LABOR AND CLASS IN THE ROMAN ERA

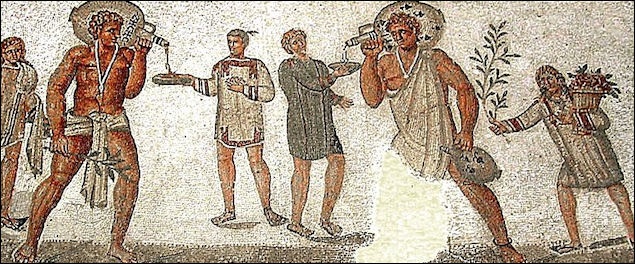

Household slave and her master

People did not always work for a wage in the ancient world. Most people worked on the land and in the home, while upper-class men and women supervised households and estates. It is evident from what has been said that abundant means were necessary to support the state in which every Roman of position lived. It will be of interest also to see how the great mass of the people made the scantier living with which they were forced to be content. For the sake of the inquiry it will be convenient, if not very accurate, to divide the people of Rome into the three great classes of nobles, knights, and commons into which political history has distributed them. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

The “nobles” during the Republic had come to be the descendants of those men who had held curule office. As the senate was composed of those men who had held the higher magistracies, the nobles and the senatorial families were practically the same, for the political influence of this group was so strong that it was very difficult for a “new man” (novus homo) to be elected to office. At the same time it must be remembered that for a long time there was no hard and fast line drawn between the classes; a noble might, if he pleased, associate himself with the knights, provided the noble possessed $20,000 which one must have to be a knight. |+|

During the Republic any free-born citizen might aspire to the highest offices of the State, however poor in pocket or talent he might be. The drawing of definite lines that under the later Empire fixed citizens in hereditary castes began under Augustus, when he limited eligibility for the curule offices to those whose ancestors had held such offices. This regulation formed a hereditary nobility, to which additions were made at the emperor’s pleasure. The emperor also revised the lists of the knights, and so controlled admission to that Order.|+|

RELATED ARTICLES:

TRADESMEN AND PROFESSIONS IN THE ROMAN ERA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SLAVES IN ANCIENT ROME: NUMBERS, LAWS, FREEDOM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SLAVE TRADE IN ANCIENT ROME: SOURCES, SALES AND ECONOMIC IMPACT europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TYPES OF SLAVES AND SLAVE-LIKE PEOPLE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Working Lives in Ancient Rome” by Del A. Maticic and Jordan Rogers (2024) Amazon.com;

“Work and Labour in the Cities of Roman Italy”by Miriam J. Groen-Vallinga (2024)

Amazon.com;

“Land and Labour: Studies in Roman Social and Economic History” by Jesper Carlsen (2013) Amazon.com;

“Valuing Labour in Greco-Roman Antiquity” by Miko Flohr and Kim Bowes (2024) Amazon.com;

“Work, Labour, and Professions in the Roman World” (English and Latin Edition)

by Koenraad Verboven and Christian Laes (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Dignity of Labour: Image, Work and Identity in the Roman World”

by Iain Ferris (2021) Amazon.com;

“Skilled Labour and Professionalism in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Edmund Stewart , Edward Harris, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Strike: Labor, Unions, and Resistance in the Roman Empire” by Sarah E Bond (2025) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in the Roman World” by Sandra R. Joshel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275–425" by Kyle Harper (2016) Amazon.com;

“Roman Artisans and the Urban Economy” by Cameron Hawkins (2021) Amazon.com;

“Urban Craftsmen and Traders in the Roman World” by Andrew Wilson and Miko Flohr (2016) Amazon.com;

“Carving as Craft: Palatine East and the Greco-Roman Bone and Ivory Carving Tradition”

by Archer St. Clair Amazon.com;

“Roman Woodworking” by Roger B. Ulrich (2013) Amazon.com;

“How the Greeks and Romans Made Cloth” (Cambridge School Classics Project)

Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present” by Eric Broudy (2021) Amazon.com;

“Garum and Salsamenta: Production and Commerce in Materia Medica” by Robert I. Curtis (1991) Amazon.com;

“Roman and Late Antique Wine Production in the Eastern Mediterranean: A Comparative Archaeological Study at Antiochia ad Cragum (Turkey) and Delos (Greece)” by Emlyn Dodd | (2020) Amazon.com;

“Wine in Ancient Greece and Cyprus: Production, Trade and Social Significance”

by Evi Margaritis, Jane M. Renfrew, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“From Vines to Wines in Classical Rome” by David L. Thurmond (2016) Amazon.com;

“Roman Building” by Jean-Pierre Adam (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Different Modes Of Construction Employed In Ancient Roman Buildings And The Periods When Each Was First Introduced” by John Henry Parker (1868) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Workers in Ancient Rome

With the possible exception of the principal dock quarter on the banks of the Tiber and the slopes of the Aventine, the Roman workers did not live congregated in dense, compact, exclusive masses. Their living quarters were scattered about in almost every corner of the city, but nowhere did they form a town within the town. Instead of being concentrated in an immense bazaar or a monster factory area, their dwellings formed indefinite series with a hundred interruptions, so that in the Urbs warehouses, workshops, and workmen's dwellings alternated oddly with private mansions and blocks of flats. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The system of their corporations, co-ordinated by Augustus' legislation and the edicts of his successors, permitted each trade body to set up rules valid for all its members. Apart from certain people like the tavern-keepers or the "antiquaries" who wished to tempt the strollers in the Saepta lulia until the last moment, and who therefore did not shut down till the eleventh hour, or the tonsores who had to fit their work into their customers leisure and who kept open till the eighth hour, by far the greater number of Roman workers downed tools either at the sixth or the seventh hour; no doubt the sixth in summer and the seventh in winter. If one bears in mind that the "hour" at the winter solstice equalled forty-five minutes according to our reckoning and seventy-five minutes at the summer solstice, these data bring the Roman working day down to about seven hours in summer and less than six in winter.

Summer and winter alike, Roman workmen enjoyed freedom during the whole or the greater part of the afternoon, and very probably our forty-hour week with its different arrangement would have weighed heavily on them rather than pleased them. Their rural habits, in the first place, and in the second their sense of their incomparable superiority, guarded them against unremitting labour and harassing tasks. So much so that at the time when Martial was writing, the merchants and shopkeepers, the artisans and labourers of the imperial race, upheld by their vital professional unions, had succeeded in so organising their work as to allow themselves seventeen or eighteen of our twentyfour hours for the luxury of repose and enjoyed what we may call if we care to the leisure of people of means.

Jobs in Ancient Rome

"superiority of the warrior class"

Among the members of the Roman workforce were shield makers, bath attendants, blacksmiths and medical orderlies. Romans had many skilled individuals including drillmaster for training, fortress engineers and aqueduct designers. Slaves did nearly all the work, the worked the fields and the mines, they practiced medicine and tutored children. They ran stores and delivered mail.

The Employments of the Romans comprised many of the chief occupations and trades with which we are familiar to-day, including professional, commercial, mechanical, and agricultural pursuits. To the learned professions belonged the priest, the lawyer, the physician, and the teacher. The commercial classes included the merchant, the banker, the broker, the contractor, to whom may also be added the taxgatherer of earlier times. The mechanical trades comprised a great variety of occupations, such as the making of glass, earthenware, bread, cloth, wearing apparel, articles of wood, leather, iron, bronze, silver, and gold. The artisans were often organized into societies or guilds (collegia) for their mutual benefit; these guilds were very ancient, their origin being ascribed to Numa. The agriculturists of Rome comprised the large landowners, who were regarded as a highly respectable class, and the small proprietors, the free laborers, and the slaves, the last mentioned forming a great part of the tillers of the soil. In general, the Roman who claimed to be respectable disdained all manual labor, and resigned such labor into the hands of slaves and freedmen. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The professions and trades, between which the Romans made no distinction, in the last years of the Republic were practically given over to the libertini and to foreigners. Of these something has been said already. Some occupations were considered unsuitable for a gentleman. Undertakers and auctioneers were disqualified for office by Caesar. Architecture was considered respectable. Cicero put it on a level with medicine.1 Teachers were poorly paid and were usually looked upon with contempt. Vespasian first endowed professorships in the liberal arts. The place of the modern newspaper was taken by letters written as a business by persons who collected all the news, scandal, and gossip of the city, had it copied by slaves, and sent it to persons away from the city who did not wish to trouble their friends and who were willing to pay for the news. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Manual services (operae) included tanners (corarii), the furriers (pelliones), the ropemakers (restiones), the caulkers (stuppatores), the carpenters and cabinet-makers (citrarii), the metal workers in bronze and iron (fabri aerarii, f errant). In the second category we may include the building corporations: the wreckers (subrutor es), the masons (structores), the timber workers (fabri tignarii) ; the workers responsible for land transport: muleteers (muliones), those in charge of pack animals (iumentarii), waggoners (catabolenses), carters (vectuarii), drovers (cisiarii); those responsible for water transport: boatmen (lenuncularii), oarsmen (lintrarii), coasters (scapharii), raftsmen (caudicarii), towers (helicarii), ballast-loaders (saburrarii) ; and filially, the corporations on whom depended the administration and policing of the docks: the guardians (custodiarii), the porters (baiuli), the stevedores (geruli), the wharfmen (saccarii). [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

A fresco in the House of the Vettii in Pompeii depicts a carpenter using a hammer and chisel to carve notches in a piece of wood. Other woodworking tools lie on the ground. Dr Joanne Berry wrote for the BBC: “This wall-painting is rare evidence of a craft that must have had an important role to play in the ancient city (particularly so in Pompeii, after the devastating earthquake that shook the town in A.D. 62), yet which normally leaves little trace in the archaeological record. In general, we know much more about crafts that needed large-scale equipment - such as milling, baking, fulling (cleaning cloth), dying, and tanning. Around 200 workshops of different kinds so far have been identified in Pompeii.” [Source: Dr Joanne Berry, Pompeii Images, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

Soldiers Versus Workers in Ancient Rome

The free-born citizens of Rome below the nobles and the knights may be roughly divided into two classes, the soldiers and the proletariat. The civil wars had driven them from their farms or had unfitted them for the work of farming, and the pride of race or the competition of slave labor had closed against them the other avenues of industry, numerous as these must have been in the world’s capital. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The best of these free-born citizens turned to the army, which had ceased to be composed of citizen-soldiers, called out to meet a special emergency for a single campaign, and disbanded at its close. From the time of the reorganization by Marius, at the beginning of the first century before our era, this was what we should call a regular army, the soldiers enlisting for a term of twenty years, receiving stated pay and certain privileges after an honorable discharge. In time of peace—when there was peace—they were employed on public works.

“The pay was small, perhaps forty or fifty dollars a year with rations in Caesar’s time, but this was as much as a laborer could earn by the hardest kind of toil, and the soldier had the glory of war to set over against the stigma of work, and hopes of presents from his commander and the privilege of occasional pillage and plunder. After he had completed his time, he might, if he chose, return to Rome, but many had formed connections in the communities where their posts were fixed and preferred to make their homes there on free grants of land, an important instrument in spreading Roman civilization.” |+|

Workers, Free Laborers and the Unemployed in Ancient Rome

tomb of fishmonger and freedwoman

The Proletariat. In addition to the idle and the profligate attracted to Rome by the free grain and by the other allurements that bring a like element into our cities now, large numbers of the industrious and the frugal had been forced into the city by the loss of their property during the civil wars and the failure to find employment elsewhere. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

No exact estimate of the number of these unemployed people can be given, but it is known that before Caesar’s time it had passed the mark of 300,000. Relief was occasionally given by the establishing of colonies on the frontiers—in this manner Caesar put as many as 80,000 in the way of earning their living again, short as was his administration of affairs at Rome—but it was the least harmful element that was willing to emigrate. The dregs were left behind. Aside from beggary and petty crimes the only source of income for such persons was the sale of their votes; this made them a real menace to the Republic. Under the Empire their political influence was lost, and the State found it necessary to make distributions of money occasionally to relieve their want. Some of them played client to the upstart rich, but most of them were content to be fed by the State and amused by the shows and games.

“Literature has little to say about the free laborer. Inscriptions, particularly those that deal with the guilds, tell us more. In spite of the increase of slave labor and the decrease of the native Italian stock, there continued to be free laborers working in many lines, their numbers constantly swelled by the manumission of slaves. They worked at many trades, at heavy labor, in the cities, and even on the farms. They were not always as well off as many of the slaves or freedmen, as they were dependent on their own efforts and the labor market and were without owner or patron on whom they might fall back. It is difficult to learn anything about wages, but they cannot have been high. The free distribution of grain helped the poor citizen at Rome, and vegetables, fruits, and cheese made the rest of his diet. He could nearly always afford a little cheap wine to mix with water. If he married, his wife helped by spinning or weaving. He lived in a cheap tenement, and in that mild climate there was no fuel problem. His dress was a rough tunic; if shoes were worn they were wooden shoes or cheap sandals. The public games gave him amusement on the holidays, and the baths were cheap, when not free. The guild gave him his social life, and decent burial was provided by membership in guild or burial society. |+|

Work Done at the Roman Forum

At the eastern end of the Roman Forum the caulkers and the ropemakers had their statio; in the next room the furriers; next came the wood merchants, whose name is enclosed in a dovetail cartouche; then the corn measurers (the mensores frumentarii), one of whom is shown performing his duties, one knee on the ground, diligently trying to divide the contents of a modius or regulation bushel exactly with his scraping tool or rutellum. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

At the opposite end was the statio of the weighers or sacomarii, whose business was complementary to that of the mensores. In 124 B.C. the weighers here dedicated to the genius of their office a charming carved altar which is now exhibited in the Museo Nazionale delle Terme. This leaves little doubt that this statio and the other similar ones were formerly dedicated to some cult.

All the others belonged to the corporations of fitters (weighers, navicularii), who were further distinguished among themselves only by their city of origin. There were the fitters of Alexandria, for instance, the fitters of Narbonne and Aries in Gaul, those of Cagliari and Porto-Torres in Sardinia. There were those, of celebrated or forgotten ports in northern Africa; Carthage, whose mercantile fleet the mosaic artist has stylised; Hippo-Diarrhytus, the modern Bizerta; Curbis, now Courba to the north of the Gulf of Hammamet; Missua, now Sidi Daud, south-west of Cape Bon; Gummi, now Bordj Cedria, at the base of the Gulf of Carthage. There were the fitters of Musluvium, now Sidi Rekane, between Ziama and Bougie, whose somewhat complicated and yet highly instructive armorial bearings include fish, a cupid astride a dolphin, and two female heads, one of which is almost effaced while the other is crowned with ears of corn and has a harvest woman's sickle at its side. And finally there were the fitters of Sabratha, the port of the desert whence the ivory of Fezzan was exported, symbolised by an elephant below the name of its seamen.

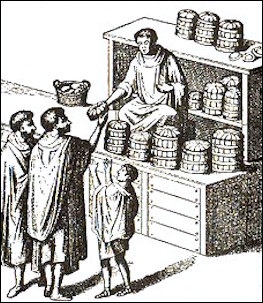

Bakeries and Bread-Sellers in Ancient Rome

Dr Joanne Berry wrote for the BBC: A wall-painting from Pompeii “depicts the sale of bread - loaves of bread are stacked on the shop counter, and the vendor can be seen handing them to customers. It is thought that the inhabitants of Pompeii bought their daily bread from bakeries rather than baked it themselves at home, since ovens rarely are found in the houses of the town.” The high “number of bakeries that have so far been excavated tends to support this belief. Bakeries are identified by the presence of stone mills to grind grain, and large wood-burning ovens for baking. [Source: Dr Joanne Berry, Pompeii Images, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

“Bread may have been bought directly from the bakery, but it is likely that it was also sold from temporary stalls set up at different parts of the town. Two graffiti discovered on the precinct wall of the Temple of Apollo are an indication of this. They read Verecunnus libarius hic and Pudens libarius, which can be roughly translated as 'Verecunnus and Pudens sell sacrificial bread here'. |::|

bread selling

Lava mills and the large wood-burning oven identify” a building “as a bakery. Each mill consists of two mill-stones, one stationary and one hollow and shaped like a funnel. The funnel-shaped stone had slots, into which wooden levers could be inserted so that the stone could be rotated. Each mill would have been operated either by manpower or with the help of a donkey or horse (in one bakery, the skeletons of several donkeys were discovered). In order to make flour, grain was poured from above into the hollow stone and then was ground between the two stones. In total, 33 bakeries have so far been found in Pompeii. The carbonised remains of loaves of bread were found in one, demonstrating that the oven was in use at the time of the eruption in A.D. 79.” |::|

Charles King wrote in his website “A History of Bread”: “A Bakers’ Guild was formed in Rome round about the year 168 B.C. From then on the industry began as a separate profession. The Guild or College, called Collegium Pistorim. did not allow the bakers or their children to withdraw from it and take up other trades. The bakers in Rome at this period enjoyed special privileges: they were the only craftsmen who were freemen of the city, all other trades being conducted by slaves. [Source: Charles King, “A History of Bread” botham.co.uk/bread |~|]

“The members of the Guild were forbidden to mix with ‘comedians and gladiators’ and from attending performances at the amphitheatre, so that they might not be contaminated by the vices of the ordinary people. We suppose that the bakers, instead of being honoured by the strict regulations, must have felt deprived by them. |~|

Milling Grain for Bread — One of the Worst Jobs in Ancient Rome

The Romans had no public mills distinct from bakeries; each baker was also a miller. Candida Moss wrote in Daily Beast: Working a mill was one of the most feared and laborious tasks in the ancient world. It was a punishment for rebellious enslaved workers and a mere step up from the death-sentence of working in the mines. Archeological evidence shows that mill workers and miners may have even worked together to select materials and ease their burden. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, October 3, 2021]

“Small hand-mills — which were used by domestic bakers in antiquity as well — aren’t too cumbersome and they are a step up from a mortar and pestle. But the larger hourglass and rotary mills used in Roman bakeries involved physical strength and were often powered by donkeys and “chained convicts” (as Pliny noted in his Naturalis Historia). The hourglass mills, which can still be seen in the bakeries at Pompeii, were comprised of a solid bell-shaped stone over which a hollow hourglass shaped stone was placed. The hourglass stone both functioned like a hopper that fed grain into the mill and was also turned around the base stone to grind the grain. The worker (human or donkey) would circle the mill turning the hourglass stone as he walked.

“Working in a mill was so tough that it was a form of punishment. Messenio, a character in the playwright Plautus’ Menaechmi, lists being sent to the mill alongside being whipped or placed in fetters as a punishment for laziness. In the mill, Messenio says, the disobedient enslaved worker would find himself hungry, exhausted, and cold. As Professor Sarah Bond writes in her book Trade and Taboo, “laboring in the mill was better than being sent to the mines, [but] it was still a terrible punishment. ” Mill prisons, she writes, remained a reality in the Roman empire though, and from the fourth century A. D., they were sometimes staffed by a mix of enslaved and penal workers. With much of the Roman empire being sustained by a grain-based diet, there was always a demand for workers.

“Even enslaved children learned to fear the mill. A beautiful piece of graffiti etched into the wall of a school for enslaved children in second-century Rome shows a donkey turning a mill. The child who wrote the inscription — in lettering worthy of a high-quality manuscript — expresses the hope that having worked hard in school, he will, as an educated scribe or copyist, be able to escape the threat of the mill.

Jobs Regarded with Contempt in Antiquity

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In her extraordinary book Trade and Taboo, University of Iowa professor Sarah Bond describes the way that participation in certain trades marginalized people from ancient society. The denigration of some of these careers might make sense to us (sex work is stigmatized to this day), but as it turns out many people performed important jobs in the ancient world and yet found themselves pushed to the fringes of society because of it.

Arguably the most easy to understand stigmatized profession was that of the funerary worker. The funerary trade was a vital part of the ancient economy, but the Romans believed that corpses were full of pollution; pollution that emanated from the bodies themselves meant that funeral workers were excluded from life in the ancient city. They worked at night and could not participate in religious rituals or perform sacrifices. A.D. inscription from Puteoli in Southern Italy describes how there were restrictions on where those who buried the dead could live, when they were permitted to bathe, and the circumstances upon which they could enter the city. If they did enter the city walls they were required to wear distinctive caps in order to mark them as members of the ostracized group.

shop activity

The obsession with death pollution can help explain why it was that praecones, crier-auctioneers (an auctioneer/town-crier hybrid), were also socially marginalized. Criers were a critical means of disseminating information in the largely illiterate ancient world, but the practice of selling one’s voice was stigmatized because of the frequency with which criers were tasked with announcing deaths and funerals. It seemed to people in the ancient world that criers were profiteering from events, and that led to them being viewed as a threat. The most tangible result of this was that criers were prevented from holding municipal office.

While some professions were viewed with contempt because of attitudes towards dead bodies and financial profiteering, others were legally immobilized by the emperor precisely because of their importance to the state. Bond shows how Roman authorities restricted the social liberties of mint workers because their role in facilitating the dissemination of money was essential to the state. There were some perks to these jobs: in the later Roman empire mint workers were exempt from military service and, by the sixth century, actually became high status. But in the early empire controlling low-level workers was about controlling the empire.

It wasn’t only the Romans who stigmatized certain professions. Early Christians inherited their prejudices and viewed participation in certain trades as precluding a person from joining the movement. The Apostolic Tradition, a third-century text attributed to St. Hippolytus of Rome, has its own list of unacceptable careers for prospective candidates for baptism. These include prostitute, brothel keeper, garment trimmers, gladiators, charioteers, artists, actors, soldiers, teachers, and politicians. The rationale for excluding these professions was largely that they were associated with idolatry, sexual immorality and violence, but they demonstrate our shifting sense of those career paths that are socially and religiously acceptable.

But this isn’t even about perceptions of sexual immorality; professional stigmatization in ancient Rome had legal and, thus, social repercussions. It was not only prostitutes who were shut out of the marriage market; the social taboos that surrounded working with the dead pushed funerary workers to the margins of the society. The disjuncture between economic interconnectivity and social affluence meant that people who performed vital tasks for the empire could be shuffled out of sight. They became socially and politically vulnerable, even though they were critically important to the social world that they served. Bond argues that shadows of Roman prejudice are long and that the social disrepute calcified by Roman law took centuries to dislodge.

Foul-Smelling Jobs in Ancient Rome

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The sensitivities that surrounded smell meant that ancient tanners (leather workers) were ostracized. In order to soften the hides, tanners used noxious-smelling astringents (including urine). As a result, tanneries in Rome were often located outside of the city, in locations where the smell was less bothersome to the people of the city. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 13, 2016]

So far, this makes intuitive sense: very few of us want to live next to foul-smelling industrial plants. What’s interesting about it, though, is that while many things in the ancient world smelled atrocious, tanneries were especially singled out by ancient authors. Moreover, as geographically removed as the archeological evidence suggests tanners were, the literary evidence exaggerates the distance even further. What we can conclude from this is that the social stigmatization outstripped the physical reality. Tanners may have been physically pushed out of city centers, but they were socially forced into further exile.

Then there were the purveyors of luxury foodstuffs. The famed Roman orator Cicero wrote that professions that catered to voluptas (sensual pleasure) were the least respectable of all. Fishermen, cooks, bakers, and butchers were seen not only as debased but also as effeminate. The prejudice was so strongly ingrained in Roman society that they were excluded from the late antique Roman military. Over time, and because of their centrality to the continued success of the military (everyone needs bread, after all), bakers would rise up the social hierarchy. But for many the character and manliness of those engaged in the luxury food trades was eyed with suspicion.

Working Women in Ancient Rome

Suzanne Dixon wrote for the BBC: Although there were specialist cloth shops, all women were expected to be involved in cloth production: spinning, weaving and sewing. Slave and free women who worked for a living were concentrated in domestic and service positions - as perhaps midwives, child-nurses, barmaids, seamstresses, or saleswomen. We do, however, have a few examples of women in higher-status positions such as that of a doctor, and one woman painter is known. [Source: Suzanne Dixon, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

“How do we know about women's work? From men saying in print what women should be doing - poets (like Virgil), and philosophers (like Seneca), and husbands praising their dead wives on tombstones not only for being chaste (casta) but also for excelling at working wool (lanifica). |We can also learn about women's work from pictures on vases and walls (paintings), or from sculptural reliefs on funerary and public art. Septimia Stratonice was a successful shoemaker (sutrix) in the harbour town of Ostia. Her friend Macilius decorated her burial-place with a marble sculpture of her, on account of her 'favours' to him (CIL 14 supplement, 4698). Graffiti such as the ones on the wall of a Pompeian workshop record the names of women workers and their wool allocations - names such as Amaryllis, Baptis, Damalis, Doris, Lalage and Maria - while other graffiti are from women workers' own monuments, usually those of nurses and midwives (see CIL 14.1507). Women's domestic work was seen as a symbol of feminine virtue, while other jobs - those of barmaid, actress or prostitute - were disreputable. Outside work like sewing and laundering was respectable, but only had a low-status. Nurses were sometimes quite highly valued by their employers/owners, and might be commemorated on family tombs.” |::|

Among the thousands of epitaphs of the Urbs collected by the editors of the Cor pis Inscriptionuin Latin irum a few refer to women earners: one libraria or woman secretary, three clerks (amanuenses), one stenographer (notaria) two women teachers against eighteen of the other sex, four women doctors against fifty-one medici. For the great bulk of Roman women the civil registers would have required the entry less and less familiar in ours "no profession." In the urban epigraphy of the empire we find women fulfilling the duties such as seamstress (sarcinatrix), woman's hairdresser (tonstrix, ornatrix) midwife (obstera:), and nurse (nutrix).[Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

As of the 1930s, only one fishwife (piscatrix) one female costermonger (negotiatrix leguminaria) one dressmaker (vestifica) has been discovered against twenty men tailors or vestifici three woman wool distributors (lanipendiae), and two silk merchants (sericariae). We need feel no surprise at the absence of women jewellers; for one thing, at Rome there was no clear demarcation between the argentarii who sold jewellery and the argentarii who took charge of banking and exchange; and for another, all banking operations had been forbidden to women by the same praetorian legislation that had deprived them of the right to sue on each other's behalf.

It is surely noteworthy that women never figure in the corporations for which the emperors tried to stimulate recruitment: naval armament in the time of Claudius and baking under Trajan. There are not any woman's name in the lists of shippers which have survived to our times. Women are equally absent from most of the paintings of Herculaneum and Pompeii, and from the funerary bas-reliefs where the sculptor has pictured scenes in the streets and represented to the life the animation of buyers and sellers. We find woman depicted only in scenes where her presence was more or less obligatory and inevitable: where the fuller brought back the clean clothes to the lady of the house; when a widow came to the marble merchant (marmorarius) to order a tomb for her dead husband; when the bootmaker tried on shoes one by one.

Jobs for the Boys in Roman Britain

Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “Another report of work assignments shows how these men could be employed. Of 343 men present, 12 were making shoes, 18 were building the bath-house, others were out collecting lead, clay and rubble (for the bath-house?), while still more were assigned to the wagons, the kilns, the hospital and on plastering duty. Other accounts indicate that the completed bath-house had a balniator, a bath-house keeper called Vitalis. The remains of the third-century bath-house on the site give a very good idea of what Vitalis' bath-house must have been like. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, November 16, 2012 |::|]

“Other trades attached to the fort were two vets called Virilis and Alio, a shield-maker called Lucius, a medic called Marcus and a brewer called Atrectus. Most of these must have been soldiers, though we shall see later that civilians also played their part within fort life. Atrectus the brewer owed money to the local pork butcher for iron and pork-fat, which smacks of a little economic diversification on the butcher's part. It is not at all clear whether the butcher was a civilian or a soldier. He is likely to have been a civilian, if two other documents are anything to go by. The first is an intriguing account of wheat which, to me, paints a marvellous picture of everyday life at the fort. It is a long account, so I have excerpted only the clearest entries. [NB: a modius is a measure of weight] (Tab. Vindol. II.180): |::|

“Account of wheat measured out from that which I myself put into the barrel: To myself, for bread... To Macrinus, modii 7 To Felicius Victor on the order of Spectatus, provided as a loan, modii 26 In three sacks, to father, modii 19 To Macrinus, modii 13 To the oxherds at the wood, modii 8 Likewise, to Amabilis at the shrine, modii 3 To Crescens, on the order of Firmus, modii 3 For twisted loaves, to you, modii 2 To Crescens, modii 9 To the legionary soldiers, on the order of Firmus, modii 11[+] To you, in a sack from Briga... To Lucco, in charge of the pigs... To Primus, slave of Lucius... To Lucco for his own use... In the century of Voturius... To father, in charge of the oxen... Likewise to myself, for bread, modii ? Total of wheat, modii 320½” The document is clearly the account of a family business run by two brothers, whose father occasionally tends the oxen. |::|

Clients and Hospites — Slave-Like Dependents — in Ancient Rome

The word clients is used in Roman history of two very different classes of dependents, who are separated by a considerable interval of time and may be roughly distinguished as Old Clients and New Clients. The former played an important part under the Kings, and especially in the struggles between the patricians and plebeians in the early days of the Republic, but had practically disappeared by the time of Cicero. The latter are first heard of after the Empire was well advanced, and never had any political significance. Between the two classes there is absolutely no connection, and the student must be careful to notice that the later class is not a development of the earlier. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Hospites in strictness ought not to be reckoned among the dependents. It is true that they were often dependent on others for protection and help, but it is also true that they were equally ready and able to extend like help and protection to others who had the right to claim assistance from them. It is important to observe that hospitium differed from clientship in this respect, that the parties to it were actually on the footing of absolute equality. Although at some particular time one might be dependent upon the other for food or shelter, at another time the relations might be reversed and the protector and the protected change places.

See Separate Article: TYPES OF SLAVES AND SLAVE-LIKE PEOPLE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and Roman Forums

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024