TRADE IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE

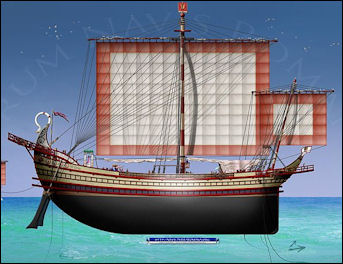

Roman transport ship The Roman established wide trade network across the Mediterranean. Ships regularly crossed the open Mediterranean out of site of land from Italy to Carthage in Northern Africa. There were Flame-toped lighthouses like the Pharos Lighthouse in Alexandrian, one of the Seven Wonders of the World. River travel could be quite slow. The 600-mile, up-river boat journey on the Nile from Alexandria to Coptos (now Qift) took two weeks even when the boat traveled day and night.

Important trade items included metals and olive oil from Spain and Africa, grain from Egypt, Africa and the Crimea, spices and silks from the east and wine from France and Italy. They were carried in large jug-like red clay amphoras on square-sailed merchant ships. Ivory from Africa, silk from China, spices, pepper and cotton from India, wheat, and linen and marble from Egypt were carried by ships across the Mediterranean. The amphorae used to transport oil, wine and other foodstuffs were generally about five feet high.

By the 2nd century, the Romans had a well developed trade network with China. Silks, rich brocades, cloth of gold and jeweled embroideries made their way to Rome from China and Persia. Caravans loaded with perfumes from Arabia, spices and rare woods from India, and silk from China passed through Palmyra in Syria and other oasis towns and made their way to the Roman Empire. along what would later be called the Silk Road

RELATED ARTICLES:

ECONOMY OF ANCIENT ROME: GRAIN, SUBSIDIES, INFLATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MONEY IN ANCIENT ROME: HISTORY, COINS, DEBASEMENT europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BUSINESSES IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

INDUSTRIES IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

MINING AND RESOURCES IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Trade, Transport and Society in the Ancient World: A Sourcebook” (Routledge Revivals) by Onno Van Nijf and Fik Meijer (2014) Amazon.com;

“Trade-Routes and Commerce of the Roman Empire” by M.P. Charlesworth (1926) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Empire and the Wider World: The Two-Way Trade of Goods, Culture, Knowledge and Religion” by Paul Chrystal (2025) Amazon.com;

“Production, Trade, and Connectivity in Pre-Roman Italy (Routledge) by Jeremy Armstrong and Sheira Cohen (2022) Amazon.com

“The Romans and Trade” by Andre Tchernia (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Open Sea: The Economic Life of the Ancient Mediterranean World from the Iron Age to the Rise of Rome” by J. G. Manning (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Economics of the Roman Stone Trade” by Ben Russell (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Bazaar: A Comparative Study of Trade and Markets in a Tributary Empire” by Peter Fibiger Bang (2009) Amazon.com;

“Wine in Ancient Greece and Cyprus: Production, Trade and Social Significance”

by Evi Margaritis, Jane M. Renfrew, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Amphoras and the Ancient Wine Trade” by Virginia R. Grace (1980) Amazon.com;

“Rivers and the Power of Ancient Rome” by Brian Campbell (2012) Amazon.com;

“Travel and Geography in the Roman Empire” by Colin Adams and Ray Laurence (2011) Amazon.com;

“Water in the Roman World: Engineering, Trade, Religion and Daily Life”

by Jason Lundock and Martin Henig (2022) Amazon.com;

“A Cultural History of the Sea in Antiquity” by Marie-Claire Beaulieu (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (1995) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Boats and Ships” by Sean McGrail (2008) Amazon.com;

“Marine Craft in Ancient Mosaics of the Levant” by Eva Grossmann (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Port of Roman London” by Gustav Milne (1985) Amazon.com;

“Roman Port Societies: The Evidence of Inscriptions’ by Pascal Arnaud and Simon Keay (2020) Amazon.com;

“Ostia Speaks: Inscriptions, Buildings and Spaces in Rome's Main Port” by LB van der Meer (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Commerce Between the Roman Empire and India”, by E. H Warmington (1928) Amazon.com;

“Worlds Apart Trading Together: the Organisation of Long-distance Trade Between Rome and India in Antiquity” (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Commerce And Navigation Of The Erythraean Sea” by Flavius Arrianus Amazon.com;

“Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route” by Steven E. Sidebotham (2019)

Amazon.com;

“The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: The Ancient World Economy & the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia & India” by Raoul McLaughlin (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes: The Ancient World Economy and the Empires of Parthia, Central Asia and Han China” by Raoul McLaughlin (2016) Amazon.com;

Extensiveness of Roman Foreign Trade

J. A. S. Evans wrote: Foreign trade was extensive. The Romans imported amber from the Baltic Sea, slaves, hides, timber for shipbuilding, hemp, wax and pitch from northern and eastern Black Sea ports, frankincense from Yemen, spices from India, and silk from China. Much of the silk was imported via India and followed a route from Indian ports up the Persian Gulf and from there by caravan to Mediterranean ports, but there was an alternative silk route from China to Black Sea ports in the Crimea. Roman mariners discovered the monsoons towards the end of the first century, and convoys of merchantmen began to sail directly from Red Sea ports to Sri Lanka and India. Fairs, both regional and local, assumed great importance in foreign trade, particularly in Late Antiquity, for merchants would come to these fairs, which were held periodically, to buy and sell their goods there. It has been argued that an unfavorable trade balance with the east drained the empire's gold supply, but the evidence is slight. Many Roman gold coins have been found in India; silver denarii up to the time of Nero have also been found, but after Nero debased the denarius it was no longer accepted in India. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Into Rome's three ports of Ostia, Portus, and the emporium beneath the Aventine poured the tiles and bricks, the wines and fruits of Italy; the grain of Egypt and Africa; the oil of Spain; the venison, the timbers, and the wool of Gaul; the cured meats of Baetica; the dates of the oases; the marbles of Tuscany, of Greece, and of Numidia; the porphyries of the Arabian Desert; the lead, silver, and copper of the Iberian Peninsula; the ivory of the Syrtes and the Mauretanias, the gold of Dalmatia and of Dacia; the tin of the Cassiterides, now the Scilly Isles, and the amber of the Baltic; the papyri of the valley of the Nile; the glass of Phoenicia and of Syria; the stuffs of the Orient; the incense of Arabia; the spices, the corals, and the gems of India; the silks of the Far East. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

In the city and its suburbs the sheds of the warehouses (horrea) stretched out of sight. Here accumulated the provisions that filled Rome's belly, the stores that were the pledge of her well-being and of her luxury. The excavations undertaken in 1923 by the late Prince Giovanni Torlonia have revealed the importance of the horrea of the Portus of Trajan; though only onethird of the area covered in Hadrian's day by the horrea of Ostia has so far been excavated, they already cover some ten hectares. The discovery of the ancient Roman horrea, the number and extent of which are indicated in the literature of the time, has in fact only been begun. 18 Some of these specialised in a single type of goods: the horrea candelaria stored only torches, candles, and tallow; the horrea chart aria on the Esquiline were consecrated to rolls of papyrus and quires of parchment; while the horrea piperataria near the Forum were piled with the supplies of pepper, ginger, and spices convoyed there by the Arabs.

Augustus and Roman Trade

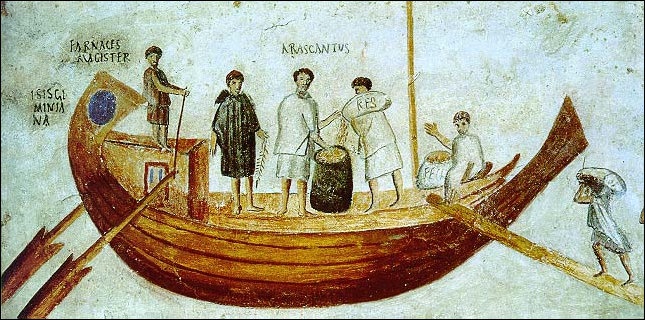

Greek trading ship

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Augustus, who became emperor in 27 B.C., knew that his power base came from two sources — the army and the plebs, or common people. He also understood that the needs of a growing population of Rome (between 600,000 and one million in the first century A.D.), along with a massive army stationed along frontiers from Spain to Syria, demanded a sophisticated and complex system to transport food and raw materials between Rome and its provinces. The emperor ensured the army’s support by paying and feeding it. He likewise bought the plebians’ loyalty by continuing the tradition, established in the mid-first century B.C., of providing them with access to free grain and by subsidizing the price of olive oil much like the current state-regulated price of tortillas in Mexico or baguettes in Tunisia. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2015]

More than a century after Augustus, the Roman satirist Juvenal would give lasting expression to this populist approach in the famous line about the emperor giving the Romans “bread and circuses” in exchange for their freedom. To administer these needs, Augustus set up the praefectura annonae, or “prefect of the provisions,” an office whose function remains hotly debated. Some scholars believe the annona only handled the grain distribution for the plebs. But Remesal argues that the office served all of Rome’s inhabitants and dealt with many products, including olive oil.

“From Augustus’s time, olive oil amphoras from Baetica in Spain are found at Monte Testaccio and as far as the northern borders of the empire, in the provinces of Brittania and Retia [parts of Austria and Germany],” he says. “I don’t think this could have happened without the emperor being directly involved.” But how far-reaching was this so-called “command economy,” the state-driven system controlled by the empire that brought olive oil to Rome and the amphoras to Monte Testaccio? University of Southampton archaeologist Simon Keay, who directs a major survey project at Portus, says, “The imperial finger is clearly on the pulse and they are very closely controlling and monitoring everything, but it’s not heavily bureaucratic. Rather, this is a system of small suppliers who are well controlled and monitored, not a system of great trade routes like other empires have had. It is uniquely Roman.”

How Ancient Roman Trade Was Carried Out

Traders obtained the finances they needed to buy commodities through maritime loans, in which the cargo was pledged as a security and interest payments were around 30 percent. If the cargo showed up the trade could pay off the loan and still make a huge profits. The loan was only repaid after the cargo arrived. If the ship didn't make it the financiers of the loan lost their money not the trader. Even under these terms, investors were willing to take the risk because such trading was one of the few ways that someone could rich quick. If they ship did come in more often than not the cargo could be sold for three or four times the price that as payed for the cargo. Roman oil amphoras were frequently marked with information specifying their contents or manufacturer.

The trade industry in ancient Rome mobilised alongside her general staff of financiers and large-scale merchants a whole army of employees in her offices, of retailers in her shops, of artisans in her workshops, of the labourers necessary for the maintenance of her buildings and monuments, and of dockers to unload, store, and handle her colossal imports. Finally skilled workmen were needed to submit heavy raw materials as well as more delicate merchandise to a final transformation before they were handed on to the consumer. For Rome's distant subject peoples and those still more distant with whom they traded both within and without the imperial frontiers exhausted or enriched themselves to provide the city with what she demanded from every corner of the earth. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Some idea of the extent and variety of Roman trade can be gained by merely reading through the list of the corporations of Rome, drawn up by Waltzing at the beginning of the fourth volume of his masterly work. More than one hundred and fifty of them have been traced and accurately defined, and this is in itself enough to prove the mighty volume of business in which an aristocracy of patrons and a plebs of employees collaborated within one group, though it is impossible for us now always to distinguish the merchant from the financier, the trader from the master of industry, the manufacturer from the retailer. Among the wholesalers, the magnarii of corn, of wine, and of oil; among the shippers, the domini navium, who built, equipped, and maintained whole fleets, the engineers and repairers of boats (fabri navales et cur at ores navium), it is impossible to draw a hard and fast line between the middleman and the capitalist.

Importance of the Roman Grain and Olive Oil Trade

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: In a sense, Rome’s growth had always relied on its capacity to connect with ever-broadening Italian and Mediterranean trade networks. The more Rome expanded, the more it turned to outside resources to feed its population.By the beginning of the empire at the end of the first century B.C., the population of Rome and its environs had reached well over a million people. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2015]

Olive oil, wine, garum (a popular fish sauce), slaves, and building materials were shipped from places such as Spain, Gaul, North Africa, and the Near East. However, the most important responsibility of the Roman emperor was ensuring the steady and continuous flow of grain. Grains and cereals were the staple of the Roman diet, either consumed in bread form or served as a porridge. It has been estimated that a Roman adult consumed 400 to 600 pounds of wheat per year. With a population of more than a million, this required Rome to stock a staggering 650 million pounds annually. Throughout Rome’s history, shortages in the grain supply led to riots. The city’s food supply was frequently interrupted by storms and bad weather, and grain ships could be lost at sea. Any such delay or loss created civil unrest.

“From the second century B.C. onward, the Roman government took an increasingly active approach to monitoring and controlling the grain supply. First, the government began to regulate and subsidize the price, ensuring that grain remained affordable to the masses at all times. By the Augustan period, the emperor was doling out as much as 500 pounds of grain per head to as many as 250,000 households. The emperors realized that the key to Rome’s stability was keeping its population well fed.

“Yet, by the first century A.D., Rome could no longer be sustained by Italian harvests alone. It began to exploit its newly annexed fertile provinces, especially North Africa and Egypt, which soon became the largest supplier of Roman grain. It took as many as a thousand ships, constantly sailing, just to support the demand for grain in the city. With large grain ships typically capable of hauling more than 100 tons, and sea transport at least 40 times less expensive than land transport, Rome desperately needed a deepwater port close to home.

Olive was almost as important. In Rome, 50-meter (160-foot) -tall Monte Testaccio is an artificial hill made up almost entirely of olive oil amphoras from the ancient Roman province of Baetica in southern Spain.It takes about 20 minutes to walk around it and it’s circumference is almost a mile.Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: As the modern global economy depends on light sweet crude, so too the ancient Romans depended on oil — olive oil. And for more than 250 years, from at least the first century A.D., an enormous number of amphoras filled with olive oil came by ship from the Roman provinces into the city itself. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2015]

In the Roman Empire the Italian peninsula couldn’t produce nearly enough to meet the population’s needs. In addition to being one of the staples of the Mediterranean diet, olive oil was also used for bathing, lighting, medicine, and as a mechanical lubricant. During the emperor Augustus’s reign, olive oil as well as other products, including garum (the fish sauce Romans used to flavor everything from steamed mussels to pear soufflés), metals, and wine began to come into Rome as tax payment in kind from the provinces of Hispania (roughly modern Spain), especially Baetica. Over the next several hundred years, Baetican oil imports continued to grow, reaching their peak at the end of the second century A.D.

See Separate Articles: OLIVES, FRUITS AND VEGETABLES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ; BREAD IN ANCIENT ROME: GRAINS, MILLING AND PRISON-BAKERIES europe.factsanddetails.com

Greek Traders

The Greeks traded all over the Mediterranean with metal coinage (introduced by the Lydians in Asia Minor before 700 B.C.); colonies were founded around the Mediterranean and Black Sea shores (Cumae in Italy 760 B.C., Massalia in France 600 B.C.) Metropleis (mother cities) founded colonies abroad to provide food and resources for their rising populations. In this way Greek culture was spread to a fairly wide area. ↕

Greece was resource poor and overpopulated. They needed to colonize the Mediterranean to get resources. Beginning in the 8th century B.C., the Greeks set up colonies in Sicily and southern Italy that endured for 500 years, and, many historians argue, provided the spark that ignited Greek golden age. The most intensive colonization took place in Italy although outposts were set up as far west as France and Spain and as far east as the Black Sea, where the established cities as Socrates noted like "frogs around a pond." On the European mainland, Greek warriors encountered the Gauls who the Greeks said "knew how to die, barbarians though they were." [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, November 1994]

During this period in history the Mediterranean Sea was frontier as challenging to the Greeks as the Atlantic was to 15th century European explorers like Columbus. Why did the Greeks head west? "They were driven in part by curiosity. Real curiosity," a British historian told National Geographic. "They wanted to know what lay on the other side of the sea." They also expanded abroad to get rich and ease tensions at home where rival city-states fought with one another over land and resources. Some Greeks became quite wealthy trading things like Etruscan metals and Black Sea grain.

Trade Routes between Europe and Asia during Antiquity

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “New inventions, religious beliefs, artistic styles, languages, and social customs, as well as goods and raw materials, were transmitted by people moving from one place to another to conduct business. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Long-distance trade played a major role in the cultural, religious, and artistic exchanges that took place between the major centers of civilization in Europe and Asia during antiquity. Some of these trade routes had been in use for centuries, but by the beginning of the first century A.D., merchants, diplomats, and travelers could (in theory) cross the ancient world from Britain and Spain in the west to China and Japan in the east. The trade routes served principally to transfer raw materials, foodstuffs, and luxury goods from areas with surpluses to others where they were in short supply. Some areas had a monopoly on certain materials or goods. China, for example, supplied West Asia and the Mediterranean world with silk, while spices were obtained principally from South Asia. These goods were transported over vast distances— either by pack animals overland or by seagoing ships—along the Silk and Spice Routes, which were the main arteries of contact between the various ancient empires of the Old World. Another important trade route, known as the Incense Route, was controlled by the Arabs, who brought frankincense and myrrh by camel caravan from South Arabia. \^/

““Cities along these trade routes grew rich providing services to merchants and acting as international marketplaces. Some, like Palmyra and Petra on the fringes of the Syrian Desert, flourished mainly as centers of trade supplying merchant caravans and policing the trade routes. They also became cultural and artistic centers, where peoples of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds could meet and intermingle. \^/

““The trade routes were the communications highways of the ancient world. New inventions, religious beliefs, artistic styles, languages, and social customs, as well as goods and raw materials, were transmitted by people moving from one place to another to conduct business. These connections are reflected, for example, in the sculptural styles of Gandhara (modern-day Pakistan and northern India) and Gaul (modern-day France), both influenced by the Hellenistic styles popularized by the Romans. \^/

Trade between the Romans and the Empires of Asia

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “By the end of the first century B.C., there was a great expansion of international trade involving five contiguous powers: the Roman empire, the Parthian empire, the Kushan empire, the nomadic confederation of the Xiongnu, and the Han empire. Although travel was arduous and knowledge of geography imperfect, numerous contacts were forged as these empires expanded—spreading ideas, beliefs, and customs among heterogeneous peoples—and as valuable goods were moved over long distances through trade, exchange, gift giving, and the payment of tribute. Transport over land was accomplished using river craft and pack animals, notably the sturdy Bactrian camel. Travel by sea depended on the prevailing winds of the Indian Ocean, the monsoons, which blow from the southwest during the summer months and from the northeast in the fall. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org \^/]

Roman Gate in Petra

“A vast network of strategically located trading posts (emporia) enabled the exchange, distribution, and storage of goods. Isodorus of Charax, a Parthian Greek writing around the 1 A.D., described various posts and routes in a book entitled Parthian Stations. From the Greco-Roman metropolis of Antioch, routes crossed the Syrian Desert via Palmyra to Ctesiphon (the Parthian capital) and Seleucia on the Tigris River. From there the road led east across the Zagros Mountains to the cities of Ecbatana and Merv, where one branch turned north via Bukhara and Ferghana into Mongolia and the other led into Bactria. The port of Spasinu Charax on the Persian Gulf was a great center of seaborne trade. Goods unloaded there were sent along a network of routes throughout the Parthian empire—up the Tigris to Ctesiphon; up the Euphrates to Dura-Europos; and on through the caravan cities of the Arabian and Syrian Desert. Many of these overland routes ended at ports on the eastern Mediterranean, from which merchandise was distributed to cities throughout the Roman empire. \^/

“Other routes through the Arabian desert may have ended at the Nabataean city of Petra, where new caravans traveled on to Gaza and other ports on the Mediterranean, or north to Damascus or east to Parthia. A network of sea routes linked the incense ports of South Arabia and Somalia with ports in the Persian Gulf and India in the east, and also with ports on the Red Sea, from which merchandise was transported overland to the Nile and then to Alexandria.” \^/

Trade between Arabia and the Empires of Rome and Asia

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “South Arabian merchants utilized the Incense Route to transport not only frankincense and myrrh but also spices, gold, ivory, pearls, precious stones, and textiles—all of which arrived at the local ports from Africa, India, and the Far East. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "Trade between Arabia and the Empires of Rome and Asia", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Frankincense and myrrh, highly prized in antiquity as fragrances, could only be obtained from trees growing in southern Arabia, Ethiopia, and Somalia. Arab merchants brought these goods to Roman markets by means of camel caravans along the Incense Route. The Incense Route originally commenced at Shabwah in Hadhramaut, the easternmost kingdom of South Arabia, and ended at Gaza, a port north of the Sinai Peninsula on the Mediterranean Sea. Both the camel caravan routes across the deserts of Arabia and the ports along the coast of South Arabia were part of a vast trade network covering most of the world then known to Greco-Roman geographers as Arabia Felix. South Arabian merchants utilized the Incense Route to transport not only frankincense and myrrh but also spices, gold, ivory, pearls, precious stones, and textiles—all of which arrived at the local ports from Africa, India, and the Far East. The geographer Strabo compared the immense traffic along the desert routes to that of an army. The Incense Route ran along the western edge of Arabia’s central desert about 100 miles inland from the Red Sea coast; Pliny the Elder stated that the journey consisted of sixty-five stages divided by halts for the camels. Both the Nabataeans and the South Arabians grew tremendously wealthy through the transport of goods destined for lands beyond the Arabian Peninsula.” \^/

Travel by Water in the Roman Empire

Transport overland was slow and expensive. On sea it was cheap, but slow and risky in the winter. Roman used sailing vessels and river boats. There were, however, few transportation companies, few lines of boats or vehicles, that is, few running between certain places and prepared to carry passengers at a fixed price on a regular schedule. The traveler by sea whose means did not permit him to buy or charter a vessel for his exclusive use had often to wait at the port until he found a boat going in the desired direction and then make such terms as he could for his passage. And there were other inconveniences. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

J. A. S. Evans wrote: Bulky goods had to be carried by ship or riverboat, owned generally by a shipowner (navicularius) who sailed his own vessel, carrying cargoes of such goods as marble, timber, produce, firewood, or jars (amphorae) of wine or olive oil either on his own account or on consignment for others. Because the imperial government needed private shippers to carry supplies to Rome and to the army, the collegia of navicularii (leagues of shipowners) were the first trade alliances to be granted official recognition and privileges, for it was more efficient for the government to contract with them than with individual ship owners. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Collegia of navicularii are first known in great numbers in the time of Hadrian, and they remained free agents until the third century, when they were brought under the aegis of the imperial service. The largest vessels belonged to the Alexandrian grain fleet, which brought wheat from Egypt to Rome. Lucian of Samosata (The Ship i-ix) describes one ship of between 1,200 and 1,300 tons that was blown off course and reached the harbor of Piraeus after 70 days at sea. Grain shipments had to be suspended in winter. St. Paul's voyage to Italy on a grain transport (Acts 27.1–28) illustrates vividly the danger of trying to sail too late in the sailing season on the Mediterranean.

Because of the stormy weather in the Mediterranean during the winter ships usually stayed in port from October to March. Even during the Middle Ages, Venetian ships only made one trip a year between Italy and the Levant (present-day Lebanon). One fleet left Venice after Easter and returned in September.

RELATED ARTICLE: WATER TRANSPORTATION IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE: SEAGOING SHIPS, RIVER BOATS, PIRATES factsanddetails.com

Scale of Trade Revealed at Ancient Roman Port

In 1999, ABC Science reported: “ A detailed picture of the huge, vital and complex trade regimes in ancient Rome has been revealed by English and Italian archaeologists working on the remains of Portus, an ancient trading port. The investigation was led by Professor Simon Keay and Professor Martin Millett, University of Southampton in collaboration with Dr Helen Patterson, British School at Rome and Dr Anna Gallina Zevi and Dr Lidia Paroli, Soprintendenza Archeologica di Ostia. [Source:ABC Science, November 29, 1999 ]

“"Portus is the largest maritime infrastructure of the ancient world, created to guarantee the food supply of the population of Rome whose inhabitants numbered almost one million in the Imperial period," said the Soprintendente Archeologo di Ostia, Dr Anna Gallina Zevi. "Portus is therefore central to understanding one of the fundamental mechanisms of the economic life of Rome from its peak as an Imperial power to its decline in the early Middle Ages." "While the techniques of the geophysical survey are not new, the scale of this investigation, and its speed, have brought new possibilities to archaeological research. We've been able to map an area of 28 hectares in two weeks," said Professor Millett, "and new software allows us to analyse results and produce startling images of the buried structures."

“Portus was first built by the Emperor Claudius (AD 41-54), and was later enlarged by the Emperor Trajan (AD 98-117). It was a major port which handled all the trade and tribute destined for Rome, as well as the supplies for its provinces. Although the site has been known since the sixteenth century, excavation has been extremely limited, and little was previously known about the internal organization of Portus or about its links to the River Tiber and to Rome.

“Concentrating on the harbour of Trajan - a large hexagon linked to the sea and to the River Tiber - the archaeological team has discovered rows of warehouses and a colonnaded square along the eastern side of the hexagon. Even more significant are discoveries on flat land between the hexagon and the Tiber. Here the geophysics clearly reveal the line of the late Roman wall which defined the limits of the harbour area on its landward side. Also visible is a major canal, around 40m wide, which linked the Trajanic harbour to the river; this was lined with buildings in which pottery containers and marble from around the Mediterranean were unloaded. Running parallel to the canal are an aqueduct, the road to Rome, and a number of mausolea. The detailed images will allow precise excavations to be carried out in the future at particular buildings, which will further enhance knowledge of Portus and its historical development. A large part of the site will be open to public next year as part of Rome's millennium celebrations.”

RELATED ARTICLE: ANCIENT ROMAN INFRASTRUCTURE: BRIDGES, TUNNELS, PORTS factsanddetails.com

Land Travel in the Roman Empire

road in Leptis Magna Libya

Road travel was either on foot, or sedan chairs or litters for short distances or vehicles drawn by horses, oxen or mules for longer distance. In the springless carriages, carts or chariots it has been imagined that you that bounced and bumped over every cobblestone. Egyptians, Hittites, Aryans, Shang Dynasty Chinese and Assyrians had chariots long before the Greeks and Romans did

The Roman who traveled by land was distinctly better off than Americans of the time of the Revolution. His inns were not so good, it is true, but his vehicles and horses were fully equal to theirs, and his roads were the best that have been built until very recent times. Horseback riding was not a recognized mode of traveling (the Romans had no saddles), but there were vehicles, covered and uncovered, with two wheels and with four, for one horse and for two or more. These were kept for hire outside the gates of all important towns, but the price is not known. To save the trouble of loading and unloading the baggage it is probable that persons going great distances took their own vehicles and merely hired fresh horses from time to time. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“There were, however, no post-routes and no places where horses were changed at the end of regular stages for ordinary travelers, though there were such arrangements for couriers and officers of the government, especially in the provinces. For short journeys and when haste was not necessary, travelers would naturally use their own horses as well as their own carriages. Of the pomp which often accompanied such journeys. |+|

RELATED ARTICLE: LAND TRANSPORTATION IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE: VEHICLES, TRAFFIC, INNS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

Warehouses in the Roman Empire

In Rome and its suburbs the sheds of the warehouses (horrea) stretched out of sight. Here accumulated the provisions that filled Rome's belly, the stores that were the pledge of her well-being and of her luxury. The excavations undertaken in 1923 by the late Prince Giovanni Torlonia have revealed the importance of the horrea of the Portus of Trajan; though only one-third of the area covered in Hadrian's day by the horrea of Ostia has so far been excavated, they already cover some ten hectares. The discovery of the ancient Roman horrea, the number and extent of which are indicated in the literature of the time, began in the ear;y 20th century. Some of these specialised in a single type of goods: the horrea candelaria stored only torches, candles, and tallow; the horrea chart aria on the Esquiline were consecrated to rolls of papyrus and quires of parchment; while the horrea piperataria near the Forum were piled with the supplies of pepper, ginger, and spices convoyed there by the Arabs.

Most of the horrea, however, were a sort of general store where all kinds of wares lay cheek by jowl. They were differentiated by the name of the place they occupied or the name they had inherited from their first proprietor and retained even when they had passed into the hands of the Caesars the horrea Nervae flanked the Via Latina; the horrea Ummidiana lay on the Aventine; the horrea Agrippiniana between the Clivus Victoriae and the Vicus Tuscus on the fringe of the Forum; others were grouped between the Aventine and the Tiber.

Then there were the horrea Seiana, the horrea Lolliana, and the most important of all the horrea Galbae, whose foundation went back to the end of the second century B.C. The horrea Galbae were enlarged under the empire and possessed rows of tabernae ranged round three large intermediate courtyards which covered more than three hectares. In these tabernae were stocked not only wirie and oil but all sorts of materials and provisions, at least if we are to judge by the inscriptions deciphered by the epigraphists indicating the merchants to whom these "granaries" gave shelter: in one place a woman fish merchant (piscatrix), in another a merchant of marbles (marmorarius), farther off an outfitter with tunics and mantles for sale (sagarius).

Trade and Business at Vindolanda

On a letter that touches on trade from Vindolanda near Hadrian's Wall in northern England, Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “A long and very well preserved letter, from Octavius to his brother Candidus, gives us the names of these two brothers and portrays them as a couple of local wide-boys, with their fingers in as many pies as possible (Tab. Vindol. II 343): “Octavius to his brother Candidus, greetings. The hundred pounds of sinew from Marinus, I will settle up. From the time when you wrote about this matter, he has not even mentioned it to me. I have several times written to you that I have bought about 5,000 modii of ears of grain, on account of which I need cash. Unless you send me some cash, at least 500 denarii, the result will be that I shall lose what I have laid out as a deposit, about 300 denarii, and I shall be embarrassed. So, I ask you, send me some cash as soon as possible. The hides which you write are at Cataractonium, write that they be given to me and the wagon about which you write. And write to me what is with that wagon. I would have already have been to collect them except that I did not care to injure the animals while the roads are bad. See with Tertius about the 8½ denarii which he received from Fatalis. He has not credited them to my account. Know that I have completed the 170 hides and I have 119(?) modii of threshed bracis. Make sure that you send me some cash so that I may have ears of grain on the threshing room floor. Moreover, I have already finished threshing all that I had. A messmate of our friend Frontius has been here. He was wanting me to allocate(?) him some hides, and that being so, was ready to give cash. I told him I would give him the hides by the Kalends of March. He decided that he would come on the Ides of January. He did not turn up, nor did he take the trouble to obtain them since he had hides. If he had given the cash, I would have given him them. I hear that Frontinius Julius has for sale at a high price the leather ware(?) which he bought here for five denarii apiece. Greet Spectatus and ...and Firmus. I have received letters from Gleuco. Farewell. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, November 16, 2012 |::|]|

“Candidus was obviously so well known in the fort that his brother did not need to put his name on the back for whoever was delivering the note. The two seem to have the supply of grain to Vindolanda sewn up (which is interesting when you consider that the military granary of Corbridge was just down the road). The regular allocations to Macrinus and Crescens are probably rations doled out to individual unit centurions: since a Crescens is named as a centurion of III Batavorum. In that case, who are Firmus and Spectatus? Clearly Firmus is a key individual, as he has the authority to allocate grain to a detachment of legionaries in the fort; yet does this mean that he is a senior centurion of one of the cohorts, or is he just a middle-man? Since Spectatus uses grain as a loan to Victor, it seems most likely that they were agents of the brothers (though this does not necessarily stop them being soldiers). |::|

“I think it is clear that the two brothers were civilian entrepreneurs, and when you consider that the annual pay of an auxiliary soldier at this time was about 300 denarii, they were obviously not in the little-league if they could fork out 500 denarii for their grain supplies. The fact that they had Roman names can tell us little, since anyone who wanted to get on is likely to have 'Romanised' by this time. One possibility does come to mind. Given the Roman penchant for farming out public services (like tax-collecting and mining) to individual entrepreneurs, it is possible that these two men had the contract for supplying grain to the army from Corbridge.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024