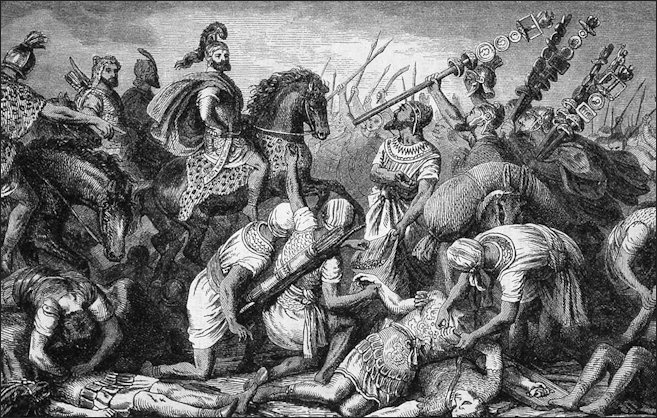

BATTLES BETWEEN CELTS AND ROMANS

Gauls in Rome

The Celts (Senones) attacked and captured Rome in 390 B.C. after the Battle of the Allia, fought at the confluence of the Tiber and Allia rivers 16 kilometers north of Rome. The Romans were routed and Rome was sacked but the Celts were unable to take the center of the city, at Campidoglio, the legend goes, because, a group of honking geese alerted the Roman of the nighttime Celtic attack.

The Celts lost a crucial battle to the Romans at Telamon, Italy in 225 B.C. Even though the Celts captured a Roman consul and waved his head on stake, their courageous but unruly hand-to-hand tactics were no match against the spears and disciplined ranks of the Romans.

To protect his army of 40,000 men from the Gauls in the 1st century B.C., Julius Caesar erected a fortress with a circumference of 20 kilometers. The fort was protected by hidden pits with upward-pointing sticks, logs spiked with iron hooks, walls fashioned from forked timbers and double ditches. The Celts hurled themselves bravely and foolishly at the fortress and were routed after the Roman cavalry charged down from a hill at a strategic time.

The confrontation between Caesar and the Gauls pitted 55,000 Romans against 250,000 Celts. In his eight-year campaign against the Celts in Gaul Caesar wrote he took 800 towns and killed 1,192,00 men, women and children in 30 battles. In one battle alone he reported his army slaughtered over 250,000 Helveteii, a tribe from present-day Switzerland.

Vercingetorix, the leader of the Celtic forces, surrendered himself at the feet the feet of Caesar who sent him to Rome where the Gaulic leader was imprisoned for six years and ultimately paraded through the streets and strangled in the Forum.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FAMOUS BATTLES OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE: ACTIUM TO CHALONS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN MILITARY: MOBILIZATION, INFRASTRUCTURE, SPOILS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN MILITARY HISTORY AND REFORMS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ORGANIZATION OF THE ANCIENT ROMAN MILITARY: UNITS, STRUCTURE, Divisions europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TRIUMPHS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ARMY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SAILORS, SHIPS AND THE ROMAN NAVY europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

href="https://amzn.to/4igMXFw"> Amazon.com

“Roman Warfare” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2000) Amazon.com

“Romans at War: The Roman Military in the Republic and Empire” by Simon Elliot (2020) Amazon.com

“Pax: War and Peace in Rome's Golden Age” by Tom Holland (2023) Amazon.com

“The Roman Army at War: 100 BC-AD 200" by Adrian Goldsworthy (1996) “Roman Republic at War: A Compendium of Roman Battles from 498 to 31 BC” by Don Taylor (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Conquest of Italy” by Jean-Michel David and Antonia Nevill (1996)

Amazon.com

“Caudine Forks 321 BC: Rome's Humiliation in the Second Samnite War” by Nic Fields, Seán Ó’Brógáin (Illustrator) Amazon.com;

“Rome's Third Samnite War, 298–290 BC: The Last Stand of the Linen Legion”

by Mike Roberts (2020) Amazon.com;

“Lake Trasimene 217 BC: Ambush and Annihilation of a Roman Army” by Nic Fields, Donato Spedaliere (Illustrator) (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Ghosts of Cannae: Hannibal and the Darkest Hour of the Roman Republic”

by Robert L. O'Connell (2011) Amazon.com;

“Cannae: Hannibal's Greatest Victory” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2001) Amazon.com

“Zama 202 BC: Scipio crushes Hannibal in North Africa” by Mir Bahmanyar and Peter Dennis (2016) Amazon.com;

“Hannibal's Last Battle: Zama & The Fall of Carthage” by Brian Todd Carey , Joshua B. Allfree , et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146BC” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Punic Wars 264–146 BC” by Nigel Bagnall (2002) Amazon.com

“The War with Hannibal” (Penguin Classics) by Livy Amazon.com

“Greece and Rome at War” by Peter Connolly (1981) Amazon.com;

“The Third Macedonian War and Battle of Pydna: Perseus' Neglect of Combined-arms Tactics and the Real Reasons for the Roman Victory” by Graham Wrightson (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy” by Adrienne Mayor (2009) Amazon.com

“The Conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Julius Caesar: The Complete Works : Gallic War, Civil War, Alexandrian War, African War, and Spanish War : in One Volume, with Maps, Annotations, Appendices, and Encyclopedic Index” by 2017) Amazon.com

“The Civil War of Caesar” (Penguin Classics) by Julius Caesar and Jane P. Gardner Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Civil War: 49–44 BC” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2023) Amazon.com;

“Pharsalus 48 BC: Caesar and Pompey – Clash of the Titans”, Illustrated, by Si Sheppard, Adam Hook, (2006) Amazon.com;

“The War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium” by Barry S. Strauss (2022) Amazon.com

Sacking of Rome by the Gauls (390 B.C.)

The Gauls (Celts, Senones) attacked and captured Rome in 390 B.C. after the Battle of the Allia, fought at the confluence of the Tiber and Allia rivers 16 kilometers north of Rome. The Romans were routed and Rome was sacked but the Celts were unable to take the center of the city, at Campidoglio, the legend goes, because, a group of honking geese alerted the Roman of the nighttime Gaulic attack.

If the capture of Veii was the greatest victory which the Romans had ever achieved, we now approach one of the greatest disasters which they ever suffered. One reason why Rome was able to capture Veii was the fact that the great body of the Etruscans were obliged to face a new enemy on the northern frontier, an enemy whom they feared more than the Romans on the south. This enemy was the Gauls, the barbarous nation which held the valley of the Po, and which now swept south across the Apennines like a hurricane. News of this invasion reached Rome, and it was resolved to aid the Etruscans in repelling the common foe.

Pyrrhus and his Elephants

The Roman army met the Gauls near the little river Allia, about eleven miles north of Rome, and suffered a terrible defeat. The Gauls pressed on to Rome. They entered, plundered, and burned the city. Only the Capitol remained. This was besieged for seven months, and, according to the legend, was at one time saved by M. Manlius, who was aroused by the cackling of the sacred geese just in time to resist a night assault. At last the Gauls, sated with plunder, and induced by a large bribe, retreated unmolested or, as one legend says, were driven from the city by Camillus, the hero of the Veientine war. The destruction of Rome by the Gauls was a great disaster, not only to Rome, but to all the world; because in it the records of the ancient city perished, leaving many things in the early history of ancient Rome dark and obscure. \~\

The Restoration of Rome: Such a disastrous event as the Gallic invasion would have disheartened almost any other people; but Rome bent before the storm and soon recovered after the tempest was past. Many of the people desired to abandon the city of ashes, and transfer their homes to the vacant town of Veii. But it was decided that Rome was the place for Romans. The city rose so quickly from its ruins that little care was taken in the work of rebuilding, so that the new streets were often narrow and irregular. \~\

The Romans seemed to be in haste to resume the work of extending their power, which had been so favorably begun with the conquest of Veii, but which had been interrupted by the defeat on the Allia. Rome raised new armies and quickly defeated her old enemies, the Volscians, Aequians, and Etruscans, who tried to take advantage of her present distress. The hero Camillus added fresh laurels to his fame. The southern part of Etruria was recovered, and its towns garrisoned by military colonies. Many towns of Latium also were brought into subjection, and they afforded homes for the poor people. Rome seemed almost ready to enter upon a career of conquest; but the recurrence of poverty and distress demanded the attention of the government, and showed the need of further reforms. \~\

See Separate Article: GAULS IN PRE-ROMAN AND EARLY REPUBLICAN ITALY europe.factsanddetails.com

War with Pyrrhus (280-275 B.C.)

Pyrrhus (319/318–272 BC) was a Greek general and statesman of the Hellenistic period. He was king of the Greek tribe of Molossians, of the royal Aeacid house (from c. 297 BC), and later he became king of Epirus (r. 306–302, 297–272 BC). He was one of the strongest opponents of early Rome. His battles, though victorious, caused him heavy losses, from which the term Pyrrhic victory was coined. He is the subject of one of Plutarch's Parallel Lives. [Source: Wikipedia]

Pyrrhus lands in Italy: Pyrrhus landed in Italy, bringing with him a mercenary army raised in different parts of Greece, consisting of twenty-five thousand men and twenty elephants. Tarentum was placed under the strictest military discipline. Rome, on her part, made the greatest preparations to meet the invader. Her garrisons were strengthened. One army was sent into Etruria, to prevent an uprising in the north; and the main army, under the consul Valerius Laevinus, was sent to southern Italy. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Battle of Heraclea (280 B.C.): The first battle between the Italian and Greek soldiers occurred at Heraclea, not far from Tarentum. It was here that the Roman legion first came into contact with the Macedonian phalanx. The legion was drawn up in three separate lines, in open order; and the soldiers, after hurling the javelins, fought at close quarters with the sword. The phalanx, on the other hand, was a solid mass of soldiers in close order, with their shields touching, and twenty or thirty ranks deep. Its weapon was a long spear, so long that the points of the first five ranks all projected in front of the first rank. Pyrrhus selected his ground on the open plain. Seven times the Roman legions charged against his unbroken phalanxes. After the Roman attack was exhausted, Pyrrhus turned his elephants upon the Roman cavalry, which fled in confusion, followed by the rest of the Roman army. The Romans, though defeated in this battle, displayed wonderful courage and discipline, so that Pyrrhus exclaimed, “With such an army I could conquer the world!”

Battle of Beneventum and Departure of Pyrrhus (275 B.C.): Before abandoning Italy, Pyrrhus determined once more to try the fortunes of war. One of the consular armies, under Curius Dentatus, lay in a strong position near Beneventum in the hilly regions of Samnium. Pyrrhus resolved to attack this army before it could be reënforced. He stormed the Roman position, and was repulsed. The Roman consul then pursued him to the plains and gained a complete victory. Baffled and disappointed, Pyrrhus retreated to Tarentum; and leaving a garrison in that city under his lieutenant, Milo, he led the remnants of his army back to Greece. \~\

See Separate Article: ROMAN CONQUEST OF ITALY europe.factsanddetails.com

Hannibal’s Invades of Italy and Defeats the Romans in the Second Punic War

Hannibal finally reached the valley of the Po, with only twenty thousand foot and six thousand horse. Here he recruited his ranks from the Gauls, who eagerly joined his cause against the Romans. When the Romans were aware that Hannibal was really in Italy, they made preparations to meet and to destroy him. Sempronius was recalled with the army originally intended for Africa; and Scipio, who had returned from Massilia, gathered together the scattered forces in northern Italy and took up his station at Placentia on the Po. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Hannibal won three battles in Italy but lost the forth. Early Carthaginian victories left 15,000 Romans dead in one place and 20,000 in another. With their superior cavalry and what became textbook usage of bottlenecking tactics, Hannibal's forces defeated the Roman force of Flamininius in 217 B.C. at Lake Trasimene. Next he humiliated the Romans, by coldly coordinating his infantry and cavalry attacks, at Cannae in northern Italy, where 60,000 Romans were killed. This victory drew the north of Italy from Rome's sphere for some time.

These victories were followed by a massacre of 50,000 legionnaires (from an army of 75,000) at the Trebia River. Here the Roman were surrounded by flanking movements on both sides. Hannibal's genius killed 6000 legionnaires in minutes. After the stunning defeats, one Roman army was annihilated and Rome was nearly destroyed. The Romans were worried that Hannibal would take his revenge in most awful way. The statesmen Quintus Fabius Maximus was put in charge of the Roman army.

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLY CARTHAGE VICTORIES IN THE SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com

PUNIC WARS AND HANNIBAL africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): CARTHAGE SUCCESSES, ULTIMATE ROMAN VICTORY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HANNIBAL CROSSES THE ALPS: ELEPHANTS, POSSIBLE ROUTES AND HOW HE DID IT europe.factsanddetails.com

Battle of Cannae (216 B.C.)

At Cannae in northern Italy, Hannibal humiliated the Romans, by coldly coordinating his infantry and cavalry attacks, killing 60,000 Romans and drawing the north of Italy from Rome's sphere of influence for some time.

The cautious strategy of Fabius soon became unpopular; and the escape of Hannibal from Campania especially excited the dissatisfaction of the people. Two new consuls were therefore chosen, who were expected to pursue a more vigorous policy. These were Terentius Varro and Aemilius Paullus. Hannibal’s army was now in Apulia, near the little town of Cannae on the Aufidus River. To this place the consuls led their new forces, consisting of eighty thousand infantry and six thousand cavalry,—the largest army that the Romans had, up to that time, ever gathered on a single battlefield; Hannibal’s army consisted of forty thousand infantry and ten thousand cavalry. But the brain of Hannibal was more than a match for the forty thousand extra Romans, under the command of less able generals. The Roman consuls took command on alternate days. Paullus was cautious; but Varro was impetuous and determined to fight Hannibal at the first opportunity. As this was Hannibal’s greatest battle, we may learn something of his wonderful skill by looking at, its plan. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The Romans drew up their heavy infantry in solid columns, facing to the south, to attack the center of Hannibal’s line. In front of the heavy-armed troops were the light-armed soldiers, to act as skirmishers. On the Roman right, near the river, were two thousand of the Roman cavalry, and on the left wing were four thousand cavalry of the allies. With their army thus arranged, the Romans hoped to defeat Hannibal. But Hannibal laid his plan not simply to defeat the Roman army, but to draw it into such a position that it could be entirely destroyed. He therefore placed his weakest troops, the Spanish and Gallic infantry, in the center opposite the heavy infantry of the Romans, and pushed them forward in the form of a crescent, with the expectation that they would be driven back and pursued by the Romans. On either flank he placed an invincible body of African troops, his best and most trusted soldiers, drawn back in long, solid columns, so that they could fall upon the Romans when the center had been driven in. On his left wing, next to the river, were placed four thousand Spanish and Gallic cavalry, and on the right wing his superb body of six thousand Numidian cavalry, which was to swing around and attack the Roman army in the rear, when it had become engaged with the African troops upon the right and left. \~\

The description of this plan is almost a description of the battle itself. When the Romans had pressed back the weak center of Hannibal’s line, they found themselves ingulfed in the midst of the Carthaginian forces. Attacked on all sides, the Roman army became a confused mass of struggling men, and the battle became a butchery. The army was annihilated; seventy thousand Roman soldiers are said to have been slain, among whom were eighty senators and the consul Aemilius. The small remnant of survivors fled to the neighboring towns, and Varro, with seventy horsemen, took refuge in the city of Venusia. This was the most terrible day that Rome had seen since the destruction of the city by the Gauls, nearly two centuries before. Every house in Rome was in mourning. \~\

See Separate Article: BATTLE OF CANNAE: TACTICS, FIGHTING, IMPACT europe.factsanddetails.com

Hannibal ay Cannae

Battle of the Metaurus (207 B.C.)

Hasdrubal (Hannibal's brother) had been kept in Spain by the vigorous campaign which the Romans had conducted in that peninsula under the two Scipios. Upon the death of these generals, the young Publius Cornelius Scipio was sent to Spain and earned a great name by his victories. But Hasdrubal was determined to go to the rescue of his brother in Italy. He followed Hannibal’s path over the Alps into the valley of the Po. Hannibal had moved northward into Apulia, and was awaiting news from Hasdrubal. There were now two enemies in Italy, instead of one. One Roman army under Claudius Nero was, therefore, sent to oppose Hannibal in Apulia; and another army under Livius Salinator was sent to meet Hasdrubal, who had just crossed the river Metaurus, in Umbria. \~\

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “In 207 Hasdrubal finally managed to cross the Alps with 30,000 troops. The plan was for the brothers to link up in Apulia, but this design was thwarted by the bold action of the consul C. Claudius Nero. Nero left Hannibal unopposed in Apulia and raced north to intercept Hasdrubal, whom he met at the battle of the Metaurus River (207 B.C.). This time the Roman numerical advantage (both consular armies had combined for the occasion) was put to better use, and Nero was able to outflank Hasdrubal, who died on the field. Another attempt to reinforce Hannibal followed, with Mago landing at Genoa in Cisalpine Gaul; but he was turned back at Ariminium, and Hannibal simply hung on in the south, losing one town after another. Finally in 203, after 15 years on Italian soil, Hannibal returned to Africa to face the younger Scipio (later to be called Africanus). [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

It was necessary that Hasdrubal should be crushed before Hannibal was informed of his arrival in Italy. The consul Claudius Nero therefore left his main army in Apulia, and with eight thousand picked soldiers hurried to the aid of his colleague in Umbria. The battle which took place at the Metaurus was decisive; and really determined the issue of the second Punic war. The army of Hasdrubal was entirely destroyed, and he himself was slain. The first news which Hannibal received of this disaster was from the lifeless lips of his own brother, whose head was thrown by the Romans into the Carthaginian camp. Hannibal saw that the death of his brother was the doom of Carthage; and he sadly exclaimed, “O Carthage, I see thy fate!” Hannibal retired into Bruttium; and the Roman consuls received the first triumph that had been given since the beginning of this disastrous war. By 205 Scipio had subdued all of Spain, and returned to Rome in triumph to be elected consul. \~\

See Separate Article: SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): CARTHAGE SUCCESSES, ULTIMATE ROMAN VICTORY europe.factsanddetails.com

Battle of Zama

Battle of Zama

The Second Punic War ended when Hannibal was defeated by the Roman general Scipio who counterattacked in Northern Africa and routed the Carthaginian army at the Battle of Zama in 202 B.C. in Tunisia where the Romans employed a checkerboard formation to absorb an elephant charge and then counter-attacked. This was Hannibal's Waterloo.

At Zama, Hannibal fought at a great disadvantage. His own veterans were reduced greatly in number, and the new armies of Carthage could not be depended upon. Scipio changed the order of the legions, leaving spaces in his line, through which the elephants of Hannibal might pass without being opposed. In this battle Hannibal was defeated, and the Carthaginian army was annihilated. It is said that twenty thousand men were slain, and as many more taken prisoners.

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “For the battle at Zama there are two competing accounts, one reflected by both Appian and Dio Cassius, the other by Polybius (15. 9-14) and Livy (30. 32-35). As frequently, the latter is more coherent. Scipio thwarted the elephantine threat by leaving lanes in his ranks through which the beasts might pass, while Hannibal tried to guard against encirclement by keeping his best troops (the veterans from Italy) to the rear. According to Polybius many of the elephants panicked at the outset and charged back into Hannibal's lines; this probably has at least a grain of truth, but it also looks like the product of the popular superstition about Scipio' special favor in the eyes of the gods. The decisive move occurred late in the battle when the Numidian horse left off chasing the remnants of Hannibal's mounted troops (most of them also Numidians) and attacked his rear. After this decisive defeat on African soil Carthage was compelled to accept terms, which were substantially the same as the treaty of 204, except that now the indemnity was doubled to 10,000 talents (payable over 50 years), and the Carthaginians agreed not to wage war outside of Africa. Even within Africa they were to undertake campaigns only with the prior approval of the Senate and people of Rome. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“The lasting effect which Hannibal's sojourn in Italy had upon the collective memory of the Romans may be inferred from the prophetic words, woven by Virgil in the early years of Augustus' principate, which the angry Dido shouts as a curse at the fleeing Aeneas (Aeneid 4. 625-629):

May some avenger arise from my bones,

To harass the Dardan settlers with fire and sword,

Now or in future, whenever the resources are there;

I pray, may our shores oppose their shores, our waves

Their waves, our arms their arms. May future generations

carry on the fight. ^*^

See Separate Article: SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): CARTHAGE SUCCESSES, ULTIMATE ROMAN VICTORY europe.factsanddetails.com

Battle of Alesia: Caesar Victory Over Vercingetorix

In 52 B.C., he put down the last great Gallic-Celtic uprising. Vercingetorix, the leader of the Gallic-Celtic forces, surrendered himself at the feet of Caesar who sent him to Rome where the Gallic leader was imprisoned for six years and then paraded through the streets and strangled in the Forum.

Siege of Alesia

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “In 52 B.C. Caesar faced his most formidable Gallic opponent in Vercingetorix, a resourceful general whose initial successes induced almost all of the Gallic tribes to align themselves with him. The decisive victory came with the fall of the Gallic stronghold at Alesia (near modern Troyes; cf. Plut. Caes. 27) in 51, just in time to allow Caesar to turn his attentions to domestic affairs. By now the number of legions under Caesar's command had risen to 10, augmented by large contingents of Gallic auxiliaries (light-armed) and cavalry. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

With the defeat of Vercingetorix, the conquest of Gaul was then completed. A large part of the population had been either slain in war or reduced to slavery. The new territory was pacified by bestowing honors upon the Gallic chiefs, and self-government upon the surviving tribes. The Roman legions were distributed through the territory; but Caesar established no military colonies like those of Sulla. The Roman arts and manners were encouraged; and Gaul was brought within the pale of civilization. \~\

See Separate Article: JULIUS CAESAR'S MILITARY CAREER: SKILLS, LEADERSHIP, VICTORIES europe.factsanddetails.com

Caesar Defeats Pompey at the Battle of Pharsalus in Greece

In 48 B.C., Caesar pursued Pompey across the Adriatic and decisively defeats him at the Battle of Pharsalus in in southern Thessaly, in Greece. Although Pompey's army outnumbered Caesar's — when commanded about 20,000 men compared to 40,000 for Pompey — Caesar's army was more experienced. The senate pressured Pompey to attack first, Pompey reluctantly did so. After the loss, Pompey fled to Egypt where he was assassinated.

In the beginning of 48 B.C., with the few ships that he had collected, he transported his troops from Brundisium across the Adriatic to meet the army of Pompey. In the first conflict, at Dyrrachium, he was defeated. He then retreated across the peninsula in the direction of Pharsalus in order to draw Pompey away from his supplies on the seacoast. Suetonius wrote: Caesar blockaded Pompey for almost four months behind mighty ramparts, finally routed him”[Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Caesar receiving the head of Pompey

Plutarch wrote: “When the two armies were come into Pharsalia (Pharsalus), and both encamped there, Pompey’s thoughts ran the same way as they had done before, against fighting, and the more because of some unlucky presages, and a vision he had in a dream.† But those who were about him were so confident of success, that Domitius, and Spinther, and Scipio, as if they had already conquered, quarrelled which should succeed Cæsar in the pontificate. And many sent to Rome to take houses fit to accommodate consuls and prætors, as being sure of entering upon those offices, as soon as the battle was over. The cavalry especially were obstinate for fighting, being splendidly armed and bravely mounted, and valuing themselves upon the fine horses they kept, and upon their own handsome persons; as also upon the advantage of their numbers, for they were five thousand against one thousand of Cæsar’s. Nor were the numbers of the infantry less disproportionate, there being forty-five thousand of Pompey’s, against twenty-two thousand of the enemy. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

See Separate Article: CIVIL WAR AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON europe.factsanddetails.com

Battle of Philippi (42 B.C.): Defeat of Brutus and Cassius

The Triumvirate battled Cassius and Brutus, the murderers of Caesar, for control of Rome during a of civil war. In 42 B.C. Antony and Octavian defeated Brutus and Cassius, in two battles at Philippi in Macedonia; the credit went to Antony because Octavian was ill during the fighting. On the ostensibly Republican side, only Sextus Pompey survived with a fleet, and Domitius Ahenobarbus with the fleet of Brutus and Cassius. After the Battle of Phillipi Lepidus was stripped of his power and Octavian and Marc Antony divided the empire, with Octavian getting Italy and the west and Antony getting the east.

After Cicero and other enemies were murdered at home, the triumvirs set their sights on were now prepared to crush their enemies abroad. There were three of these enemies whom they were obliged to meet—Brutus and Cassius, who had united their forces in the East; and Sextus Pompeius, who had got possession of the island of Sicily, and had under his command a powerful fleet. While Lepidus remained at Rome, Antony and Octavian invaded Greece with an army of one hundred and twenty thousand men. Against them the two liberators, Brutus and Cassius, collected an army of eighty thousand men. The hostile forces met near Philippi (42 B.C.), a town in Macedonia on the northern coast of the Aegean Sea. Octavian was opposed to Brutus, and Antony to Cassius. Octavian was driven back by Brutus, while Antony, more fortunate, drove back the wing commanded by Cassius. As Cassius saw his flying legions, he thought that all was lost, and stabbed himself with the same dagger, it is said, with which he struck Caesar. This left Brutus in sole command of the opposing army; but he also was defeated in a second battle, and, following the example of Cassius, committed suicide. The double battle at Philippi decided the fate of the republic. As Cicero was its last political champion, Brutus and Cassius were its last military defenders; and with their death we may say that the republic was at an end. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

victorious Marc Antony

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “In Asia Brutus and Cassius had joined up, using the force of their erstwhile imperium to extort money from the provinces, and (after they were outlawed) declaring themselves a sort of government in exile (marked by their minting of coins). In 42 Antony and Octavian met Brutus and Cassius at Philippi in Macedonia; in the first battle, Antony defeated Cassius while Octavian's wing suffered at the hands of Brutus; but a few weeks later Brutus too was rolled up. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Antony was able to gather his strength, drawing support from former Caesarian governors in Gaul and Spain. He descended upon Decimus Brutus a second time and destroyed him without even having to fight a battle (Decimus' troops, like those of the western provincial armies, tended to be loyal to Caesar's name). The extent to which resistance to Octavian in the senate had collapsed may be gauged by the fact that now it was the turn of Brutus and Cassius to be outlawed (App. 3. 14. 95). This was Rome as the Republic crumbled: one month you were granted a major command, the next you were public enemy number one. Octavian's next move was to meet Antony and Lepidus. The idea that the three had already struck some sort of deal is belied by the fact that all brought their legions to the meeting, which took place on a small island, i.e. a place where an ambush was impossible. ^*^

See Separate Article: OCTAVIAN AND MARK ANTONY AFTER CAESAR’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024