CROPS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE

wheat

Major crops included grapes, olives, figs, pears, apples, peaches, cherries, plums and walnuts. Romans grafted apple trees and spread apple cultivation throughout their empire. Grain was grown on vast North African estates nourished with irrigated water from small dammed reservoirs and worked by slaves. But as as time went on the productivity of Africa declined. One writer wrote: "North Africa's rich granaries that once fed the Roman Empire have vanished. Tunisia has lost perhaps half its arable land. Algeria is planting a green belt of trees to keep the desert away, and there has been talk or ringing most of the Sahara with such a living Maginot line.

The Roman farmer understood something of seed selection and practiced rotation of crops. He followed wheat with rye, barley, or oats. The second or fourth year beans or peas might be planted, sometimes to be plowed under green as stated above, or alfalfa was put in. Alfalfa (medica) was well established in Italy before the beginning of our era; according to Pliny the Elder, it was brought from Greece, having come there from Asia. In other cases the land was left fallow every second or third year. Sometimes it was left fallow the year before wheat was planted. It was then plowed in the spring and summer as well as in the fall. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Cato lists farm crops in the order of their importance in his time. First he puts the vineyard, then the vegetable garden, willow copse, olive grove, meadow, grain fields, wood lot, orchard, and oak grove. It is to be noted that he puts grain in the sixth place. The transportation problem was also a factor here, for, as moving grain overland was difficult and expensive, it was cheaper to import it from the provinces by sea. Vine-growing has been discussed in detail, as have the growing of the olive and processes pertaining to it. |+|

“The vegetables grown by the Romans and their importance in the diet have been mentioned . The farm garden contained the commonest of these for home consumption, with herbs for seasoning and for the home remedies, bee plants, and garland flowers. These last were not for garlands at banquets, unless the farm lay near a town and they were grown for sale, but for garlands to deck the hearth in honor of the household gods on festival days. Near the towns market-gardening was profitable, and vegetables, fruits, and flowers were grown. In early days a garden had lain behind each house, and the excavations at Pompeii show occasional traces of small gardens even behind large town houses. |+|

“Wheat was sown in the fall and cultivated by hand with the hoe in the spring. At harvest time it was generally cut by hand. Sometimes the reapers cut close to the ground, and after the sheaves were piled in shocks cut off the heads for the threshing. Sometimes they cut the heads first and the standing straw later. There was a simple form of a header pushed by an ox, but this could be used only where the ground was level. Threshing was done by hand on the threshing floor, or the grain was trodden out by cattle, or beaten out by a simple machine. It was winnowed by hand, by the process of tossing it in baskets, or by shovels so that the chaff flew out or away. |+|

“Reeds and willows were planted in damp places. Willows were useful for baskets, ties for vines, and other farm purposes. The wood made a quick, hot fire in the kitchen. Vergil knew the willow as a hedge plant, whose early blossoms were loved by the bees. The word arbustum, translated by the word “orchard,” does not refer to an orchard as we understand the term, but to regular rows of trees, elm, poplar, fig, or mulberry, planted for the training of vines, with grass, alfalfa, or vegetables between.

RELATED ARTICLES:

AGRICULTURE IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

FARMING AND RURAL LIFE IN THE ROMAN ERA factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN LIVESTOCK AND FISHING: PIGS, TUNA AND WHALES? factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Rome Olive Guide: Olive Trees, Fruit, Oil & Recipes” by Pliny, Columella, et al. | (2021) Amazon.com;

“Roman and Late Antique Wine Production in the Eastern Mediterranean: A Comparative Archaeological Study at Antiochia ad Cragum (Turkey) and Delos (Greece)” by Emlyn Dodd | (2020) Amazon.com;

“Wine in Ancient Greece and Cyprus: Production, Trade and Social Significance”

by Evi Margaritis, Jane M. Renfrew, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“From Vines to Wines in Classical Rome” by David L. Thurmond (2016) Amazon.com;

“Food and Drink in Antiquity: A Sourcebook: Readings from the Graeco-Roman World” (Bloomsbury Sources in Ancient History) by John F. Donahue (2015) Amazon.com;

“Food in Roman Britain” by Joan P. Alcock (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Grain Market in the Roman Empire: A Social, Political and Economic Study”

by Paul Erdkamp (2005) Amazon.com;

“Farmers and Agriculture in the Roman Economy” by David B. Hollander (2018) Amazon.com;

“Bringing in the Sheaves: Economy and Metaphor in the Roman World”

by Brent Shaw (2015) Amazon.com;

“Roman Farming” by K. D. White (1970) Amazon.com;

“Agricultural Implements of the Roman World” by K. D. White (1967) Amazon.com;

“London's Roman Tools: Craft, Agriculture and Experience in an Ancient City” by Owen Humphreys (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Agricultural Economy: Organization, Investment, and Production”

by Alan Bowman and Andrew Wilson (2013) Amazon.com;

“Cato: On Farming - De Agricultura” by Cato, translated by Andrew Dalby Amazon.com;

“Roman Farm Management The Treatises of Cato and Varro”, translated by Fairfax Harrison (1869-1938) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Ancient Agriculture (Blackwell) by David Hollander and Timothy Howe (2020) Amazon.com;

“Agricola; a Study of Agriculture and Rustic Life in the Greco-Roman World From the Point of View of Labour: by William Emerton Heitland (1847-1935) Amazon.com;

“The Culture of Animals in Antiquity” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones and Sian Lewis (2020) Amazon.com;

“Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity” by Thorsten Fögen and Edmund V. Thomas (2017) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2017) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Common Foods in the Roman Empire

ancient roman pigeon house

Among other things Romans ate doves, chickens, figs, dates, olives, grapes, white almonds, truffles and fois gras and cooked fowl in clay pots. There were no tomatoes, potatoes, spaghetti, risotto, or corn. Romans often turned up their noses at the food from outside Rome. On the food in Greece a character in a satire commented: “They give weeds to their guests, as though they were cattle. And they flavor their weeds with other weeds."

The Romans consumed dairy products such as milk, cream, curds, whey, and cheese. They drank the milk of sheep and goats as well as that of cows, and made cheese of the three kinds of milk. The cheese from ewes’ milk was thought more digestible, though less palatable, than that made from cows’ milk, while cheese from goats’ milk was more palatable but less digestible. It is remarkable that they had no knowledge of butter except as a plaster for wounds. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Honey took the place of sugar on the table and in cooking, for the Romans had only a botanical knowledge of the sugar cane. Salt was at first obtained by the evaporation of sea water, but was afterwards mined, Its manufacture was a monopoly of the government, and care was taken always to keep the price low. It was used not only for seasoning, but also as a preservative agent. Vinegar was made from grapes. Among the articles of food unknown to the Romans were tea and coffee, along with the orange, tomato, potato, butter, and sugar.” |+|

RELATED ARTICLE: FOOD IN ANCIENT ROME: STAPLES, EXOTIC DISHES, PIZZA

Grains and Cereals in Ancient Rome

Grain was the main commodity in ancient Rome. It was used to make bread and porridge, the staples of the Roman diet. Poor people subsisted on a gruel-like soup of mush made from grain. The Roman grain goddess Ceres gave birth to the word "cereal." Chickpeas, emmer wheat and lentils were all eaten. Rice was imported from India and used as a medicine.

The word frumentum was a general term applied to any of the many sorts of grain that were grown for food. The word frumentum occurs fifty-five times in Caesar’s Gallic War, meaning any kind of grain that happened to be grown for food in the country in which Caesar was campaigning at the time. Of those now in use barley, oats, rye, and wheat were known to the Romans, though rye was not cultivated, and oats served only as feed for cattle. Barley was not much used, for it was thought to lack nutriment, and therefore to be unfit for laborers. In very ancient times another grain, spelt (far), a very hardy kind of wheat, had been grown extensively, but it had gradually gone out of use except for the sacrificial cake that had given its name to the confarreate ceremony of marriage. In classical times wheat was the staple grain grown for food, not differing much from that which we have today. It was usually planted in the fall, though on some soils it would mature as a spring wheat. After grain ceased to be much grown in Central Italy and the land was diverted to other purposes, wheat had to be imported from the provinces, first from Sicily, then from Africa and Egypt, as the home supply became inadequate to the needs of the teeming population. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

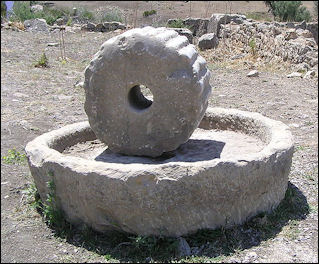

emmer“Preparation of the Grain. In the earliest times the grain (far) had not been ground, but had been merely pounded in a mortar. The meal was then mixed with water and made into a sort of porridge (puls, whence our word “poultice”), which long remained the national dish something like the oatmeal of Scotland. Plautus (died 184 B.C.) jestingly refers to his countrymen as “pulse-eaters.” The persons who crushed the grain were called pinsitores, or pistores, whence the cognomen Piso, as was said above, was derived; in later times the bakers were also called pistores, because they ground the grain as well as baked the bread. In the ruins of bakeries we find mills as regularly as ovens. |+|

“In such mills the grain was ground into regular flour. The mill (mola) consisted of three parts, the lower millstone (meta), the upper stone (catillus), and the framework that surrounded and supported the latter and furnished the means to turn it upon the meta. The meta was, as the name suggests, a cone shaped stone (A) resting on a bed of masonry (B) with a raised rim, between which and the lower edge of the meta the flour was collected. In the upper part of the meta a beam (C) was mortised, ending above in an iron pin or pivot (D), on which hung and turned the framework that supported the catillus. The catillus (E) itself was shaped something like an hourglass, or two funnels joined at their necks. The upper funnel served as a hopper into which the grain was poured; the lower funnel fitted closely over the meta. From a relief in the Vatican Museum, Rome.The distance between the lower funnel and the meta was regulated by the length of the pin, mentioned above, according to the fineness of the flour desired. |+|

RELATED ARTICLE: BREAD IN ANCIENT ROME: GRAINS, MILLING AND PRISON-BAKERIES europe.factsanddetails.com

“The framework was very strong and massive on account of the heavy weight that was suspended from it. The beams used for turning the mill were fitted into holes in the narrow part of the catillus. The power required to do the grinding was furnished by horses or mules pulling the beams, or by slaves pushing against them. This last method was often used as a punishment, as we have seen. Of the same form but much smaller were the hand mills used by soldiers for grinding the frumentum furnished them as rations. Under the Empire, water mils were introduced, but they are rarely mentioned in literature.” |+|

Fruits and Vegetables in the Roman Empire

The Greco-Romans grew and ate tangerines, oranges, lemons, olives, figs, grapes, pears, apples, often in poor soils. Romans grafted apple trees and spread apple cultivation throughout their empire.The apple, pear, plum, and quince were either native to Italy or, like the olive and the grape, were introduced into Italy long before history begins. Careful attention had long been given to their cultivation, and by Cicero’s time Italy was covered with orchards. All these fruits were abundant and cheap in their seasons, and were used by all sorts and conditions of men. By Cicero’s time, too, had begun the introduction of new fruits from foreign lands and the improvement of native varieties. Great statesmen and generals gave their names to new and better sorts of apples and pears, and vied with one another in producing fruits out of season by hothouse culture. Every fresh extension of Roman territory brought new fruits and nuts into Italy. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Among the fruits the peach (malum Persicum), the apricot (malum Armeniacum), the pomegranate (malum Punicum or granatum), the cherry (cerasus, brought by Lucullus from the town Cerasus in Pontus), and the lemon (citrus, not grown in Italy until the third century of our era). Similarly, the fruits, grains, and vegetables known at home were carried out through the provinces wherever the Romans established themselves. Cherries, for instance, are said to have been grown in Britain in 47 A.D., four years after its conquest. Besides the introduction of fruits for culture, large quantities, either dried or otherwise preserved, were imported for food. The orange, however, strange as this seems to us, was not grown by the Romans. Fresh vegetables, and fresh fruits could not be brought from great distances.” |+|

The Greco-Romans grew and ate cabbage, leeks, onions, chick peas, beans and turnips, often in poor soils. The garden did not yield to the orchard in the abundance and variety of its contributions to the supply of food. We read of artichokes, asparagus, beans, beets, cabbage, carrots, chicory, cucumbers, garlic, lentils, melons, onions, peas, the poppy, pumpkins, radishes, and turnips, to mention only those whose names are familiar to us all. It will be noticed, however, that the vegetables perhaps most prized by us, the potato and the tomato, were not known to the Romans. Of those mentioned the oldest seem to have been the bean and the onion, as shown by the names Fabius and Caepio already mentioned, but the latter came gradually to be looked upon as unrefined and the former to be considered too heavy a food except for persons engaged in the hardest toil. Cato pronounced the cabbage the finest vegetable known, and the turnip figures in the well-known anecdote of Manius Curius. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

RELATED ARTICLE: OLIVES, FRUITS AND VEGETABLES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Olives

Olive press in Pompeii Olives and olive oil were staples in ancient Greece and Rome. Olives were used as food and fuel as well as a trade commodity. Sophocles called olives "our sweet silvered wet nurse." Olives were valued more as a source of fuel for oil lamps than as a food. They were also used to make soap. Olives were regarded as so precious that killing an olive tree was sometimes punished by death.

Olives are fruit that comes from a gnarled tree and are still a staple of the Mediterranean diet. People eat them for meals and snacks, and use olive oil for cooking and to dip bread in. Olives come in a host of colors and textures: salty, wrinkled and black, oily and green, and even massive and purple. Italy alone is home to 60 different types of olive tree. [Source: Dora Jane Hamblin, Smithsonian; Erla Zwingle, National Geographic, September 1999]

The olive is a drupe, or stone fruit, like a plum or cherry. Olives start out green and very bitter and turn black when they mature. Eating a bitter olive raw off a tree is like eating "an unplucked chicken or an uncooked potato." Different varieties of olives are usually picked at different points in the development of the fruit. Green olives generally have more Vitamin E and less oil than black olives, which have a stronger flavor and more oil. Most green olives are eaten whole rather than made into oil. Only 10 percent of the olive crop is eaten as food. Most olives are made into oil.

See Separate Article OLIVES: OIL, HISTORY, PRODUCTION AND SCAMS factsanddetails.com

Book: “Olives, the Life and Love of a Noble Fruit” by Mort Rosenblum (North Point/ Farrar Straus Giroux).

Olives and Olive Oil in the Roman Era

In the Roman Empire olive oil was a major cash crop. Consumption by individuals rose to as much as 50 liters a year and some families grew quite rich trading it. In many ways olive oil was valued as much in ancient times as petroleum is today, with governments going to great lengths to make sure there was a steady supply. Some emperors gave it out free to the masses as part of their bread and circuses policy. The main pieces of farm machinery were olive oil presses.

Olives were the most important crop in the Roman Empire after wheat. They introduced into Italy from Greece, and from Italy has spread through all the Mediterranean countries; but in ancient times the best olives were those of Italy, even as today the best olives come from Italy. The olive was an important article of food merely as a fruit. It was eaten both fresh and preserved in various ways, but it found its significant place in the domestic economy of the Romans in the form of the olive oil with which we are familiar. It is the value of the oil that has caused the cultivation of the olive to become so general in southern Europe. Many varieties of the olive were known to the Romans; they required different climates and soils and to were adapted to different uses. In general it may be said that the larger fruit were better suited for eating than for oil. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

olive picking

“The olive was eaten fresh as it ripened and was also preserved in various ways. The ripe olives were sprinkled with salt and left untouched for five days; the salt was then shaken off, and the olives dried in the sun. They were also preserve sweet without salt in boiled must. Half-ripe olives were picked with their stems and covered over in jars with the best quality of oil; in this way they are said to have retained for more than a year the flavor of the fresh fruit. Green olives were preserved whole in strong brine, the form in which we know them now, or were beaten into a mass and preserved with spices and vinegar. The preparation called epityrum was made by taking the fruit in any of the three stages, removing the stones, chopping up the pulp, seasoning it with vinegar, coriander seeds, cumin, fennel, and mint, and covering the mixture in jars with oil enough to exclude the air. The result was a salad that was eaten with cheese.” |+|

Olive oil was used for several purposes. It was employed at first to anoint the body after bathing, especially by athletes; it was used as a vehicle for perfumes (the Romans knew nothing of distillation by means of alcohol); it was burned in lamps; it was an indispensable article of food. As a food it was employed in its natural state as butter is now in cooking, or in relishes, or dressings. The olive when subjected to pressure yields two fluids. The first to flow (amurca) is dark and bitter, having the consistency of water. It was largely used as a fertilizer, but not as a food. The second, which flows after greater pressure, is the oil (oleum, oleum olivum). The best oil was made from olives not fully ripe, but the largest quantities was yielded by the ripened fruit.”

Olive Agriculture the Roman Empire

The olives were picked from the tree; those that fell of their own accord were thought inferior and were spread upon sloping platforms in order that a part of the amurca might flow away by itself. Here the fruit remained until a slight fermentation took place. It was then subjected to the action of a machine that bruised and pressed it to separate the pulp from the stones. The pulp was then crushed in a press. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Roman olive pressThe oil that flowed out” of the love presses “was caught in a jar and from it ladled into a receptacle (labrum fictile), where it was allowed to settle; the amurca and other impurities went to the bottom. The oil was then skimmed off into another like receptacle and again allowed to settle; the process was repeated (as often as thirty times if necessary) until all impurities had been left behind. The best oil was made by subjecting the olives at first to a gentle pressure only. The bruised pulp was then taken out, separated from the stones or pits, and pressed a second or even a third time, the quality becoming poorer each time. The oil was kept in jars which were glazed on the inside with wax or gum to prevent absorption; the covers were carefully secured and the jars stored away in vaults. In the old days the presses were powered by donkeys, camels, cattle and mules and later steam. Today they are mainly driven by electricity. In Tunisia olive oil is still made from camel-driven presses.

Olive Production in Tunisia Crashed Because Roman Iron Production

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology Magazine: After the Romans conquered the Phoenicians of northern Africa in 146 B.C., they allowed them to maintain their cultural traditions, but imposed a new economic system. The drastic cost of this was evident at Zita, a city in present-day Tunisia that was once famous for its olive groves. A team of American researchers and archaeologists from Tunisia’s National Heritage Institute compared the quantity of iron slag and carbonized olive pits in soil from the city’s iron smelting workshops. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2022]

When the Romans took over, they increased iron production, but the problems didn’t begin until about A.D. 200. “We can see clearly in the archaeological record that they lost the balance between producing fuel and producing olive oil,” says archaeologist Brett Kaufman of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He believes that plagues and political instability may have created economic pressures that led to shortsighted decisions. To feed Rome’s appetite for iron, the olive orchards that had sustained Zita’s economy for centuries were fed into the smelting furnaces, leading to the city’s collapse around A.D. 450. “It’s just shocking to think about the emotional cost for the people who realized that they were feeding an empire and losing their own city in the process,” says Kaufman.

Grapes, Vineyards and Viticulture in the Roman Era

Grapes were eaten fresh from the vines and were also dried in the sun and kept as raisins, but they owed their real importance in Italy as elsewhere to the wine made from them. It is believed that the grapevine was not native to Italy, but was introduced, probably from Greece, in very early times. The first name for Italy known to the Greeks was Oenotria, a name which may mean “the land of the vine”; very ancient legends ascribe to Numa restrictions upon the use of wine. It is probable that up to the time of the Gracchi wine was rare and expensive. The quantity produced gradually increased as the cultivation of cereals declined, but the quality long remained inferior; all the choice wines were imported from Greece and the East. By Cicero’s time, however, attention was being given to viticulture and to the scientific making of wines, and by the time of Augustus vintages were produced that vied with the best brought from abroad. Pliny the Elder says that of the eighty really choice wines then known to the Romans two-thirds were produced in Italy; and Arrian, about the same time, says that Italian wines were famous as far away as India. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Grapes could be grown almost anywhere in Italy, but the best wines were made south of Rome within the confines of Latium and Campania. The cities of Praeneste, Velitrae, and Formiae were famous for the wine grown on the sunny slopes of the Alban hills. A little farther south, near Terracina, was the ager Caecubus, where was produced the Caecuban wine, pronounced by Augustus the noblest of all. Then came Mt. Massicus with the ager Falernus on its southern side, producing the Falernian wines, even more famous than the Caecuban. Upon and around Vesuvius, too, fine wines were grown, especially near Naples, Pompeii, Cumae, and Surrentum. Good wines, but less noted than these, were produced in the extreme south, near Beneventum, Aulon, and Tarentum. Of like quality were those grown east and north of Rome, near Spoletium, Caesena, Ravenna, Hadria, and Ancona. Those of the north and west, in Etruria and Gaul, were not so good. |+|

“The sunny side of a hill was the best place for a vineyard. The vines were supported by poles or trellises in the modern fashion, or were planted at the foot of trees up which they were allowed to climb. For this purpose the elm (ulmus) was preferred, because it flourished everywhere, could be closely trimmed without endangering its life, and had leaves that made good food for cattle when they were plucked off to admit the sunshine to the vines. Vergil speaks of “marrying the vine to the elm,” and Horace calls the plane tree a bachelor (platanus caelebs), because its dense foliage made it unfit for the vineyard. Before the gathering of the grapes the chief work lay in keeping the ground clear; it was spaded over once each month in the year. One man could properly care for about four acres.” |+|

In 2012, Nancy Thomson de Grummond of Florida State University announced that she had discovered some 150 waterlogged grape seeds in a well in Cetamura del Chianti Italy and probably date to about the A.D. 1st century. There is possibility the seeds’ DNA can analyzed. The seeds could provide “a real breakthrough” in the understanding of the history of Chianti vineyards in the area, de Grummond said. “We don’t know a lot about what grapes were grown at that time in the Chianti region.“Studying the grape seeds is important to understanding the evolution of the landscape in Chianti. There’s been lots of research in other vineyards but nothing in Chianti.” [Source: Elizabeth Bettendorf, Phys.org, December 6, 2012] Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024