CITIZENS IN ANCIENT ROME

military diploma that grants citizenshipRoman citizens generally could vote and had rights and responsibilities under a "well administered system of criminal and civil law.” Men of both the upper and lower classes could be citizens. Women were citizens but couldn’t vote or hold office and had few rights. Slaves were not allowed to be citizens. During the Roman Republic government officials were elected by Roman citizens. During the Roman Empire many local government officials were elected by Roman citizens but not the Emperor and high level officials.

Dr Valerie Hope of the Open University wrote for the BBC: “All free inhabitants were either citizens or non-citizens. Only citizens could hold positions in the administration of Rome and the other towns and cities of the empire, only citizens could serve in the legions, and only citizens enjoyed certain legal privileges. From the end of the first century B.C., Rome and the Roman empire were ruled by a succession of emperors. Political and military power was concentrated in their hands, and they represented the pinnacle of the imperial status hierarchy. Under the emperors the citizen vote in Rome was curtailed, but citizenship expanded rapidly across the empire, and was given as a reward to individuals, families and whole settlements. In A.D. 212 the emperor Caracalla expanded the franchise to all free inhabitants of the empire. [Source: Dr Valerie Hope, BBC, March 29, 2011]

Clelia Martínez Maza wrote in National Geographic History: Citizenship has its roots in Rome’s deep past. In the sixth century B.C., Rome passed from a monarchy to a republic with power residing in the Senate and the People of Rome. The acronym SPQR stands for Senatus populusque Romanus and can be seen emblazoned on many Roman structures built during the Republic as a sign of pride in the duties of civic life. Roman men had the right to vote and also bore serious responsibilities: They should be prepared to die, if necessary, in the service of Rome. This connection between rights and responsibilities created the concept of Roman citizenship, known in Latin as civitas, which would expand and change over the rise and fall of Rome. In practice, the plebeians (the general citizenry) had fewer voting rights than the aristocratic patricians. But the principle that a man of modest means could regard himself as much a Roman citizen as an aristocratic landowner was a powerful one. It helped forge a sense of unity and Roman identity[Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ROMAN REPUBLIC GOVERNMENT: HISTORY, CONCEPTS, INFLUENCES, STRENGTHS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN EMPIRE: SIZE, GOVERNMENT, ADMINISTRATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STRUCTURE OF THE ROMAN REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT: BRANCHES, CONSULS, SENATE, ASSEMBLIES, COMITIA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FALL OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC AND RISE OF IMPERIAL ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EVOLUTION OF ROMAN GOVERNMENT AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CICERO (105-43 B.C.): LIFE, CAREER, WRITINGS, LEGACY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POLITICS IN ANCIENT ROME: CAMPAIGNS, PATRONAGE, CORRUPTION AND ORATORY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PROPAGANDA IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Being a Roman Citizen” by Jane F. F. Gardner Amazon.com;

“The Politics of Munificence in the Roman Empire: Citizens, Elites and Benefactors in Asia Minor” by Arjan Zuiderhoek Amazon.com;

“Peasants, Citizens and Soldiers: Studies in the Demographic History of Roman Italy 225 BC–AD 100" by Luuk de Ligt (2012) Amazon.com;

“Rome's Last Citizen: The Life and Legacy of Cato, Mortal Enemy of Caesar”

by Rob Goodman, Jimmy Soni, (2014) Amazon.com;

“St. Paul the Traveler and Roman Citizen” by William M. Ramsay, Mark Wilson Amazon.com;

“On Government” (Penguin Classics) by Marcus Tullius Cicero, translated by Michael Grant (1994)

“Democracy: A Life” by Paul Cartledge (2016) Amazon.com;

“Citizenship in Classical Athens” by Josine Blok (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Constitution of the Roman Republic” by Andrew Lintott Amazon.com;

“The Twelve Tables” Amazon.com;

“Patricians and Plebeians: The Origin of the Roman State” by Richard E. Mitchell (1990) Amazon.com;

“The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic: The Thirty-five Urban and Rural Tribes”

by Lily Ross Taylor and Jerzy Linderski (2013) Amazon.com;

“On Obligations: De Officiis” (Oxford World's Classics) by Cicero Amazon.com

“Rome in the Late Republic” by Mary Beard and M Crawford (1999) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“The Government of the Roman Empire: A Sourcebook” (Routledge) by Barbara Levick Amazon.com;

“Imperial Institutions in Ancient Rome and Early China: A Comparative Analysis”

by Michael Loewe, Michael Nylan, T. Corey Brennan Amazon.com;

“Rome: An Empire's Story” by Greg Woolf (2012) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Experiencing Rome: Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire 1st Edition

by Janet Huskinson (1999) Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

Women and Types of Roman Citizens

There were different kinds of citizens, each with their own collection of rights and responsibilities. Dr Valerie Hope of the Open University wrote for the BBC: “Citizens could be divided into the privileged and the non-privileged — with some Roman citizens being very clearly distinguished by their power and privilege. These were the senators, equestrians and the provincial elite. The senate was the traditional ruling body of Rome, and under the emperors the senate continued to represent the citizen upper crust. The senate was usually limited to 600 members, and entrance was dependent on property qualifications and election to key offices. [Source: Dr Valerie Hope, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

“The equestrian order was traditionally limited to those who were entitled to a public horse. There were no limits to equestrian numbers, but property requirements had to be met. Senators were recognised by a toga with a broad purple stripe, while the equestrian wore a toga with a narrow purple stripe and a gold finger ring.” |::|

Clelia Martínez Maza wrote in National Geographic History: Roman citizenship was a complex concept that varied according to one’s gender, parentage, and social status. Full citizenship could only be claimed by males. A child born of a legitimate union between citizen father and mother would acquire citizenship at birth. In theory, freeborn Roman women were regarded as Roman citizens; in practice, however, they could not hold office or vote, activities considered key aspects of citizenship. [Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

A Roman woman, however, did not have her own potestas (legal power or agency); she was subject to the authority of her father and then of her husband. If she was left without father or husband, she would come under the power of a male guardian who would take control of her property and carry out certain legal transactions for her. This male guardian had to grant formal consent for her actions. Although they were excluded from public office and politics, freeborn Roman women could claim some benefits of being a citizen. Female citizens could own assets, dispose of them as they wished, participate in contracts and manage their properties with complete autonomy, unless these activities required legal action, in which case the guardian had to intervene.

See Separate Article: WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME: STATUS, INEQUALITY, LITERACY, RIGHTS europe.factsanddetails.com

How One Became a Roman Citizen

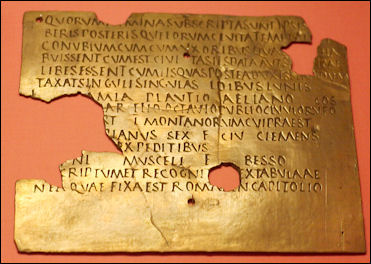

non-citizen Roman soldiers became citizens after their service was completed

Citizenship was generally passed down from father to son. The easiest way for non-citizens to become citizens was join the military. After being discharged for 20 years of service soldiers became citizens. The completion of military service provided citizenship not only to the soldier but to his entire family. Even barbarians were recruited with these promises.

Any male regarded as worthy, regardless of ethnic background, could become a Roman citizen. "E Pluibus Unum", the words featured on all American coins, meant that on any position in the empire was open to suitable candidates regardless of ethnic group or background. Within a fairly short time, the conquered people were made citizens of Rome and given all the rights and privileges that status entailed. Septimius Severus, a North African general became emperor of Rome and served for 18 years. Trajan, one of Rome's greatest emperors was from Spain.

When a foreigner received the right of citizenship, he took a new name, which was arranged on much the same principles as have been explained in the cases of freedmen. His original name was retained as a sort of cognomen, and before it were written the praenomen that suited his fancy and the nomen of the person, always a Roman citizen, to whom he owed his citizenship. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) ]

“The most familiar example is that of the Greek poet Archias, whom Cicero, in the well-known oration, defended; his name was Aulus Licinius Archias, He had long been attached to the family of the Luculli, and, when he was made a citizen, he took as his nomen that of his distinguished patron Lucius Licinius Lucullus; we do not know why he selected the praenomen Aulus. Another example is that of the Gaul mentioned by Caesar (B.G., I, 47), Gaïus Valerius Caburus. He took his name from Caius Valerius Flaccus, the governor of Gaul at the time that he received his citizenship. To this custom of taking the names of governors and generals is due the frequent occurrence of the name “Julius” in Gaul, “Pompeius” in Spain, and “Cornelius” in Sicily.”

From Soldier to Citizen in Ancient Rome

The military provided the main pathway for non-Romans to secure citizenship. Clelia Martínez Maza wrote in National Geographic History: As membership of the legion itself was reserved for citizens, a peregrinus (foreigner) could only be recruited into the auxiliary units. But on completing 25 years of service, he would be granted Roman citizenship as a reward when he graduated. He could then enjoy all the advantages of his new status, including conubium, the right to contract a legal marriage with a foreign woman. [Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

The peregrini could also obtain the right of citizenship by individual or collective concession, sometimes as a reward for exceptional military action. In 89 B.C., the commander-in-chief of the army, Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo (father of Pompey the Great), granted citizenship to a squadron of 30 Hispanic horsemen known as the turma Salluitana to reward their valor in helping to capture Asculum (modern Ascoli Piceno, Italy), a stronghold of the rebels during the Social War of the first-century B.C.

By dangling the promise of obtaining citizenship, Roman generals reinforced the loyalty of auxiliary troops in the provinces. Thus, a relationship—such as that between a patron and dependent—could be created between a general and his army. Being able to call on these loyal troops proved an invaluable resource during civil wars. When Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius and Pompey joined forces to fight the threat of Quintus Sertorius in Hispania (Spain) from 75 B.C., both generals granted citizenship to peregrini there who were loyal to their cause. On gaining citizenship, many soldiers often named themselves for the generals who had granted it. A number of inscriptions have been found in Spain bearing the names Caecilius and Pompey.

Among those granted citizenship by Pompey was one Lucius Cornelius Balbus, member of a powerful merchant family of Punic origin who settled in Gades (modern Cadiz in southern Spain). Balbus’s enemies accused him of usurping Roman citizenship and in 55 B.C. he was put on trial. Cicero acted as his defence and Balbus was acquitted. Balbus became consul of Rome in 40 B.C. and eventually a confidante of Julius Caesar, to the point that he managed Caesar’s private fortune.

Privileges and Responsibilities of Roman Citizens

patricians

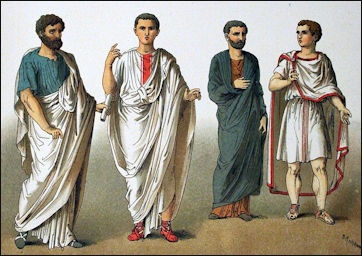

Clelia Martínez Maza wrote in National Geographic History: The privileges enjoyed by full citizens were wide-ranging: They could vote in assemblies and elections; own property; get married legally; have their children inherit property; stand for election and access public office; participate in priesthoods; and enlist in the legion. Male citizens could also engage in commercial activity in Roman territory. [Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

Every citizen between the ages of seventeen and forty-five was obliged to serve in the army, when the public service required it. In early times the wars lasted only for a short period, and consisted in ravaging the fields of the enemy; and the soldier’s reward was the booty which he was able to capture. But after the siege of Veii, the term of service became longer, and it became necessary to give to the soldiers regular pay. This pay, with the prospect of plunder and of a share in the allotment of conquered land; furnished a strong motive to render faithful service. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

In return for such rights, citizens were obliged to contribute to military expenditure in proportion to their wealth. By law they had to register in the census so that the state could calculate which social class they belonged to based on their wealth.

Only citizens had the right to wear the toga, the quintessential Roman garment that was placed over the tunic and covered a man's body and shoulders. The toga was time-consuming to put on, and left one arm immobilized under its complex folds. Restrictive and impractical, it had become unpopular as everyday clothing by the late republic. As the only outward sign of Roman citizenship, it still played a powerful ceremonial and ritual role. After puberty, boys swapped the purple trimmed toga praetexta for the plain toga virilis of a man.

Plebeians, Patricians and Evolution of Roman Citizenship

The idea of citizenship first evolved in ancient Greece. Roman mythology claims that the Roman idea of citizenship was created by it legendary rulers but more likely the idea was imported at least in part from the Greeks. The Athenians had a form of citizenry that excluded a lot of people but did grant certain rights those who possessed citizenship. In the early days of Rome, patricians were the ruling class. Only certain families were members of the patrician class and members had to be born patricians. The patricians were a very small percentage of the Roman population, but they held all the power. All the other people were Plebeians.

Over time the separation between the patricians and the plebeians was gradually broken down, with old patrician aristocracy passing away, and Rome becoming in theory, a democratic republic. Everyone who was enrolled in the thirty-five tribes was a full Roman citizen, and had a share in the government. But we must remember that not all the persons who were under the Roman authority were full Roman citizens. The inhabitants of the Latin colonies were not full Roman citizens. They could not hold office, and only under certain conditions could they vote. The Italian allies were not citizens at all, and could neither vote nor hold office. And now the conquests had added millions of people to those who were not citizens. The Roman world was, in fact, governed by the comparatively few people who lived in and about the city of Rome. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

“But even within this class of citizens at Rome, there had gradually grown up a smaller body of persons, who became the real holders of political power. Later, this small body formed a new nobility—the optimates. All who had held the office of consul, praetor, or curule aedile—that is, a “curule office”—were regarded as nobles (nobiles), and their families were distinguished by the right of setting up the ancestral images in their homes (ius imaginis). Any citizen might, it is true, be elected to the curule offices; but the noble families were able, by their wealth, to influence the elections, so as practically to retain these offices in their own hands. \~\

Eventually the plebeians were allowed to elect their own government officials. They elected "tribunes" who represented the plebeians and fought for their rights. They had the power to veto new laws from the Roman senate. As time went on, the legal differences between the plebeians and the patricians diminished. The plebeians could be elected to the senate and even be consuls. Plebeians and patricians could also get married. Wealthy plebeians became part of the Roman nobility. However, despite changes in the laws, the patricians always held a majority of the wealth and power in Ancient Rome. [Source: Ducksters ^^]

The three citizen assemblies of the Roman Republic (not including the Senate): 1) All 3 assemblies included the entire electorate, but each had a different internal organization (and therefore differences in the weight of an individual citizen's vote). 2) All 3 assemblies made up of voting units; the single vote of each voting unit determined by a majority of the voters in that unit; measures passed by a simple majority of the units. 3) They were -called comitia. specifically the comitia curiata, comitia centuriata, and comitia plebis tributa (also the concilium plebis or comitia populi tributa). [Source: University of Texas at Austin ==]

See Separate Article: PLEBEIANS AND PATRICIANS IN THE EARLY ROMAN REPUBLIC europe.factsanddetails.com

Roman Citizenship Given to Conquered Territories

Through military expansion, colonization, and the granting of citizenship to conquered tribesmen, Rome annexed all the territory south of the Po in present-day Italy during a hundred period before 268 B.C.. Latin and Italic tribes were absorbed first, followed by Etruscans and the Greek colonies in south. Clelia Martínez Maza wrote in National Geographic History: As Rome began to expand in Italy, it faced the question of whether or not to grant this coveted civitas status to the non-Roman communities it was conquering. Such a gesture might have helped consolidate loyalty in certain circumstances, but it also removed an ethnic dimension from citizenship, an idea that unsettled many Romans. An early example of the expansion of civitas to non-Roman peoples took place in the fourth century B.C., when Rome had granted a diluted form of citizenship to the Etruscan city of Caere, around 35 miles from Rome. As the conquest of Italy continued, Rome gave its newly subdued peoples a similar package of diluted rights, which often excluded the right to vote. [Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

The colonies of citizens sent out by Rome were allowed to retain all their rights of citizenship, being permitted even to come to Rome at any time to vote and help make the laws. These colonies of Roman citizens thus formed a part of the sovereign state; and their territory, wherever it might be situated, was regarded as a part of the ager Romanus. Such were the colonies along the seacoast, the most important of which were situated on the shores of Latium and of adjoining lands. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

After the great Latin war (340-338 B.C.), it was evident that newly conquered people should be granted rights but that all the cities and towns were not equally fit to exercise the right of Roman citizenship; and upon this was based the distinction between perfect and imperfect citizenship. The subject towns of Latium and those of Campania were thus treated in various ways.

Towns fully Incorporated: In the first place, many of the towns of Latium were fully adopted into the Roman state. Their inhabitants became full Roman citizens, with all the private and public rights, comprising the right to trade and intermarry with Romans, the right to vote in the assemblies at Rome, and the right to hold any public office. Their lands became a part of the Roman domain. The new territory was organized into two new tribes, making now the total number twenty-nine. \~\

Towns partly Incorporated: But most of the towns of Latium. received only a part of the rights of citizenship. To their inhabitants were given the right to trade and the right to intermarry with Roman citizens, but not the right to vote or to hold office. This imperfect, or qualified, citizenship (which had before been given to the town of Caere) now became known as the “Latin right.”

Social Wars (91-88 B.C.): A Struggle to Obtain Citizenship

Resentment grew among the conquered peoples. Many felt they were shouldering responsibilities, such as military service, without receiving their fair share of privileges. In the 1st century B.C. began, some of Rome’s Italian allies began clamoring for more rights, and threatening war if their demands were not granted. We remember that when Rome had conquered Italy, she did not give the Italian people the rights of citizenship. They were made subject allies, but received no share in the government. The Italian allies had furnished soldiers for the Roman armies, and had helped to make Rome the mistress of the Mediterranean. They believed, therefore, that they were entitled to all the rights of Roman citizens; and some of the patriotic leaders of Rome believed so too. But it seemed as difficult to break down the distinction between Romans and Italians as it had been many years before to remove the barriers between the patricians and the plebeians. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

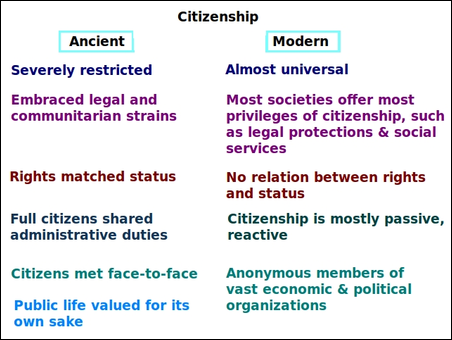

ancient citizenship versus modern citizenship

The situation came to a head with the Social War of the first-century B.C., a series of revolts against Roman rule in central Italy. The death of Marcus Livius Drusus (before 122 BC – 91 B.C.), a Roman politician and reformer drove the Italians to revolt. The “social war,” or the war of the allies (socii). It was, in fact, a war of secession. The purpose of the allies was now, not to obtain the Roman franchise, but to create a new Italian nation, where all might be equal. They accordingly organized a new republic with the central government at Corfinium, a town in the Apennines. The new state was modeled after the government at Rome, with a senate of five hundred members, two consuls, and other magistrates. Nearly all the peoples of central and southern Italy joined in this revolt. Rome was now threatened with destruction, not by a foreign enemy like the Cimbri and Teutones, but by her own subjects. The spirit of patriotism revived; and the parties ceased for a brief time from their quarrels. Even Marius returned to serve as a legate in the Roman army. A hundred thousand men took the field against an equal number raised by the allies. In the first year the war was unfavorable to Rome. \~\

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “As far as the common people were concerned, even with citizenship they would have little chance to vote (as no votes could be cast en absentia, but physical presence in Rome was required) and even less to join the ruling class. The local aristocracy, on the other hand, could easily cope with the journey to the city, and might also hope for a share of the real pie, membership in the Senate and the chance to climb the cursus honorum. It is tempting to think that the impetus for the Social War came from the local aristocracies rather than from the rank and file. In any case the Social War was a conflict on a grand scale, with 100,000 men in arms against Rome. Its object was not to obliterate Rome but to reinvent the political landscape of Italy, to form a new state called Italia in which the position of Rome would be as equal of other large cities. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

In order to quell the revolt, laws were passed to grant citizenship to all those who opposed the revolt, or to rebels who were willing to lay down arms. The concession embodied in the Lex Iulia, propogated by the consul of 90 BC, L. Iulius Caesar. The law offered the desired citizenship to all Italians (except the inhabitants of Cisalpine Gaul) who ceased hostilities immediately; possibly a separate law also allowed those individuals whose cities remained at war with Rome to gain citizenship on a separate basis ( Lex Papiria-Plautia ). The question is why any of the Italians would have continued to fight after the passage of the Lex Iulia. Possible answers: (a) the law merely restored the status quo ante bellum, whereas the objective of a new nation of Italia without Rome at its head was not met, or (b) the law stipulated that the new citizens could be enrolled only in two (or eight or ten) newly created tribes, which would limit the extent to which the weight of their numbers would be felt in the voting. If (b) is correct, as Salmon believes following Appian BC 1.49, then dissatisfaction over the half-measure explains the continuation of the fighting after its passage.” ^*^

The gesture was regarded as a success: The revolt was successfully terminated soon after. Although Rome was victorious in the field, the Italians obtained what they had demanded before the war began, that is, the rights of Roman citizenship. The Romans granted the franchise (1) to all Latins and Italians who had remained loyal during the war (lex Iulia, B.C. 90); and (2) to every Italian who should be enrolled by the praetor within sixty days of the passage of the law (lex Plautia Papiria, B.C. 89). Every person to whom these provisions applied was now a Roman citizen. The policy of incorporation, which had been discontinued for so long a time, was thus revived. The distinction between Romans, Latins, and Italians was now broken down, at least so far as the Italian peninsula was concerned. The greater part of Italy was joined to the ager Romanus, and Italy and Rome became practically one nation. \~\

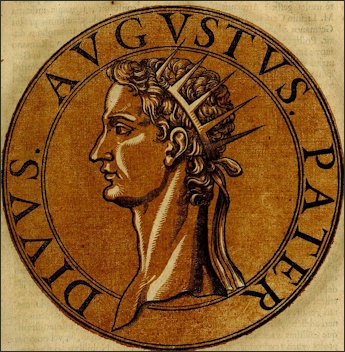

Expansion of Roman Citizenship Under Caesar, Augustus and Other Emperors

Clelia Martínez Maza wrote in National Geographic History: During the rule of Julius Caesar in the first century B.C., a law was passed granting Roman citizenship to colonies and municipia in Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy), the first time this right had been expanded beyond Roman Italy. This qualified form of citizenship was known as Jus Latii, often referred to in English as Latin rights. It gave holders the right to enter into Roman legal contracts and the right to legal intermarriage. [Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

Under Augustus (ruled 27 B.C. - B.C. 14) the rights of citizenship was granted to a large number of people that had previously been excluded. At the beginning of this period only the inhabitants of a comparatively small part of the Italian peninsula were citizens of Rome. The franchise was restricted chiefly to those who dwelt upon the lands in the vicinity of the capital. But during the civil wars the rights of citizenship had been extended to all parts of Italy and to many cities in Gaul and Spain.

Part of the Res Gestae — a list of Augustus’s accomplishments likely penned by Augustus himself — reads: “I undertook civil and foreign wars both by land and by sea; as victor therein I showed mercy to all surviving [Roman] citizens. Foreign nations, that I could safely pardon, I preferred to spare rather than to destroy. About 500,000 Roman citizens took the military oath of allegiance to me. Rather over 300,000 of these have I settled in colonies, or sent back to their home towns (municipia) when their term of service ran out; and to all of these I have given lands bought by me, or the money for farms — and this out of my private means. I have taken 600 ships, besides those smaller than triremes.

In A.D. 74, Emperor Vespasian further expanded Latin rights to Hispania. Communities in modern-day Spain and Portugal were granted qualified citizenship in the form of Latin rights, the same status that had been extended to Italian settlements during the period of Julius Caesar the century before. The edict was another major step forward in the continuing Romanization of an empire about to reach its maximum bounds. Subsequent emperors continued this process, little by little bestowing citizenship across the Roman world. In imperial times, any Roman citizen from any part of the Empire facing trial could express their desire to appeal directly to Caesar.

Claudius Admits Provincials to the Senate

The process of giving more rights to more people was continued by Claudius I (ruled A.D. 41- 54). He made Thrace, Lycia in Asia Minor and Mauretania in Africa provinces and gave the right of citizenship to residents of the provinces. The civitas was granted to a large part of Gaul, thus carrying out the policy which had been begun by Julius Caesar. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Claudius being proclaimed emperor by his soldiers

In a speech on admitting provincials to the Senate by Claudius (41–54 A.D.), Tacitus (b.56/57-after 117 A.D.) wrote in “Annals” (A.D. 48): “In the consulship of Aulus Vitellius and Lucius Vipstanus the question of filling up the Senate was discussed, and the chief men of Gallia Comata, as it was called, who had long possessed the rights of allies and of Roman citizens, sought the privilege of obtaining public offices at Rome. There was much talk of every kind on the subject, and it was argued before the emperor with vehement opposition. "Italy," it was asserted, "is not so feeble as to be unable to furnish its own capital with a senate. Once our native-born citizens sufficed for peoples of our own kin, and we are by no means dissatisfied with the Rome of the past. To this day we cite examples, which under our old customs the Roman character exhibited as to valour and renown. Is it a small thing that Veneti and Insubres have already burst into the Senate-house, unless a mob of foreigners, a troop of captives, so to say, is now forced upon us? What distinctions will be left for the remnants of our noble houses, or for any impoverished senators from Latium? Every place will be crowded with these millionaires, whose ancestors of the second and third generations at the head of hostile tribes destroyed our armies with fire and sword, and actually besieged the divine Julius at Alesia. These are recent memories. What if there were to rise up the remembrance of those who fell in Rome's citadel and at her altar by the hands of these same barbarians! Let them enjoy indeed the title of citizens, but let them not vulgarise the distinctions of the Senate and the honours of office." [Source: Tacitus, The Annales 11.23-25]

“These and like arguments failed to impress the emperor. He at once addressed himself to answer them, and thus harangued the assembled Senate. "My ancestors, the most ancient of whom was made at once a citizen and a noble of Rome, encourage me to govern by the same policy of transferring to this city all conspicuous merit, wherever found. And indeed I know, as facts, that the Julii came from Alba, the Coruncanii from Camerium, the Porcii from Tusculum, and not to inquire too minutely into the past, that new members have been brought into the Senate from Etruria and Lucania and the whole of Italy, that Italy itself was at last extended to the Alps, to the end that not only single persons but entire countries and tribes might be united under our name. We had unshaken peace at home; we prospered in all our foreign relations, in the days when Italy beyond the Po was admitted to share our citizenship, and when, enrolling in our ranks the most vigorous of the provincials, under colour of settling our legions throughout the world, we recruited our exhausted empire. Are we sorry that the Balbi came to us from Spain, and other men not less illustrious from Narbon Gaul? Their descendants are still among us, and do not yield to us in patriotism.

"What was the ruin of Sparta and Athens, but this, that mighty as they were in war, they spurned from them as aliens those whom they had conquered? Our founder Romulus, on the other hand, was so wise that he fought as enemies and then hailed as fellow-citizens several nations on the very same day. Strangers have reigned over us. That freedmen's sons should be intrusted with public offices is not, as many wrongly think, a sudden innovation, but was a common practice in the old commonwealth. But, it will be said, we have fought with the Senones. I suppose then that the Volsci and Aequi never stood in array against us. Our city was taken by the Gauls. Well, we also gave hostages to the Etruscans, and passed under the yoke of the Samnites. On the whole, if you review all our wars, never has one been finished in a shorter time than that with the Gauls. Thenceforth they have preserved an unbroken and loyal peace. United as they now are with us by manners, education, and intermarriage, let them bring us their gold and their wealth rather than enjoy it in isolation. Everything, Senators, which we now hold to be of the highest antiquity, was once new. Plebeian magistrates came after patrician; Latin magistrates after plebeian; magistrates of other Italian peoples after Latin. This practice too will establish itself, and what we are this day justifying by precedents, will be itself a precedent."

“The emperor's speech was followed by a decree of the Senate, and the Aedui were the first to obtain the right of becoming senators at Rome. This compliment was paid to their ancient alliance, and to the fact that they alone of the Gauls cling to the name of brothers of the Roman people.”

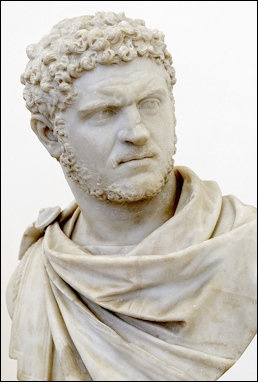

Edict of Caraculla: Granting Citizenship to All Members of the Roman Empire

Caracalla

The Afro-Syrian warrior Marcus Aurelius Antoninus served as Emperor under the nickname Caracalla (ruled A.D. 198 - 217). He left behind a "trail or massacre and murder" and made some noteworthy reforms, namely granting citizenship to all free (non-slave) members of the empire's population. He did this mainly to generate income. By requiring all these new citizens to pay taxes, he was able to strengthen the army's financial base.

Caraculla got rid of all distinctions between Italians and provincials with the Constitutio Antoniniana in 212 A.D., which extended Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. The Edict of Caracalla (officially the Constitutio Antoniniana (Latin: "Constitution [or Edict] of Antoninus")) declared that all free men in the Roman Empire were to be given full Roman citizenship and all free women in the Empire were given the same rights as Roman women. Before 212, for the most part only inhabitants of Italia held full Roman citizenship. Colonies of Romans established in other provinces, Romans (or their descendants) living in provinces, the inhabitants of various cities throughout the Empire, and a few local nobles (such as kings of client countries) also held full citizenship. Provincials, on the other hand, were usually non-citizens, although some held the Latin Right. However, by the previous century Roman citizenship had already lost much of its exclusiveness and become more available. [Source: Wikipedia]

With the Edict of Caracalla the Roman franchise, which had been gradually extended by the previous emperors, was now conferred to all the free inhabitants of the Roman world. The edict was issued primarily to increase tax revenue. Even so, the edict was in the line of earlier reforms and effaced the last distinction between Romans and provincials. The conciliatory policy toward the tribal people (“barbarians”) was adopted, by granting to them peaceful settlements in the frontier provinces. Not only the Roman territory, but the army and the offices of the state, military and civil, were gradually opened to Germans and other tribe members who were willing to become Roman subjects.

The Edict of Caracalla was the final step toward extending Roman citizenship to nearly all the subject peoples of the empire. Although Caracalla was a spendthrift and unstable ruler, and extending citizenship mainly as a quick way to increase his tax base, the idea that people from different ethnic backgrounds can share the same rights, responsibilities, and sense of national pride was quite significant. The century before Caracalla’s edict, the orator Aelius Aristides said: “And neither does the sea nor a great expanse of intervening land keep one from being a citizen; nor here are Asia and Europe distinguished. But all lies open to all men. No one is a foreigner. . . and just as the earth’s ground support all men, so Rome too receives men from every land.” [Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

St. Paul — Christianized Jew and Roman Citizen

One of the most famous examples of a citizen invoking his rights as a Roman citizen is the apostle Paul. Born a Jew in 4 B.C. in Tarsus in modern-day Turkey, Paul was a Roman citizen. Following his arrest by the Romans in A.D. 59, Paul used his status to dramatically halt his trial before Porcius Festus, the governor of Judaea: “Festus, when he had conferred with the council, answered, ‘You have appealed to Caesar? To Caesar you shall go!’“ (Acts: 25:12). Paul was transferred to Rome, where he stayed for several years before is believed to be have been killed there. [Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

Conversion of Paul

Dr Neil Faulkner wrote for the BBC: The Roman Empire "was controlled through a network of several thousand provincial towns. Each town dominated the countryside around it and functioned as a centre of local government. The country gentry were organised into a class of town councillors or 'decurions'. Most continued to draw most of their income from estates, but they took up urban residence, joined the political fray, contributed to the cost of public buildings, and became patrons of the arts. |::| [Source: Dr Neil Faulkner, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“St Paul probably belonged to this group (he is described to us as a 'tent-maker', but this may well mean a merchant who owned workshops, perhaps even a contractor supplying the army). We know that he was born a Roman citizen. It was this that saved him from trial in a hostile local court, since Roman citizens were entitled to demand the emperor's justice - which is why, after his arrest in 58 AD, he was dispatched to Rome. |::|

“His case shows that in the early first century A.D. a well-to-do Jew from Tarsus in Southern Turkey could be a Roman. Paul's case illustrates one of the advantages of Roman citizenship - legal protection. But there were many others. Roman society was meshed together by networks of patronage. Citizenship gave one access to the most important of these networks and the opportunities for economic, social and political advancement they offered. Consequently, most men of rank within the empire were eager to become Roman citizens - and the Romanisation we see represented by archaeological discoveries is evidence of both their striving and their success.” |::|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024