SEASONALITY OF WAR IN THE ROMAN ERA

“During the Romans’ early history, the logistical challenges of conducting a war meant that the Romans only fought between sowing and harvest (during the summer). Rome was an agriculture-based economy, and the movement of troops during winter was highly demanding. The first recorded continuation of war into the winter by the Romans took place in 396 B.C. during the siege of the Etruscan city of Veii. [Source: Cristian Violatti, Listverse, September 4, 2016 ]

“According to Livy (History of Rome, 5.6), if a war was not over by the end of summer, “our soldiers must wait through the winter.” He also mentioned a curious way that many soldiers chose to spend the time during the long waiting: “The pleasure of hunting carries men off through snow and frost to the mountains and the woods.”.

In case of war in the Republican Era, it was customary to raise four legions, two for each consul. Each legion was composed of thirty maniples, or companies, of heavy-armed troops,—twenty maniples consisting of one hundred and twenty men each, and ten maniples of sixty men each,—making in all three thousand heavy-armed troops. There were also twelve hundred light-armed troops, not organized in maniples. The whole number of men in a legion was therefore forty-two hundred. To each legion was usually joined a body of cavalry, numbering three hundred men. After the reduction of Latium and Italy, the allied cities were also obliged to furnish a certain number of men, according to the terms of the treaty. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT ROMAN WEAPONS factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ARMOR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN BATTLE TACTICS: STRATEGY, MANEUVERS, FORMATIONS, SIEGES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN FRONTIER DEFENSES: FORTS, WALLS, PURPOSES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ARMY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ORGANIZATION OF THE ANCIENT ROMAN MILITARY: UNITS, STRUCTURE, DIVISIONS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN LEGIONS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SOLDIERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE: TYPES, DUTIES AND REWARDS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Logistics of the Roman Army at War” by Jonathan Roth (1999) Amazon.com

“De Re Militari” by Vegetius, a 5th Century training manual in organization, weapons and tactics, as practiced by the Roman Legions Amazon.com

“Caesar's Great Success: Sustaining the Roman Army on Campaign” by Alexander Merrow , Agostino von Hassell, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Brill’s Companion to Diet and Logistics in Greek and Roman Warfare” by John F. Donahue and Lee L. Brice (2023) Amazon.com;

“Exploratio: Military & Political Intelligence in the Roman World from the Second Punic War to the Battle of Adrianople” by N. J. E. Austin and N. B. Rankov (1998) Amazon.com;

“Roman Battle Tactics, 109 BC-AD 313" by Ross Cowan (2007) Amazon.com

“Roman Cavalry Tactics” by M.C. Bishop and Adam Hook Amazon.com;

Ancient Siege Warfare: Persians, Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans 546–146 BC” by Duncan B Campbell and Adam Hook (2005) Amazon.com;

“Roman Warfare” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2000) Amazon.com

“Roman Military Equipment: From the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome” by M. C Bishop (1989) Amazon.com

“The Roman Army at War: 100 BC-AD 200" by Adrian Goldsworthy (1996) Amazon.com

“In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2003) Amazon.com

“The Complete Roman Army” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2003) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Army” (Blackwell) by Paul Erdkamp (2007) Amazon.com

“The Roman Army: The Greatest War Machine of the Ancient World” by Chris McNab 2010) Amazon.com

“Legions of Rome: The Definitive History of Every Imperial Roman Legion” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2010) Amazon.com

“Caesar's Legion: The Epic Saga of Julius Caesar's Elite Tenth Legion and the Armies of Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2002) Amazon.com

“Nero's Killing Machine: The True Story of Rome's Remarkable 14th Legion” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2005) Amazon.com

“The Praetorian Guard: A History of Rome's Elite Special Forces” by Sandra Bingham (2012) Amazon.com

“The Roman Cavalry” by Karen Dixon and Pat Southern (1992) Amazon.com

“Roman Cavalry Tactics” by M.C. Bishop and Adam Hook Amazon.com;

Drawing up a Legion in Order of Battle

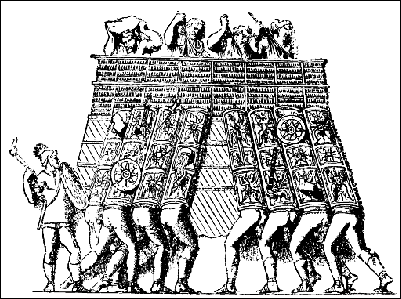

Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450) wrote in “De Re Militari” (“Military Institutions of the Romans”): “We shall exemplify the manner of drawing up an army in order of battle in the instance of one legion, which may serve for any number. The cavalry are posted on the wings. The infantry begin to form on a line with the :first cohort on the right. The second cohort draws up on the left of the first; the third occupies the center; the fourth is posted next; and the fifth closes the left flank. The ordinarii, the other officers and the soldiers of the first line, ranged before and round the ensigns, were called the principes. They were all heavy armed troops and had helmets, cuirasses, greaves, and shields. Their offensive weapons were large swords, called spathae, and smaller ones called semispathae together with five loaded javelins in the concavity of the shield, which they threw at the first charge. They had likewise two other javelins, the largest of which was composed of a staff five feet and a half long and a triangular head of iron nine inches long. This was formerly called the pilum, but now it is known by the name of spiculum. The soldiers were particularly exercised in the use of this weapon, because when thrown with force and skill it often penetrated the shields of the foot and the cuirasses of the horse. The other javelin was of smaller size; its triangular point was only five inches long and the staff three feet and one half. It was anciently called verriculum but now verutum. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001) ]

“The first line, as I said before, was composed of the principes; the hastati formed the second and were armed in the same manner. In the second line the sixth cohort was posted on the right flank, with the seventh on its left; the eighth drew up in the center; the ninth was the next; and the tenth always closed the left flank. In the rear of these two lines were the ferentarii, light infantry and the troops armed with shields, loaded javelins, swords and common missile weapons, much in the same manner as our modern soldiers. This was also the post of the archers who had helmets, cuirasses, swords, bows and arrows; of the slingers who threw stones with the common sling or with the fustibalus; and of the tragularii who annoyed the enemy with arrows from the manubalistae or arcubalistae.

“In the rear of all the lines, the triarii, completely armed, were drawn up. They had shields, cuirasses, helmets, greaves, swords, daggers, loaded javelins, and two of the common missile weapons. They rested during the acnon on one knee, so that if the first lines were obliged to give way, they might be fresh when brought up to the charge, and thereby retrieve what was lost and recover the victory. All the ensigns though, of the infantry, wore cuirasses of a smaller sort and covered their helmets with the shaggy skins of beasts to make themselves appear more terrible to the enemy. But the centurions had complete cuirasses, shields, and helmets of iron, the crest of which, placed transversely thereon, were ornamented with silver that they might be more easily distinguished by their respective soldiers.

“The following disposition deserves the greatest attention. In the beginning of an engagement, the first and second lines remained immovable on their ground, and the trairii in their usual positions. The light-armed troops, composed as above mentioned, advanced in the front of the line, and attacked the enemy. If they could make them give way, they pursued them; but if they were repulsed by superior bravery or numbers, they retired behind their own heavy armed infantry, which appeared like a wall of iron and renewed the action, at first with their missile weapons, then sword in hand. If they broke the enemy they never pursued them, least they should break their ranks or throw the line into confusion, and lest the enemy, taking advantage of their disorder, should return to the attack and destroy them without difficulty. The pursuit therefore was entirely left to the light-armed troops and the cavalry. By these precautions and dispositions the legion was victorious without danger, or if the contrary happened, was preserved without any considerable loss, for as it is not calculated for pursuit, it is likewise not easily thrown into disorder.

Roman Marches in the Neighborhood of the Enemy

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari”: “It is asserted by those who have made the profession their study that an army is exposed to more danger on marches than in battles. In an engagement the men are properly armed, they see their enemies before them and come prepared to fight. But on a march the soldier is less on his guard, has not his arms always ready and is thrown into disorder by a sudden attack or ambuscade. A general, therefore, cannot be too careful and diligent in taking necessary precautions to prevent a surprise on the march and in making proper dispositions to repulse the enemy, in case of such accident, without loss. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001) ]

from Trajan's Column

“In the first place, he should have an exact description of the country that is. the seat of war, in which the distances of places specified by the number of miles, the nature of the roads, the shortest routes, by-roads, mountains and rivers, should be correctly inserted. We are told that the greatest generals have carried their precautions on this head so far that, not satisfied with the simple description of the country wherein they were engaged, they caused plans to be taken of it on the spot, that they might regulate their marches by the eye with greater safety. A general should also inform himself of all these particulars from persons of sense and reputation well acquainted with the country by examining them separately at first, and then comparing their accounts in order to come at the truth with certainty.

“If any difficulty arises about the choice of roads, he should procure proper and skillful guides. He should put them under a guard and spare neither promises nor threat to induce them to be faithful. They will acquit themselves well when they know it is impossible to escape and are certain of being rewarded for their fidelity or punished for their perfidy. He must be sure of their capacity and experience, that the whole army be not brought into danger by the errors of two or three persons. For sometimes the common sort of people imagine they know what they really do not, and through ignorance promise more than they can perform.

“But of all precautions the most important is to keep entirely secret which way or by what route the army is to march. For the security of an expedition depends on the concealment of all motions from the enemy. The figure of the Minotaur was anciently among the legionary ensigns, signifying that this monster, according to the fable, was concealed in the most secret recesses and windings of the labyrinth, just as the designs of a general should always be impenetrable. When the enemy has no intimation of a march, it is made with security; but as sometimes the scouts either suspect or discover the decampment, or traitors or deserters give intelligence thereof, it will be proper to mention the method of acting in case of an attack on the march.

“The general, before he puts his troops in motion, should send out detachments of trusty and experienced soldiers well mounted, to reconnoiter the places through which he is to march, in front, in rear, and on the right and left, lest he should fall into ambuscades. The night is safer and more advantageous for your spies to do their business in than day, for if they are taken prisoners, you have, as it were, betrayed yourself. After this, the cavalry should march off first, then the infantry; the baggage, bat horses, servants and carriages follow in the center; and part of the best cavalry and infantry come in the rear, since it is oftener attacked on a march than the front. The flanks of the baggage, exposed to frequent ambuscades, must also be covered with a sufficient guard to secure them. But above all, the part where the enemy is most expected must be reinforced with some of the best cavalry, light infantry and foot archers.

relief rom Septimis Arch

Roman Defenses Against Enemy Troops

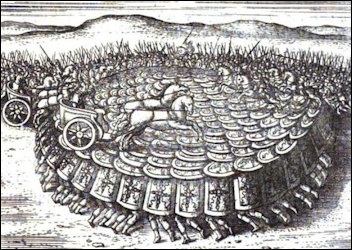

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari”: “If surrounded on all sides by the enemy, you must make dispositions to receive them wherever they come, and the soldiers should be cautioned beforehand to keep their arms in their hands, and to be ready in order to prevent the bad effects of a sudden attack. Men are frightened and thrown into disorder by sudden accidents and surprises of no consequence when foreseen. The ancients were very careful that the servants or followers of the army, if wounded or frightened by the noise of the action, might not disorder the troops while engaged, and also to prevent their either straggling or crowding one another too much, which might incommode their own men and give advantage to the enemy. They ranged the baggage, therefore, in the same manner as the regular troops under particular ensigns. They selected from among the servants the most proper and experienced and gave them the command of a number of servants and boys, not exceeding two hundred, and their ensigns directed them where to assemble the baggage. Proper intervals should always be kept between the baggage and the troops, that the latter may not be embarrassed for want of room in case of an attack during the march. The manner and disposition of defense must be varied according to the difference of ground. In an open country you are more liable to be attacked by horse than foot. But in a woody, mountainous or marshy situation, the danger to be apprehended is from foot. Some of the divisions being apt through negligence to move too fast, and others too slow, great care is to be taken to prevent the army from being broken or from running into too great a length, as the enemy would instantly take advantage of the neglect and penetrate without difficulty. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

“The tribunes, their lieutenants or the masters at arms of most experience, must therefore be posted at proper distances, in order to halt those who advance too fast and quicken such as move too slow. The men at too great a distance in the front, on the appearance of an enemy, are more disposed to fly than to join their comrades. And those too far behind, destitute of assistance, fall a sacrifice to the enemy and their own despair. The enemy, it may be concluded, will either plant ambuscades or make his attack by open force, according to the advantage of the ground. Circumspection in examining every place will be a security against concealed danger; and an ambuscade, if discovered and promptly surrounded, will return the intended mischief with interest.

“If the enemy prepare to fall upon you by open force in a mountainous country, detachments must be sent forward to occupy the highest eminences, so that on their arrival they may not dare to attack you under such a disadvantage of ground, your troops being posted so much above theIr and presenting a front ready for their reception. It is better to send men forward with hatchets and other tools in order to open ways that are narrow but safe, without regard to the labor, rather than to run any risk in the finest roads. It is necessary to be well acquainted whether the enemy usually make their attempts in the night, at break of day or in the hours of refreshment or rest; and by knowledge of their customs to guard against what we find their general practice. We must also inform ourselves whether they are strongest in infantry or cavalry; whether their cavalry is chiefly armed with lances or with bows; and whether their principal strength consists in their numbers or the excellence of their arms. All of this will enable us to take the most proper measures to distress them and for our advantage. When we have a design in view, we must consider whether it will be most advisable to begin the march by day or by night; we must calculate the distance of the places we want to reach; and take such precautions that in summer the troops may not suffer for want of water on their march, nor be obstructed in winter by impassable morasses or torrents, as these would expose the army to great danger before it could arrive at the place of its destination. As it highly concerns us to guard against these inconveniences with prudence, so it would be inexcusible not to take advantage of an enemy that fell into them through ignorance or negligence. Our spies should be constantly abroad; we should spare no pains in tampering with their men, and give all manner of encouragement to deserters. By these means we may get intelligence of their present or future designs. And we should constantly keep in readiness some detachments of cavalry and light infantry, to fall upon them when they least expect it, either on the march, or when foraging or marauding.

Roman policy for engagement

Roman Battle Planning and Decision-Making

Cristian Violatti of Listverse wrote: “During the times of the Roman Republic, only the Senate, considered the governmental entity that embodied the will of Roman citizens, was entitled to declare war. As Rome expanded and the power of its generals grew larger, some wars were declared by the Roman generals without senatorial approval. An example of this was the war against Mithridates of Pontus, which was declared in 89 B.C. by the consul and general Manius Aquillius without any involvement from the Senate. This was illegal in theory, but in practice, there was little the Senate could do. Some generals were just too powerful. When Rome became an empire, the decision of going to war became the emperor’s responsibility alone. [Source: Cristian Violatti, Listverse, September 4, 2016 ]

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari”: “A battle is commonly decided in two or three hours, after which no further hopes are left for the worsted army. Every plan, therefore, is to be considered, every expedient tried and every method taken before matters are brought to this last extremity. Good officers decline general engagements where the danger is common, and prefer the employment of stratagem and finesse to destroy the enemy as much as possible in detail and intimidate them without exposing our own forces.

“I shall insert some necessary instructions on this head collected from the ancients. It is the duty and interest of the general frequently to assemble the most prudent and experienced officers of the different corps of. the army and consult with them on the state both of his own and the enemy's forces. All overconfidence, as most pernicious in its consequences, must be banished from the deliberations. He must examine which has the superiority in numbers, whether his or the adversary's troops are best armed, which are in the best condition, best disciplined and most resolute in emergencies. The state of the cavalry of both armies must be inquired into, but more especially that of the infantry, for the main strength of an army consists of the latter. With respect to the cavalry, he must endeavor to find out in which are the greatest numbers of archers or of troopers armed with lances, which has the most cuirassiers and which the best horses. Lastly he must consider the field of battle and to judge whether the ground is more advantageous for him or his enemy. If strongest in cavalry, we should prefer plains and open ground; if superior in infantry, we should choose a situation full of enclosures, ditches, morasses and woods, and sometimes mountainous. Plenty or scarcity in either army are considerations of no small importance, for famine, according to the common proverb, is an internal enemy that makes more havoc than the sword. But the most material article is to determine whether it is most proper to temporize or to bring the affair to a speedy decision by action. The enemy sometimes expect an expedition will soon be over; and if it is protracted to any length, his troops are either consumed by want,. induced to return home by the desire of seeing their families or, having done nothing considerable in the field, disperse themselves from despair of success. Thus numbers, tired out with fatigue and disgusted with the service, desert, others betray them and many surrender themselves. Fidelity is seldom found in troops disheartened by misfortunes. And in such case an army which was numerous on taking the field insensibly dwindles away to nothing.

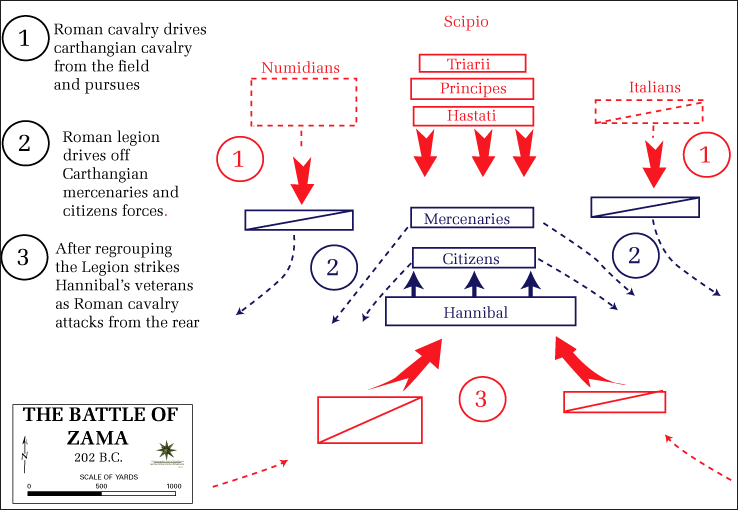

Roman army battle position in the Roman victory over the Catharginians at Zama

“It is essential to know the character of the enemy and of their principal officers-whether they be. rash or cautious, enterprising or timid, whether they fight on principle or from chance and whether the nations they have been engaged with were brave or cowardly. We must know how far to depend upon the fidelity and strength of auxiliaries, how the enemy's troops and our own are affected and which appear most confident of success, a consideration of great effect in raising or depressing the courage of an army. A harangue from the general, especially if he seems under no apprehension himself, may reanimate the soldiers if dejected. Their spirits revive if any considerable advantage is gained either by stratagem or otherwise, if the fortune of the enemy begins to change or if you can contrive to beat some of their weak or poorly-armed detachments.

“But you must by no means venture to lead an irresolute or diffident army to a general engagement. The difference is great whether your troops are raw or veterans, whether inured to war by recent service or for some years unemployed. For soldiers unused to fighting for a length of time must be considered in the same light as recruits. As soon as the legions, auxiliaries and cavalry are assembled from their several quarters, it is the duty of a good general to have every corps instructed separately in every part of the drill by tribunes of known capacity chosen for that purpose. He should afterwards form them into one body and train them in all the maneuvers of the line as for a general action. He must frequently drill them himself to try their skill and strength, and to see whether they perform their evolutions with proper regularity and are sufficiently attentive to the sound of the trumpets, the motions of the colors and to his own orders and signals. If deficient in any of these particulars, they must be instructed and exercised till perfect.

“But though thoroughly disciplined and complete in their field exercises, in the use of the bow and javelin, and in the evolutions of the line, it is not advisable to lead them rashly or immediately to battle. A favorable opportunity must be watched for, and they must first be prepared by frequent skirmishes and slight encounters. Thus a vigilant and prudent general will carefully weigh in his council the state of his own forces and of those of the enemy, just as a civil magistrate judging between two contending parties. If he finds himself in many respects superior to his adversary, he must by no means defer bringing on an engagement. But if he knows himself inferior, he must avoid general actions and endeavor to succeed by surprises, ambuscades and stratagems. These, when skillfully managed by good generals, have often given them the victory over enemies superior both in numbers and strength.

Preventing Mutinies and Managing Raw and Undisciplined Troops

Cristian Violatti of Listverse wrote: “Mutiny of the troops was always a potential issue for Roman generals, and there were many policies in place to discourage this type of behavior. Punishment by decimation (decimatio) was arguably the most feared and effective. It involved the beating or stoning to death of every 10th man within the army unit where mutiny took place. The victims were chosen by lot by their own colleagues. Whenever a group within the army was planning a mutiny, the prospect of decimation made them think twice and they were likely to be reported by their own colleagues. [Source: Cristian Violatti, Listverse, September 4, 2016 ]

“The Romans knew that decimation, although effective, was also unjust because many of the actual victims might not have had anything to do with the mutiny. From the standpoint of the Romans, the unfairness of decimation was a necessary evil. Tacitus (Annals 14.44) wrote, “Setting an example on a large scale always involves a degree of injustice when individuals suffer to ensure the public good.” (McKeown 2010: 40-41)

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari”: “It is indispensably necessary for those engaged in war not only to instruct them in the means of preserving their own lives, but how to gain the victory over their enemies.A commander-in-chief therefore, whose power and dignity are so great and to whose fidelity and bravery the fortunes of his countrymen, the defense of their cities, the lives of the soldiers, and the glory of the state, are entrusted, should not only consult the good of the army in general, but extend his care to every private soldier in it. For when any misfortunes happen to those under his command, they are considered as public losses and imputed entirely to his misconduct. If therefore he finds his army composed of raw troops or if they have long been unaccustomed to fighting, he must carefully study the strength, the spirit, the manners of each particular legion, and of each body of auxiliaries, cavalry and infantry. He must know, if possible, the name and capacity of every count, tribune, subaltern and soldier. He must assume the most respectable authority and maintain it by severity. He must punish all military crimes with the greatest rigor of the laws. He must have the character of being inexorable towards offenders and endeavor to give public examples thereof in different places and on different occasions. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

“Having once firmly established these regulations, he must watch the opportunity when the enemy, dispersed in search of plunder, think themselves in security, and attack them with detachments of tried cavalry or infantry, intermingled with young soldiers, or such as are under the military age. The veterans will acquire fresh experience and the others will be inspired with courage by the advantages such opportunities will give him. He should form ambuscades with the greatest secrecy to surprise the enemy at the passages of rivers, in the rugged passes of mountains, in defiles in woods and when embarrassed by morasses or difficult roads. He should regulate his march so as to fall upon them while taking their refreshments or sleeping, or at a time when they suspect no dangers and are dispersed, unarmed and their horses unsaddled. He should continue these kinds of encounters till his soldiers have imbibed a proper confidence in themselves. For troops that have never been in action or have not for some time been used to such spectacles, are greatly shocked at the sight of the wounded and dying; and the impressions of fear they receive dispose them rather to fly than fight.

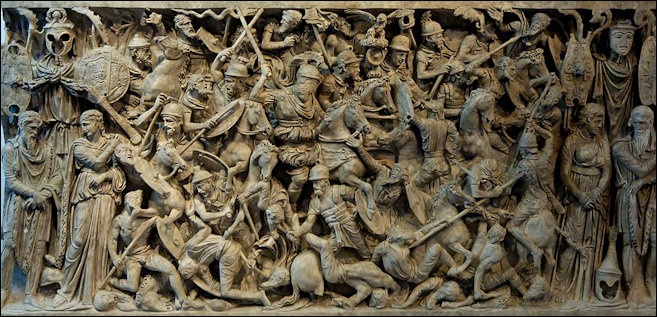

barbarians attacking on a Roman sarcophagus

“If the enemy makes excursions or expeditions, the general should attack him after the fatigue of a long march, fall upon him unexpectedly, or harass his rear. He should detach parties to endeavor to carry off by surprise any quarters established at a distance from the hostile army for the convenience of forage or provisions. F or such measures should be pursued at first as can produce no very bad effects if they should happen to miscarry, but would be of great advantage if attended with success. A prudent general will also try to sow dissention among his adversaries, for no nation, though ever so weak in itself can be completely ruined by its enemies unless its fall be facilitated by its own distraction. In civil dissensions men are so intent on the destruction of their private enemies that they are entirely regardless of the public safety.

“One maxim must be remembered throughout this work: that no one should ever despair of effecting what has been already performed. It may be said that our troops for many years past have not even fortified their permanent camps with ditches, ramparts or palisades. The answer is plain. If those precautions had been taken, our armies would never have suffered by surprises of the enemy both by day and night. The Persians, after the example of the old Romans, surround their camps with ditches and, as the ground in their country is generally sandy, they always carry with them empty bags to fill with the sand taken out of the trenches and raise a parapet by piling them one on the other. All the barbarous nations range their carriages round them in a circle, a method which bears some resemblance to a fortified camp. They thus pass their nights secure from surprise.

“Are we afraid of not being able to learn from others what they before have learned from us? At present all this is to be found in books only, although formerly constantly practiced. Inquiries are now no longer made about customs that have been so long neglected, because in the midst of peace, war is looked upon as an object too distant to merit consideration. But former instances will convince us that the reestablishment of ancient discipline is by no means impossible, although now so totally lost.

“In former ages the art of war, often neglected and forgotten, was as often recovered from books and reestablished by the authority and attention of our generals. Our armies in Spain, when Scipio Africanus took the command, were in bad order and had often been beaten under preceding generals. He soon reformed them by severe discipline and obliged them to undergo the greatest fatigue in the different military works, reproaching them that since they would not wet their hands with the blood of their enemies, they should soil them with the mud of the trenches. In short, with these very troops he afterwards took the city of Numantia and burned it to the ground with such destruction of its inhabitants that not one escaped. In Africa an army, which under the command of Albinus had been forced to pass under the yoke, was by Metellus brought into such order and discipline, by forming it on the ancient model, that they afterwards vanquished those very enemies who had subjected them to that ignominious treatment. The Cimbri defeated the legions of Caepio, Manilus and Silanus in Gaul, but Marius collected their shattered remnants and disciplined them so effectually that he destroyed an innumerable multitude of the Cimbri, Teutones and Ambrones in one general engagement. Nevertheless it is easier to form young soldiers and inspire them with proper notions of honor than to reanimate troops who have been once disheartened.”

soldiers making sacrifices

Roman Preparations for Battle and Gaging Morale

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari” (“Military Institutions of the Romans”): “Having explained the less considerable branches of the art of war, the order of military affairs naturally leads us to the general engagement. This is a conjuncture full of uncertainty and fatal to kingdoms and nations, for in the decision of a pitched battle consists the fulness of victory. This eventuality above all others requires the exertion of all the abilities of a general, as his good conduct on such an occasion gains him greater glory, or his dangers expose him to greater danger and disgrace. This is the moment in which his talents, skill and experience show themselves in their fullest extent. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

“Formerly to enable the soldiers to charge with greater vigor, it was customary to order them a moderate refreshment of food before an engagement, so that their strength might be the better supported during a long conflict. When the army is to march out of a camp or city in the presence of their enemies drawn up and ready for action, great precaution must be observed lest they should be attacked as they defile from the gates and be cut to pieces in detail. Proper measures must therefore be taken so that the whole army may be clear of the gates and form in order of battle before the enemy's approach. If they are ready before you can have quitted the place, your design of marching out must either be deferred till another opportunity or at least dissembled, so that when they begin to insult you on the supposition that you dare not appear, or think of nothing but plundering or returning and no longer keep their ranks, you may sally out and fall upon them while in confusion and surprise. Troops must never be engaged in a general action immediately after a long march, when the men are fatigued and the horses tired. The strength required for action is spent in the toil of the march. What can a soldier do who charges when out of breath? The ancients carefully avoided this inconvenience, but in later times some of our Roman generals, to say nothing more, have lost their armies by unskillfully neglecting this precaution. Two armies, one tired and spent, the other fresh and in full vigor, are by no means an equal match.

“It is necessary to know the sentiments of the soldiers on the day of an engagement. Their confidence or apprehensions are easily discovered by their looks, their words, their actions and their motions. No great dependence is to be placed on the eagerness of young soldiers for action, for fighting has something agreeable in the idea to those who are strangers to it. On the other hand, it would be wrong to hazard an engagement, if the old experienced soldiers testify to a disinclination to fight. A general, however, may encourage and animate his troops by proper exhortations and harangues, especially if by his account of the approaching action he can persuade them into the belief of an easy victory. With this view, he should lay before them the cowardice or unskillfulness of their enemies and remind them of any former advantages they may have gained over them. He should employ every argument capable of exciting rage, hatred and indignation against the adversaries in the minds of his soldiers.

“It is natural for men in general to be affected with some sensations of fear at the beginning of an engagement, but there are without doubt some of a more timorous disposition who are disordered by the very sight of the enemy. To diminish these apprehensions before you venture on action, draw up your army frequently in order of battle in some safe situation, so that your men may be accustomed to the sight and appearance of the enemy. When opportunity offers, they should be sent to fall upon them and endeavor to put them to flight or kill some of their men. Thus they will become acquainted with their customs, arms and horses. And the objects with which we are once familiarized are no longer capable of inspiring us with terror.”

site of the Teutoburg Forest battle, where the Romans got hammered by Germans

Roman Ideas on Choosing Battlefield Sites and Organizing Troops

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari”: “Choice of the Field of Battle: Good generals are acutely aware that victory depends much on the nature of the field of battle. When you intend therefore to engage, endeavor to draw the chief advantage from your situation. The highest ground is reckoned the best. Weapons thrown from a height strike with greater force; and the party above their antagonists can repulse and bear them down with greater impetuosity, while they who struggle with the ascent have both the ground and the enemy to contend with. There is, however, this difference with regard to place: if you depend on your foot against the enemy's horse, you must choose a rough, unequal and mountainous situation. But if, on the contrary, you expect your cavalry to act with advantage against the enemy's infantry, your ground must indeed be higher, but plain and open, without any obstructions of woods or morasses. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

“Order of Battle: In drawing up an army in order of battle, three things are to be considered: the sun, the dust and the wind. The sun in your face dazzles the sight: if the wind is against you, it turns aside and blunts the force of your weapons, while it assists those of your adversary; and the dust driving in your front fills the eyes of your men and blinds them. Even the most unskillful endeavor to avoid these inconveniences in the moment of making their dispositions; but a prudent general should extend his views beyond the present; he should talke such measures as not to be incommoded in the course of the day by different aspects of the sun or by contrary winds which often rise at a certain hour and might be detrimental during action. Our troops should be so disposed as to have these inconveniences behind them, while they are directly in the enemy's front.

“Proper Distances and Intervals: Having explained the general disposition of the lines, we now come to the distances and dimensions. One thousand paces contain a single rank of one thousand six hundred and fifty-six foot soldiers, each man being allowed three feet. Six ranks drawn up on the same extent of ground will require nine thousand nine hundred and ninety-six men. To form only three ranks of the same number will take up two thousand paces, but it is much better to increase the number of ranks than to make your front too extensive. We have before observed the distance between each rank should be six feet, one foot of which is taken up by the men. Thus if you form a body of ten thousand men into six ranks they will occupy thirty-six feet. in depth and a thousand paces in front. By this calculation it is easy to compute the extent of ground required for twenty or thirty thousand men to form upon. Nor can a general be mistaken when thus he knows the proportion of ground for any fixed number of men.

“But if the field of battle is not spacious enough or your troops are very numerous, you may form them into nine ranks or even more, for it is more advantageous to engage in close order that to extend your line too much. An army that takes up too much ground in front and too little in depth, is quickly penetrated by the enemy's first onset. After this there is no remedy. As to the post of the different corps in the right or left wing or in the center, it is the general rule to draw them up according to their respective ranks or to distribute them as circumstances or the dispositions of the enemy may require.”

troop placements when the Roman generals Caesar and Pompey faced off against each other

Roman Views on Troop Placement

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari”: “The line of infantry being formed, the cavalry are drawn up in the wings. The heavy horse, that is, the cuirassiers and troopers armed with lances, should join the infantry. The light cavalry, consisting of the archers and those who have no cuirasses, should be placed at a greater distance. The best and heaviest horse are to cover the flanks of the foot, and the light horse are posted as abovementioned to surround and disorder the enemy's wings. A general should know what part of his own cavalry is most proper to oppose any particular squadrons or troops of the enemy. For from some causes not to be accounted for some particular corps fight better against others, and those who have defeated superior enemies are often overcome by an inferior force. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

“If your cavalry is not equal to the enemy's it is proper, after the ancient custom, to intermingle it with light infantry armed with small shields and trained to this kind of service. By observing this method, even though the flower of the enemy's cavalry should attack you, they will never be able to cope with this mixed disposition. This was the only resource of the old generals to supply the defects of their cavalry, and they intermingled the men, used to running and armed for this purpose with light shields, swords and darts, among the horse, placing one of them between two troopers.

“Reserves: The method of having bodies of reserves in rear of the army, composed of choice infantry and cavalry, commanded by the supernumerary lieutenant generals, counts and tribunes, is very judicious and of great consequence towards the gaining of a battle. Some should be posted in rear of the wings and some near the center, to be ready to fly immediately to the assistance of any part of the line which is hard pressed, to prevent its being pierced, to supply the vacancies made therein during the action and thereby to keep up the courage of their fellow soldiers and check the impetuosity of the enemy. This was an invention of the Lacedaemonians [Spartans] , in which they were imitated by the Carthaginians. The Romans have since observed it, and indeed no better disposition can be found.

“The line is solely designed to repulse, or if possible, break the enemy. If it is necessary to form the wedge or the pincers, it must be done by the supernumerary troops stationed in the rear for that purpose. If the saw is to be formed, it must also be done from the reserves, for if once you begin to draw off men from the line you throw all into confusion. If any flying platoon of the enemy should fall upon your wing or any other part of your army, and you have no supernumerary troops to oppose it or if you pretend to detach either horse or foot from your line for that service by endeavoring to protect one part, you will expose the other to greater danger. In armies not very numerous, it is much better to contract the front, and to have strong reserves. In short, you must have a reserve of good and well-armed infantry near the center to form the wedge and thereby pierce the enemy's line; and also bodies of cavalry armed with lances and cuirasses, with light infantry, near the wings, to surround the flanks of the enemy.

Resources in Case of Defeat

granary at Vindolanda fort

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari”: “If while one part of your army is victorious the other should be defeated, you are by no means to despair, since even in this extremity the constancy and resolution of a general may recover a complete victory. There are innumerable instances where the party that gave least way to despair was esteemed the conqueror. For where losses and advantages seem nearly equal, he is reputed to have the superiority who bears up against his misfortunes with greatest resolution. He is therefore to be first, if possible, to seize the spoils of the slain and to make rejoicings for the victory. Such marks of confidence dispirit the enemy and redouble your own courage. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

“Yet notwithstanding an entire defeat, all possible remedies must be attempted, since many generals have been fortunate enough to repair such a loss. A prudent officer will never risk a general action without taking such precautions as will secure him from any considerable loss in case of a defeat, for the uncertainty of war and the nature of things may render such a misfortune unavoidable. The neighborhood of a mountain, a fortified post in the rear or a resolute stand made by a good body of troops to cover the retreat, may be the means of saving the army.

“An army after a defeat has sometimes rallied, returned on the enemy, dispersed him by pursuing in order and destroyed him without difficulty. Nor can men be in a more dangerous situation than, when in the midst of joy after victory, their exultation is suddenly converted into terror. Whatever be the event, the remains of the army must be immediately assembled, reanimated by suitable exhortations and furnished with fresh supplies of arms. New levies should immediately be made and new reinforcements provided. And it is of much the greatest consequence that proper opportunities should be taken to surprise the victorious enemies, to draw them into snares and ambuscades and by this means to recover the drooping spirits of your men. Nor will it be difficult to meet with such opportunities, as the nature of the human mind is apt to be too much elated and to act with too little caution in prosperity. If anyone should imagine no resource is left after the loss of a battle, let him reflect on what has happened in similar cases and he will find that they who were victorious in the end were often unsuccessful in the beginning.

Maxims from De Re Militari

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari”: “It is the nature of war that what is beneficial to you is detrimental to the enemy and what is of service to him always hurts you. It is therefore a maxim never to do, or to omit doing, anything as a consequence of his actions, but to consult invariably your own interest only. And you depart from this interest whenever you imitate such measures as he pursues for his benefit. For the same reason it would be wrong for him to follow such steps as you take for your advantage. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

“The more your troops have been accustomed to camp duties on frontier stations and the more carefully they have been disciplined, the less danger they will be exposed to in the field.

“Men must be sufficiently tried before they are led against the enemy.

“It is better to have several bodies of reserves than to extend your front too much.

“A general is not easily overcome who can form a true judgment of his own and the enemy's forces.

“Few men are born brave; many become so through care and force of discipline.

“An army is strengthened by labor and enervated by idleness.

“Troops are not to be led to battle unless confident of success.

“An army unsupplied with grain and other necessary provisions will be vanquished without striking a blow.

“If your left wing is strongest, you must attack the enemy's right according to the third formation.

“When an enemy's spy lurks in the camp, order all your soldiers in the day time to their tents, and he will instantly be apprehended.

“On finding the enemy has notice of your designs, you must immediately alter your plan of operations.

“Consult with many on proper measures to be taken, but communicate the plans you intend to put in execution to few, and those only of the most assured fidelity; or rather trust no one but yourself.

“Punishment, and fear thereof, are necessary to keep soldiers in order in quarters; but in the field they are more influenced by hope and rewards.

“This abridgment of the most eminent military writers, invincible Emperor, contains the maxims and instructions they have left us, approved by different ages and confirmed by repeated experience. The Persians admire your skill in archery; the Huns and Alans endeavor in vain to imitate your dexterity in horsemanship; the Saracens and Indians cannot equal your activity in the hunt; and even the masters at arms pique themselves on only part of that knowledge and expertness of which you give so many instances in their own profession. How glorious it is therefore for Your Majesty with all these qualifications to unite the science of war and the art of conquest, and to convince the world that by Your conduct and courage You are equally capable of performing the duties of the soldier and the general!

Roman Spies

Ben Macintyre of the Times of London wrote: “The Greek word for spook is the pleasingly anagrammatical skopos, and spies appear throughout Greek literature. In 405BC, for example, a Spartan spy at Aegospotami reported that the Athenians had failed to post a guard on the fleet, which was consequently attacked and destroyed. Like us, the Romans imagined they were too noble for the murky business of spying; but they came to accept that without a centralised intelligence system the future of the empire was in jeopardy. [Source: Ben Macintyre, Times of London, October 9, 2010]

Julius Caesar came, saw and conquered; and before that, he spied — rather inadequately. In 55BC, the Romans were suffering from what would now be called a critical intelligence deficit. Caesar wanted to invade Britain but knew very little about the inhospitable island off the coast of Gaul. So Caesar launched a covert operation to gather information on British customs, harbours and military tactics. Caesar's first invasion was a failure, in large part because of inadequate and faulty intelligence. His internal spies used advanced techniques, including codes and ciphers, but he never did quite get the hang of intelligence.Moments before he was assassinated, a list of the conspirators was thrust into his hand, but he failed to act swiftly enough, and did not live to regret it.

Instead of sending out covert agents to report on neighbouring tribes, until about AD100 the Romans preferred to rely on huge defences, ad hoc military scouting in enemy territory and fides Romana, mutual trust between Rome and its allies, which sent word if barbarians approached. There was no lack of domestic espionage inside Rome: every aristocrat had a private network of agents and informers. Not until the 2nd century AD did Rome organise an agency that might be called a secret service. These were the frumentarii, ancestors of the CIA, KGB and MI6.

A cadre of supply sergeants whose original function was to collect and distribute grain, they combined the roles of tax collector, courier, secret policeman, political assassin and spy, and were generally loathed. Emperor Diocletian eventually disbanded the frumentarii, but they were immediately replaced by the agentes in rebus (general agents, a deliberately vague title), responsible for internal security and external intelligence. Their task, as defined by Procopius, was to "gain the most speedy information concerning the movements of the enemy, seditions . . . and the actions of governors and other officials".

The Romans were as suspicious of the spy trade as we are, yet as the Roman world became increasingly unpredictable the future of that civilisation came to rest, in part, on the provision of good intelligence. Then, as now, spies occupied a contradictory position in society, feared but oddly glamorous, liable to corruption, regarded with mistrust by their political overlords but necessary for the security of the state. The 4th-century philosopher Libanius described the agentes as "sheepdogs who have joined the wolf pack".

The toga-and-dagger skulduggery of I, Claudius may seem distant and encrusted by myth, but in many ways the challenges of espionage and intelligence-gathering in the ancient world are similar to those facing the West today: distributing resources between conventional warfare and covert operations, policing internal sedition and reconciling the conflicting demands of secrecy and liberty. An intelligence agent could have no better training than a solid grounding in classics, Jonathan Evans, director-general of the British overseas spy agency MI5 told Iris, a magazine promoting Latin teaching in state schools: "I think that Sulla would have found a soul mate in some of the security chiefs I have met from despotic regimes elsewhere in the world." Evans is a classics graduate who utilized the insights of the Roman poet Juvenal, historian Suetonius, and Sulla, the Roman general with "the cunning of a fox" in his fight against al-Qaida.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024