorized that horses, cattle and sheep were initially not domesticated for food but were domesticated for religious sacrifices. He argues it was more easy to hunt these animals than herd them and humans would have not gone through the trouble of keeping them unless they served some other purpose. He speculated that perhaps that unruly animals were sacrificed first to avoid trouble leaving more docile animals to mate and their offspring became increasingly tame.

RELATED ARTICLES: EARLY DOMESTICATED ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Livestock in Ancient Greece and Rome

horses working a millstone

in Roman times Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “Pigs were pastured in the oak groves to feed on the acorns. Varro advised keeping stock and game on all farms. Oxen were used for plowing, though that was slow work, but cattle-raising produced milk and cheese and beef. Sheep were valuable for the wool, to be worked by the women, as well as for the milk and cheese and meat. Where olives were grown, the sheep could be pastured on the grass in the groves. When the lowland pastures burned in the summer the flocks were driven to the hills. Goats were kept for the milk. The importance of pork has been mentioned, but it must be remembered that the Roman in general ate less meat than we do. Fowls were kept at the villa. Cato says that it is the business of the vilica to see that there are eggs in plenty. In addition to the chickens, geese, ducks, and guinea fowl familiar to us now, pigeons, thrushes, peafowl, and other birds were often raised for market. On some of the great estates game was bred in great variety. Bees were kept, of course, for honey was used where we use sugar. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Rabbits are believed to have been domesticated from wild rabbits from Iberia about in the Roman Era. The Greeks domesticated goats, dogs, horses, pigs, and sheep. Large horses first appeared in Greek times. Greeks developed the first horseshoes in the A.D. forth century. Sheep were raised for their fine wool.

Joel N. Shurkin wrote in insidescience: The Romans “also had chickens roaming the yards that looked much like the chickens of today, Michael MacKinnon, professor of archaeology at the University of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. MacKinnon said, and they were close to the same size. Modern farmers use breeding and nutrition to make the chickens grow faster, but eventually Roman chickens would catch up. Cattle take up too much room but rich Romans had beef occasionally, and sometimes goat. Low-fat food was not in vogue because the fat would protect meat from spoilage in a world without refrigerators.” [Source: Joel N. Shurkin, insidescience, February 3, 2015 +/]

Chickens were raised in Egypt and China for meat and eggs by 1400 B.C. Greeks ate them and they were in Britain at the time the Romans arrived. They were brought to New World by explorers and conquistadors. Chickens and other fowl were known to the Greeks. The expression "Don't count your chickens before they are hatched" is attributed to Aesop in 570 B.C. In the story The Milkmaid and her Pail , Patty the farmer's daughter says, "The milk in this pail will provide me with cream, which I will make into butter, which I will sell at the market, and buy a dozen eggs, and soon I shall have a large poultry yard. I'll sell some of the fowls and buy myself a handsome new gown."

Cattle were used for transportation purposes long before horses and figured prominently in many religions and myths (Hindu holy cows, the half-bull-half man Minotaur, the images of the Golden Calf that made Moses so angry). Bulls were sacrificed by the ancient Greeks, Romans and Druids but treated with reverence by Egyptians (black bulls in particular were given harems and palaces because they were believed to be related to the bull-god Apis).

Pigs in the Roman Era

pig being taken to a sacrifice

Pork was widely used by rich and poor alike, and was considered the choicest of all domestic meats. The very language testifies to the important place the pig occupied in the economy of the larder, for no other animal has so many words to describe it in its different functions. Besides the general term sus we find porcus, porca, verres, aper, scrofa, maialis, and nefrens. In the religious ceremony of the suovetaurilia (sus + ovis + taurus), the swine, it will be noticed, has the first place, coming before the sheep and the bull. The vocabulary describing the parts of the pig used for food is equally rich; there are words for no less than half a dozen kinds of sausages, for example, with pork as their basis. We read, too, of fifty different ways of cooking pork.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Joel N. Shurkin wrote in insidescience: “Archaeologists studying the eating habits of ancient Etruscans and Romans have found that pork was the staple of Italian cuisine before and during the Roman Empire. Both the poor and the rich ate pig as the meat of choice, although the rich got better cuts, ate meat more often and likely in larger quantities. They had pork chops and a form of bacon. They even served sausages and prosciutto. “As the hegemony of Rome grew so did the city and what was a largely rural Etruscan society became a more urban Roman one, she said. That changed the food supply. Most food, as now, came from farms outside the city. But, the city dwellers still raised pigs. They take up little room, can be easily bred and transported, Angela Trentacoste of the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom specializes in the Etruscan civilization that preceded Rome in Italy, said that pigs are easy to raise. [Source: Joel N. Shurkin, insidescience, February 3, 2015 +/]

Pigs are believed to have been domesticated from boars 10,000 years ago in Turkey, a Muslim country that ironically frowns upon pork eating today. At a 10,000-year-old Turkish archeological site known as Hallan Cemi, scientists looking for evidence of early agriculture stumbled across of large cache of pig bones instead. The archaeologists reasoned the bones came from domesticated pigs, not wild ones, because most of the bones belonged to males over a year old. The females, they believe, were saved so they could produce more pigs.

RELATED ARTICLE: PIGS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, PRODUCERS AND PORK-EATING CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com

Goats and Donkeys in Ancient Times

Goats have been around a long time. Mesopotamians wrote poems about goats, depicted them in golden sculptures, worshiped them as gods and made the goat-god Capricorn into a Zodiac sign. Goats have been taken all over the world to trade as sources of meat, wool and milk. Goats are mentioned in the Bible as well as in Buddhist, Confucian and Zoroastrian texts. In Greek myths, the gods were nursed on goats milk.

Donkeys were the first members if the horse family to be domesticated. They are believed to have been domesticated from wild asses, or onagers, from Arabia and North Africa about 6,000 years ago. See Assyria, Mesopotamia.

Onagers stand about 120 centimeters at the shoulder and weigh about 290 kilograms. They eat mostly sparse grasses and herbs that grow along desert edges. In the summer when water is scarce onagers survive by drinking salty water. Today onagers are threatened by loss of habitat, poaching and competition from grazing animals. About 800 onagers live in four remote desert areas of Iran.

Donkeys appeared in Egypt in the third millennium before Christ and are pictured on old Kingdom engravings dated to 2700 B.C., carrying people and loads in villages and urban areas. In the Old Testament the prophet Balaam was saved by a talking ass, who helped the prophet communicate with an angel he couldn't see. In the New Testament Jesus made his final entry into Jerusalem on one. In Roman times, Nero's wife is said to have bathed in donkey milk scented with rose oil.

RELATED ARTICLES: DONKEYS, MULES AND ONAGERS: THEIR HISTORY, USES AND BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com ; GOATS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, MILK AND MEAT factsanddetails.com ;

Donkey Milk and Goat Dung Energy Drink in Ancient Rome

Mark Oliver wrote for Listverse:“Romans didn’t have Band-Aids, so they found another way to patch up wounds. According to Pliny the Elder, people in Rome patched up their scrapes and wounds with goat dung. Pliny wrote that the best goat dung was collected during the spring and dried but that fresh goat dung would do the trick “in an emergency.” [Source: Mark Oliver, Listverse, August 23, 2016 +++]

“That’s an attractive image, but it’s hardly the worst way Romans used goat dung. Charioteers drank it for energy. They either boiled goat dung in vinegar or ground it into a power and mixed it into their drinks. They drank it for a little boost when they were exhausted. This wasn’t even a poor man’s solution. According to Pliny, nobody loved to drink goat dung more than Emperor Nero himself.” +++

“Donkey milk was hailed by the ancients as an elixir of long life, a cure-all for a variety of ailments, and a powerful tonic capable of rejuvenating the skin. Cleopatra, Queen of Ancient Egypt, reportedly bathed in donkey milk every day to preserve her beauty and youthful looks, while ancient Greek physician Hippocrates wrote of its incredible medicinal properties....Legend has it that Cleopatra (60 – 39 B.C.), the last active Pharaoh of Egypt, insisted on a daily bath in the milk of a donkey (ass) to preserve the beauty and youth of her skin and that 700 asses were need to provide the quantity needed. It was believed that donkey milk renders the skin more delicate, preserves its whiteness, and erases facial wrinkles. According to ancient historian Pliny the Elder, Poppaea Sabina (30 – 65 AD), the wife of Roman Emperor Nero, was also an advocate of ass milk and would have whole troops of donkeys accompany her on journeys so that she too could bathe in the milk. Napoleon’s sister, Pauline Bonaparte (1780–1825 AD), was also reported to have used ass milk for her skin’s health care. [Source:worldtruth.tv, February 1, 2015]

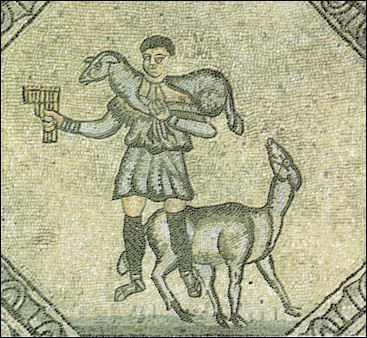

shepherd “Greek physician Hippocrates (460 – 370 B.C.) was the first to write of the medicinal virtues of donkey milk, and prescribed it as a cure a diverse range of ailments, including liver problems, infectious diseases, fevers, nose bleeds, poisoning, joint pains, and wounds. Roman historian Pliny the Elder (23 – 79 AD) also wrote extensively about its health benefits. In his encyclopedic work Naturalis Historia, volume 28, dealing with remedies derived from animals, Pliny added fatigue, eye stains, weakened teeth, face wrinkles, ulcerations, asthma and certain gynecological troubles to the list of afflictions it could treat: “Asses’ milk, in cases where gypsum, white-lead, sulphur, or quick-silver, have been taken internally. This last is good too for constipation attendant upon fever, and is remarkably useful as a gargle for ulcerations of the throat. It is taken, also, internally, by patients suffering from atrophy, for the purpose of recruiting their exhausted strength; as also in cases of fever unattended with head-ache. The ancients held it as one of their grand secrets, to administer to children, before taking food, a semisextarius of asses’ milk.”

Sheep, Wool, and Ancient History

Famous reference to wool and sheep from the ancient world include Jason's quest for the Golden Fleece, Ulysses escaping from the Cyclops by clinging onto the underbelly of a ram, and Penelope's nightly unraveling of her weaving to keep suitors away until Ulysses returned. Salome's veils may have been wool and Cleopatra most likely used a wool carpet to smuggle herself in to see Caesar."

There are a number of references to wool-damaging pests in the ancient world. The Romans used bare-breasted virgins to beat away moths and beetles that ate their wool garments. Other cultures tried cow manure and garlic. Now we use moth balls. Proper washing is also supposed to be affective discouraging moths.

There are 300 references to sheep and lambs, more than any other animal, in the Old Testament, one the earliest documents that mentions sheep. Abraham, Moses and David tended a sheep at one time to make a living. Jacob gave Joseph a multicolored coat and Roman's drew lots to see who would get Jesus's cloak. Both garments were probably made of wool. During biblical times fleece was left out overnight in the desert to collect drinking water. In the morning dew was wrung out of it. ╤

RELATED ARTICLES:

SHEEP: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS AND DOLLY factsanddetails.com

WOOL: HISTORY, TYPES, PROCESSING AND TRADE factsanddetails.com

Palladius: On Husbandry (c. A.D. 350)

Rutilius Taurus Aemilianus Palladius was a Roman writer from an élite family in Gaul who lived sometime between the late fourth and early fifth century of the common era. He is best known for his text on agriculture, De Re Rustica (Opus agriculturae).

Roman animal husbandry artifacts

“Book I, C.72. One should also take care about an oil-cellar; to warm it the pavement below should be perforated and raised. So that smoke cannot harm it, make a trench under the fire, and heat the well protected house from winter, keen and cold. Now I would like to write on the husbandry of stables. C.73. Toward the south you set the stable and the stall for horses and neats and get the light from the north, and close it tight to keep out the winter cold. In summer take care to cool the house and in the cold weather make a fire near the beasts; it will help the oxen and make them fair if they keep near the fire. [Source: : Palladius, On Husbandrie, translated by Barton Lodge, Early English Text Society, Vol. XXIV, No. 52, (London: N. Trubner, 1873-1879), reprinted in Roy C. Cave & Herbert H. Coulson, A Source Book for Medieval Economic History, (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Co., 1936; reprint ed., New York: Biblo & Tannen, 1965), pp. 38-41]

“C.108. Set the dunghill wet so it may rot and be odorless; also set it out of sight; the seed of thorn will decay and die in it. Assess dung is best to make a garden with; sheep's dung is next; and after that the goat's and neat's; also horses' and mares'; but swine's dung is the worst of all this lot. C.145. The bee-yard should not be far away but aside, clean, secret, and protected from the wind, square, and so strong that no thief can enter it.

“C.67. There must be marking irons for our beasts, and tools to geld, and clip, and shear; we also need leather coats to wear with hoods about our heads; and we must wear boots, leggings, mittens; all this is good for husbandmen and hunters; for they must walk in briars and in woods.

First Chickens in the West

Some of the earliest evidence of chickens being consumed as food in the West comes from Maresha, an ancient, abandoned city in Israel that flourished in the Hellenistic period from 400 to 200 B.C.. “The site is located on a trade route between Jerusalem and Egypt,” says Lee Perry-Gal, a doctoral student in the department of archaeology at the University of Haifa. As a result, it was a meeting place of cultures, “like New York City,” she says. [Source: Daniel Charles, NPR, July 20, 2015]

Daniel Charles of NPR wrote: “The surprising thing was not that chickens lived here. There’s evidence that humans have kept chickens around for thousands of years, starting in Southeast Asia and China. But those older sites contained just a few scattered chicken bones. People were raising those chickens for cockfighting, or for special ceremonies. The birds apparently weren’t considered much of a food.

In Maresha, though, something changed. The site contained more than a thousand chicken bones. “They were very, very well-preserved,” says Perry-Gal, whose findings appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Perry-Gal could see knife marks on them from butchering. There were twice as many bones from female birds as male. These chickens apparently were being raised for their meat, not for cockfighting.

See Separate Article: CHICKENS: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS AND DOMESTICATION europe.factsanddetails.com

Pompeii mosaic of cockfighting

Roman Fishing and Tuna Traps

Romans ate lobster, crab, octopus, squid, cuttlefish, mullet, sea urchins, scallops, clams, mussels, sea snails, tuna, sea bream, sea bass and scorpion fish. They liked to cook fish live at the table and the Senate once debated the proper way to serve the first turbot. Hadrian was fond of salmon rolled with caviar. Fresh oysters were very popular. They were brought to Rome from Breton in modern-day France by runners in around 24 hours.

Fishermen have been catch bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean for more than 3,000 years. Using a technique that has been employed since Roman times, fishermen in southern Spain and Italy set up fixed trap nets known as “almadradas “ in Spanish and “tonnara “ in Italian — a labyrinth of nets anchored in shallow waters near the coast that funnels fish into chambers, where they were slaughtered. [Source: Fen Montaigne, National Geographic, April 2007]

In the mid 1800s around a hundred of these tuna traps harvested up to 15,000 tons of bluefin annually. The fishery was sustainable, supporting thousands of workers and their families. Today all but a dozen or so have been closed because of coastal development, pollution and overfishing. One of the last remaining ones that is open was built by Arabs in the 9th century on the island of Favignana of Sicily. In 1864 fisherman there caught a record 14,020 bluefin, averaging 425 pounds. In 2006, they caught around 100 fish, averaging 65 pounds. That year only one “mattanza” — in which the tuna and channeled into a netted chamber and slaughtered at the surface by fishermen who kill them with gaffs — was held. There are now plans to dress fishermen in historic costumes and reenact the mattanza.

RELATED ARTICLES:

GARUM FISH SAUCE AND SPICES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

MEAT AND SEAFOOD IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Roman Whaling?

A study published in 2019 using advanced technology was able to identify the bones of both the North Atlantic right whale and the gray whale from a handful of Roman sites around the Strait of Gibraltar. Southern Iberia was once home to a thriving Roman fish-processing industry. Although these whale species no longer frequent these waters, researchers argue that around 1,500 to 2,000 years ago, they would have been prevalent in the western Mediterranean and were likely hunted by Roman fishermen. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2018]

Nicola Davis wrote in The Guardian> Writing in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Rodrigues and a team of archaeologists and ecologists, describe how they set out to unpick the issue by examining 10 bones — thought to be from whales — collected during recent archaeological digs or housed in museum collections. These bones came from five sites — four around the Strait of Gibraltar and one site on the coast of north-west Spain, three of which were linked to the Roman fish-salting and fish-sauce making industries. The team combined previous anatomical analysis with new analyses based both on DNA extracted from the bones and their collagen — a protein whose makeup differs between groups of species, and which degrades more slowly than DNA.[Source Nicola Davis, The Guardian, July 10, 2018]

While one of the bones was found to be from a dolphin and another from an elephant — possibly a war animal — three were identified as grey whales, and two as North Atlantic right whales with another also suspected of being from this latter species. All were found by carbon-dating as being from either Roman or pre-Roman times — findings backed up by dating based on information from the archaeological sites.

The team say the discovery suggests grey and North Atlantic right whales were common in the waters around the Strait of Gibraltar during Roman times, since whale bones rarely end up in the archaeological record and they are not prized possessions. This theory is backed up by writings from the time: Pliny the Elder — a fervent naturalist who died down the coast from Pompeii during the volcanic disaster — appears to reference whales calving in the coastal waters off Cadiz in the winter in his Naturalis Historia. And if the whales were present, the team say, it is possible the Romans hunted them.

The team say the location of the bones, and other evidence, suggests whales might even have entered further into the Mediterranean sea itself to calve. Dr Vicki Szabo, an expert in whaling history from Western Carolina University said the study offered a rare glimpse into the past habitats of the whales, and backed up ideas that industrial hunting might have happened far earlier than widely thought, although its scale is unclear. “Whales are considered archaeologically invisible because so few bones are transported from shore to site, so I think in that context this concentration of species that they have is meaningful,” she said.

Mark Robinson, professor of environmental archaeology at the University of Oxford, said there have been suggestions for a decade that some Roman sites with fish vats in the region might have been linked to whaling. “The Greek author Oppian, writing in the 2nd century AD, describes whales being hunted in the Western Mediterranean by harpooning them on the surface, also using tridents and axes to kill them, lashing them to a boats and then dragging them to the shore.”

However Dr Erica Rowan, a classical archaeologist at Royal Holloway, University of London, said while the study suggests the habitats of the whales probably extended to include the Gibraltar region, how common the whales were and whether the Romans industrially hunted them as they did fish such as tuna remains unclear — not least because the study included just a handful of bones from a period spanning several hundred years.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024