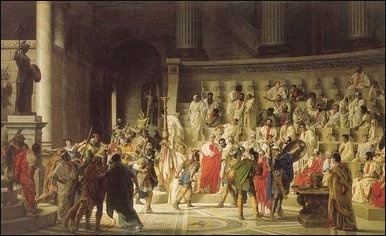

CAESAR’S DICTATORSHIP

Initially Caesar was officially named a dictator for 10 years by the Senate in 46 B.C. In 44 B.C., after defeating his enemies, Caesar declared himself “Dictator for Life” and was crowned with a royal diadem at a religious ceremony, ushering in the era of imperial Rome. Many Romans were appalled by Caesar's audacious seizure of power and riled further when he placed a statue with his likeness next to statues of the founders of Rome. Almost immediately members of the Senate began plotting against him.

As dictator Caesar did some good things such as canceling debt, changing the calendar and currency, and granting citizenship to residents of far regions of the Roman Republic. He abolished the tax system. Instead he exacted tributes from cities. He also started the rebuilding of Carthage, began issuing coins with him on it and stared building a massive temple to Mars as well as a public library. After he was named dictator for life he began consolidating military and political power with plans to expand the borders of Rome. But less than two months later, on the Ides of March in 44 B.C., a mob of Roman senators led by praetor Marcus Junius Brutus stabbed Caesar to death. [Source: National Geographic History, August 24, 2022; Hanna Seariac, Deseret News, April 22, 2023]

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: Caesar “again chose to be named dictator, this time with the complete title of dictator rei publicae constituendae "dictator for the purpose of rebuilding the Republic", which Sulla too had been called, and with a fixed term of ten years. The Republicans were unimpressed by the ten-year limitation, nor willing to deceive themselves about the nature of Caesar's autocratic powers at this stage. And a variety of symbols confirmed Caesar's extraordinary status. For example, in public he was attended after 46 B.C. by 72 lictors (24 for each dictatorship), whereas the standard number for a consul was 12. Although Caesar had refrained from imitating Sulla's violent proscriptions, he was reputed to have opined that Sulla was a fool for having voluntarily stepped down from his dictatorship and retired from public life (Suet. Jul. 77, citing a collection of Caesar's public pronouncements by T. Ampius). [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

In 44 B.C. the dictatorship, for reasons which are not altogether clear, was redefined as perpetual rather than for ten years. Among the evidence which ensures that the perpetual dictatorship is not an invention by hostile sources are the coins. Of course his enemies spread the unlikely rumour that Caesar lusted after the title of king (rex). One is reminded of the stories about how Ti. Gracchus was supposed to have motioned with his hand indicating that he wanted to receive a crown. Crowns were powerful symbols for the Romans. Suetonius says Caesar was annoyed when the tribunes removed a royal crown someone had placed upon his statue, not because he wished to have it there, but because he wished to refuse it himself. The story seems confirmed in as much as it hangs on a matter of public record, that the two tribunes responsible were later deposed; but that may not have been. as Suetonius believes, at Caesar's insistence. M. Antonius tried to crown Caesar himself at the festival of the Lupercalia in 44, as Suetonius also says (Jul. 80); but this was undoubtedly a publicity stunt, designed to make the most of Caesar's public refusal of the dubious honor.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JULIUS CAESAR (102-44 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR’S LIFE AND CHARACTER europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR'S RISE AS A POLITICIAN: CICERO, CATO AND THE CATILINE CONSPIRACY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR'S MILITARY CAREER: SKILLS, LEADERSHIP, VICTORIES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR, POMPEY AND CRASSUS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR, THE CROSSING OF THE RUBICON AND THE SITUATION IN ROME AT THE TIME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CIVIL WAR AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ASSASSINATION OF JULIUS CAESAR europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Julius Caesar: The Life and Times of the People’s Dictator” by Luciano Canfora, Stuart Midgley Marian Hill (2007) Amazon.com;

“Caesar: Politician and Statesman” by Mattias Gelzer, Peter Needham (1968) Amazon.com;

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic” by Tom Holland (2003) Amazon.com

“The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People's History of Ancient Rome” by Michael Parenti Amazon.com;

“Julius Caesar” by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library) Amazon.com;

“The Ides: Caesar's Murder and the War for Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Civil War of Caesar” (Penguin Classics) by Julius Caesar and Jane P. Gardner Amazon.com;

“Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell into Tyranny” by Edward Watts (2020), Illustrated Amazon.com;

“The Fall of the Roman Republic: Roman History, Books 36-40 (Oxford World's Classics)

by Cassius Dio Amazon.com;

“Fall of the Roman Republic (Penguin Classics) by Plutarch Amazon.com;

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“The Lives of the Caesars” (A Penguin Classics Hardcover) by Suetonius, Tom Holland Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Julius Caesar: The Complete Works : Gallic War, Civil War, Alexandrian War, African War, and Spanish War : in One Volume, with Maps, Annotations, Appendices, and Encyclopedic Index” by 2017) Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republics” by Harriet I. Flower (2009) Amazon.com

Caesar Makes Rome into an Empire

Roman empire in Caesar's time Caesar's campaign in Gaul allowed Rome to claim France, the Netherlands and Belgium. In campaigns early in the Civil Wars period he claimed Portugal, Spain, and Greece. With Egypt under the control of Cleopatra, Caesar set his sights on the Middle East.

After annihilating the Parthians in Pontus and Zela in the Middle East in 47 B.C., Caesar sent home the immortal message, " Veni, vidi, vici " ("I came, I saw, I conquered"). This victory allowed him to claim Syria, Israel, and western Turkey. Afterwards he returned home to Rome to fight another rival, Cato, who had gone to North Africa to raise an army to challenge Caesar. That didn't happen. Instead, Caesar sent his army to Africa and crushed Cato.

In 46 B.C., the last of Pompey's forces were defeated in Spain. With the civil wars over Caesar was the unchallenged leader of Rome. In the meantime Portugal, Spain, France, the Netherlands Belgium, Italy, Greece, Syria, Israel, western Turkey, and northern Libya were added to Rome under Caesar, making it a truly great empire. Caesar was merciful enough to forgive his enemies. A general amnesty was proclaimed; and friend and foe were treated alike.

Caesar’s Triumphs and Titles

When Caesar returned to Rome after the battle of Thapsus in Spain, he came not as the servant of the senate, but as master of the world. He crowned his victories by four splendid triumphs, one for Gaul, one for Egypt, one for Pontus, and one for Numidia. He made no reference to the civil war; and no citizens were led among his captives. His victory was attended by no massacres, no proscriptions, no confiscations. He was as generous in peace as he had been relentless in war. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

We may see the kind of power which he exercised by the titles which he received. He was consul, dictator, controller of public morals (praefectus morum), tribune, pontifex maximus, and chief of the senate (princeps senatus). He thus gathered up in his own person the powers which had been scattered among the various republican officers. The name of “imperator” with which the soldiers had been accustomed to salute a victorious general, was now made an official title, and prefixed to his name. In Caesar was thus embodied the one-man power which had been growing up during the civil wars. He was in fact the first Roman emperor.

Suetonius wrote: “Having ended the wars, he celebrated five triumphs, four in a single month, but at intervals of a few days, after vanquishing Scipio; and another on defeating Pompeius' sons. The first and most splendid was the Gallic triumph, the next the Alexandrian, then the Pontic, after that the African, and finally the Hispanic, each differing from the rest in its equipment and display of spoils. As he rode through the Velabrum on the day of his Gallic triumph, the ae of his chariot broke, and he was all but thrown out; and he mounted the Capitol by torchlight, with forty elephants bearing lamps on his right and his left. In his Pontic triumph he displayed among the show-pieces of the procession an inscription of but three words, "I came, I saw, I conquered," [ 'Veni, vidi, vici'] not indicating the events of the war, as the others did, but the speed with which it was finished. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

Spoils for Caesar’s Soldiers

Suetonius wrote: ““To each and every foot-soldier of his veteran legions he gave twenty-four thousand sesterces by way of plunder, over and above the two thousand apiece which he had paid them at the beginning of the civil strife. He also assigned them lands, but not side by side, to avoid dispossessing any of the former owners. To every man of the people, besides ten pecks of grain and the same number of pounds of oil, he distributed the three hundred sesterces which he had promised at first, and one hundred apiece because of the delay. He also remitted a year's rent in Rome to tenants who paid two thousand sesterces or less, and in Italy up to five hundred sesterces. He added a banquet and a dole of meat, and after his Hispanic victory two dinners; for deeming that the former of these had not been served with a liberality creditable to his generosity, he gave another five days later on a most lavish scale. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

“He gave entertainments of divers kinds: a combat of gladiators and also stage-plays in every ward all over the city, performed too by actors of all languages, as well as races in the circus, athletic contests, and a sham sea-fight. In the gladiatorial contest in the Forum Furius Leptinus, a man of praetorian stock, and Quintus Calpenus, a former senator and pleader at the bar, fought to a finish. A Pyrrhic dance was performed by the sons of the princes of Asia and Bithynia. During the plays Decimus Laberius, a Roman eques, acted a farce of his own composition, and having been presented with five hundred thousand sesterces and a gold ring [in token of his restoration to the rank of eques, which he forfeited by appearing on the stage], passed from the stage through the orchestra and took his place in the fourteen rows [the first fourteen rows above the orchestra, reserved for the equites by the law of L. Roscius Otho, tribune of the plebeians, in 67 B.C.].

“For the races the circus was lengthened at either end and a broad canal was dug all about it; then young men of the highest rank drove four-horse and two-horse chariots and rode pairs of horses, vaulting from one to the other. The game called Troy was performed by two troops, of younger and of older boys. Combats with wild beasts were presented on five successive days, and last of all there was a battle between two opposing armies, in which five hundred foot-soldiers, twenty elephants, and thirty horsemen engaged on each side. To make room for this, the goals were taken down and in their place two camps were pitched over against each other. The athletic competitions lasted for three days in a temporary stadium built for the purpose in the region of the Campus Martius. For the naval battle a pool was dug in the lesser Codeta and there was a contest of ships of two, three, and four banks of oars, belonging to the Tyrian and Egyptian fleets, manned by a large force of fighting men. Such a throng flocked to all these shows from every quarter, that many strangers had to lodge in tents pitched in the streets or along the roads, and the press was often such that many were crushed to death, including two senators.”

Caesar’s Accomplishments

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”:“Cæsar was born to do great things, and had a passion after honor, and the many noble exploits he had done did not now serve as an inducement to him to sit still and reap the fruit of his past labors, but were incentives and encouragements to go on, and raised in him ideas of still greater actions, and a desire of new glory, as if the present were all spent. It was in fact a sort of emulous struggle with himself, as it had been with another, how he might outdo his past actions by his future. In pursuit of these thoughts, he resolved to make war upon the Parthians, and when he had subdued them, to pass through Hyrcania; thence to march along by the Caspian Sea to Mount Caucasus, and so on about Pontus, till he came into Scythia; then to overrun all the countries bordering upon Germany, and Germany itself; and so to return through Gaul into Italy, after completing the whole circle of his intended empire, and bounding it on every side by the ocean.

While preparations were making for this expedition, he proposed to dig through the isthmus on which Corinth stands; and appointed Anienus to superintend the work. He had also a design of diverting the Tiber, and carrying it by a deep channel directly from Rome to Circe, and so into the sea near Tarracina, that there might be a safe and easy passage for all merchants who traded to Rome. Besides this, he intended to drain all the marshes by Pomentium and Setia, and gain ground enough from the water to employ many thousands of men in tillage. He proposed further to make great mounds on the shore nearest Rome, to hinder the sea from breaking in upon the land, to clear the coast at Ostia of all the hidden rocks and shoals that made it unsafe for shipping, and to form ports and harbors fit to receive the large number of vessels that would frequent them. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“These things were designed without being carried into effect; but his reformation of the calendar, in order to rectify the irregularity of time, was not only projected with great scientific ingenuity, but was brought to its completion, and proved of very great use. For it was not only in ancient times that the Romans had wanted a certain rule to make the revolutions of their months fall in with the course of the year, so that their festivals and solemn days for sacrifice were removed by little and little, till at last they came to be kept at seasons quite the contrary to what was at first intended, but even at this time the people had no way of computing the solar year; only the priests could say the time, and they, at their pleasure, without giving any notice, slipped in the intercalary month, which they called Mercedonius. Numa was the first who put in this month, but his expedient was but a poor one and quite inadequate to correct all the errors that arose in the returns of the annual cycles, as we have shown in his life. Cæsar called in the best philosophers and mathematicians of his time to settle the point, and out of the systems he had before him, formed a new and more exact method of correcting the calendar, which the Romans use to this day, and seem to succeed better than any nation in avoiding the errors occasioned by the inequality of the cycles. Yet even this gave offence to those who looked with an evil eye on his position, and felt oppressed by his power. Cicero, the orator, when some one in his company chanced to say, the next morning Lyra would rise, replied, “Yes, in accordance with the edict,” as if even this were a matter of compulsion.

“But that which brought upon him the most apparent and mortal hatred, was his desire of being king; which gave the common people the first occasion to quarrel with him, and proved the most specious pretence to those who had been his secret enemies all along. Those, who would have procured him that title, gave it out, that it was foretold in the Sybils’ books that the Romans should conquer the Parthians when they fought against them under the conduct of a king, but not before. And one day, as Cæsar was coming down from Alba to Rome, some were so bold as to salute him by the name of king; but he finding the people disrelish it, seemed to resent it himself, and said his name was Cæsar, not king. Upon this, there was a general silence, and he passed on looking not very well pleased or contented. Another time, when the senate had conferred on him some extravagant honors, he chanced to receive the message as he was sitting on the rostra, where, though the consuls and prætors themselves waited on him, attended by the whole body of the senate, he did not rise, but behaved himself to them as if they had been private men, and told them his honors wanted rather to be retrenched than increased.

This treatment offended not only the senate, but the commonalty too, as if they thought the affront upon the senate equally reflected upon the whole republic; so that all who could decently leave him went off, looking much discomposed. Cæsar, perceiving the false step he had made, immediately retired home; and laying his throat bare, told his friends that he was ready to offer this to any one who would give the stroke. But afterwards he made the malady from which he suffered, the excuse for his sitting, saying that those who are attacked by it, lose their presence of mind, if they talk much standing; that they presently grow giddy, fall into convulsions, and quite lose their reason. But this was not the reality, for he would willingly have stood up to the senate, had not Cornelius Balbus, one of his friends, or rather flatterers, hindered him. “Will you not remember,” said he, “you are Cæsar, and claim the honor which is due to your merit?”

“He gave a fresh occasion of resentment by his affront to the tribunes. The Lupercalia were then celebrated, a feast at the first institution belonging, as some writers say, to the shepherds, and having some connection with the Arcadian Lycæa. Many young noblemen and magistrates run up and down the city with their upper garments off, striking all they meet with thongs of hide, by way of sport; and many women, even of the highest rank, place themselves in the way, and hold out their hands to the lash, as boys in a school do to the master, out of a belief that it procures an easy labor to those who are with child, and makes those conceive who are barren. Cæsar, dressed in a triumphal robe, seated himself in a golden chair at the rostra, to view this ceremony. Antony, as consul, was one of those who ran this course, and when he came into the forum, and the people made way for him, he went up and reached to Cæsar a diadem wreathed with laurel. Upon this, there was a shout, but only a slight one, made by the few who were planted there for that purpose; but when Cæsar refused it, there was universal applause. Upon the second offer, very few, and upon the second refusal, all again applauded. Cæsar finding it would not take, rose up, and ordered the crown to be carried into the capitol. Cæsar’s statues were afterwards found with royal diadems on their heads. Flavius and Marullus, two tribunes of the people, went presently and pulled them off, and having apprehended those who first saluted Cæsar as king, committed them to prison. The people followed them with acclamations, and called them by the name of Brutus, because Brutus was the first who ended the succession of kings, and transferred the power which before was lodged in one man into the hands of the senate and people. Cæsar so far resented this, that he displaced Marullus and Flavius; and in urging his charges against them, at the same time ridiculed the people, by himself giving the men more than once the names of Bruti, and Cumæi.

Caesar’s Reforms

Caesar held his great power only for a short time. But the reforms which he made are enough to show us his policy, and to enable us to judge of him as a statesman. Fernando Lillo Redonet wrote in National Geographic History magazine: “Having returned to Rome, he continued implementing significant reforms in the year of life left to him. These included improving land and grain distribution, as well as the reorganization of local government across Italy. No doubt Caesar hoped for many years of life to enact his reforms.” [Source: Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History magazine, March-April 2017]

Suetonius wrote: “Then turning his attention to the reorganisation of the state, he reformed the calendar, which the negligence of the pontiffs had long since so disordered, through their privilege of adding months or days at pleasure, that the harvest festivals did not come in summer nor those of the vintage in the autumn; and he adjusted the year to the sun's course by making it consist of three hundred and sixty-five days, abolishing the intercalary month, and adding one day every fourth year [the year had previously consisted of 355 days, and the deficiency of about eleven days was made up by inserting an intercalary month of twenty-two or twenty-three days after February]. Furthermore, that the correct reckoning of seasons might begin with the next Kalends of January, he inserted two other months between those of November and December; hence the year in which these arrangements were made was one of fifteen months, including the intercalary month, which belonged to that year according to the former custom. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

“Moreover, to keep up the population of the city, depleted as it was by the assignment of eighty thousand citizens to colonies across the sea, he made a law that no citizen older than twenty or younger than forty, who was not detained by service in the army, should be absent from Italia for more than three successive years; that no senator's son should go abroad except as the companion of a magistrate or on his staff; and that those who made a business of grazing should have among their herdsmen at least one-third who were men of free birth. He conferred citizenship on all who practiced medicine at Rome, and on all teachers of the liberal arts, to make them more desirous of living in the city and to induce others to resort to it. As to debts, he disappointed those who looked for their cancellation, which was often agitated, but finally decreed that the debtors should satisfy their creditors according to a valuation of their possessions at the price which they had paid for them before the civil war, deducting from the principal whatever interest had been paid in cash or pledged through bankers; an arrangement which wiped out about a fourth part of their indebtedness. He dissolved all colleg [associations], except those of ancient foundation. He increased the penalties for crimes; and inasmuch as the rich involved themselves in guilt with less hesitation because they merely suffered exile, without any loss of property, he punished murderers of freemen by the confiscation of all their goods, as Cicero writes, and others by the loss of one-half.

“He administered justice with the utmost conscientiousness and strictness. Those convicted of extortion he even dismissed from the senatorial order. He annulled the marriage of an ex-praetor, who had married a woman the very day after her divorce, although there was no suspicion of adultery. He imposed duties on foreign wares. He denied the use of litters and the wearing of scarlet robes or pearls to all except to those of a designated position and age, and on set days. In particular, he enforced the law against extravagance, setting watchmen in various parts of the market, to seize and bring to him dainties which were exposed for sale in violation of the law; and sometimes he sent his lictors and soldiers to take from a dining-room any articles which had escaped the vigilance of his watchmen, even after they had been served.

“In particular, for the adornment and convenience of the city, also for the protection and extension of the Empire, he formed more projects and more extensive ones every day; first of all, to rear a temple to Mars, greater than any in existence, filling up and levelling the pool in which he had exhibited the sea-fight, and to build a theater of vast size, sloping down from the Tarpeian Rock; to reduce the civil code to fixed limites, and of the vast and prolix mass of statutes to include only the best and most essential in a limited number of volumes; to open to the public the greatest possible libraries of Greek and Latin books, assigning to Marcus Varro the charge of procuring and classifying them; to drain the Pomptine marshes; to let out the water from Lake Fucinus; to make a highway from the Adriatic across the summit of the Apennines as far as the Tiber; to cut a canal through the Isthmus; to check the Dacians, who had poured into Pontus and Thrace; then to make war on the Parthians by way of Lesser Armenia, but not to risk a battle with them until he had first tested their mettle. All these enterprises and plans were cut short by his death. But before I speak of that, it will not be amiss to describe briefly his personal appearance, his dress, his mode of life, and his character, as well as his conduct in civil and military life.

Caesar’s Political Reforms

Roman Senate

The first need of Rome was a stable government based on the interest of the whole people. The senate had failed to secure such a government; and so had the popular assemblies led by the tribunes. Caesar believed that the only government suited to Rome was a democratic monarchy—a government in which the supreme power should be held permanently by a single man, and exercised, not for the benefit of himself or any single class, but for the benefit of the whole state. Let us see how his changes accomplished this end. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

In the first place, the senate was changed to meet this view. It had hitherto been a comparatively small body, drawn from a single class and ruling for its own interests. Caesar increased the number to nine hundred members, and filled it up with representative men of all classes, not simply nobles, but also ignobiles—Spaniards, Gauls, military officers, sons of freedmen, and others. It was to be not a legislative body but an advisory body, to inform the monarch of the condition and wants of Italy and the provinces. In the next place, he extended the Roman franchise to the inhabitants beyond the Po, and to many cities in the provinces, especially in Transalpine Gaul and Spain. All his political changes tended to break down the distinction between nobles and commons, between Italians and the provincials, and to make of all the people of the empire one nation. \~\

Suetonius wrote: ““He filled the vacancies in the senate, enrolled additional patricians, and increased the number of praetors, aediles, and quaestors, as well as of the minor officials; he reinstated those who had been degraded by official action of the censors or found guilty of bribery by verdict of the jurors. He shared the elections with the people on this basis: that except in the case of the consulship, half of the magistrates should be appointed by the people's choice, while the rest should be those whom he had personally nominated. And these he announced in brief notes like the following, circulated in each tribe: 'Caesar the Dictator to this or that tribe. I commend to you so and so, to hold their positions by your votes." He admitted to office even the sons of those who had been proscribed. He limited the right of serving as jurors to two classes, the equestrian and senatorial orders, disqualifying the third class, the tribunes of the treasury. He made the enumeration of the people neither in the usual manner nor place, but from street to street aided by the owners of blocks of houses, and reduced the number of those who received grain at public expense from three hundred and twenty thousand to one hundred and fifty thousand. And to prevent the calling of additional meetings at any future time for purposes of enrolment, he provided that the places of such as died should be filled each year by the praetors from those who were not on the list. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

Caesar’s Economic Reforms

Caesar coin

The next great need of Rome was the improvement of the condition of the lower classes. Caesar well knew that the condition of the people could not be changed in a day; but he believed that the government ought not to encourage pauperism by helping those who ought to help themselves. There were three hundred and twenty thousand persons at Rome to whom grain was distributed. He reduced this number to one hundred and fifty thousand, or more than one half. He provided means of employment for the idle, by constructing new buildings in the city, and other public works; and also by enforcing the law that one third of the labor employed on landed estates should be free labor. As the land of Italy was so completely occupied, he encouraged the establishment, in the provinces, of agricultural colonies which would not only tend to relieve the farmer class, but to Romanize the empire. He relieved the debtor class by a bankrupt law which permitted the insolvent debtor to escape imprisonment by turning over his property to his creditors. In such ways as these, while not pretending to abolish poverty, he afforded better means for the poorer classes to obtain a living. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

His Reform of the Provincial System: The despotism of the Roman republic was nowhere more severe and unjust than in the provinces. This was due to two things—the arbitrary authority of the governor, and the wretched system of farming the taxes. The governor ruled the province, not for the benefit of the provincials, but for the benefit of himself. It is said that the proconsul hoped to make three fortunes out of his province—one to pay his debts, one to bribe the jury if he were brought to trial, and one to keep himself. The tax collector also looked upon the property of the province as a harvest to be divided between the Roman treasury and himself. Caesar put a check upon this system of robbery. The governor was now made a responsible agent of the emperor; and the collection of taxes was placed under a more rigid supervision. The provincials found in Caesar a protector; because his policy involved the welfare of all his subjects. \~\

His Other Reforms and Projects: The most noted of Caesar’s other changes was the reform of the calendar, which has remained as he left it, with slight change, down to the present day. He also intended to codify the Roman law; to provide for the founding of public libraries; to improve the architecture of the city; to drain the Pontine Marshes for the improvement of the public health; to cut a channel through the Isthmus of Corinth; and to extend the empire to its natural limits, the Euphrates, the Danube, and the Rhine. These projects show the comprehensive mind of Caesar. That they would have been carried out in great part, if he had lived, we can scarcely doubt, when we consider his wonderful executive genius and the works he actually accomplished in the short time in which he held his power. \~\

Caesar’ Vanity and High Living

Suetonius wrote: ““He is said to have been tall of stature, with a fair complexion, shapely limbs, a somewhat full face, and keen black eyes; sound of health, except that towards the end he was subject to sudden fainting fits and to nightmare as well. He was twice attacked by the falling sickness [morbus comitialis, so-called because an attack was considered sufficient cause for the postponement of elections, or other public business. This is thought to have been epilepsy.] during his campaigns. He was somewhat overnice in the care of his person, being not only carefully trimmed and shaved, but even having superfluous hair plucked out, as some have charged; while his baldness was a disfigurement which troubled him greatly, since he found that it was often the subject of the gibes of his detractors. Because of it he used to comb forward his scanty locks from the crown of his head, and of all the honors voted him by the senate and people there was none which he received or made use of more gladly than the privilege of wearing a laurel wreath at all times. They say, too, that he was remarkable in his dress; that he wore a senator's tunic [Latus clavus, the broad purple stripe, is also applied to a tunic with the broad stripe. All senators had the right to wear this; the peculiarity in Caesar's case consisted in the long fringed sleeve.] with fringed sleeves reaching to the wrist, and always had a girdle [While a girdle was commonly worn with the ordinary tunic, it was not usual to wear one with the latus clavus.] over it, though rather a loose one; and this, they say, was the occasion of Sulla's mot, when he often warned the nobles to keep an eye on the ill-girt boy. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

Suetonius wrote: “He lived at first in the Subura in a modest house, but after he became pontifex maximus, in the official residence on the Sacred Way. Many have written that he was very fond of elegance and luxury; that having laid the foundations of a countryhouse on his estate at Nemi and finished it at great cost, he tore it all down because it did not suit him in every particular, although at the time he was still poor and heavily in debt; and that he carried tesselated and mosaic floors about with him on his campaigns. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

“They say that he was led to invade Britannia by the hope of getting pearls, and that in comparing their size he sometimes weighed them with his own hand; that he was always a most enthusiastic collector of gems, carvings, statues, and pictures by early artists; also of slaves of exceptional figure and training at enormous prices, of which he himself was so ashamed that he forbade their entry in his accounts. It is further reported that in the provinces he gave banquets constantly in two dining halls, in one of which his officers or Greek companions, in the other Roman civilians and the more distinguished of the provincials reclined at table. He was so punctilious and strict in the management of his household, in small matters as well as in those of greater importance, that he put his baker in irons for serving him with one kind of bread and his guests with another; and he inflicted capital punishment on a favorite freedman for adultery with the wife of a Roman eques, although no complaint was made against him.”

Caesar Worship

Caesar's deification

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Some moderns do accept that Caesar in his last years encouraged the worship of himself as a god at Rome (following Dio 44.6.5-6, Appian BC 2.106); but this may be a distortion of the indisputable fact that a temple had been erected to clemency or to his clemency. Naturally, being acclaimed as a god by the people of the east (as Caesar was) was seen at Rome as matter of small import. It is true that the Senate declared Caesar to have been a god upon his death, and the popular belief was that a comet seen shortly after his assassination marked his assumption into the heavenly realm (a tale lovingly fostered by Augustus). In short, although there are some distortions, even the most ardent defenders of Caesar must admit that at the end he seems to have become drunk with power and the endless stream of honors heaped upon him by the Senate, and that he ended by making a mockery of Republican practices. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class]

Suetonius wrote: “To an insult which so plainly showed his contempt for the Senate he added an act of even greater insolence; for at the Latin Festival, as he was returning to the city, amid the extravagant and unprecedented demonstrations of the populace, someone in the press placed on his statue a laurel wreath with a white fillet tied to it [an emblem of royalty]; and when Epidius Marullus and Caesetius Flavus, tribunes of the plebeians, gave orders that the ribbon be removed from the wreath and the man taken off to prison, Caesar sharply rebuked and deposed them, either offended that the hint at regal power had been received with so little favor, or, as he asserted, that he had been robbed of the glory of refusing it. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

“But from that time on he could not rid himself of the odium of having aspired to the title of monarch, although he replied to the plebeians, when they hailed him as king, "I am Caesar and no king" [with a pun on rex ('king') as a Roman name], and at the Lupercalia, when the consul Marcus Antonius several times attempted to place a crown upon his head as he spoke from the rostra, he put it aside and at last sent it to the Capitol, to be offered to Jupiter Optimus Maximus. Nay, more, the report had spread in various quarters that he intended to move to Ilium or Alexandria, taking with him the resources of the state, draining Italia by levies, and leaving the charge of the city to his friends; also that at the next meeting of the Senate Lucius Cotta would announce as the decision of the Fifteen [the quindecimviri sacris faciundis ('college of fifteen priests') in charge of the Sybilline books], that inasmuch as it was written in the books of fate that the Parthians could be conquered only by a king, Caesar should be given that title.”

Cicero’s Concerns About Caesar

The great orator and politician Cicero (106-43 B.C.) raised concerns about Caesar’s rise in Letter XXX: To Atticus (at Rome) Matius' Suburban Villa, 7 April, 44 B.C: “I have come on a visit to the man, of whom I was talking to you this morning. His view is that "the state of things is perfectly shocking: that there is no way out of the imbroglio. For if a man of Caesar's genius failed, who can hope to succeed?" In short, he says that the ruin is complete. I am not sure that he is wrong; but then he rejoices in it, and declares that within twenty days there will be a rising in Gaul: that he has not had any conversation with anyone except Lepidus since the Ides of March: finally that these things can't pass off like this. [Source: Cicero, Marcus Tullius: “The Letters of Cicero”, translated by Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (d. 1906), London, G. Bell and sons, 1899-1900]

What a wise man Oppius is, who regrets Caesar quite as much, but yet says nothing that can offend any loyalist! But enough of this. Pray don't be idle about writing me word of anything new, for I expect a great deal. Among other things, whether we can rely on Sextus Pompeius; but above all about our friend Brutus, of whom my host says that Caesar was in the habit of remarking: "It is of great importance what that man wishes; at any rate, whatever he wishes he wishes strongly": and that he noticed, when he was pleading for Deiotarus at Nicaea, that he seemed to speak with great spirit and freedom.

Casear by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

“Also - for I like to jot down things as they occur to me - that when on the request of Sestius I went to Caesar's house, and was sitting waiting till I was called in, he remarked: "Can I doubt that I am exceedingly disliked, when Marcus Cicero has to sit waiting and cannot see me at his own convenience? And yet if there is a good-natured man in the world it is he; still I feel no doubt that he heartily dislikes me." This and a good deal of the same sort. But to my purpose: Whatever the news, small as well as great, write and tell me of it. I will on my side let nothing pass.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024