HOMOSEXUALITY IN ANCIENT GREECE

Tomb of the Diver symposium Homosexuality in ancient Greek was tolerated and regarded as no big deal, and, by some, even considered even fashionable. But apparently not everybody. Orpheus was dismembered by the Maenads for advocating homosexual love.

Among the Greeks homosexuality was common, especially in the military. Some have argued that homosexuality may have been the norm for both men and women and heterosexual sex was primarily just to have babies.

Sexual contact occurred among males in the bath houses. Gymnasiums, where naked men and boys, exercised and worked out together, were regarded as breeding grounds for homo-erotic impulses. At the extreme end, members of Magna Mat cults dressed in women’s clothes and sometimes castrated themselves.

Some have argued that homosexual marriages of some kind were widely accepted in classical antiquity and that the medieval church continued the pagan practice. There arguments though tend to be weak and based on anecdotal material. There is no proof that such marriages existed in Greek and Roman culture except among the elite in imperial Roman smart set. Other evidence of homosexual marriages come from isolated or marginal regions, such as post-Minoan Crete, Scythia, Albania, and Serbia, all of which had unique and sometimes bizarre local traditions.

In ancient times men sometimes made a pledge by putting their hands on their testicles as if to say, "If I am lying you can cut off my balls." The practice of making a pledge on the Bible is said to have its roots in this practice.

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Greek History (48 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Art and Culture (21 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Life, Government and Infrastructure (29 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ; Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT rtfm.mit.edu; 11th Brittanica: History of Ancient Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

Mary Renault’s “ The Mask of Apollo” contains descriptions of romantic homosexual affairs.

Homosexuality, Education and Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great probably had gay lovers. Although he was married twice some historians claim Alexander was a homosexual who was in love with his childhood friend, closest companion and general — Hephaestion. Another lover was a Persian eunuch named Bagoas. But many say that his truest love was his horse Bucephalas.

Relationships between older men and teenage boys was believed to be common. In “ Clouds” Aristophanes wrote: "How to be modest, sitting so as not to expose his crotch, smoothing out the sand when he arose so that the impress of his buttocks would not be visible, and how to be strong...The emphasis was on beauty...A beautiful boy is a good boy. Education is bound up with male love, an idea that is part of the pro-Spartan ideology of Athens...A youth who is inspired by his love of an older male will attempt to emulate him, the heart of educational experience. The older male in his desire of the beauty of the youth will do whatever he can improve it."

In Aristophanes's “ The Birds” , one older man says to another with disgust: "Well, this is a fine state of affairs, you demanded desperado! You meet my son just as he comes out of the gymnasium, all rise from the bath, and don't kiss him, you don't say a word to him, you don't hug him, you don't feel his balls! And you're supposed to be a friend of ours!"

Homosexuality, Militarism and Sports in Ancient Greece

Homosexuality and athleticism were said to have gone hand in hand in ancient Greece. Ron Grossman wrote in Chicago Tribune, “Far from finding homosexuality and athleticism mutually exclusive, they considered gay sex an excellent training regimen and an inspiration for military valor.” Plato said, “if there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made of lovers they would overcome the world.”

Homosexuality appears to have been the norm in ancient Sparta for both men and women with more than a touch of sadomasochism thrown in. The Spartans believed that beating was good for the soul. Heterosexual sex was primarily just to have babies. Young boys were paired with older boys in a relationship that had homosexual overtones. Plutarch wrote: “They were favored with the society of young lovers among the reputable young men...The boy lovers also shared with them in their honor and disgrace.”

When a boy reached 18, they were trained in combat. At twenty they moved into a permanent barrack-style living and eating arrangement with other men. They married at any time, but lived with men. At 30 they were elected to citizenship. Before a Sparta wedding , the bride was usually kidnapped, her hair was cut short and she dressed as a man, and laid down on a pallet on the floor. "Then," Plutarch wrote, "the bride groom...slipped stealthily into the room where his bride lay, loosed her virgin's zone, and bore her in his arms to the marriage-bed. Then after spending a short time with her, he went away composedly to his usual quarters, there to sleep with the other men."||

The Sacred Band was an army unit and warrior caste from Thebes, northwest of Athens. Ranked second in fierceness after the Spartans and celebrated in the song “Boeotia”, the region of Greece from which they were from,, they were often paired with theirs lovers under the assumption they would fight harder for their lover than they would for themselves. It was said they never were defeated in battle until Greece lost its independence to Philip II of Macedonia. But even then Philip was moved by their bravery. Plutarch wrote: “When after the battle, Philip was surveying the dead, and stopped at the place where the 300 were lying and learned that thus was a band of lovers and beloved, he burst into tears and said, “Perish, miserably they who think that these men died or suffered anything disgraceful.”

Sappho and Lesbians in Ancient Greece

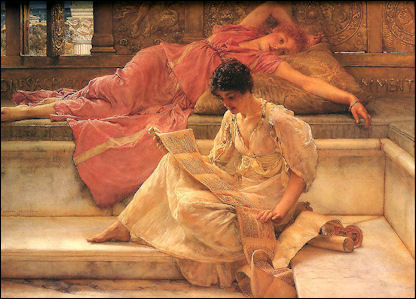

Alma-Tadema's view of a

woman reading poetry Sappho wrote sensuously about love between females. The word "lesbian" comes from her home island of Lesbos. Born in 610 B.C. in Lesbos, off of Asia Minor, she was probably from a noble family and her father was probably a wine merchant. Little is known about her because she didn't write much about herself and few others did.

In Sappho's time, Lesbos was inhabited by the Aeolians, a people known for free thinking and liberal sexual customs. Women had more freedom than they did in other places in the Greek world and Sappho is believed to have received a quality education and moved in intellectual circles.

Sappho formed a society for women in which women were taught arts such as music, poetry and chorus singing for marriage ceremonies. Although the relationship between Sappho and the women in her society is unclear she wrote about love and jealousy she felt for them. In spite of this, she had a child named Kleis and may have been married.

In his book “The First Poets”, Michael Schmidt speculates on where she was born and raised on Lesbos: was it in the western village of Eressus in rough, barren country, or in the cosmopolitan eastern seaport of Mytilene? He subtly evokes her poetic style: ''Sappho's art is to dovetail, smooth and rub down, to avoid the over-emphatic.'' And he aptly compares the relationship between voice and musical accompaniment in Sappho's performance of her poems to the recitative in opera. [Source: Camille Paglia, New York Times, August 28, 2005]

Over the centuries passionate arguments over Sappho's character, public life and sexual orientation have sprung up. Even though there is no direct reference to homosexual or heterosexual sex religious leaders — including Pope Gregory VIII, who called her a "lewd nymphomaniac in 1073 — ordered her books burned.

See Sappho Under Poetry Under Literature

Greece a Homosexual Paradise?

Paul Halsall wrote in “People with a History: An Online Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Trans History”: “For modern western gays and lesbians, Ancient Greece has long functioned as sort of homosexual Arcadia. Greek culture was, and is, highly privileged as one of the foundations of Western culture and the culture of sexuality apparent in its literature was quite different from the "repression" experienced by moderns. The sense of possibility the Greek experienced opened up can be seen in a scene in E.M. Forster's “Maurice” where the hero is seen reading Plato's Symposium at Cambridge.

“It would be too simple, however, to see Greek homosexuality as just a more idyllic form than modern versions. As scholars have gone to work on the — plentiful — material several tropes have become common. One set of scholars (slightly old-fashioned now) looks for the "origin" of Greek homosexuality, as if it were a new type of game, and argues that, since the literature depicts homosexual eros among the fifth-century aristocracy, it functioned as sort of fashion among that group. This is rather like arguing that because nineteenth-century English novels depict romance as an activity of the gentry and aristocracy, other classes did not have romantic relationships.

“Another, now more prevalent, group of scholars argue that term "homosexual", referring they say to sexual orientation, is inappropriate to discussions of Greek sexual worlds. Rather they stress the age dissonance in literary homoerotic ideals, and the importance of "active" and "passive" roles. Some stress these themes so intently that it comes as a surprise to discover that we now know the names of quite number of long-term Greek homosexual couples.

“As a result of such scholarly discussions, it is no longer possible to portray Greece as a homosexual paradise. It remains the case that the Greek experience of eros was quite different from experiences in the modern world, and yet continues, because of Greece's persistent influence on modern norms to be of special interest.”

Sources on Homosexuality in Ancient Greece

Paul Halsall wrote in a 1986 graduate school paper titled “Homosexual Eros in Early Greece”: “Homer and Hesiod give some idea of pre-archaic mores concerning erotic desire. From the archaic period itself we have a wealth of erotic poetry - Sappho, the lone female witness, Anacreon, Ibycus and Solon all writing lyric poetry and Theognis, whose elegiac corpus was later conveniently divided into political and pederastic sections. Classical sources include Aristophanes' comedy and some comments from Thucydides and Herodotus. Plato: writes frequently about eros, above all in the Symposium and Phraedrus but just as instructive are comments in other dialogues about Socrates relationships with a number of younger men. The speech of Aischines against Timarchus gives a good example of oratory on homosexual acts from the 4th century.” Another “group of sources are scraps of information we can draw from the vocabulary used about erotic desire, information we have about laws and privileges in certain cities and modern prosopography that can identify phenomena like the homosexualisation of mythical persons which occurred in our period.

“Homer's heroes have strong emotional bonds with each other but erotic desire is directed at women. Achilles' love for Patroclus was seen later as homosexual but despite the effect of Patroclus' death no physical relationship is mentioned. Hesiod is not much concerned with eros at all but he is clearly describing a country life where a man's chief end was to produce sons. There have been attempts to say that homosexuality entered Greek culture with the arrival of the Dorians. The wide acceptance of homosexuality in Dorian cities is cited as the grounds for this. Our earliest evidence of a culture of homosexual eros comes however from Ionian Solon and Aeolian Sappho rather than Dorian Tyrtaeus. It is not then a question of homosexuality coming from anywhere. What we have is a situation where early sources show no emphasis on homosexuality then fairly quickly toward’s the end of the 7th century the appearance of homosexual poems, followed on by vases and more poems in the early 6th century. The geographical extent of the phenomenon makes attempts to ascribe homosexuality to more leisure on behalf of the Athenian aristocracy untenable. Sparta was not at leisure nor many other cities with tyrannies where homosexuality was as acceptable as in Athens.

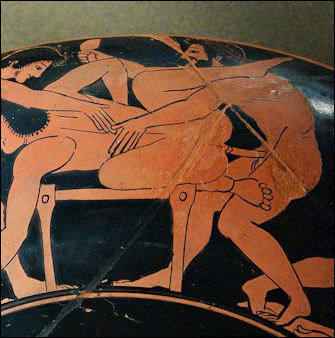

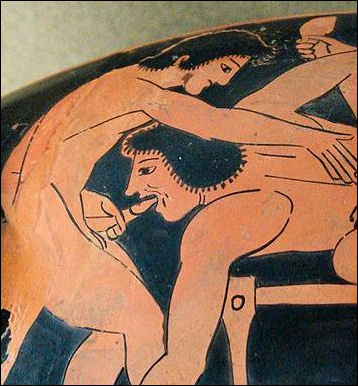

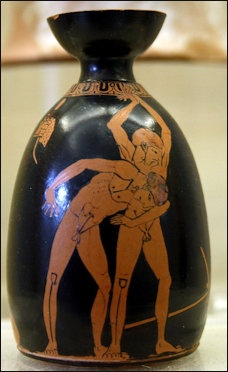

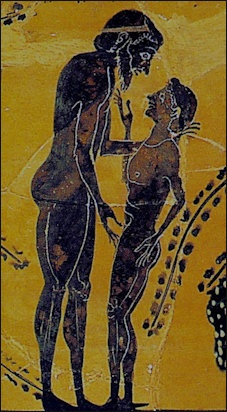

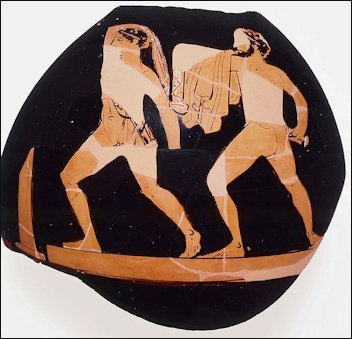

“More testimony to homosexual Eros effect on culture can be seen in the visual arts, both on vase decorations and in statues. Even when no homosexual encounter is portrayed these works exhibit a strong appreciation of the male body, much more so than the female body which is often draped. It is legitimate to use these works to determine what the canons or beauty were. The archaic ideal was of a tanned muscled youth after the' onset of puberty but before a strong beard had grown. It was a beauty formed by the particular physical education of Greek youth and is sympathetically parodied by Aristophanes as consisting of "a powerful chest, a healthy skin, broad shoulders. a big arse and a small cock". Satyrs it may be noted are depicted as contrary to this in every particular.”

Sodomy in Antiquity

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: Paedico means to pedicate, to sodomise, to indulge in unnatural lewdness with a woman often in the sense of to abuse. In Martial’s Epigrams 10, 16 and 31 jesting allusion is made to the injury done to the buttocks of the catamite by the introduction of the 'twelve-inch pole' of Priapus. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com] Orpheus is supposed to have introduced the vice of sodomy upon the earth. In Ovid's Metamorphoses: He also was the first adviser of the Thracian people to transfer their love to tender youths ...presumably in consequence of the death of Eurydice, his wife, and his unsuccessful attempt to bring her to earth again from the infernal regions. But he paid dearly for his contempt of women. The Thracian dames whilst celebrating their bacchanal rites tore him to pieces.

François Noël, however, states that Laius, father of Oedipus, was the first to make this vice known on earth. In imitation of Jupiter with Ganymede, he used Chrysippus, the son of Pelops, as a catamite; an example which speedily found many followers. Amongst famous sodomists of antiquity may be mentioned: Jupiter with Ganymede; Phoebus with Hyacinthus; Hercules with Hylas; Orestes with Pylades; Achilles with Patrodes, and also with Bryseis; Theseus with Pirithous; Pisistratus with Charmus; Demosthenes with Cnosion; Gracchus with Cornelia; Pompeius with Julia; Brutus with Portia; the Bithynian king Nicomedes with Caesar,[1] &c., &c. An account of famous sodomists in history is given in the privately printed volumes of 'Pisanus Fraxi', the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (1877), the Centuria Librorum Absconditorum (1879) and the Catena Librorum Tacendorum (1885).

Male Friendship in Ancient Greece: Brothers in Arms

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

J. Addington Symonds wrote: “Nearly all the historians of Greece have failed to insist upon the fact that fraternity in arms played for the Greek race the same part as the idealization of women for the knighthood of feudal Europe. Greek mythology and history are full of tales of friendship, which can only be paralleled by the story of David and Jonathan in the Bible. The legends of Herakles and Hylas, of Theseus and Peirithous, of Apollo and Hyacinth, of Orestes and Pylades, occur immediately to the mind. Among the noblest patriots, tyrannicides, lawgivers, and self-devoted heroes in the early times of Greece, we always find the names of friends and comrades received with peculiar honor Harmodius and Aristogeiton, who slew the despot Hipparchus at Athens; Diocles and Philolaus, who gave laws to Thebes; Chariton and Melanippus, who resisted the sway of Phalaris in Sicily; Cratinus and Aristodemus, who devoted their lives to propitiate offended deities when a plague had fallen on Athens; these comrades, staunch to each other in their love, and elevated by friendship to the pitch of noblest enthusiasm, were among the favorite saints of Greek legend and history. In a word, the chivalry of Hellas found its motive force in friendship rather than in the love of women; and the motive force of all chivalry is a generous, soul-exalting, unselfish passion. The fruit which friendship bore among the Greeks was courage in the face of danger, indifference to life when honor was at stake, patriotic ardor, the love of liberty, and lion-hearted rivalry in battle. Tyrants,' said Plato, ' stand in awe of friends."' [Source: “Studies of the Greek Poets.” By J. S. Symonds, Vol. I, p. 97, Edward Carpenter's “Ioläus,”1902]

On the customs connected with this fraternity in arms, in Sparta and in Crete, Karl Otfried Muller wrote in “History and Antiquities of the Doric Race,” book iv., ch. 4, par. 6: “At Sparta the party loving was called eispnelas and his affection was termed a breathing in, or inspiring (eispnein); which expresses the pure and mental connection between the two persons, and corresponds with the name of the other, viz.: aitas i.e., listener or hearer. Now it appears to have been the practice for every youth of good character to have his lover; and on the other hand every well-educated man was bound by custom to be the lover of some youth. Instances of this connection are furnished by several of the royal family of Sparta; thus, Agesilaus, while he still belonged to the herd (agele) of youths, was the hearer (aitas) of Lysander, and himself had in his turn also a hearer; his son Archidamus was the lover of the son of Sphodrias, the noble Cleonymus; Cleomenes III was when a young man the hearer of Xenares, and later in life the lover of the brave Panteus. The connection usually originated from the proposal of the lover; yet it was necessary that the listener should accept him with real affection, as a regard to the riches of the proposer was consid ered very disgraceful; sometimes, however, it happened that the proposal originated from the other party. The connection appears to have been very intimate and faithful; and was recognized by the State. If his relations were absent. the youth might be represented in the public assembly by his lover; in battle too they stood near one another, where their fidelity and affection were often shown till death; while at home the youth was constantly under the eyes of his lover, who was to him as it were a model and pattern of life; which explains why, for many faults, particularly want of ambition, the lover could be punished instead of the listener." [Source: Karl Otfried Muller (1797-1840), “History and Antiquities of the Doric Race,” book iv., ch. 4, par. 6]

"This ancient national custom prevailed with still greater force in Crete; which island was hence by many persons considered as the original seat of the connection in question. Here too it was disgraceful for a well-educated youth to be without a lover; and hence the party loved was termed Kleinos, the praised; the lover being simply called philotor. It appears that the youth was always carried away by force, the intention of the ravisher being previously communicated to the relations, who, however, took no measures of precaution and only made a feigned resistance; except when the ravisher appeared, either in family or talent, unworthy of the youth. The lover then led him away to his apartment (andreion), and afterwards, with any chance companions, either to the mountains or to his estate. Here they remained two months (the period prescribed by custom), which were passed chiefiy in hunting together. After this time had expired, the lover dismissed the youth, and at his departure gave him, according to custom, an ox, a military dress, and brazen cup, with other things; and frequently these gifts were increased by the friends of the ravisher. The youth then sacrificed the ox to Jupiter, with which he gave a feast to his companions: and now he stated how he had been pleased with his lover; and he had complete liberty by law to punish any insult or disgraceful treatment. It depended now on the choice of the youth whether the connection should be broken off or not. If it was kept up, the companion in arms (parastates), as the youth was then called, wore the military dress which had been given him, and fought in battle next his lover, inspired with double valor by the gods of war and love, according to the notions of the Cretans; and even in man's age he was distinguished by the first place and rank in the course, and certain insignia worn about the body.

“Institutions, so systematic and regular as these, did not exist in any Doric State except Crete and Sparta; but the feelings on which they were founded seem to have been common to all the Dorians. The loves of Philolaus, a Corinthian of the family of the Bacchiadae, and the lawgiver of Thebes, and of Diocles the Olympic conqueror, lasted until death; and even their graves were turned towards one another in token of their affection; and another person of the same name was honored in Megara, as a noble instance of self-devotion for the object of his love." For an account of Philolaus and Diocles, Aristotle (Pol. ii. 9) may be referred to. The second Diocles was an Athenian who died in battle for the youth he loved. “His tomb was honored with the enagismata of heroes, and a yearly contest for skill in kissing formed part of his memorial celebration." [Source: J. A Symonds ”A Problem in Greek Ethies,” privately printed, 1883; see also Theocritus, Idyll xii. infra]

In his Albanesische Studien, Johann Georg Hahn (1811-1869) says that the Dorian customs of comradeship still flourish in Albania “just as described by the ancients,”and are closely entwined with the whole life of the people-though he says nothing of any military signification. It appears to be a quite recognized institution for a young man to take to himself a youth or boy as his special comrade. He instructs, and when necessary reproves, the younger; protects him, and makes him presents of various kinds. The relation generally, though not always ends with the marriage of the elder. The following is reported by Hahn as in the actual words of his informant (an Albanian): "Love of this kind is occasioned by the sight of a beautiful youth; who thus kindles in the lover a feeling of wonder and causes his heart to open to the sweet sense which springs from the contemplation of beauty. By degrees love steals in and takes possession of the lover, and to such a degree that all his thoughts and feelings are absorbed in it. When near the beloved he loses himself in the sight of him; when absent he thinks of him only.”These loves, he continued, “are with a few exceptions as pure as sunshine, and the highest and noblest affections that the human heart can entertain." (Hahn, vol. I, p. 166.) Hahn also mentions that troops of youths, like the Cretan and Spartan agelae, are formed in Albania, of twenty-five or thirty members each. The comradeship usually begins during adolescence, each member paying a fixed sum into a common fund, and the interest being spent on two or three annual feasts, generally held out of doors. \=\

Sacred Band of Thebes

Modern interpretation of the Sacred Band of Thebes

Edward Carpenter wrote in “Ioläus”: "The Sacred Band of Thebes, or Theban Band, was a battalion composed entirely of friends and lovers; and forms a remarkable example of military comradeship. The references to it in later Greek literature are very numerous, and there seems no reason to doubt the general truth of the traditions concerning its formation and its complete annihilation by Philip of Macedon at the battle of Chaeronea (B.C. 338). Thebes was the last stronghold of Hellenic independence, and with the Theban Band Greek freedom perished. But the mere existence of this phalanx, and the fact of its renown, show to what an extent comradeship was recognized and prized as an institution among these peoples. [Source: Edward Carpenter's “Ioläus,”1902]

The following account is taken from Plutarch's Life of Pelopidas, Clough's translation: “Gorgidas, according to some, first formed the Sacred Band of 300 chosen men, to whom as being a guard for the citadel the State allowed provision, and all things necessary for exercise; and hence they were called the city band, as citadels of old were usually called cities. Others say that it was composed of young men attached to each other by personal affection, and a pleasant saying of Pammenes is current, that Homer's Nestor was not well skilled in ordering an army, when he advised the Greeks to rank tribe and tribe, and family and family, together, that so 'tribe might tribe, and kinsmen kinsmen aid,' but that he should have joined lovers and their beloved. For men of the same tribe or family little value one another when dangers press; but a band cemented together by friendship grounded upon love is never to be broken, and invincible: since the lovers, ashamed to be base in sight of their beloved, and the beloved before their lovers, willingly rush into danger for the relief of one another. Nor can that be wondered at since they have more regard for their absent lovers than for others present; as in the instance of the man who, when his enemy was going to kill him, earnestly requested him to run him through the breast, that his lover might not blush to see him wounded in the back. It is a tradition likewise that Ioläus, who assisted Hercules in his labors and fought at his side, was beloved of him; and Aristotle observes that even in his time lovers plighted their faith at Ioläus' tomb. It is likely, therefore, that this band was called sacred on this account; as Plato calls a lover a divine friend. It is stated that it was never beaten till the battle at Chaeronea; and when Philip after the fight took a view of the slain, and came to the place where the three hundred that fought his phalanx lay dead together, he wondered, and understanding that it was the band of lovers, he shed tears and said, ' Perish any man who suspects that these men either did or suffered anything that was base.' \=\

“It was not the disaster of Laius, as the poets imagine, that first gave rise to this form of attachment among the Thebans, but their law-givers, designing to soften whilst they were young their natural fickleness, brought for example the pipe into great esteem, both in serious and sportive occasions, and gave great encouragement to these friendships in the Palaestra, to temper the manner and character of the youth. With a view to this, they did well again to make Harmony, the daughter of Mars and Venus, their tutelar deity; since where force and courage is joined with gracefulness and winning behavior, a harmony ensues that combines all the elements of society in perfect consonance and order. \=\

“Gorgidas distributed this sacred Band all through the front ranks of the infantry, and thus made their gallantry less conspicuous; not being united in one body, but mingled with many others of inferior resolution, they had no fair opportunity of showing what they could do. But Pelopidas, having sufficiently tried their bravery at Tegyrae, where they had fought alone, and around his own person, never afterwards divided them, but keeping them entire, and as one man, gave them the first duty in the greatest battles. For as horses run brisker in a chariot than single, not that their joint force divides the air with greater ease, but because being matched one against another circulation kindles and enflames their courage; thus, he thought, brave men, provoking one another to noble actions, would prove most serviceable and most resolute where all were united together." \=\

Romantic Friendship Among Ancient Greek Soldiers

Spartan warriors

Stories of romantic friendship form a staple subject of Greek literature, and were everywhere accepted and prized. Athenaeus wrote: “And the Lacedaemonians [Spartans] offer sacrifices to Love before they go to battle, thinking that safety and victory depend on the friendship of those who stand side by side in the battle array.... And the regiment among the Thebans, which is called the Sacred Band, is wholly composed of mutual lovers, indicating the majesty of the God, as these men prefer a glorious death to a shameful and discreditable life." [Source: Athenaeus, bk. xiii., ch. 12, Edward Carpenter's “Ioläus,”1902]

Ioläus is said to have been the charioteer of Hercules, and his faithful companion. As the comrade of Hercules he was worshipped beside him in Thebes, where the gymnasium was named after him. Plutarch alludes to this friendship again in his treatise on Love: “And as to the loves of Hercules, it is difficult to record them because of their number; but those who think that Ioläus was one of them do to this day worship and honor him, and make their loved ones swear fidelity at his tomb." And in the same treatise: “Consider also how love (Eros) excels in warlike feats, and is by no means idle, as Euripides called him, nor a carpet knight, nor ' sleeping on soft maidens' cheeks.' For a man inspired by Love needs not Ares to help him when he goes out as a warrior against the enemy, but at the bidding of his own god is ' ready ' for his friend ' to go through fire and water and whirlwinds.' And in Sophocles' play, when the sons of Niobe are being shot at and dying, one of them calls out for no helper or assister but his lover. [Plutarch, Eroticus, par. 17]

“And you know of course how it was that Cleomachus, the Pharsalian, fell in battle.... When the war between the Eretrians and Chalcidians was at its height, Cleomachus had come to aid the latter with a Thessalian force; and the Chalcidian infantry seemed strong enough, but they had great difficulty in repelling the enemy's cavalry. So they begged that high-souled hero, Cleomachus, to charge the Eretrian cavalry first. And he asked the youth he loved, who was by, if he would be a spectator of the fight, and he saying he would, and affectionately kissing him and putting his helmet on his head, Cleomachus, wlth a proud joy, put himself at the head of the bravest of the Thessalians, and charged the enemy's cavalry with such impetuosity that he threw them into disorder and routed them; and the Eretrian infantry also fleeing in consequence, the Chalcidians won a splendid victory. However, Cleomachus got killed, and they show his tomb in the market place at Chalcis, over which a huge pillar stands to this day." [Source: Eroticus, par. 17, trans. Bohn's Classics.]

And further on in the same: \“And among you Thebans, Pemptides, is it not usual for the lover to give his boylove a complete suit of armor when he is enrolled among the men ? And did not the erotic Pammenes change the disposition of the heavy-armed infantry, censuring Homer as knowing nothing about love, because he drew up the Achaeans in order of battle in tribes and clans, and did not put lover and love together, that so ' spear should be next to spear and helmet to helmet' (lliad, xiii. 131), seeing that love is the only invincible general. For men in battle will leave in the lurch clansmen and friends, aye, and parents and sons, but what warrior ever broke through or charged through lover and love, seeing that when there is no necessity lovers frequently display their bravery and contempt of life."

Homosexual Life in Athens and Ancient Greece

Paul Halsall wrote in a 1986 graduate school paper titled “Homosexual Eros in Early Greece”: “Origins of cultural homosexuality are better found in the social life of the 7th and 6th centuries rather than in any historical event. Greece was more settled than in the 8th and early 7th centuries. We have evidence of a growing population - the number of graves in Attica increased six-fold [5]- and bigger cities. The position of women was down graded in cities where only men were citizens. In the cities new social settings grew up for men; in gymnasiums men wrestled and ran naked; the symposium or drinking party became a part of city life, and again it was men only. In this situation homosexuality came to the fore. This seems to have been a period of cultural openness and the Greeks had no revealed books to tell them that homosexuality was wrong. It is an oddity of our culture that men often refuse to acknowledge the beauty of another man. The Greeks had no such inhibitions. They were meeting each other daily in male only settings, women were less an less seen as emotional equals and there was no religious prohibition of the bisexuality every human being is physically equipped to express. At the same time there was an artistic flowering in both poetry and visual arts. A cultural nexus of art and homosexual eros was thus established and homosexuality became a continuing part of Greek culture.

male couples

“Athens is always central to our appreciation of Greek history but we can be seriously mistaken if we take homosexuality to be an Athenian habit or try to explain it in purely Athenian terms. Athens became more peaceful in the 7th and 5th centuries but this was not true of the Peloponnese and similarly there may have been democratisation of culture in Athens - but not in Sparta or Macedonia. There is in fact evidence that romantic eros was seen as homosexual all over Greece. Sparta, even with its relatively free women, had homosexual relationships built into the structure of the training all young Spartan men received . In other Dorian areas also homosexuality was widely accepted. Thebes saw in the 4th century the creation of a battalion of homosexual lovers - the Sacred Band. In Crete we have evidence of ritualised abduction of younger by older men.

“Elsewhere Anacreon-'s portrayal of Polycrates' court at Samos, and the history of homosexual lovers of the kings of Macedon confirm the extended appreciation of same sex couplings in Greek society. This being so, it seems to be methodologically unsound to use events in Athenian social history to explain the nature of eros in early Greece even if perforce most of our evidence comes from there. Once established the link between homosexual eros and art gained wide acceptance. This is reflected in the cultural product of the archaic period. For poets eros was a major source of subject and inspiration. Solon may be taken as an example”

Blest is the man who loves and after early play

Whereby his limbs are supple made and strong

Retiring to his house with wine and song

Toys with a fair boy on his breast the livelong day !

“Anacreon, Ibycus, Theognis and Pindar share Solon's tastes. Although poems were dedicated to women what is particular to the archaic period is the valuing of homosexual over heterosexual eros. Plato's speakers in the Symposium hold love between men as higher than any other form as it was lover between equals; men were held to be on a moral and intellectual plane higher than women. One of the most extraordinary features of the period was the homosexualisation of myth. Ganymede was only Zeus' servant in Homer but now became seen as his beloved. The passion of Achilles and Patroclus was similarly cast in sexual terms.

“The acme of homosexual love in Athens came about at the end of the Persistratid tyranny at Athens. It fell for a variety of reasons and there was certainly no immediate switch to democracy but in later Athenian history two lovers, Aristogeiton and Harmodios were given the credit of bringing down the tyrants. Thucydides makes it clear that what happened was that Hipparchus, the brother of the tyrant Hippias, was killed because he made a pass at Harmodios and when rejected proceeded to victimise his family [8]. Thucydides regards all this as slightly sordid, although it has been suggested his motives in rubbishing the tyrannicides was to promote the Alcmeonids as founders of Athenian democracy [9]. Whatever actually happened an extraordinary cult of the two lovers grew up in Athens with their descendants being given state honours such as front seats at the theatre even at the height of radical democracy when such honours were frowned upon. In Athens at least this cult was used repeatedly to give kudos to homosexual couples and what they could achieve for society.

“The theme was exploited philosophically by Plato. In the Symposium he applies the terminology of procreation to homosexual love and says that, while it does not produce children it brings forth beautiful ideas, art and actions which were eternally valuable. Although Plato visualises relationships in lover-beloved terms his philosophy makes it clear that reciprocity was expected between the lovers.

Homosexual Relations in Ancient Greece

Greek poet Anacreon and his lover

Paul Halsall wrote in a 1986 graduate school paper titled “Homosexual Eros in Early Greece”: “Poetry, pottery and philosophy leave no doubt as to the acceptability of homosexual eros. Just how much it was valued is much harder to estimate. For Athens the best evidence comes in Pausanias' speech in Plato's Symposium. Here Pausanias makes it clear that a lover in full flight was approved of by Athenians, who had expectations of how a lover should show his love. These included sleeping in his beloved's doorway all night to prove his love. The other side of the story was that fathers were- not at all keen on their sons being pursued and took steps to preserve their son's chastity . Here we have a case of the male/female double standard being applied to homosexual affairs. The conventional attitude was that it was good to be a lover but not to be passive. A boy only remained respectable if he gave into a lover slowly and even then he could not allow any public compromise of his masculinity. Passivity was seen as essentially unmasculine. This ambivalence continues in Athenian history and the Timarchus prosecuted by Aischines in 348 faced as the major charge an accusation that he had enjoyed passivity and thus put himself in the same position as a prostitute. Away from Athens the matter is not quite so clear. In Sparta boys were encouraged to take lovers, in Crete there was a ritual of abduction and the beloved side of the couples in Thebes' Sacred Band were not castigated as unmasculine. Homosexual eros was valued in art, in philosophy, in heroic couples and as part of a boys education. What did worry Athenians at least was when conventions were not kept to and masculinity was compromised.

“If homosexual relationships were only known as short affairs they are strangely at odds with the elevated nature of eros described by Plato who seems to envisage a lifelong joint search for truth. We should not be misled by statues of old father Zeus abducting young and innocent Ganymede. Although it was accepted that there should be an age difference between lovers this need not be very great. Vase paintings often show youths with boys where the erastes/eromenos distinction is maintained but without much disparity in years. Anal intercourse when shown is almost always between coevals. Aristophanes in the Symposium spins a myth of eros being the result of a single person cut in half trying to find and re-unite with the other half; this more or less implies an expectation that lovers would not be to disparate in age. While not ruling out a decade or so in age difference, we must allow that if a youth was going to form a relationship involving sex with another man he would want and admire somebody in their prime. The realities of the army and gymnasium would ensure a limited age distribution also - the very young nor very old would not be either numerous or admired for their prowess. Homosexual affairs then would take place between men of comparable age and some of them lasted many years - Agathon with his lover in the Symposium, Socrates in his relationship with Alcibiades, who broke all the rules by chasing an older man, and the couples in Thebes' army are all testimony to homosexual 'marriages'. It is however not clear if affairs continued after either party married. Other men were for emotional relationships but alliances and children depended on women. The age of marriage was 30, by convention, and affairs may have reached natural conclusions at that age. We have no evidence either way.

“As well as conventions on age there were accepted practices in sex, exhibited very well on vase paintings. It is I suggest simply unreasonable to believe that 16-20 year olds, as portrayed on vases, had no sexual response and only unwillingly allowed themselves to be penetrated inter-crurally without any pleasure. Here we have a case of conventions far removed from actuality. While keeping in mind that we hear of no relationships without the active-passive roles, it is clear that writers in contrast to painters expected homosexual sex to include anal penetration; Aristophanes uses the epithet "europroktos"(wide-arsed) for men with a lot of experience of being penetrated. Greek convention decried the passive partner in penetrative intercourse and we may assume that both partners took care that their private pleasures were not made public. It is useful to recall that Greek morals were concerned with what was known not what was done and unlike cases such as dishonouring a guest there was no divine sanction against sexual pleasures, which indeed the gods seemed to enjoy in abundance. In short I think Aristophanes' humour is more reliable than vases. Penetration was important to the Greek idea of what sex was which was why their major distinction was between active and passive rather than 'straight' or 'gay'. What went on behind closed doors probably did not accord with convention.”

Male Ancient Greek Couples

Paul Halsall wrote: “There is no doubt that classical Greek literature frequently presents a distinct model of homosexual eros. The proposed relationship is between a an older man (the lover or erastes) and a younger man (the beloved or eromenos). This ideal has much influenced discussion of the subject, and has lead some commentators to limit the connections between ancient Greek homosexually active men and modern "homosexuals": old-style historians emphasized that "homosexuality" was a phenomenon of the upper classes, opposed to democracy, and become less common in the more "heterosexual" Hellenistic period; modern "cultural historians" have argued repeatedly that the "homosexual" (conceived as an individual [or "subject"] defined by his or her sexual orientation) is a modern "social construction".

It is worthwhile retaining such considerations when studying the texts about homosexuality in Ancient Greece: the proposers of these ideas are serious scholars whose views demand respect. Nevertheless, such views can become a rigid orthodoxy. The fact of the matter is that there are all sorts of texts relating to homosexuality surviving from Ancient Greece, and many of these texts reveal that the literary ideal was not indicative of much practice; nor, even, the only ideal of homosexual love.

Here, then are textual references for long-term (in some cases life-long) homosexual relationships in the Greek texts; 1) Orestes and Pylades: Orestes is the hero of the Oresteia cycle. He and Pylades were bywords for faithful and life-long love in Greek culture, see Lucian (2nd C. CE): Amores or Affairs of the Heart, #48. 2) Damon and Pythias: Pythagorean initiates, see Valerius Maximus: De Amicitiae Vinculo. 3) Aristogeiton and Harmodius, credited with overthrowing tyranny in Athens, see Thucydides, Peloponnesian War, Book 6. 4) Pausanias and Agathon: Agathon was an Athenian dramatist (c. 450-400 BCE). He was famous as an "effeminate" homosexual. It was in his house that the Dinner Party of Plato's Symposium takes place. see Plato: Symposium 193C, Aristophanes: Thesmophoriazusae. 5) Philolaus and Diocles -Philolaus was a lawgive at Thebes, Diocles an Olympic Athlete, see Aristotle, Politics 1274A. 6) Epaminondas and Pelopidas: Epaminondas (c.418-362 BCE) led Thebes in its greatest days in the fourth century. At the battle of Mantinea (385 BCE) he saved the life of his life long friend Pelopidas, see Plutarch: Life of Pelopidas. 7) Members of the Sacred Band of Thebes, see Plutarch: Life of Pelopidas. 8) Alexander the Great and Hephasteion, Atheaneus, The Deinosophists Bk 13.

Aristogeiton and Harmodius, Gay Lovers Who Overthrew the Athenian Tyrrany

During the Peloponnesian War, an group of vandals went around Athens knocking the phalluses off Hermes - the steles with the head and phallus of the God Hermes which were often outside houses. This incident, which lead to suspicions of the Athenian general Alciabiades, provided Thucydides with a spring board to recount the story of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, two homosexual lovers credited by the Athenians with overthrowing tyranny.

Thucydides wrote in “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” 6th. Book (ca. 431 B.C.): ““Indeed, the daring action of Aristogiton and Harmodius was undertaken in consequence of a love affair, which I shall relate at some length, to show that the Athenians are not more accurate than the rest of the world in their accounts of their own tyrants and of the facts of their own history. Pisistratus dying at an advanced age in possession of the tyranny, was succeeded by his eldest son, Hippias, and not Hipparchus, as is vulgarly believed. Harmodius was then in the flower of youthful beauty, and Aristogiton, a citizen in the middle rank of life, was his lover and possessed him. Solicited without success by Hipparchus, son of Pisistratus, Harmodius told Aristogiton, and the enraged lover, afraid that the powerful Hipparchus might take Harmodius by force, immediately formed a design, such as his condition in life permitted, for overthrowing the tyranny. In the meantime Hipparchus, after a second solicitation of Harmodius, attended with no better success, unwilling to use violence, arranged to insult him in some covert way. Indeed, generally their government was not grievous to the multitude, or in any way odious in practice; and these tyrants cultivated wisdom and virtue as much as any, and without exacting from the Athenians more than a twentieth of their income, splendidly adorned their city, and carried on their wars, and provided sacrifices for the temples. For the rest, the city was left in full enjoyment of its existing laws, except that care was always taken to have the offices in the hands of some one of the family. Among those of them that held the yearly archonship at Athens was Pisistratus, son of the tyrant Hippias, and named after his grandfather, who dedicated during his term of office the altar to the twelve gods in the market-place, and that of Apollo in the Pythian precinct. The Athenian people afterwards built on to and lengthened the altar in the market-place, and obliterated the inscription; but that in the Pythian precinct can still be seen, though in faded letters, and is to the following effect: “Pisistratus, the son of Hippias,/ Sent up this record of his archonship/ In precinct of Apollo Pythias. [Source: Thucydides, “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” 6th. Book, ca. 431 B.C., translated by Richard Crawley]

“That Hippias was the eldest son and succeeded to the government, is what I positively assert as a fact upon which I have had more exact accounts than others, and may be also ascertained by the following circumstance. He is the only one of the legitimate brothers that appears to have had children; as the altar shows, and the pillar placed in the Athenian Acropolis, commemorating the crime of the tyrants, which mentions no child of Thessalus or of Hipparchus, but five of Hippias, which he had by Myrrhine, daughter of Callias, son of Hyperechides; and naturally the eldest would have married first. Again, his name comes first on the pillar after that of his father; and this too is quite natural, as he was the eldest after him, and the reigning tyrant. Nor can I ever believe that Hippias would have obtained the tyranny so easily, if Hipparchus had been in power when he was killed, and he, Hippias, had had to establish himself upon the same day; but he had no doubt been long accustomed to overawe the citizens, and to be obeyed by his mercenaries, and thus not only conquered, but conquered with ease, without experiencing any of the embarrassment of a younger brother unused to the exercise of authority. It was the sad fate which made Hipparchus famous that got him also the credit with posterity of having been tyrant.

Harmodius and Aristogeiton

“To return to Harmodius; Hipparchus having been repulsed in his solicitations insulted him as he had resolved, by first inviting a sister of his, a young girl, to come and bear a basket in a certain procession, and then rejecting her, on the plea that she had never been invited at all owing to her unworthiness. If Harmodius was indignant at this, Aristogiton for his sake now became more exasperated than ever; and having arranged everything with those who were to join them in the enterprise, they only waited for the great feast of the Panathenaea, the sole day upon which the citizens forming part of the procession could meet together in arms without suspicion. Aristogiton and Harmodius were to begin, but were to be supported immediately by their accomplices against the bodyguard. The conspirators were not many, for better security, besides which they hoped that those not in the plot would be carried away by the example of a few daring spirits, and use the arms in their hands to recover their liberty.

“At last the festival arrived; and Hippias with his bodyguard was outside the city in the Ceramicus, arranging how the different parts of the procession were to proceed. Harmodius and Aristogiton had already their daggers and were getting ready to act, when seeing one of their accomplices talking familiarly with Hippias, who was easy of access to every one, they took fright, and concluded that they were discovered and on the point of being taken; and eager if possible to be revenged first upon the man who had wronged them and for whom they had undertaken all this risk, they rushed, as they were, within the gates, and meeting with Hipparchus by the Leocorium recklessly fell upon him at once, infuriated, Aristogiton by love, and Harmodius by insult, and smote him and slew him. Aristogiton escaped the guards at the moment, through the crowd running up, but was afterwards taken and dispatched in no merciful way: Harmodius was killed on the spot.

“When the news was brought to Hippias in the Ceramicus, he at once proceeded not to the scene of action, but to the armed men in the procession, before they, being some distance away, knew anything of the matter, and composing his features for the occasion, so as not to betray himself, pointed to a certain spot, and bade them repair thither without their arms. They withdrew accordingly, fancying he had something to say; upon which he told the mercenaries to remove the arms, and there and then picked out the men he thought guilty and all found with daggers, the shield and spear being the usual weapons for a procession.

“In this way offended love first led Harmodius and Aristogiton to conspire, and the alarm of the moment to commit the rash action recounted. After this the tyranny pressed harder on the Athenians, and Hippias, now grown more fearful, put to death many of the citizens, and at the same time began to turn his eyes abroad for a refuge in case of revolution. Thus, although an Athenian, he gave his daughter, Archedice, to a Lampsacene, Aeantides, son of the tyrant of Lampsacus, seeing that they had great influence with Darius. And there is her tomb in Lampsacus with this inscription: “Archedice lies buried in this earth,/ Hippias her sire, and Athens gave her birth; / Unto her bosom pride was never known.” Though daughter, wife, and sister to the throne. Hippias, after reigning three years longer over the Athenians, was deposed in the fourth by the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) and the banished Alcmaeonidae, and went with a safe conduct to Sigeum, and to Aeantides at Lampsacus, and from thence to King Darius; from whose court he set out twenty years after, in his old age, and came with the Medes to Marathon.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018