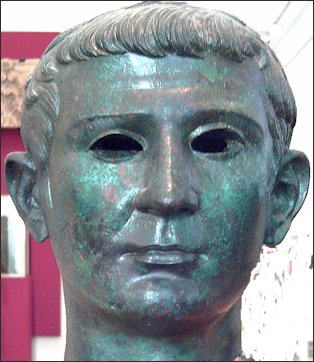

CRUELTY OF TIBERIUS (A.D. 14-37)

Tiberus (ruled from A.D. 14-37), Augustus’s successor, was known for hedonism, decadence and cruelty. The adopted stepson of Augustus, he reportedly had a servant named "Sphincter;" tossed lovers that displeased him off a 1,000-foot cliff at Capri — the island near present-day Naples — and changed laws on execution of virgins that decreed that condemned virgins should be deflowered by their executioners before their sentence was carried out. According to Tacitus and Suetonius, Tiberus was once presented a fish from a local fisherman, who was then promptly beaten with the fish. Afterwards the fisherman commented he was glad he didn't give the large crab he caught to the emperor. Tiberus overheard this and ordered the man to be beaten with the crab. Tiberus spent his last years in a palace on Capri.

Suetonius wrote: “His cruel and cold-blooded character was not completely hidden even in his boyhood. His teacher of rhetoric, Theodorus of Gadara, seems first to have had the insight to detect it, and to have characterized it very aptly, since in taking him to task he would now and then call him "mud kneaded with blood." But it grew still more noticeable after he became emperor, even at the beginning, when he was still courting popularity by a show of moderation. When a funeral was passing by and a jester called aloud to the corpse to let Augustus know that the legacies which he had left to the people were not yet being paid, Tiberius had the man haled before him, ordered that he be given his due and put to death, and bade him go tell the truth to his father. Shortly afterwards, when a Roman knight called Pompeius stoutly opposed some action in the Senate, Tiberius threatened him with imprisonment, declaring that from a Pompeius he would make of him a Pompeian, punning cruelly on the man's name and the fate of the old party. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) Tiberius, “De Vita Caesarum,” written A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920), pp. 291-401]

“A few days after he reached Capreae and was by himself, a fisherman appeared unexpectedly and offered him a huge mullet; whereupon in his alarm that the man had clambered up to him from the back of the island over rough and pathless rocks, he had the poor fellow's face scrubbed with the fish. And because in the midst of his torture the man thanked his stars that he had not given the emperor an enormous crab that he had caught, Tiberius had his face torn with the crab also. He punished a soldier of the praetorian guard with death for having stolen a peacock from his preserves. When the litter in which he was making a trip was stopped by brambles, he had the man who went ahead to clear the way, a centurion of the first cohorts, stretched out on the ground and flogged half to death.

“Not a day passed without an execution, not even those that were sacred and holy; for he put some to death even on New Year's day. Many were accused and condemned with their children and even by their children. The relatives of the victims were forbidden to mourn for them. Special rewards were voted the accusers and sometimes even the witnesses. The word of no informer was doubted. Every crime was treated as capital, even the utterance of a few simple words. A poet was charged with having slandered Agamemnon in a tragedy, and a writer of history of having called Brutus and Cassius the last of the Romans. The writers were at once put to death and their works destroyed, although they had been read with approval in public some years before in the presence of Augustus himself. Some of those who were consigned to prison were denied not only the consolation of reading, but even the privilege of conversing and talking together. Of those who were cited to plead their causes some opened their veins at home, feeling sure of being condemned and wishing to avoid annoyance and humiliation, while others drank poison in full view of the Senate; yet the wounds of the former were bandaged and they were hurried half-dead, but still quivering, to the prison.

“Every one of those who were executed was thrown out upon the Stairs of Mourning and dragged to the Tiber with hooks, as many as twenty being so treated in a single day, including women and children. Since ancient usage made it impious to strangle maidens, young girls were first violated by the executioner and then strangled. Those who wished to die were forced to live; for he thought death so light a punishment that when he heard that one of the accused, Carnulus by name, had anticipated his execution, he cried: "Carnulus has given me the slip"; and when he was inspecting the prisons and a man begged for a speedy death, he replied: "I have not yet become your friend." An ex-consul has recorded in his Annals that once at a large dinner-party, at which the writer himself was present, Tiberius was suddenly asked in a loud voice by one of the dwarfs that stood beside the table among the jesters why Paconius, who was charged with treason, remained so long alive; that the emperor at the time chided him for his saucy tongue, but a few days later wrote to the Senate to decide as soon as possible about the execution of Paconius.

“He increased his cruelty and carried it to greater lengths, exasperated by what he learned about the death of his son Drusus. At first supposing that he had died of disease, due to his bad habits, on finally learning that he had been poisoned by the treachery of his wife Livilla and Sejanus, there was no one whom Tiberius spared from torment and death. Indeed, he gave himself up so utterly for whole days to this investigation and was so wrapped up in it, that when he was told of the arrival of a host of his from Rhodes,whom he had invited to Rome in a friendly letter, he had him put to the torture at once, supposing that someone had come whose testimony was important for the case. On discovering his mistake, he even had the man put to death, to keep him from giving publicity to the wrong done him. At Capreae they still point out the scene of his executions, from which he used to order that those who had been condemned after long and exquisite tortures be cast headlong into the sea before his eyes, while a band of marines waited below for the bodies and broke their bones with boathooks and oars, to prevent any breath of life from remaining in them. Among various forms of torture he had devised this one: he would trick men into loading themselves with copious draughts of wine, and then on a sudden tying up their private parts, would torment them at the same time by the torture of the cords and of the stoppage of their water. And had not death prevented him, and Thrasyllus, purposely it is said, induced him to put off some things through hope of a longer life, it is believed that still more would have perished, and that he would not even have spared the rest of his grandsons; for he had his suspicions of Gaius and detested Tiberius as the fruit of adultery. And this is highly probable, for he used at times to call Priam happy, because he had outlived all his kindred.

Categories with related articles in this website: Early Ancient Roman History (34 articles) factsanddetails.com; Later Ancient Roman History (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Life (39 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Art and Culture (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Government, Military, Infrastructure and Economics (42 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ;

“Outlines of Roman History” forumromanum.org; “The Private Life of the Romans” forumromanum.org|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu;

Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org

The Roman Empire in the 1st Century pbs.org/empires/romans;

The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ;

Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors roman-emperors.org;

British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;

Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art;

The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ;

Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu;

Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ;

History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame /web.archive.org ;

United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Caligula (ruled from A.D. 37-41)

Caligula

Caligula (born A.D. 12, ruled A.D. 37-41) had a great passion for women, gladiator games, chariot racing, theatrical performances, ships and violence. He liked to watch people being tortured and executed and murdered his brother along with countless others. He lasted only four years in power before he was assassinated. Some scholars dismiss accounts of Caligula's excesses as exaggerated by historians and a public that didn't like him. Other than the great ship he built there is no archaeological evidence that he spent more or was more wasteful than other emperors.

On his early life, Suetonius wrote: “Even at that time he could not control his natural cruelty and viciousness, but he was a most eager witness of the tortures and executions of those who suffered punishment, revelling at night in gluttony and adultery, disguised in a wig and a long robe, passionately devoted besides to the theatrical arts of dancing and singing, in which Tiberius very willingly indulged him,in the hope that through these his savage nature might be softened. This last was so clearly evident to the shrewd old man, that he used to say now and then that to allow Gaius to live would prove the ruin of himself and of all men, and that he was rearing a viper for the Roman people and a Phaethon for the world.”

Caligula's Sadism and Cruelty

Caligula brutally murder people for fun and used the law as an instrument of torture. Patrick Ryan wrote in Listverse: “. He believed prisoners should feel a painful death. He would kill his opponents slowly and painfully over hours or days. He decapitated and strangled children. People were beaten with heavy chains. He forced families to attend their children’s execution. Many people had their tongues cut off. He fed prisoners to a lions, panthers and bears and often killed gladiators. One gladiator alone was beaten up for two days full days. He sometimes ordered people to be killed by elephants. He caused many to die of starvation. Sawing people was one of his favorite things to do, which filleted the spine and spinal cord from crotch down to the chest. He liked to chew up the testicles of victims. One time Caligula said “I wish Rome had but one neck, so that I could cut off all their heads with one blow!”“ [Source: Patrick Ryan, Listverse, May 30, 2012]

Suetonius wrote: “ Being disturbed by the noise made by those who came in the middle of the night to secure the free seats in the Circus, he drove them all out with cudgels; in the confusion more than twenty Roman equites were crushed to death, with as many matrons and a countless number of others. At the plays in the theater, sowing discord between the people and the equites, he scattered the gift tickets ahead of time, to induce the rabble to take the seats reserved for the equestrian order. At a gladiatorial show he would sometimes draw back the awnings when the sun was hottest and give orders that no one be allowed to leave; then removing the usual equipment, he would match worthless and decrepit gladiators against mangy wild beasts, and have sham fights between householders who were of good repute, but conspicuous for some bodily infirmity. Sometimes too he would shut up the granaries and condemn the people to hunger...An ex-praetor who had retired to Anticyra for his health, sent frequent requests for an extension of his leave, but Caligula had him put to death, adding that a man who had not been helped by so long a course of hellebore needed to be bled. On signing the list of prisoners who were to be put to death later, he said that he was clearing his accounts. Having condemned several Gauls and Greeks to death in a body, he boasted that he had subdued Gallograecia. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

Caligula in action

“The following are special instances of his innate brutality. When cattle to feed the wild beasts which he had provided for a gladiatorial show were rather costly, he selected criminals to be devoured, and reviewing the line of prisoners without examining the charges, but merely taking his place in the middle of a colonnade, he bade them be led away "from baldhead to baldhead." A man who had made a vow to fight in the arena if the emperor recovered, he compelled to keep his word, watched him as he fought sword in hand, and would not let him go until he was victorious, and then only after many entreaties. Another who had offered his life for the same reason, but delayed to kill himself, he turned over to his slaves, with orders to drive him through the streets decked with sacred boughs and fillets, calling for the fulfilment of his vow, and finally hurl him from the embankment.

“Many men of honorable rank were first disfigured with the marks of branding-irons and then condemned to the mines, to work at building roads, or to be thrown to the wild beasts; or else he shut them up in cages on all fours, like animals, or had them sawn asunder. Not all these punishments were for serious offences, but merely for criticizing one of his shows, or for never having sworn by his Genius. He forced parents to attend the executions of their sons, sending a litter for one man who pleaded ill health, and inviting another to dinner immediately after witnessing the death, and trying to rouse him to gaiety and jesting by a great show of affability. He had the manager of his gladiatorial shows and beast-baitings beaten with chains in his presence for several successive days, and would not kill him until he was disgusted at the stench of his putrefied brain. He burned a writer of Atellan farces alive in the middle of the arena of the amphitheatre, because of a humorous line of double meaning. When a Roman eques on being thrown to the wild beasts loudly protested his innocence, he took him out, cut off his tongue, and put him back again.

“Having asked a man who had been recalled from an exile of long standing, how in the world he spent his time there, the man replied by way of flattery: "I constantly prayed the gods for what has come to pass, that Tiberius might die and you become emperor." Thereupon Caligula, thinking that his exiles were likewise praying for his death, sent emissaries from island to island to butcher them all. Wishing to have one of the senators torn to pieces, he induced some of the members to assail him suddenly, on his entrance into the Senate, with the charge of being a public enemy, to stab him with their styluses, and turn him over to the rest to be mangled; and his cruelty was not sated until he saw the man's limbs, members, and bowels dragged through the streets and heaped up before him.

“He seldom had anyone put to death except by numerous slight wounds, his constant order, which soon became well-known, being: "Strike so that he may feel that he is dying." When a different man than he had intended had been killed, through a mistake in the names, he said that the victim too had deserved the same fate. He often uttered the familiar line of the tragic poet [Accius, Trag., 203]: — "Let them hate me, so they but fear me." He often inveighed against all the senators alike, as adherents of Seianus and informers against his mother and brothers, producing the documents which he pretended to have burned, and upholding the cruelty of Tiberius as forced upon him, since he could not but believe so many accusers. He constantly tongue-lashed the equestrian order as devotees of the stage and the arena. Angered at the rabble for applauding a faction which he opposed, he cried: "I wish the Roman people had but a single neck," and when the brigand Tetrinius was demanded, he said that those who asked for him were Tetriniuses also. Once a band of five retiarii in tunics, matched against the same number of secutores, yielded without a struggle; but when their death was ordered, one of them caught up his trident and slew all the victors. Caligula bewailed this in a public proclamation as a most cruel murder, and expressed his horror of those who had had the heart to witness it

“As a sample of his humor, he took his place beside a statue of Jupiter, and asked the tragic actor Apelles which of the two seemed to him the greater, and when he hesitated, Caligula had him flayed with whips, extolling his voice from time to time, when the wretch begged for mercy, as passing sweet even in his groans. Whenever he kissed the neck of his wife or sweetheart, he would say: "Off comes this beautiful head whenever I give the word." He even used to threaten now and then that he would resort to torture if necessary, to find out from his dear Caesonia why he loved her so passionately.”

orgy of Tiberius's Capri

Claudius’s Cruelty and Suspicion

Suetonius wrote: “That he was of a cruel and bloodthirsty disposition was shown in matters great and small.He always exacted examination by torture and the punishment of parricides at once and in his presence. When he was at Tibur and wished to see an execution in the ancient fashion, no executioner could be found after the criminals were bound to the stake. Whereupon he sent to fetch one from the city and continued to wait for him until nightfall. At any gladiatorial show, either his own or another's, he gave orders that even those who fell accidentally should be slain, in particularly the net-fighters [Their faces were not covered by helmets] so that he could watch their faces as they died. When a pair of gladiators had fallen by mutually inflicted wounds, he at once had some little knives made from both their swords for his use [According to Pliny, Nat. Hist. 28.34, game killed with a knife with which a man had been slain was a specific for epilepsy]. He took such pleasure in the combats with wild beasts and of those that fought at noonday that he would go down to the arena at daybreak and after dismissing the people for luncheon at midday, he would keep his seat and in addition to the appointed combatants, he would for trivial and hasty reasons match others, even of the carpenters, the assistants, and men of that class, if any automatic device, or pageant [A structure with several movable stories, for show pieces and other stage effects; see Juv. 4.122], or anything else of the kind, had not worked well. He even forced one of his pages to enter the arena just as he was, in his toga. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum:Claudius” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Claudius”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“But there was nothing for which he was so notorious as timidity and suspicion. Although in the early days of his reign, as we have said, he made a display of simplicity, he never ventured to go to a banquet without being surrounded by guards with lances and having his soldiers wait upon him in place of the servants; and he never visited a man who was in without having the patient's room examined beforehand and his pillows and bed-clothing felt over and shaken out. Afterwards he even subjected those who came to pay their morning calls to search, sparing none the strictest examination. Indeed, it was not until late, and then reluctantly, that he gave up having women and young boys and girls grossly mishandled, and the cases for pens and styluses taken from every man's attendant or scribe. When Camillus began his revolution, he felt sure that Claudius could be intimidated without resorting to war; and in fact when he ordered the emperor in an insulting, threatening, and impudent letter to give up his throne and betake himself to a life of privacy and retirement, Claudius called together the leading men and asked their advice about complying.

“He was so terror-stricken by unfounded reports of conspiracies, that he tried to abdicate. When, as I have mentioned before, a man with a dagger was caught near him as he was sacrificing, he summoned the Senate in haste by criers and loudly and tearfully bewailed his lot, saying that there was no safety for him anywhere; and for a long time he should not appear in public. His ardent love for Messalina too was cooled, not so much by her unseemly and insulting conduct, as through fear of dangers, since he believed that her paramour Silius aspired to the throne. On that occasion he made a shameful and cowardly flight to the camp [Of the Praetorian Guard, in the northeastern part of the city], doing nothing all the way but ask whether his throne was secure.

“No suspicion was too trivial, nor the inspirer of it too insignificant, to drive him on to precaution and vengeance, once a slight uneasiness entered his mind. One of two parties to a suit, when he made his morning call, took Claudius aside, and said that he had dreamed that he was murdered by someone; then a little later pretending to recognize the assassin, he pointed out his opponent, as he was handing in his petition. The latter was immediately seized, as if caught red-handed, and hurried off to execution. It was in a similar way, they say, that Appius Silanus met his downfall. When Messalina and Narcissus had put their heads together to destroy him, they agreed on their parts and the latter rushed into his patron's bed-chamber before daybreak in pretended consternation, declaring that he had dreamed that Appius had made an attack on the emperor. Then Messalina, with assumed surprise, declared that she had had the same dream for several successive nights. A little later, as had been arranged, Appius, who had received orders the day before to come at that time, was reported to be forcing his way in, and as if this were proof positive of the truth of the dream, his immediate accusation and death were ordered. And Claudius did not hesitate to recount the whole affair to the Senate next day and to thank the freedman [Narcissus] for watching over his emperor's safety even in his sleep.”

Awful Things Nero Did

Nero (A.D. 37-68) was the fifth emperor of Rome, ruling from A.D. 54 to 68. He became the Roman emperor when he was seventeen, the youngest ever at that time. Nero's real name was Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. He is known mainly for being a cruel wacko but in many ways he left the Roman Empire better off than when arrived.

In his book “Nero,” Edward Champlin wrote: “Nero murdered his mother, and Nero fiddled while Rome burned. Nero also slept with his mother, Nero married and executed one stepsister, executed his other stepsister, raped and murdered his stepbrother. In fact, he executed or murdered most of his close relatives. He kicked his pregnant wife to death. He castrated and then married a freedman. He married another freedman, this time himself playing the bride. He raped a vestal virgin. He melted down the household gods of Rome for their cash value."

“After incinerating the city in 64, he built over much of downtown Rome with his own great Xanadu, the Golden House. He fixed the blame for the Great Fire on the Christians, some of whom he hung up as human torches to light his gardens at night. He competed as a poet, singer an actor, a herald and charioteer, and he won every contest, even when he fell out of his chariot at the Olympics games, he alienated and persecuted the elite, neglected the army, and drained the treasury. And he committed suicide at the age of 30, one step ahead of his executioners. His last words were, “What an artist died in me!”

Nero’s worst enemies were in his own family and household. The intrigues of his unscrupulous and ambitious mother, Agrippina, to displace Nero and elevate Britannicus, the son of Claudius, led to Nero’s first domestic tragedy—the poisoning of Britannicus. He afterward yielded himself to the influence of the infamous Poppaea Sabina, said to be the most beautiful and the wickedest woman of Rome. At her suggestion, he first murdered his mother, and then his wife. He discarded the counsels of Seneca and Burrhus, and accepted those of Tigellinus, described a man of the worst character. Then followed a career of wickedness, extortion, and atrocious cruelty. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~]

Patrick Ryan wrote in Listverse, Nero “ murdered thousands of people including his aunt, stepsister, ex-wife, mother, wife and stepbrother. Some were killed in searing hot baths. He poisoned, beheaded, stabbed, burned, boiled, crucified and impaled people. He often raped women and cut off the veins and private parts of both men and women. Thousands of Christians were starved to death, burned, torn by dogs, fed to lions, crucified, used as torches and nailed to crosses. He was so bad that many of the Christians thought he was the Antichrist. He even tortured and killed the apostle Paul and the disciple Peter. Paul was beheaded and Peter was crucified upside down.” [Source: Patrick Ryan, Listverse, May 30, 2012]

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic: “He instructed his mentor Seneca to commit suicide (which he solemnly did); castrated and then married a teenage boy; presided over the wholesale arson of Rome in A.D. 64 and then shifted the blame to a host of Christians (including Saints Peter and Paul), who were rounded up and beheaded or crucified and set aflame so as to illuminate an imperial festival. The case against Nero as evil incarnate would appear to be open and shut.” [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, September 2014 ~]

Did Nero Get a Bad Rap?

Locusta testing a poison for Nero

Now some scholars say Nero wasn’t all bad. After describing his alleged crimes, Champlin spends much of the rest of his book examining whether Nero was indeed the monster he was made out to be. He points out the stories of Nero's legendary exploits come mainly from the work of three writers — the historians Tacitus and L. Casius Dio and the biographer Suetonius — whose own sources appear to have been hearsay, public record long since lost and the works of “several lost authors," including Pliny the Elder and Cluvius Rufus. The accounts of the three writers are often inconsistent and sometime contradictory.

Champlin said he was not out to “whitewash” Nero: “He was a bad man and a bad ruler. But there is strong evidence to suggest that our dominant sources have misrepresented him badly, creating the image of the unbalanced, egomaniacal monster, vividly enhanced by Christian writers, that has so dominated the shocked imagination of the Western tradition for two millennia, The reality was more complex."

Champlain makes a case that Nero had “had an afterlife that was unique in antiquity." Like Alexander the Great or even Jesus Christ, he was widely seen in the popular imagination as “the man who has not died but will return, and the man who died but whose reputation is a powerful living force” and was thus — a man who was very much missed." The “evolution of a historical person into a folkloric hero says little about the actual person but much about what some people believe...The immortal hero of the folklore embodies a longing for the past and explanation of the present, and most powerfully, a justification for the future." Nero comes across more as a skillful performer on the public stage with “a fondness for pleasure among low company so strong as to identification with masses."

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic: “Almost certainly the Roman Senate ordered the expunging of Neronian influence for political reasons. Perhaps it was that his death was followed by outpourings of public grief so widespread that his successor Otho hastily renamed himself Otho Nero. Perhaps it was because mourners long continued to bring flowers to his tomb, and the site was said to be haunted until, in 1099, a church was erected on top of his remains in the Piazza del Popolo. Or perhaps it was due to the sightings of “false Neros” and the persistent belief that the boy king would one day return to the people who so loved him. [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, September 2014 ~]

“The dead do not write their own history. Nero’s first two biographers, Suetonius and Tacitus, had ties to the elite Senate and would memorialize his reign with lavish contempt. The notion of Nero’s return took on malevolent overtones in Christian literature, with Isaiah’s warning of the coming Antichrist: “He will descend from his firmament in the form of a man, a king of iniquity, a murderer of his mother.” Later would come the melodramatic condemnations: the comic Ettore Petrolini’s Nero as babbling lunatic, Peter Ustinov’s Nero as the cowardly murderer, and the garishly enduring tableau of Nero fiddling while Rome burns. What occurred over time was hardly erasure but instead demonization. A ruler of baffling complexity was now simply a beast. ~

““Today we condemn his behavior,” says archaeological journalist Marisa Ranieri Panetta. “But look at the great Christian emperor Constantine. He had his first son, his second wife, and his father-in-law all murdered. One can’t be a saint and the other a devil. Look at Augustus, who destroyed a ruling class with his blacklists. Rome ran in rivers of blood, but Augustus was able to launch effective propaganda for everything he did. He understood the media. And so Augustus was great, they say. Not to suggest that Nero was himself a great emperor—but that he was better than they said he was, and no worse than those who came before and after him.” ~

Nero's Cruelty and Wantonness

When Nero was 25, after reigning for fiver years, his personality changed dramatically and he turned into a fiend and a ruthless killer. He murdered his brother, his pregnant wife, and his mother who he had tried to assassinate five times before finally achieving success. Nero continued down this ruthless and murderous path for the rest of his short life. He forced his successful generals to commit suicide and tortured and executed suspected plotters. His tutor Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 B.C." 65 AD), who had dominated Nero's court, was forced to commit suicide at Nero's command. Some have blamed Nero despicable behavior on his childhood. After his father died he was brought up in the home of his deranged uncle Caligula and raised by his "impetuous and deranged mother"Agrippina the Younger, who used "incest and murder" to secure him the throne over the rightful heir and eliminated rivals in her son's path to the emperorship by poisoning their food, it is said, with a toxin extracted from a shell-less mollusk known as a sea hare.

Suetonius wrote: “Although at first his acts of wantonness, lust, extravagance, avarice and cruelty were gradual and secret, and might be condoned as follies of youth, yet even then their nature was such that no one doubted that they were defects of his character and not due to his time of life. No sooner was twilight over than he would catch up a cap or a wig and go to the taverns or range about the streets playing pranks, which however were very far from harmless; for he used to beat men as they came home from dinner, stabbing any who resisted him and throwing them into the sewers. He would even break into shops and rob them, setting up a market in the Palace, where he divided the booty which he took, sold it at auction, and then squandered the proceeds. In the strife which resulted he often ran the risk of losing his eyes or even his life, for he was beaten almost to death by a man of the senatorial order whose wife he had maltreated. Warned by this, he never afterwards ventured to appear in public at that hour without having tribunes follow him at a distance and unobserved. Even in the daytime he would be carried privately to the theater in a litter, and from the upper part of the proscenium would watch the brawls of the pantomimic actors and egg them on; and when they came to blows and fought with stones and broken benches, he himself threw many missiles at the people and even broke a praetor's head. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“Little by little, however, as his vices grew stronger, he dropped jesting and secrecy and with no attempt at disguise openly broke out into worse crime. He prolonged his revels from midday to midnight, often livening himself by a warm plunge, or, if it were summer, into water cooled with snow. Sometimes, too, he closed the inlets and banqueted in public in the great tank in the Campus Martius, or in the Circus Maximus, waited on by harlots and dancing girls from all over the city. Whenever he drifted down the Tiber to Ostia, or sailed about the Gulf of Baiae, booths were set up at intervals along the banks and shores, fitted out for debauchery, while bartering matrons played the part of inn-keepers and from every hand solicited him to come ashore. He also levied dinners on his friends, one of whom spent four million sesterces for a banquet at which turbans were distributed, and another a considerably larger sum for a rose dinner.

Nero’s Kills Off His Family

Poppea, Nero's second wife, brings Nero the head of Octavia, his first wife

Suetonius wrote: “He began his career of parricide and murder with Claudius, for even if he was not the instigator of the emperor's death, he was at least privy to it, as he openly admitted; for he used afterwards to laud mushrooms, the vehicle in which the poison was administered to Claudius, as "the food of the gods, as the Greek proverb has it." At any rate, after Claudius' death he vented on him every kind of insult, in act and word, charging him now with folly and now with cruelty; for it was a favorite joke of his to say that Claudius had ceased "to play the fool among mortals," lengthening the first syllable of the word morari, and he disregarded many of his decrees and acts as the work of a madman and a dotard. Finally, he neglected to enclose the place where his body was burned except with a low and mean wall. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“He attempted the life of Britannicus by poison, not less from jealousy of his voice (for it was more agreeable than his own) than from fear that he might sometime win a higher place than himself in the people's regard because of the memory of his father. He procured the potion from an arch-poisoner, one Locusta, and when the effect was slower than he anticipated, merely physicking Britannicus, he called the woman to him and flogged her with his own hand, charging that she had administered a medicine instead of a poison; and when she said in excuse that she had given a smaller dose to shield him from the odium of the crime, he replied: "It's likely that I am afraid of the Julian law;" and he forced her to mix as swift and instant a potion as she knew how in his own room before his very eyes. Then he tried it on a kid, and as the animal lingered for five hours, had the mixture steeped again and again and threw some of it before a pig. The beast instantly fell dead, whereupon he ordered that the poison be taken to the dining-room and given to Britannicus. The boy dropped dead at the very first taste, but Nero lied to his guests and declared that he was seized with the falling sickness, to which he was subject, and the next day had him hastily and unceremoniously buried in a pouring rain. He rewarded Locusta for her eminent services with a full pardon and large estates in the country, and actually sent her pupils.

Nero and His Mother, Agrippina

Suetonius wrote: “His mother offended him by too strict surveillance and criticism of his words and acts, but at first he confined his resentment to frequent endeavors to bring upon her a burden of unpopularity by pretending that he would abdicate the throne and go off to Rhodes. Then depriving her of all her honors and of her guard of Roman and German soldiers, he even forbade her to live with him and drove her from the Palace. After that he passed all bounds in harrying her, bribing men to annoy her with lawsuits while she remained in the city, and after she had retired to the country, to pass her house by land and sea and break her rest with abuse and mockery. At last terrified by her violence and threats, he determined to have her life, and after thrice attempting it by poison and finding that she had made herself immune by antidotes, he tampered with the ceiling of her bedroom, contriving a mechanical device for loosening its panels and dropping them upon her while she slept. When this leaked out through some of those connected with the plot, he devised a collapsible boat to destroy her by shipwreck or by the falling in of its cabin. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“Then he pretended a reconciliation and invited her in a most cordial letter to come to Baiae and celebrate the feast of Minerva with him. On her arrival, instructing his captains to wreck the galley in which she had come, by running into it as if by accident, he detained her at a banquet, and when she would return to Bauli, offered her his contrivance in place of the craft which had been damaged, escorting her to it in high spirits and even kissing her breasts as they parted. The rest of the night he passed sleepless in intense anxiety, awaiting the outcome of his design. On learning that everything had gone wrong and that she had escaped by swimming, driven to desperation he secretly had a dagger thrown down beside her freedman Lucius Agelmus, when he joyfully brought word that she was safe and sound, and then ordered that the freedman be seized and bound, on the charge of being hired to kill the emperor; that his mother be put to death, and the pretense made that she had escaped the consequences of her detected guilt by suicide. Trustworthy authorities add still more gruesome details: that he hurried off to view the corpse, handled her limbs, criticizing some and commending others, and that becoming thirsty meanwhile, he took drink. Yet he could not either then or ever afterwards endure the stings of conscience though soldiers, Senate and people tried to hearten him with their congratulations; for he often owned that he was hounded by his mother's ghost and by the whips and blazing torches of the Furies.

“He even had rites performed by the Magi, in the effort to summon her shade and entreat it for forgiveness. Moreover, in his journey through Greece he did not venture to take part in the Eleusinian mysteries, since at the beginning the godless and wicked are warned by the herald's proclamation to go hence. To matricide he added the murder of his aunt. When he once visited her as she was confined to her bed from costiveness, and she, as old ladies will, stroking his downy beard (for he was already well grown) happened to say fondly: "As soon as I receive this [that is, "when I see you arrived at man's estate." The first shaving of the beard by a young Roman was a symbolic act, usually performed at the age of twenty-one with due ceremony. According to Tac. Ann. 14.15, and Dio 61.19, Nero first shaved his beard in 59 A.D., at the age of twenty-one and commemorated the event by establishing the Juvenalia], I shall gladly die," he turned to those with him and said as if in jest: "I'll take it off at once." Then he bade the doctors give the sick woman an overdose of physic and seized her property before she was cold, suppressing her will, that nothing might escape him.”

Incest of Agrippina and Nero

Nero and Agrippina

Tacitus wrote: “The author Cluvius writes that Agrippina took her desire to keep power so far as to offer herself more often to a drunken Nero, all dressed up and ready for incest. She did this at midday when Nero was already warmed up with wine and food. Those close to both had seen passionate kisses and sensual caresses, which seemed to imply wrongdoing. It was then that Seneca who looked for a woman’s help against this woman’s charms, introduced Acte to Nero. This freedwoman who was anxious because of the danger to herself and the damage to Nero’s reputation, told Nero that the incest was well known since Agrippina boasted about it. She added that the soldiers would not tolerate the rule of such a wicked emperor. [Source: Tacitus (b.56/57-after 117 A.D.): “Annals” Murder of Agrippina. Book 14, Chapters 1-12 , John D Clare's History Blog, johndclare.net/AncientHistory/Agrippina

“Cluvius relates that Agrippina in her eagerness to retain her influence went so far that more than once at midday, when Nero, even at that hour, was flushed with wine and feasting, she presented herself attractively attired to her half intoxicated son and offered him her person, and that when kinsfolk observed wanton kisses and caresses, portending infamy, it was Seneca who sought a female's aid against a woman's fascinations, and hurried in Acte, the freed-girl, who alarmed at her own peril and at Nero's disgrace, told him that the incest was notorious, as his mother boasted of it, and that the soldiers would never endure the rule of an impious sovereign.

“Fabius Rusticus writes that it was not Agrippina, but Nero, who was eager for incest, and that the clever action of the same freedwoman prevented it. A number of other authors agree with Cluvius and general opinion follows this view. Possibly Agrippina really planned such a great wickedness, perhaps because the consideration of a new act of lust seemed more believable in a woman who as a girl had allowed herself to be seduced by Lepidus in the hope of gaining power; this same desire had led her to lower herself so far as to become the lover of Pallas, and had trained herself for any evil act by her marriage to her uncle.

“No one doubted that he wanted sexual relations with his own mother, and was prevented by her enemies, afraid that this ruthless and powerful woman would become too strong with this sort of special favour. What added to this opinion was that he included among his mistresses a certain prostitute who they said looked very like Agrippina. They also say that, whenever he rode in a litter with his mother, the stains on his clothes afterwards proved that he had indulged in incest with her.

Murder of Agrippina

Cambridge classic professor Mary Beard told an interviewer that Tacitus's account of Agrippina murder in “The Annals” is some of the best history ever written. “There is no better story than Nero's attempts to murder his mother with whom he is finally very pissed off! Nero the mad boy emperor decides that he is going to get rid of mum by a rather clever collapsible boat. He has her to dinner, waves her fondly farewell. The boat collapses. Sadly for Nero, his mum, Agrippina, is a very strong swimmer and she makes it to the land and back home. And she's clever, she knows boats don't just collapse like that — it was a completely calm night, so she works out Nero was out to get her. She knows things are going to end badly. Nero can't let her off, so he sends round the tough guys to murder her. Agrippina looks them in the eye and says, “Strike me in the belly with your sword." There are two things going on. One is: my son who came out of my belly is trying to murder me. But the other thing we know is that they were widely reputed to have had an incestuous relationship in the earlier days. So it's not just Nero the son murdering his mother, but Nero the lover murdering his discarded mistress. And if you read Robert Graves's I, Claudius, some of it comes directly from this." When asked if Tacitus's account is better than a Hollywood plot, Beard said, “Yes but it's not just that. What he does is seduce you with an extraordinary tale...very exciting. But, actually, he wants to talk about the corruption of autocracy. It's about one-man rule going bad."

Tacitus wrote: “In the year of the consulship of Caius Vipstanus and Caius Fonteius, Nero deferred no more a long meditated crime. Length of power had matured his daring, and his passion for Poppaea daily grew more ardent. As the woman had no hope of marriage for herself or of Octavia's divorce while Agrippina lived, she would reproach the emperor with incessant vituperation and sometimes call him in jest a mere ward who was under the rule of others, and was so far from having empire that he had not even his liberty. "Why," she asked, "was her marriage put off? Was it, forsooth, her beauty and her ancestors, with their triumphal honours, that failed to please, or her being a mother, and her sincere heart? No; the fear was that as a wife at least she would divulge the wrongs of the Senate, and the wrath of the people at the arrogance and rapacity of his mother. If the only daughter-in-law Agrippina could bear was one who wished evil to her son, let her be restored to her union with Otho. She would go anywhere in the world, where she might hear of the insults heaped on the emperor, rather than witness them, and be also involved in his perils." [Source: P. Cornelius Tacitus, “The Annals,” Book XIV, A.D. 59-62 A.D. 109, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb]

“These and the like complaints, rendered impressive by tears and by the cunning of an adulteress, no one checked, as all longed to see the mother's power broken, while not a person believed that the son's hatred would steel his heart to her murder. Nero accordingly avoided secret interviews with her, and when she withdrew to her gardens or to her estates at Tusculum and Antium, he praised her for courting repose. At last, convinced that she would be too formidable, wherever she might dwell, he resolved to destroy her, merely deliberating whether it was to be accomplished by poison, or by the sword, or by any other violent means. Poison at first seemed best, but, were it to be administered at the imperial table, the result could not be referred to chance after the recent circumstances of the death of Britannicus. Again, to tamper with the servants of a woman who, from her familiarity with crime, was on her guard against treachery, appeared to be extremely difficult, and then, too, she had fortified her constitution by the use of antidotes. How again the dagger and its work were to be kept secret, no one could suggest, and it was feared too that whoever might be chosen to execute such a crime would spurn the order.”

Plan to Kill Agrippina

Nero ordering the death of his mother

Tacitus wrote: “An ingenious suggestion was offered by Anicetus, a freedman, commander of the fleet at Misenum, who had been tutor to Nero in boyhood and had a hatred of Agrippina which she reciprocated. He explained that a vessel could be constructed, from which a part might by a contrivance be detached, when out at sea, so as to plunge her unawares into the water. "Nothing," he said, "allowed of accidents so much as the sea, and should she be overtaken by shipwreck, who would be so unfair as to impute to crime an offence committed by the winds and waves? The emperor would add the honour of a temple and of shrines to the deceased lady, with every other display of filial affection." [Source: P. Cornelius Tacitus, “The Annals,” Book XIV, A.D. 59-62 A.D. 109, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb]

“Nero liked the device, favoured as it also was by the particular time, for he was celebrating Minerva's five days' festival at Baiae. Thither he enticed his mother by repeated assurances that children ought to bear with the irritability of parents and to soothe their tempers, wishing thus to spread a rumour of reconciliation and to secure Agrippina's acceptance through the feminine credulity, which easily believes what joy. As she approached, he went to the shore to meet her (she was coming from Antium), welcomed her with outstretched hand and embrace, and conducted her to Bauli. This was the name of a country house, washed by a bay of the sea, between the promontory of Misenum and the lake of Baiae.

“Here was a vessel distinguished from others by its equipment, seemingly meant, among other things, to do honour to his mother; for she had been accustomed to sail in a trireme, with a crew of marines. And now she was invited to a banquet, that night might serve to conceal the crime. It was well known that somebody had been found to betray it, that Agrippina had heard of the plot, and in doubt whether she was to believe it, was conveyed to Baiae in her litter. There some soothing words allayed her fear; she was graciously received, and seated at table above the emperor. Nero prolonged the banquet with various conversation, passing from a youth's playful familiarity to an air of constraint, which seemed to indicate serious thought, and then, after protracted festivity, escorted her on her departure, clinging with kisses to her eyes and bosom, either to crown his hypocrisy or because the last sight of a mother on the even of destruction caused a lingering even in that brutal heart.”

Bungled Murder of Agrippina

Tacitus wrote: “A night of brilliant starlight with the calm of a tranquil sea was granted by heaven, seemingly, to convict the crime. The vessel had not gone far, Agrippina having with her two of her intimate attendants, one of whom, Crepereius Gallus, stood near the helm, while Acerronia, reclining at Agrippina's feet as she reposed herself, spoke joyfully of her son's repentance and of the recovery of the mother's influence, when at a given signal the ceiling of the place, which was loaded with a quantity of lead, fell in, and Crepereius was crushed and instantly killed. Agrippina and Acerronia were protected by the projecting sides of the couch, which happened to be too strong to yield under the weight. But this was not followed by the breaking up of the vessel; for all were bewildered, and those too, who were in the plot, were hindered by the unconscious majority. The crew then thought it best to throw the vessel on one side and so sink it, but they could not themselves promptly unite to face the emergency, and others, by counteracting the attempt, gave an opportunity of a gentler fall into the sea. Acerronia, however, thoughtlessly exclaiming that she was Agrippina, and imploring help for the emperor's mother, was despatched with poles and oars, and such naval implements as chance offered. Agrippina was silent and was thus the less recognized; still, she received a wound in her shoulder. She swam, then met with some small boats which conveyed her to the Lucrine lake, and so entered her house. [Source: P. Cornelius Tacitus, “The Annals,” Book XIV, A.D. 59-62 A.D. 109, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb]

death of Agrippina

“There she reflected how for this very purpose she had been invited by a lying letter and treated with conspicuous honour, how also it was near the shore, not from being driven by winds or dashed on rocks, that the vessel had in its upper part collapsed, like a mechanism anything but nautical. She pondered too the death of Acerronia; she looked at her own wound, and saw that her only safeguard against treachery was to ignore it. Then she sent her freedman Agerinus to tell her son how by heaven's favour and his good fortune she had escaped a terrible disaster; that she begged him, alarmed, as he might be, by his mother's peril, to put off the duty of a visit, as for the present she needed repose. Meanwhile, pretending that she felt secure, she applied remedies to her wound, and fomentations to her person. She then ordered search to be made for the will of Acerronia, and her property to be sealed, in this alone throwing off disguise.

“Nero, meantime, as he waited for tidings of the consummation of the deed, received information that she had escaped with the injury of a slight wound, after having so far encountered the peril that there could be no question as to its author. Then, paralysed with terror and protesting that she would show herself the next moment eager for vengeance, either arming the slaves or stirring up the soldiery, or hastening to the Senate and the people, to charge him with the wreck, with her wound, and with the destruction of her friends, he asked what resource he had against all this, unless something could be at once devised by Burrus and Seneca. He had instantly summoned both of them, and possibly they were already in the secret. There was a long silence on their part; they feared they might remonstrate in vain, or believed the crisis to be such that Nero must perish, unless Agrippina were at once crushed. Thereupon Seneca was so far the more prompt as to glance back on Burrus, as if to ask him whether the bloody deed must be required of the soldiers. Burrus replied "that the praetorians were attached to the whole family of the Caesars, and remembering Germanicus would not dare a savage deed on his offspring. It was for Anicetus to accomplish his promise."

“Anicetus, without a pause, claimed for himself the consummation of the crime. At those words, Nero declared that that day gave him empire, and that a freedman was the author of this mighty boon. "Go," he said, "with all speed and take with you the men readiest to execute your orders." He himself, when he had heard of the arrival of Agrippina's messenger, Agerinus, contrived a theatrical mode of accusation, and, while the man was repeating his message, threw down a sword at his feet, then ordered him to be put in irons, as a detected criminal, so that he might invent a story how his mother had plotted the emperor's destruction and in the shame of discovered guilt had by her own choice sought death.

“Meantime, Agrippina's peril being universally known and taken to be an accidental occurrence, everybody, the moment he heard of it, hurried down to the beach. Some climbed projecting piers; some the nearest vessels; others, as far as their stature allowed, went into the sea; some, again, stood with outstretched arms, while the whole shore rung with wailings, with prayers and cries, as different questions were asked and uncertain answers given. A vast multitude streamed to the spot with torches, and as soon as all knew that she was safe, they at once prepared to wish her joy, till the sight of an armed and threatening force scared them away. Anicetus then surrounded the house with a guard, and having burst open the gates, dragged off the slaves who met him, till he came to the door of her chamber, where a few still stood, after the rest had fled in terror at the attack. A small lamp was in the room, and one slave-girl with Agrippina, who grew more and more anxious, as no messenger came from her son, not even Agerinus, while the appearance of the shore was changed, a solitude one moment, then sudden bustle and tokens of the worst catastrophe. As the girl rose to depart, she exclaimed, "Do you too forsake me?" and looking round saw Anicetus, who had with him the captain of the trireme, Herculeius, and Obaritus, a centurion of marines. "If," said she, "you have come to see me, take back word that I have recovered, but if you are here to do a crime, I believe nothing about my son; he has not ordered his mother's murder."

“The assassins closed in round her couch, and the captain of the trireme first struck her head violently with a club. Then, as the centurion bared his sword for the fatal deed, presenting her person, she exclaimed, "Smite my womb," and with many wounds she was slain.”

Nero’s Reaction to His Mother’s Death

Nero checking his mother's corpse

Tacitus wrote: “So far our accounts agree. That Nero gazed on his mother after her death and praised her beauty, some have related, while others deny it. Her body was burnt that same night on a dining couch, with a mean funeral; nor, as long as Nero was in power, was the earth raised into a mound, or even decently closed. Subsequently, she received from the solicitude of her domestics, a humble sepulchre on the road to Misenum, near the country house of Caesar the Dictator, which from a great height commands a view of the bay beneath. As soon as the funeral pile was lighted, one of her freedmen, surnamed Mnester, ran himself through with a sword, either from love of his mistress or from the fear of destruction. [Source: P. Cornelius Tacitus, “The Annals,” Book XIV, A.D. 59-62 A.D. 109, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb]

“Many years before Agrippina had anticipated this end for herself and had spurned the thought. For when she consulted the astrologers about Nero, they replied that he would be emperor and kill his mother. "Let him kill her," she said, "provided he is emperor."

“But the emperor, when the crime was at last accomplished, realised its portentous guilt. The rest of the night, now silent and stupified, now and still oftener starting up in terror, bereft of reason, he awaited the dawn as if it would bring with it his doom. He was first encouraged to hope by the flattery addressed to him, at the prompting of Burrus, by the centurions and tribunes, who again and again pressed his hand and congratulated him on his having escaped an unforeseen danger and his mother's daring crime. Then his friends went to the temples, and, an example having once been set, the neighbouring towns of Campania testified their joy with sacrifices and deputations. He himself, with an opposite phase of hypocrisy, seemed sad, and almost angry at his own deliverance, and shed tears over his mother's death. But as the aspects of places change not, as do the looks of men, and as he had ever before his eyes the dreadful sight of that sea with its shores (some too believed that the notes of a funereal trumpet were heard from the surrounding heights, and wailings from the mother's grave), he retired to Neapolis and sent a letter to the Senate, the drift of which was that Agerinus, one of Agrippina's confidential freedmen, had been detected with the dagger of an assassin, and that in the consciousness of having planned the crime she had paid its penalty.”

Nero’s Cruelty Outside His Family

Suetonius wrote: “Those outside his family he assailed with no less cruelty. It chanced that a comet [Tacitus mentions two comets, one in 60 and the other in 64; see Ann. 14.22, 15.47] had begun to appear on several successive nights, a thing which is commonly believed to portend the death of great rulers. Worried by this, and learning from the astrologer Balbillus that kings usually averted such omens by the death of some distinguished man, thus turning them from themselves upon the heads of the nobles, he resolved on the death of all the eminent men of the State; but the more firmly, and with some semblance of justice, after the discovery of two conspiracies. The earlier and more dangerous of these was that of Piso at Rome; the other was set on foot by Vinicius at Beneventum and detected there. The conspirators made their defense in triple sets of fetters, some voluntarily admitting their guilt, some even making a favor of it, saying that there was no way except by death that they could help a man disgraced by every kind of wickedness. The children of those who were condemned were banished or put to death by poison or starvation; a number are known to have been slain all together at a single meal along with their preceptors and attendants, while others were prevented from earning their daily bread. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“After this he showed neither discrimination nor moderation in putting to death whomsoever he pleased on any pretext whatever. To mention but a few instances, Salvidienus Orfitus was charged with having let to certain states as headquarters three shops which formed part of his home near the Forum; Cassius Longinus, a blind jurist, with retaining in the old family tree of his House the mask of Gaius Cassius, the assassin of Julius Caesar; Paetus Thrasea with having a sullen mien, like that of a preceptor. To those who were bidden to die he never granted more than an hour's respite, and to avoid any delay, he brought physicians who were at once to "attend to" such as lingered; for that was the term he used for killing them by opening their veins. It is even believed that it was his wish to throw living men to be torn to pieces and devoured by a monster of Egyptian birth, who would crunch raw flesh and anything else that was given him. Transported and puffed up with such successes, as he considered them, he boasted that no princeps had ever known what power he really had, and he often threw out unmistakable hints that he would not spare even those of the Senate who survived, but would one day blot out the whole order from the State and hand over the rule of the provinces and the command of the armies to the Roman equites and to his freedmen. Certain it is that neither on beginning a journey nor on returning did he kiss any member or even return his greeting; and at the formal opening of the work at the Isthmus the prayer which he uttered in a loud voice before a great throng was that the event might result favorably "for himself and the people of Rome," thus suppressing any mention of the Senate.

Nero's remorse

“But he showed no greater mercy to the people or the walls of his capital. When someone in a general conversation said: "When I am dead, be earth consumed by fire," he rejoined "Nay, rather while I live," and his action was wholly in accord. For under cover of displeasure at the ugliness of the old buildings and the narrow, crooked streets, he set fire to the city so openly that several ex-consuls did not venture to lay hands on his chamberlains although they caught them on their estates with tow and firebrands, while some granaries near the Golden House, whose room he particularly desired, were demolished by engines of war and then set on fire, because their walls were of stone. For six days and seven nights destruction raged, while the people were driven for shelter to monuments and tombs. At that time, besides an immense number of dwellings, the houses of leaders of old were burned, still adorned with trophies of victory, and the temples of the gods vowed and dedicated by the kings and later in the Punic and Gallic wars, and whatever else interesting and noteworthy had survived from antiquity. Viewing the conflagration from the tower of Maecenas, and exulting, as he said, "with the beauty of the flames," he sang the whole time the "Sack of Ilium," in his regular stage costume. Furthermore, to gain from this calamity too the spoil and booty possible, while promising the removal of the debris and dead bodies free of cost, allowed no one to approach the ruins of his own property; and from the contributions which he not only received, but even demanded, he nearly bankrupted the provinces and exhausted the resources of individuals.”

Domitian’s Cruelty

Suetonius wrote: “But he did not continue this course of mercy or integrity, although he turned to cruelty somewhat more speedily than to avarice. He put to death a pupil of the pantomimic actor Paris, who was still a beardless boy and ill at the time, because in his skill and his appearance he seemed not unlike his master; also Hermogenes of Tarsus because of some allusions in his History, besides crucifying even the slaves who had written it out. A householder who said that a Thracian gladiator was a match for the murmillo, but not for the giver of the games, he caused to be dragged from his seat and thrown into the arena to dogs, with this placard: "A favorer of the Thracians who spoke impiously." [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum: Domitian,” (“Life of Domitian”), written c. A.D. 110, translated by J. C. Rolfe, Suetonius, 2 Vols., The Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.339-385]

“He put to death many senators, among them several ex-consuls, including Civica Cerealis, at the very time when he was proconsul in Asia; Salvidienus Orfitus; Acilius Glabrio, while he was in exile — these on the ground of plotting revolution, the rest on any charge, however trivial. He slew Aelius Lamia for joking remarks, which were reflections on him, it is true, but made long before and harmless. For when Domitian had taken away Lamia's wife, the latter replied to someone who praised his voice: "I practice continence"; and when Titus urged him to marry again, he replied: "Are you too looking for a wife?" He put to death Salvius Cocceianus, because he had kept the birthday of the emperor Otho, his paternal uncle; Mettius Pompusianus, because it was commonly reported that he had an imperial nativity and carried about a map of the world on parchment and speeches of the kings and generals from Titus Livius, besides giving two of his slaves the names of Mago and Hannibal; Sallustius Lucullus, governor of Britannia, for allowing some lances of a new pattern to be called "Lucullean," after his own name; Junius Rusticus, because he had published eulogies of Paetus Thrasea and Helvidius Priscus and called them the most upright of men; and on the occasion of this charge he banished all the philosophers from the city and from Italia.

Domitan

"He also executed the younger Helvidius, alleging that in a farce composed for the stage he had under the characters of Paris and Oenone censured Domitian's divorce from his wife; Flavinus Sabinus too, one of his cousins, because on the day of the consular elections the crier had inadvertently announced him to the people as emperor-elect, instead of consul. After his victory in the civil war he became even more cruel, and to discover any conspirators who were in hiding, tortured many of the opposite party by a new form of inquisition, inserting fire in their privates; and he cut off the hands of some of them. It is certain that of the more conspicuous only two were pardoned, a tribune of senatorial rank and a centurion, who the more clearly to prove their freedom from guilt, showed that they were of shameless unchastity and voted therefore have had no influence with the general or with the soldiers.

“His savage cruelty was not only excessive, but also cunning and sudden. He invited one of his stewards to his bed-chamber the day before crucifying him, made him sit beside him on his couch, and dismissed him in a secure and gay frame of mind, even deigning to send him a share of his dinner. When he was on the point of condemning the ex-consul Arrecinius Clemens, one of his intimates and tools, he treated him with as great favor as before, if not greater, and finally, as he was taking a drive with him, catching sight of his accuser, he said: "Pray, shall we hear this base slave tomorrow?" To abuse men's patience the more insolently, he never pronounced an unusually dreadful sentence without a preliminary declaration of clemency, so that there came to be no more certain indication of a cruel death than the leniency of his preamble. He had brought some men charged with treason into the Senate, and when he had introduced the matter by saying that he would find out that day how dear he was to the members, he had no difficulty in causing them to be condemned to suffer the ancient method of punishments. Then, appalled at the cruelty of the penalty, he interposed a veto, to lessen the odium, in these words (for it will be of interest to know his exact language): "Allow me, Fathers of the Senate, to prevail on you by your love for me to grant a favor which I know I shall obtain with difficulty, namely that you grant the condemned free choice of the manner of their death; for thus you will spare your own eyes and all men will know that I was present at the meeting of the Senate."

Commodus and the Film Gladiator

Commodus (ruled A.D. 177- 192, co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius from 177-180) was the vainglorious son of Marcus Aurelius who was assassinated in 192, ending the Antonine dynasty. He fancied himself as a great gladiator and battled opponents armed with lead swords that bent when they struck the emperor. Not surprisingly he ran up an impressive string of victories. Commodus finally lost on New Year's Eve, when he was strangled to death by a wrestler who had been dispatched by his rivals.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Marcus Aurelius' devotion to duty, protecting the frontiers of the empire, was in marked contrast to the behavior of his son, Commodus. In 180 A.D., Commodus abruptly abandoned the campaigns on the German frontier and returned to Rome. There, however, he alienated the Senate by resorting to government by means of favorites and identifying himself with the semidivine hero Hercules. By the time of his assassination in 192 A.D., Rome was in a chaotic state of affairs. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

Joaquin Phoenix played Commodus in the film Gladiator

Commodus was the emperor depicted in the film Gladiator . Edward Gibbons called him a man of “monstrous vices” and “unprovoked cruelty” and wrote: “His hours were spent in a seraglio of three hundred beautiful women, and as many boys, of every rank, and of every province; and whenever the arts of seduction proved ineffectual, the brutal lover had recourse to violence."

Commodus occasionally appeared in the arena during gladiator battles. He never put his life in danger and battled gladiators; instead he liked to decapitate ostriches with crescent-headed arrows. The crowds liked the show. They cheered and roared with laughter as the ostrich continued to run around after their heads were cut off. Once Commodus chopped off the head of an ostrich, and brandished its bloodied head and told senators the same fate awaited them if they went against him. Fearing for their lives, members of Commodus's court decided he had to go. A concubine slipped some poison into his wine and then a wrestler strangled him.

In the movie Gladiator Marcus Aurelius was played by Richard Harris and Commodus was played by Joaquin Phoenix. Contrary to impression given by the movie, Aurelius did no try to restore the republic, he had no general name Maximus (the Russell Crow character) and he was not killing by his son Commodus although the historian Cassius Dion said he was killed by doctors who wanted to “do a favor” for Commodus (most historians believe he died of an illness).

Film: Gladiator, directed by Ridley Scott and starring Russell Crowe.

Eusebius on Torture and Cruelty During the Diocletianic Persecution

In Chaper IV of “Martyrs of Palestine”, Eusebius wrote: Eusebius wrote: “Maximinus Caesar having come at that time into the government, as if to manifest to all the evidences of his reborn enmity against God, and of his impiety, armed himself for persecution against us more vigorously than his predecessors. In consequence, no little confusion arose among all, and they scattered here and there, endeavoring in some way to escape the danger; and there was great commotion everywhere. But what words would suffice for a suitable description of the Divine love and boldness, in confessing God, of the blessed and truly innocent lamb, I refer to the martyr Apphianus, — who presented in the sight of all, before the gates of Caesarea, a wonderful example of piety toward the only God? He was at that time not twenty years old. He had first spent a long time at Berytus, for the sake of a secular Grecian education, as he belonged to a very wealthy family.[2] It is wonderful to relate how, in such a city, he was superior to youthful passions, and clung to virtue, uncorrupted neither by his bodily vigor nor his young companions; living discreetly, soberly and piously, in accordance with his profession of the Christian doctrine and the life of his teachers....

“For in the second attack upon us under Maximinus, in the third year of the persecution, edicts of the tyrant were issued for the first time, commanding that the rulers of the cities should diligently and speedily see to it that all the people offered sacrifices. Throughout the city of Caesarea, by command of the governor, the heralds were summoning men, women, and children to the temples of the idols, and besides this, the chiliarchs were calling out each one by name from a roll, and an immense crowd of the wicked were rushing together from all quarters. Then this youth fearlessly, while no one was aware of his intentions, eluded both us who lived in the house with him and the whole band of soldiers that surrounded the governor, and rushed up to Urbanus as he was offering libations, and fearlessly seizing him by the right hand, straightway put a stop to his sacrificing, and skillfully and persuasively, with a certain divine inspiration, exhorted him to abandon his delusion, because it was not well to forsake the one and only true God, and sacrifice to idols and demons. It is probable that this was done by the youth through a divine power which led him forward, and which all but cried aloud in his act, that Christians, who were truly such, were so far from abandoning the religion of the God of the universe which they had once espoused, that they were not only superior to threats and the punishments which followed, but yet bolder to speak with noble and untrammeled tongue, and, if possible, to summon even their persecutors to turn from their ignorance and acknowledge the only true God.

“Thereupon, he of whom we are speaking, and that instantly, as might have been expected after so bold a deed, was torn by the governor and those who were with him as if by wild beasts. And having endured manfully innumerable blows over his entire body, he was straightway cast into prison. There he was stretched by the tormentor with both his feet in the stocks for a night and a day; and the next day he was brought before the judge. As they endeavored to force him to surrender, he exhibited all constancy under suffering and terrible tortures. His sides were torn, not once, or twice, but many times, to the bones and the very bowels; and he received so many blows on his face and neck that those who for a long time had been well acquainted with him could not recognize his swollen face. But as he would not yield under this treatment, the torturers, as commanded, covered his feet with linen cloths soaked in oil and set them on fire. No word can describe the agonies which the blessed one endured from this. For the fire consumed his flesh and penetrated to his bones, so that the humors of his body were melted and oozed out and dropped down like wax. But as he was not subdued by this, his adversaries being defeated and unable to comprehend his superhuman constancy, cast him again into prison. A third time he was brought before the judge; and having witnessed the same profession, being half dead, he was finally thrown into the depths of the sea.

“But what happened immediately after this will scarcely be believed by those who did not see it. Although we realize this, yet we must record the event, of which to speak plainly, all the inhabitants of Caesarea were witnesses. For truly there was no age but beheld this marvelous sight. For as soon as they had cast this truly sacred and thrice-blessed youth into the fathomless depths of the sea, an uncommon commotion and disturbance agitated the sea and all the shore about it, so that the land and the entire city were shaken by it. And at the same time with this wonderful and sudden perturbation, the sea threw out before the gates of the city the body of the divine martyr, as if unable to endure it. Such was the death of the wonderful Apphianus. It occurred on the second day of the month Xanthicus, which is the fourth day before the Nones of April, on the day of preparation

Martydom and persecution of Christian by the Romans