EDUCATION IN ANCIENT GREECE

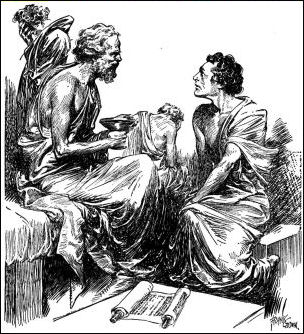

Socrates teaching For the most part, upper class youths were the only Greek children who received an education. Teachers, in most cases, were either educated slaves or tutors hired out for a fee. Most children began their studies at age seven. but there were no strict rules governing when a child's schooling began or how long it should last.

In the 7th and 6th century B.C. education was thought of as preparation for war and membership in the upper classes. Sports and athletic were taught to prepare boys for war and music and dance was learned by both boys and girls for acceptance among the elite. In the 5th century B.C. the Athenians developed schools that were not all that much different from those today. Younger students were taught reading, writing and arithmetic and older students studied philosophy, rhetoric and geometry. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

Generally speaking, we may say that the main object of the education of the youths in the best period of Greek antiquity was to train a citizen, capable in body and mind, who should be able to serve his country as well in war as in peace, in a public as in a private capacity, while all special development of any branch of learning, except, of course, the gymnastic element, was excluded. There was a marked distinction between the Doric states (including Athens) and Ionic states (including Sparta). In the latter the education of boys was a private duty of the parents, and the State only retained a general right of control; while in the Doric states, and especially at Sparta, with whose institutions we are best acquainted, boys were regarded as belonging, not to the family, but to the State, which undertook the entire charge of their physical and intellectual well-being. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The father decided how the child would be raised and educated, some favoring home schooling and others bringing in tutors to educate them. (Alexander, the Great's father King Philip brought in Aristotle to serve as teacher and mentor to the young Alexander.)A typical upper class education included instruction in poetry, music, oratory and gymnastics. The emphasis was more on the spoken word than the written word. At the gymnasiums, men taught boys about their duties to the community, proper behavior and how to carry oneself as a man.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SCHOOLS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TEACHING IN ANCIENT GREECE: INSTRUCTION, TEACHERS, METHODS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CURRICULUM AND SUBJECTS TAUGHT IN ANCIENT GREEK SCHOOLS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Greek and Roman Education” by Robin Barrow (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World” by Judith Evans Grubbs and Tim Parkin (2013) Amazon.com;

“Children in Antiquity: Perspectives and Experiences of Childhood in the Ancient Mediterranean” by Lesley A. Beaumont, Matthew Dillon, et al. (2024)

“A History Of Education In Antiquity” by H.I. Marrou and George Lamb (1982) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Education: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Mark Joyal , J.C Yardley, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Gymnasium of Virtue: Education & Culture in Ancient Sparta” by Nigel M. Kennell (1995) Amazon.com;

“Gymnastics of the Mind: Greek Education in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt”

by Raffaella Cribiore (2005) Amazon.com;

“Plato's Academy Annotated Edition” by Paul Kalligas Amazon.com;

“Rhetoric to Alexander” (Illustrated) by Aristotle and Aeterna Press (2015), of dubious origin Amazon.com;

“Libraries in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“School in Ancient Greece” by Dimitris Pandermalis (2024) Amazon.com;

“Writing Greek: An Introduction to Writing in the Language of Classical Athens”

by John Taylor and Stephen Anderson (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mathematics: History of Mathematics in Ancient Greece and Hellenism”

by Dietmar Herrmann (2023) Amazon.com;

“Mathematics in Ancient Greece (Dover Books) by Tobias Dantzig (2012) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Athens: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2019) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins (1986) Amazon.com;

“Greek Realities: Life and Thought in Ancient Greece” by Finley P. Hooper (1978) Amazon.com;

“The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” (Classic Reprint) by Alice Zimmern (1855-1939) Amazon.com;

“The Life of the Ancient Greeks, With Special Reference to Athens”

by Charles Burton (1868-1962) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

World’s First University in Alexandria?

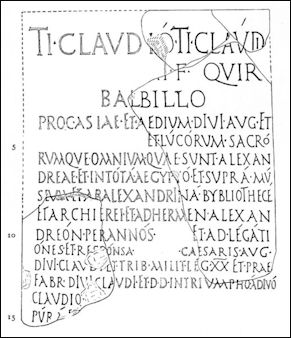

Alexandria Library Inscription Before the library was built in Alexandria, Ptolemy I founded the Mouseion, a research institute which some regard as the world’s first university. It had lecture halls, laboratories and guest rooms for visiting scholars. Archimedes, Aruistarchus of Samos and Euclid all worked there. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Smithsonian magazine, April 2007]

Excavations in downtown Alexandria in the 1990s and 2000s revealed lecture halls from the Mouseion. The area that has been reconstructed thus far shows a row of rectangular halls. Each has a a separate entrance into the street and horse-shoe-shaped stone bleachers. The neat rows of rooms lie in a portico between the Greek theater and the Roman baths. The facilities were built about A.D. 500.

Grzegorz Majcherek. A Polish archaeologist from Warsaw University who is working the site, told Smithsonian magazine, he believes the rooms and hall “were used for higher education — and the level of education was very high.” Texts in other archives show that professors were well paid with public funds and they were forbidden from teaching private lessons except on their days off. There is also evidence that both Christian and pagan scholars worked there.”

Perhaps similar institutions existed in Antioch, Constantinople, Beirut or Rome but no evidence of them has turned up. Majcherek believes Mouseion may have attracted many scholars from the Athens Academy, which closed in A.D. 529. There is some evidence that intellectual activity continued after the arrival of Islam in the 7th century but things later quieted down and likely shifted to Damascus or Baghdad.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ALEXANDRIA: ITS HISTORY, LIBRARY AND LIGHTHOUSE europe.factsanddetails.com

Education for Wealthy Athens Children

The father also decided how the child would be raised and educated, some favoring home schooling and others bringing in tutors to educate them. (Alexander, the Great's father King Philip brought in Aristotle to serve as teacher and mentor to the young Alexander.) Children grew up playing with a variety of toys ( rattles, balls, miniature chariots, wooden boats, clay houses; animal figures- pigs, goats, etc.) as well as perhaps a small number of pets- dogs, ducks, mice and, even, insects. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

Formal education covered the usual 3 R's ( reading, w riting and a rithmetic) as well as physical education and music. For the ancient Greeks, music was considered to have great importance in a proper education curriculum and students learned both to sing and to play various instruments. The school master and the music teacher conducted lessons in their own homes, not in state constructed schools. Although the state valued and took an interest in education, carrying out the instruction was a matter of private initiative. The works of Homer were an important part of the course of studies serving an a source of inspiration for lessons dealing with matters of a moral or religious nature. Homer was perceived as a guide for a proper life while the writings of Hesiod and Solon were considered of secondary importance. |

“By the age of eighteen the young Athenian was ready for military service. Prior to this, from roughly the age of twelve, he would have had considerable exposure to physical training participating in a range of activities- running, wrestling, jumping, discus and javelin. Of course many of the skills learned in these sporting endeavors would prove to be useful in time of war.” |

Education for Spartan Children

Every Spartan citizen could, in a measure, exercise paternal rights over every boy, and, again, was regarded by every boy in the same light as his own father. Obedience towards their elders, modest and reverent bearing, were impressed on the Spartan boys from their earliest years, and they were thus advantageously distinguished from the somewhat precocious Attic youth. The aim of their whole education was to harden the body and to attain the greatest possible bodily skill. The boys had only the most necessary clothing; from their twelfth year onwards they wore only an upper garment, even in winter, and in all other respects their life was of the simplest, so that it is not a mere figure of speech to talk of Spartan discipline. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The instruction at Sparta also corresponded to these principles. There was little question of developing the intellect, nor was this part of the public duty, but only a private matter. Those who wished to learn reading and writing doubtless found an opportunity of doing so, but not in the institutes conducted by the State; at any rate, we find no mention of such. Probably most Spartans did learn so much, but very little more. A little arithmetic was added, as mental arithmetic especially was regarded as important on account of its practical utility. But this was all the literary culture which a young Spartan received.

The Spartan student curriculum developed only basic skills in reading and writing. The emphasis was on content that would be useful in a military career- survival training, how to endure hardship, overcome obstacles and fend for yourself in hostile territory. Spartan youth went barefoot, they wore a single cloak in all kinds of weather and they were fed sparingly. They were encouraged to supplement their rations by stealing food and then whipped if they were caught in the process. The whip, in fact, played an important role in their upbringing. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

By twenty, the Spartan youth had reached adulthood. At this stage he joined a “dining group” of his military peers. He ate all his meals with that group, bonding and developing a sense of camaraderie essential for hoplite warfare where all relied on each other. Sometime in the course of the next decade he would marry and live, not at home, but with his military messmates until he had reached the age of thirty. |

Spartan girls enjoyed more freedom than their Greek counterparts in other states. They were educated by the state and their primary mission was to have children, particularly young soldiers-in-waiting. To that end they were well-nourished and encouraged to exercise, participating in a range of sports activities. Spartan women were also allowed to inherit and own property.” |

See Separate Article: SPARTAN MILITARY, TRAINING AND SOLDIER CITIZENS europe.factsanddetails.com

Education of Girls in Ancient Greece

There is far less to be said about the education of girls, since no regular instruction was given. The sphere to which women were confined in all the Greek states was the household, and their position, especially in the Ionic states, was so distinctly a subordinate one that it was not considered desirable to give them also regular teaching. In consequence there were no girls’ schools; girls belonging to the better classes were taught a little reading and writing by their mothers or nurses — the women of the lower classes did not learn even this — and, with the addition of some superficial knowledge of religion and mythology, such as could be acquired from stories or by reading the poets, this constituted all the intellectual development which fell to the lot of the girls. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Sometimes a little musical instruction was also given, and even in the Ionic states there were some exceptions, since we hear of women of higher intellectual development. As a rule, it was only the hetaerae, whose freer intercourse with men enabled them to gain from them more extensive literary culture; and as a consequence we find that even men of high intellectual powers chose to associate with these persons, and that at Athens, at any rate, the men who desired the stimulus of intercourse with intellectual women, were bound to seek it from this class. The fault was, of course, their own, since the semi-Asian system of shutting off women from the outer world and degrading them into mere managers of the household, necessarily lowered the average culture of women. Still, it sometimes happened that a man who had married a young open-minded girl contrived to raise her up intellectually to himself, and to develop her powers, as Xenophon has shown in his Oikonomikos.

On the other hand, Greek women appear to have been experienced in feminine arts — such as spinning and weaving, sewing and embroidery, accomplishments which they certainly learnt from their mothers and nurses. No regular instruction was given in them, or in cooking, an art with which Greek women were undoubtedly well acquainted. This system of educating girls did not, however, meet with general approval, for we find that Plato, in his “Laws,” prescribes regular school instruction for girls in the subjects required for women, and also musical and even athletic training. These principles were, however, never practically realised at Athens, though elsewhere the conditions may have been different, since an inscription from Teos of somewhat late date makes express mention of instruction given in common to boys and girls.

It was a natural consequence of the very different position occupied by women at Athens and Sparta, that the latter had a very different education from the Athenian women. Though the young Spartan maidens did not, like the boys, associate together in clubs, but remained with their families, yet the State took cognisance of these also, and especially prescribed for them athletic training, which was in essentials the same as that given to the boys, though with corresponding modifications, in order to develop and strengthen their bodies. Of course, they had their own special schools for this purpose, distinct from those of the boys, where they were instructed in running, jumping, wrestling, throwing the spear and discus, as well as in several exercises in running and springing, which were partly of a military character, partly allied with dancing. For this purpose they wore a special dress; One image shows us a female racer from Elis. The statue which is in the Vatican is in the ancient style, and represents a robust girl clad in a short chiton, with a girdle descending only a little way below the hips, and leaving the right breast exposed. This special dress used for athletic exercises must not, however, be confused with that in which the Spartan ladies usually appeared, though this, too, as already stated, differed from the ordinary dress of Greek girls. In spite, however, of this dress, and of the fact that youths and maidens, who in the Ionic states scarcely ever met each other except at religious festivals, were brought into frequent contact at Sparta, especially at public contests, games, choruses, etc., the Spartan women bore an unstained reputation. The system of physical exercises produced healthy women, strongly built, with blooming complexions; and it also implanted and developed in them the manly and determined spirit for which the Laconian women and mothers were distinguished. Yet, even at Sparta, there was no question of intellectual training for the girls; and, indeed, as we have already seen, even in the case of the boys, it was regarded as far less important than physical education.

Ephebeia — Boys Education from 16 to 20

Such was the training given to the boys until about their sixteenth year. This was, however, by no means the end of their education, at any rate not for boys of the better classes, who were not obliged to follow any definite profession; and the athletic training extended for several years longer. The years between adolescence and somewhere about the twentieth year were generally called ephebeia; but besides this expression we find a good many others, especially in inscriptions, which prove that there were several sub-divisions for the purposes of athletic exercises and tests, made according to age; in fact, they generally distinguished between a first, second, and third class of ephebi. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

But there were other special names in use. In ancient times the only distinction in the gymnastic tests was between boys and men, and the ephebi were therefore included in the former class; but afterwards they distinguished between boys, youths, and men, though these designations and their sub-divisions according to age seem to have varied a good deal according to time and place. In any case, we must distinguish between the use of the term ephebus in the gymnastic classes and in the State. For State purposes it was not applied till the eighteenth or nineteenth year, and the boy had then to take his oath as a citizen; his name was entered in the book of his deme, and he received a warrior’s shield and spear. The oath taken by the ephebi, composed by Solon, has been preserved to us. The youth had to swear “Never to disgrace his holy arms, never to forsake his comrade in the ranks, but to fight for the holy temples and the common welfare, alone or with others; to leave his country, not in a worse, but in a better state than he found it; to obey the magistrates and the laws, and defend them against attack; finally to hold in honor the religion of his country.” The witnesses to this oath were, besides Zeus, a number of special Attic local deities of military or agrarian importance.

When a boy attained to the condition of ephebus he discarded the himation and adopted the chlamys as his characteristic dress. The hair, which was worn long by boys, was cut short, and this act of cutting the hair was a kind of religious ceremony, since the hair cut off was often dedicated to some deity. This sacred rite, the importance of which we can better understand if we imagine our modern rite of Confirmation combined with the attainment of majority, was usually celebrated as a festival in the family circle. The new ephebi, after taking their oath and receiving their arms, were presented publicly to the people in the Theatre. This usually took place at the festival of Dionysus, immediately before the performance of a tragedy. It is, however, not quite certain whether this introduction was confined to the sons of those only who had fallen in battle, whose equipment was presented to them by the State. This, however, like most of the details which we have about the ephebeia in Ancient Greece, refers specially to Athens; at Sparta and other places there were customs, more or less different, of which we know little or nothing. Moreover, at Athens, as well as in the rest of Greece and Asia Minor, the usage concerning the ephebi underwent many changes during the Hellenistic period and the Roman Empire. The numerous inscriptions give us far more exact details of this later period than of the best time; but we refrain from discussing them, since this institution, which originally had an essentially warlike character, gradually became a mere matter of form, and was confined to the sons of rich citizens, who merely played with the customs without regarding their ethical or political importance. Most of the information which the inscriptions supply about the officers and teachers of the ephebi also belongs to the later period; a great many boards of management for the arrangements concerning the ephebi, which became more and more complicated, were either created fresh or transformed out of the older ones, but their importance and powers were entirely different. Moreover, our purpose is to confine our attention to the classical and Hellenistic period.

Physical Training for Ephebi

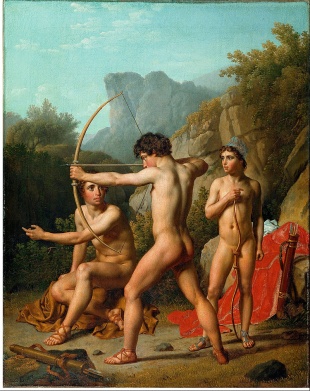

As for the subjects of gymnastic instruction, these were in part the same as those in which the boys had already been trained in the gymnastic school, but gradually becoming more difficult, while others were added to them which were usually excluded from the wrestling school — namely, boxing, pancratium, and pentathlum. Besides these there was fencing with heavy weapons; the fencing was not properly connected with the exercises of the gymnastic tests, but it formed an important part of the military education of the ephebi, and was the more important for these because, when they attained their majority as citizens, they had to spend several years in a kind of garrison and frontier service. This was a training for military service which the ephebi, like all other citizens capable of bearing arms, had to perform from their twentieth year upwards, and they generally served the State for two years before in the manner above mentioned. Methodical instruction in fencing was originally rather looked down upon, but still was accepted in the curriculum of the ephebi, and in the inscriptions the fencing-master has a regular place beside the other masters. Plato also recommends fencing as strengthening for the body and useful in case of war, but he warns people to avoid all display and professionalism. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

In the course of time other exercises in arms were added. Throwing the spear was part of the regular athletic training practised even by boys; and in many inscriptions of the last three centuries B.C. mention is made of special teachers. Shooting with bow and arrows was also learnt, and a teacher for this is mentioned in these inscriptions, as well as one who gave instruction in hurling and in the use of machines for throwing. Probably these purely military exercises were not part of the regular gymnastic curriculum. The same may be said of riding. Every youth had to learn riding, for he had to perform his frontier service on horseback; and at the great festivals, especially the Panathenaea, the troops of ephebi on horseback formed one of the most conspicuous parts of the procession, and, indeed, they occupy the greater part of the relief on the Parthenon frieze. One image, taken from a vase painting, represents ephebi racing on horseback; on the left stands a column, no doubt marking the limit of the course. In fact, representations on vase paintings of ephebi on horseback are very common. Still we cannot assume that regular methodical instruction in riding was given in the older period, at any rate not as part of the instruction of youths, though even in the time of Plato there were riding-masters who seem to have understood how to deal with difficult horses. At a later period the president seems to have occupied himself with instruction in riding, but we know no details about this. The Greeks used neither horse-shoes nor stirrups, therefore, unless some stone for mounting happened to be at hand, they had to jump on to their horses, and this they usually did with the help of their lances; saddles were also unknown, but horse-cloths were generally used, and though on the Parthenon frieze and the vase pictures we see the ephebi riding without these, we must regard this as an artistic license, like the absence of the chiton on the same pictures. To ride thus in a procession, clad merely in the chlamys, without any under garment, on a horse without a saddle, would appear a very doubtful pleasure even to the most hardened Athenian youths.

As regards the other exercises not directly included in exercises, we may state that swimming was practised from earliest youth, and was regarded as indispensable for everyone, so that it was proverbially said of an absolutely uneducated person that he could neither swim nor say his alphabet. The most celebrated swimmers were the inhabitants of the island of Delos, but the Athenians were also distinguished. There were no special swimming masters; children learnt to swim by themselves or were instructed by their fathers.

Inscriptions also tell us that the Attic ephebi every year made expeditions by sea from the Peiraeus to the harbour of Munychia, and in later times also to Salamis, and these apparently partook of the nature of a regatta. Connected with these, even in the Hellenistic period, were naval contests, so that at that time the ephebi must have had some knowledge of the elements of seafaring, unless these sea-fights bore the character of naval games, and were conducted rather for amusement than for serious military purposes; and this is the more probable as at that period, when Athens had long ago lost its political importance, actual preparations for naval warfare had no special aim for young Athenians.

Finally there were, even in the earlier centuries, exercises in marching in the neighbouring country. These were partly connected with the military position of the ephebi as protectors of the frontier, and they partly aimed at extending their knowledge of localities as well as giving practice in marching and riding. As they sometimes had to march out in heavy armour, and generally bivouacked in hastily-pitched tents, sometimes even in the open air, these marches supplied an excellent opportunity for growing accustomed to the fatigues of military life. It is clear from all this that the instruction of the ephebi bore a half-gymnastic, half-military character, and thus chiefly aimed at physical development; yet, on the other hand, many opportunities were given the young men for further intellectual development. We cannot, of course, determine whether the majority of them took advantage of this, for undoubtedly it was optional, and not immediately connected with their necessary training. However, in the second century B.C. the custom prevailed of letting the presidents of the various gymnasia at Athens see that they were regularly attended.

Higher Education in Ancient Greece

As regards the subjects of this more advanced instruction, opportunity was certainly given for further study in arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy, as well as music and drawing. After the fourth century the various schools of philosophy which arose at that time, began to take a very important place in the intellectual development of these youths. As early as the fifth century the Sophists gave instruction to young and older men for payment; but after the time of Plato the higher instruction was regularly organised and also given free of charge, and from this time forward it was closely connected with the training of the ephebi, since the gymnasia destined for gymnastic teaching were also used for instruction in philosophy.

Plato and his school taught, as is well known, in the Academy; Aristotle and the Peripatetics in the Lyceum; and Antisthenes and the Cynic school in the Cynosarges; the Stoics also originally taught at the Lyceum, but afterwards in the Stoa Poikile (the “painted portico”) near the old Agora; at Athens the Epicurean school only was not connected with any existing gymnasium. This connection, however, between these schools and the gymnasia was merely an external one, and really meant that the ground and gardens belonging to them were situated in the domain of these special gymnasia. However, the fact that the schools possessed a fixed place under the direction of the head for the time being did very much to establish their stability. We must not regard these philosophical schools as higher schools in the modern sense; though each school had a head who had the management in his own hands, and at his death appointed a successor, yet there was no question of an organised scheme of studies or of instruction regularly occupying certain hours of the day, or, indeed, of any of the conditions which could be compared with our modern universities, at any rate not before the period of the Roman Empire.

In the fourth century and in the Hellenistic period the instruction merely consisted in a discourse given by the head, or a disputation with his scholars, by means of which the various branches of philosophy and ethics were treated. Practical instruction in rhetoric was also given, sometimes by philosophers, but oftener by celebrated rhetoricians, such as Isocrates, and this training lasted several years. Very often young men prepared themselves in this way for their future career as statesmen or lawyers; and in the Hellenistic period the study of philological grammar began to gain importance, especially in the schools of Alexandria, Pergamum, and Antioch, to which places celebrated teachers attracted numerous pupils. These studies were in no way connected with the regular training of ephebi.

Aristotle on Molding Good Citizens Through Education

Aristotle wrote in “The Politics,” Book III (c.340 B.C.): Like the sailor, the citizen is a member of a community. Now, sailors have different functions, for one of them is a rower, another a pilot, and a third a look-out man...Similarly, one citizen differs from another, but the salvation of the community is the common business of them all. This community is the constitution; the virtue of the citizen must therefore be relative to the constitution of which he is a member. A constitution is the arrangement of magistracies in a state, especially of the highest of all. The government is everywhere sovereign in the state, and the constitution is in fact the government. For example, in democracies the people are supreme, but in oligarchies, the few; and, therefore, we say that these two forms of government also are different: and so in other cases. [Source: Thatcher, ed., Vol. II: The Greek World, pp. 364-382; The Politics of Aristotle, translated by Benjamin Jowett, (New York: Colonial Press, 1900]

Aristotle wrote in “The Politics,” Book VII: “The citizen should be molded to suit the form of government under which he lives. And since the whole city has one end, it is manifest that education should be one and the same for all, and that it should be public, and not private. Neither must we suppose that any one of the citizens belongs to himself, for they all belong to the state, and are each of them a part of the state, and the care of each part is inseparable from the care of the whole.

“The customary branches of education are in number four; they are — (1) reading and writing, (2) gymnastic exercises, (3) music, to which is sometimes added (4) drawing. Of these, reading and writing and drawing are regarded as useful for the purposes of life in a variety of ways, and gymnastic exercises are thought to infuse courage. Concerning music a doubt may be raised. — in our own day most men cultivate it for the sake of pleasure, but originally it was included in education, because nature herself, as has been often said, requires that we should be able, not only to work well, but to use leisure well; for, what ought we to do when at leisure? Clearly we ought not to be amusing ourselves, for then amusement would be the end of life. But if this is inconceivable, we should introduce amusements only at suitable times, and they should be our medicines, for the emotion which they create in the soul is a relaxation, and from the pleasure we obtain rest.....

Plutarch on Specialized Training Versus General Education for All

Plutarch wrote in “The Training of Children” (c. A.D. 110): “11. In the next place, the exercise of the body must not be neglected; but children must be sent to schools of gymnastics, where they may have sufficient employment that way also. This will conduce partly to a more handsome carriage, and partly to the improvement of their strength. For the foundation of a vigorous old age is a good constitution of the body in childhood. Wherefore, as it is expedient to provide those things in fair weather which may be useful to the mariners in a storm, so is it to keep good order and govern ourselves by rules of temperance in youth, as the best provision we can lay in for age. Yet must they husband their strength, so as not to become dried up (as it were) and destitute of strength to follow their studies. For, according to Plato, sleep and weariness are enemies to the arts. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

“But why do I stand so long on these things? I hasten to speak of that which is of the greatest importance, even beyond all that has been spoken of; namely, I would have boys trained for the contests of wars by practice in the throwing of darts, shooting of arrows, and hunting of wild beasts. For we must remember in war the goods of the conquered are proposed as rewards to the conquerors. But war does not agree with a delicate habit of body, used only to the shade; for even one lean soldier that has been used to military exercises shall overthrow whole troops of mere wrestlers who know nothing of war.

But, somebody may say, while you profess to give precepts for the education of all free-born children, why do you carry the matter so as to seem only to accommodate those precepts to the rich, and neglect to suit them also to the children of poor men and plebeians? To which objection it is no difficult thing to reply. For it is my desire that all children whatsoever may partake of the benefit of education alike; but if yet any persons, by reason of the narrowness of their estates, cannot make use of my precepts, let them not blame me that give them for Fortune, which disabled them from making the advantage by them they otherwise might. Though even poor men must use their utmost endeavor to give their children the best education; or, if they cannot, they must bestow upon them the best that their abilities will reach. Thus much I thought fit here to insert in the body of my discourse, that I might the better be enabled to annex what I have yet to add concerning the right training of children.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024