CHILDREN IN ANCIENT GREECE

Bronze statue of Eros sleeping

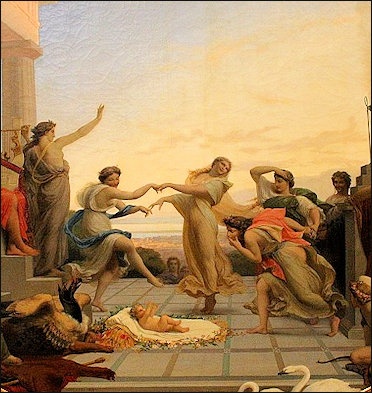

The Greeks seemed to be very fond of young children. In ancient Greek art they were depicted as children doing children things not as mini adults as was the case with ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Infants were often depicted in works of art and lyricists wrote poems about being woken up in the middle of the night and taking care of a crying baby. Archaeologists in Athens uncovered a ceramic "potty" and an urn showing a child sitting on the potty shaking a rattle; apparently the rattle was to show he was done.

On a socio-economic and spiritual level, it was important for Greeks to have children. People who died unmarried and childless were thought to have tormented and unresolved souls which could come back to haunt relatives. Children were also seen as insurance policies for old age; it was their responsibility to take care of their parents when they got old. To pay respects to the older generation, children were often named after their grandparents in a ceremony in which the infant's mother ran around a hearth with the infant in her arms ten days after the birth. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,]

Children grew up playing with pets such as dogs, ducks, mice and, even, insects. Rites of passage included three-year-old children being given their first jug, from which they had their first taste of wine, and older children taking their toys to a temple to be consecrated signifying the official end of their childhood. "Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from The Classical Past” was the name of an exhibit held at a number of museums in the 2000s, including Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum and the Onassis Cultural Center in New York. Among the objects displayed there were a sculpture of a woman carrying a child on he shoulders; papyri with school exercises; vase paintings of children playing with pets; images of children playing chariot with goat- propelled carts.

The renderings of children on the vases is quite natural. They are depicted with love Jennifer Neils, a classics professor at Case Western University and co-curator of the exhibit, told U.S. News and World Report, “You can see them making baby gestures, reaching for their mothers.” She said one of her favorite images was a an image on a cup of a baby with outstretched on a high chair that likely doubled as a potty. “It’s almost like a little peephole, a view into a secluded home life. It shows what a mother treasurers — her relationship with her baby.”

See Separate Articles: CHILD REARING IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ; EDUCATION IN ANCIENT GREECE factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past”

by Jenifer Neils , John H. Oakley , et al. (2003) Amazon.com;

“Children in Antiquity: Perspectives and Experiences of Childhood in the Ancient Mediterranean” by Lesley A. Beaumont, Matthew Dillon, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World” by Judith Evans Grubbs and Tim Parkin (2013) Amazon.com;

“Constructions of Childhood in Ancient Greece and Italy” by Ada Cohen, Jeremy B. Rutter (2007) Amazon.com;

“Children and Childhood in Classical Athens” (Ancient Society and History)

by Mark Golden (1990) Amazon.com;

“Childhood in Ancient Athens: Iconography and Social History” by Lesley A. Beaumont (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Family in Greek History” by Cynthia B. Patterson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Family” by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges (1830-1889) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Houses and Households: Chronological, Regional, and Social Diversity”

by Bradley A. Ault and Lisa C. Nevett (2005) Amazon.com;

“Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion” by Matthew Dillon (2002) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Greece” by Susan Blundell (1995) Amazon.com;

Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” (Classic Reprint) by Alice Zimmern (1855-1939) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: Life and Customs” by E. Guhl and W. Koner (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Life of the Ancient Greeks, With Special Reference to Athens”

by Charles Burton (1868-1962) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

Birth of a Child in Ancient Greek

Ben Gazur wrote in Listverse: Childbirth before the invention of anesthetics and modern medicine was brutal, painful, and dangerous. Euripides has Medea in his play declare, “I had rather stand my ground three times among the shields than face a childbirth once.”Is it any wonder then that women sought ways to avoid the horrors of the birthing bed? [Source Ben Gazur, Listverse, January 7, 2017]

We after the child is born lets transport ourselves in imagination to the house of an Athenian citizen of the better classes. He is a rich man, who not only owns a comfortable, though simple, town house and land outside the gate managed by slaves, but also draws considerable interest from capital invested in trading vessels, and from the numerous slaves who work in factories for wages. But, in spite of his comfortable circumstances, his joy has hitherto been troubled by one sorrow — he has been married for several years, and as yet no heir to his possessions has been given him. A little daughter is growing up in the house to the joy of her parents, but even this cannot console the father for the sad prospect of seeing the possessions inherited from his ancestors, and increased by his own industry and economy, pass into the hands of strangers. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

But to-day joy and gladness have entered this man’s house. His wife has borne him the much-longed-for son and heir. The neighbours, who had seen the well-known nurse enter the house, were anxious to see in what manner the front door would be decked — whether, as before, woollen fillets would announce the birth of a daughter, or the joyous wreath of olive branches proclaim the advent of a son and heir.

While the slaves are festively decking the door outside, within the house the new-born child is receiving its first care. With a happy smile the young mother looks on from her couch while the nurse and maids are busily occupied in preparing the bath for the little one. For this only tepid water and fine oil are used, for the Spartan custom of adding wine to the baby’s first bath is unknown at Athens. After the bath, too, the baby has a warmer bed than would have fallen to his lot in the sterner city.

Care for an Infant in Ancient Greece

Little babies were tightly bound in swaddling clothes soon after birth, and the mother, in anxiety for her child’s safety, usually fastened an amulet or charm of some kind around its neck to keep away unfriendly spirits. The grotesque faces of colored glass previously mentioned may have served this purpose. The baby became the charge of an old and trusted slave-woman such as the kind old nurse represented in a terracotta statuette. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

With Athenian family mentioned, perhaps the father intends, as soon as possible, to send to Sparta for one of those celebrated nurses known and prized for their success in rearing children; but still he shrinks from beginning the hardening process at this tender age, and rearing up the child according to Spartan customs without the warm swaddling clothes. So the baby is carefully wrapped in numerous swaddlings, in such a manner that even the arms are firmly swathed, and only the little head is visible. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The ancient physicians prescribe for the new-born child soft woollen swaddling three fingers broad, and direct that the swaddling should begin with the hands, then pass on to the chest, and at last cover the feet, swathing each part separately but loosely, only drawing the bandages tight at the knees and the soles of the feet; the head also must be enveloped, and, finally, a second covering is put over the whole body. When modern physicians maintain that this swaddling must injure the child and check the development of its organs, they forget that the Greeks treated their children thus for centuries and yet were a healthy nation. But it is quite incredible that they should have been thus swaddled for the first two years of their life, as a passage in Plato seems to indicate, for this would not only have been extraordinary, but also injurious to the health. It can only be a question of maintaining a covering suitable to the age for these two years, instead of the children’s dress afterwards worn.

A physician of the age of the Empire recommends the end of the fourth month as the time for gradually leaving off the swaddling; and probably this was also the Greek custom. Antiquity does not seem to have been acquainted with our soft cushions, but the little Athenians also had their cradles, though these did not stand on the ground on rockers like ours, for such cradles are not mentioned till the Roman period, and seem to have been unknown in the classic age; but they resembled a basket of woven osier, suspended from ropes like a hammock, and thus made to rock. The cradle in which Hermes, who seems already to have attained the age of boyhood, is depicted on a vase painting is of a peculiar shape, quite like that of a shoe; the handles at the side, through which ropes were probably passed, show that this was also made to rock. Another image shows a different kind of cradle. It is a bed on rockers, which may have been used in the same way as the babies’ cots common among us.

The young mother now for the first time gives the new-born baby the breast, and rejoices that she is able to perform this duty herself. However, in case she should not have been able to do it, a poor peasant woman from the neighbourhood had been brought to the house and paid for her services. Meanwhile, the husband sits down by the bed and discusses with his wife the steps which must next be taken. A question that sometimes causes a good deal of difficulty presents none on this occasion — such as the legitimation of the child. And as the boy is strong and healthy, there cannot be a question of the barbarous custom of exposing it, which, though rarely resorted to at Athens, was still quite common at Sparta. Even had the child been a second daughter, the kindly-disposed master of the house would not have resorted to this cruel step; although, had he done so, his fellow-citizens would not have blamed him for it.

Plutarch on Taking Care of Infants

Plutarch wrote in “The Training of Children” (c. A.D. 110): “The nursing of children...in my judgment, the mothers should do themselves, giving their own breast to those they have borne. For this office will certainly be performed with more tenderness and carefulness by natural mothers, who will love their children intimately, as the saying is, from their tender nails. Whereas, both wet and dry nurses, who are hired, love only for their pay, and are affected to their work as ordinarily those that are substituted and deputed in the place of others are. Yes, even Nature seems to have assigned the suckling and nursing of the issue to those that bear them: for which cause she has bestowed upon every living creature that brings forth young milk to nourish them. And, in conformity thereto, Providence has only wisely ordered that women should have two breasts, that so, if any of them should happen to bear twins, they might have two several springs of nourishment ready for them. Though, if they had not that furniture, mothers would still be more kind and loving to their own children. And that not without reason; for constant feeding together is a great means to heighten the affection mutually betwixt any persons. Yes, even beasts, when they are separated from those that have grazed with them, do in their way show a longing for the absent. Wherefore, as I have said, mothers themselves should strive to the utmost to nurse their own children. [Plutarch was born of a wealthy family in Boeotia at Chaeronea about 50 A.D. Part of his life seems to have been spent at Rome, but he seems to have returned to Greece and died there about 120 A.D. But little further is know of his life. He was one of the greatest biographers the world has ever known, while his moral essays show wide learning and considerable depth of contemplation. Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

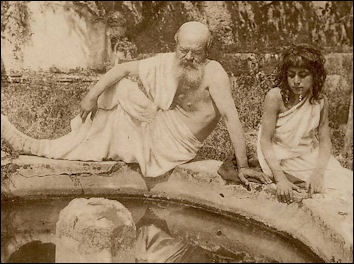

Socrates with a student

by Wilhelm von Gloeden

“But if they find it impossible to do it themselves, either because of bodily weakness (and such a case may fall out), or because they are apt to be quickly with child again, then are they to choose the most honest nurses they can get, and not to take whomsoever they have offered them. And the first thing to be looked after in this choice is, that the nurse be bred after the Greek fashion. For as it is needful that the members of children be shaped aright as soon as they are born, that they may not afterwards prove crooked and distorted, so it is no less expedient that their manners be well-fashioned from the very beginning. For childhood is a tender thing, and easily wrought into any shape. Yes, and the very souls of children readily receive the impressions of those things that are dropped into them while they are yet but soft; but when they grow older, they will, as all hard things are, be more difficult to be wrought upon. And as soft wax is apt to take the stamp of the seal, so are the minds of children to receive the instructions imprinted on them at that age. Whence, also, it seems to me good advice which divine Plato gives to nurses, not to tell all sorts of common tales to children in infancy, lest thereby their minds should chance to be filled with foolish and corrupt notions. The like good counsel Phocylides, the poet, seems to give in this verse of his: “If we'll have virtuous children, we should choose/ Their tenderest age good principles to infuse.

“6. Nor are we to omit taking due care, in the first place, that those children who are appointed to attend upon such young nurslings, and to be bred with them for play-fellows, be well-mannered, and next that they speak plain, natural Greek; lest, being constantly used to converse with persons of a barbarous language and evil manners, they receive corrupt tinctures from them. For it is a true proverb, that if you live with a lame man, you will learn to halt.

Celebration for the Birth of a Child in Ancient Greece

Not long after the birth of son, parents have to settle on which day the family festival shall take place, to welcome and dedicate with religious rites the newborn child (Amphidromia) and what name they shall give it. They decide upon the tenth day after the birth for the festival. Many parents, it is true, celebrate this as early as the fifth day, and then on the tenth hold a second festival with an elaborate banquet and sacrifices, and but few rich people content themselves with a single celebration. But though in this case there is no lack of means, yet, as the young mother wishes to take part herself in the Amphidromia, they decide to be content with one celebration, which is to take place in ten days. According to old family custom, the boy receives the name of his paternal grandfather.

When the appointed day has come, and the house is festively decked with garlands, messengers begin to arrive early in the morning from relations and friends, bringing all manner of presents for the mother and child. For the former they bring many dishes which will be useful at the banquet in the evening, especially fresh fish, polypi, and cuttle-fish. The baby receives various gifts, especially amulets to protect him against the evil eye. For, according to widespread superstition, these innocent little creatures are specially exposed to the influence of evil magic. Therefore the old slave, to whom the parents have confided the care of the child, chooses from among the various presents a necklace which seems to her especially suitable as an antidote to magic, on which are hung all manner of delicately-worked charms in gold and silver: such as a crescent, a pair of hands, a little sword, a little pig, and anything else which popular superstition may include in the ranks of amulets; and hangs this round the child’s neck. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The festival begins with a sacrifice, and is followed by the solemnity in which mother and child, who, according to ancient notions, are regarded as unclean by the act of birth, are purified or cleansed, along with all who have come in contact with the mother. This part of the ceremony is the real “Amphidromia” (literally “running round”). The nurse takes the child on her arm, and, followed by the mother and all who have come in contact with her, runs several times round the family hearth, which, according to ancient tradition, represents the sacred center of the dwelling. Probably this was accompanied by sprinkling with holy water.

At the banquet the relations and friends of the family appear in great numbers. In their presence the father announces the name which he has chosen for the child. After this all take their places at the banquet, even the women, who, as a rule, do not take part in the meals of the men. The standing dishes on this occasion are toasted cheese and radishes with oil; but there is no lack of excellent meat dishes such as breast of lamb, thrushes, pigeons, and other dainties, as well as the popular cuttle-fish. A good deal of wine is drunk, mixed with less water than is generally the custom. Music and dancing accompany the banquet, which extends far into the night.

Hardships for Children in Ancient Greece

family tomb in Athens The Greeks were not quite so loving if there was something wrong with the child. The Spartan checked newborn infants for physical deformities and mental problems; if an abnormality was discovered the child was tossed off a cliff. Citizens in less violet city-states left their unwanted children outdoors to die of exposure, or abandoned them in the marketplace where they could be claimed as slaves. The latter is what happened to Oedipus Rex in the Sophocles play...so maybe his parents deserved what they had coming to them. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

Some parents reportedly rarely saw their children. There were sharp differences in education opportunities given boys and girls and those given the children of aristocrats and slaves. One image on a piece of pottery shows a slave girls suffering under a heavy load while her mistress relaxes with a glass of wine. another shows a naked girl being taught to dance for male prinking parties.

Early death was an unfortunate reality in the ancient world. Parents commissioned tombstones and works of pottery that lovingly rendered dead children playing with pets. One for a girl named Melisto shows her holding a doll in one hand and a pet bird in another. Sadness over loss was also reflected in poems. One goes:

“ Here I stand Emainete, daughter of Prokles

Fate took me away from my pet birds and my maid

I was granted a dirge instead of a husband.

This grave instead of a husband” .

Infanticide was common. Pat Smith, a physical archaeologist at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, told National Geographic, “We know that infanticide was widely practiced by the Greeks and Romans. It was regarded as the parents’ right if they didn’t want a child. Usually they killed girls. Boys were considered more valuable — as heirs for support in old age. Girls were sometimes viewed as burdens, especially if they needed a dowry to marry.”

Toddlers and Young Children in Ancient Greece

The first years of his life were spent by the little boy in the nursery, in which things went on in much the same way as with us. During this period boys and girls alike were under the supervision of mother and nurse. If the baby had bad nights and could not sleep, the Athenian mother took him in her arms just as a modern one would do, and carried him up and down the room, rocking him, and singing some cradle song like that which Alcmene sings to her children in Theocritus:

“Sleep, children mine, a light luxurious sleep.

Brother with brother: sleep, my boys, my life:

Blest in your slumber, in your waking blest.”

[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

At night a little lamp burnt in the nursery. Although, as a rule, in small houses the apartments for the men were below and those for the women and children in the upper storeys, yet it was customary for the women to move into the lower rooms for a time after the birth of a child, partly in order that they might be near the bath-room, which was necessary both for mother and child. During the first years of their life the children had a tepid bath every day; later on, every three or four days; many mothers even went so far as to give them three baths a day. When the child had to be weaned, they first of all gave it broth sweetened with honey, which, in olden time, took the place of our sugar, and then gradually more solid food, which the nurse seems to have chewed for the child before it had teeth enough to do this itself. Aristophanes gives us further details about Greek nurseries, and even quotes the sounds first uttered by Athenian children to make known their various wants.

The custom of letting the nurses draw the children in perambulators in the street seems to have been unknown, but baby-carriages, in which the children were drawn about in the room, are mentioned by the ancient physicians. Ancient Greek writers do not seem to have had any special mechanical contrivances for learning to walk. In the time of the Empire baskets furnished with wheels are mentioned. Apparently they were in no great hurry about this. For the first year or two the nurses carried the children out into the fields, or took them to visit their relations, or brought them to some temple; then they let them crawl merrily on the ground, and on numerous vase pictures we see children crawling on all fours to some table covered with eatables, or to their toys. When the child made its first attempt at walking, prudent nurses took care that it should not at first exert its feeble legs too much, and so make them crooked; though Plato probably goes too far when he desires to extend this care to the end of the third year, and advises nurses to carry the children till they have reached that age. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Children’s dress must have given but little trouble during these first years. At home — at any rate in summer — boys either ran about quite naked or else with only a short jacket open in front, like the little boy with the cart. The girls, however, had long dresses reaching to their feet, fastened by two ribbons crossing each other in front and behind. Naughty children were brought to obedience or quiet by threats of bogies, but, curiously enough, these Greek bogies were all female creatures, such as Medusae or witches: “Acco,” “Mormo,” “Lamia,” “Empusa,” etc.; and when the children would not stay quiet indoors, they seem to have threatened them with “The horses will bite you.” The mothers and nurses used to tell the children all sorts of legends and fairy tales — Aesop’s Fables were especially popular — and little stories from mythology or other tales of adventure, which often began, like ours, with the approved “Once upon a time.” Among the many poetical legends of gods and heroes there were, it is true, some which were morally or aesthetically objectionable, and the philosophers were not wrong in calling attention to the danger which might lie in this intellectual food, supplied so early to susceptible childish minds; yet this was undoubtedly less than what is found in our own children’s stories.

Thus our young Athenian spends the first years of his life amid merry play with his companions, under the watchful care of his mother. During the first six years the nursery, where girls and boys are together, is his world, though he is sometimes allowed to run about in the street with boys of his own age. He is not yet troubled with lessons, and although, should he be obstinate or naughty, his mother will sometimes chastise him with her sandal, yet in a family in which a right spirit prevails, the character of the education at this early age is a beneficent mixture of severity and gentleness. Sometimes, it is true, the father does not trouble himself at all about the education of his children, and leaves this entirely to his wife, who may lack the necessary intellectual capacity, or even to a female slave. This, of course, has bad results, and the same happens when the wife, like the mother of Pheidippides, in the “Clouds” of Aristophanes, is too ambitious for her little son, and, in constant opposition to the weak, though well-intentioned, father, spoils him sadly. Let us assume that the boy whose entrance into life we described above, is free from such deleterious influences, and, sound in mind and body, passes in his seventh year out of his mother’s hands into those which will now minister to his intellectual and physical development.

Children in Sparta

Toy horse, 10th century BCSpartan training began in the womb. A pregnant woman was required to do exercises to make sure her child was strong, The Spartans checked newborn infants for physical deformities and mental problems; if an abnormality was discovered the child was tossed off a cliff.

Spartan boys were taken from the mothers at the age of seven and moved into barracks and taught to be men until they were aged 20. The new recruits were bullied by older boys, forced to play brutal games and walk barefoot in the winter, and were ritually flogged in a temple devoted to the goddess of the hunt. Those that did well were made leaders. Young boys were paired with older boys in a relationship that had homosexual overtones. Plutarch wrote: “They were favored with the society of young lovers among the reputable young men...The boy lovers also shared with them in their honor and disgrace.”

The training was mostly in the form of physical drills and the martial arts. There was not so much instruction in philosophy, music or literature as was the case a the famous academies in Athens. Sometimes boys were purposely left hungry so they would steal food and develop shrewdness and resourcefulness.

When a boy reached 18, they were trained in combat. At twenty they moved into a permanent barrack-style living and eating arrangement with other men. They married at any time, but lived with men. At 30 they were elected to citizenship.

Children’s Toys in Ancient Greece

Children grew up playing with a variety of toys (rattles, balls, miniature chariots, wooden boats, clay houses; animal figures- pigs, goats, etc.). Excavated toys and include push carts, terra cotta tops, marbles, knucklebones, ivory counters, ivory dolls, dancing dolls with movable arms and castanets. Archaeologists have also found dice with the same number configurations as modern dice and a baby feeder inscribed with words "drink, don't drop." Greeks and Romans had dolls with human hair and movable limbs that joined to hip, shoulder and knee sockets with pins. Most Greek dolls were females. The few male Roman dolls that have been found were mostly male soldiers fashioned from wax and clay. By the Christian era infant dolls were popular and children dressed painted dolls in miniature clothes and placed them in doll houses. A terracotta horse from Cyprus with large jars in its panniers such as those carried by real horses for taking provisions to and from market. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

The word "marble" comes from the Greek “marmaros” , which means polished white agate. Marbles made from polished jasper and agate, dated at 1435 B.C., have been found in Crete. Yo yos are also believed to have been used in ancient Greece where they were made from wood, metal and terra cotta. Among the toys at the "Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from The Classical Past” exhibit were baby dolls and baby rattles in the shape of pigs. Kids seem to have been particularly fond of knucklebones made from the ankles of sheep and goats, They threw them like dice and carried them around in little pouch, John Oakley, a classics professor at the College of William and Mary told U.S. News and World Report, “They’re all over the place.” Girls were encouraged to juggle to improve their motor skills.

A very ancient toy is the rattle, usually a metal or earthenware jar filled with little stones, sometimes made in human form; and there were other noisy toys, with which the children played and the nurses strove to amuse them; though complaints were sometimes made that foolish nurses by these means prevented the children from going to sleep. The little girls liked to play with all kinds of earthenware vessels, pots, and dishes; and, like our little girls, they made their first attempts at cooking with these. Many such are found in the graves. More popular however, even in ancient times, were the dolls, made of wax or clay and brightly coloured; sometimes with flexible limbs or with clothes to take on and off, and representing all manner of gods, heroes, or mortals; dolls’ beds were also known. Though boys may have sometimes played with these figures, or even made them for themselves out of clay or wax, yet we generally find them in the hands of girls, who seem to have taken pleasure in them even after the first years of childhood; indeed, it was not uncommon, since Greek girls married very early, for them to play with their dolls up to the time of their marriage, and just before their wedding to take these discarded favorites, with their whole wardrobe, to some temple of the maiden Artemis, and there dedicate them as a pious offering. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

A very popular toy, found in many pictures in children’s hands, was a little two-wheeled cart, or else a simple solid wheel, without spokes, on a long pole — a cheap toy which could be purchased for an obol (about three-halfpence). Larger carriages were also used as toys, which the children drew themselves, and drove about their brothers and sisters or companions. Sometimes tame dogs or goats were harnessed to them, and the boys rode merrily along, cracking their whips. A small oinochoë shows a boy driving two goats harnessed to a chariot, and on a white lekythos painted for a child’s grave, a little boy is going to Charon’s boat for his journey over the Styx, drawing his toy cart. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Amusements and Games for Children in Ancient Greece

Swings were popular with both young and old. These were exactly like ours: either the rope itself was used as a seat and held fast with both hands, or else a comfortable seat was suspended from the cords. This was a merry game, in which grown-up women sometimes liked to take part; and so was the see-saw, of which even big girls made use. Sometimes the mother or older sister took the little boy by the arm and balanced him on her foot, as a girl does with Eros, and, as in the well-known beautiful statue, “The Little Dionysus,” is carried on the shoulders of a powerful satyr. Many a Greek father probably gave his son a ride on his shoulders. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Swings were popular with both young and old. These were exactly like ours: either the rope itself was used as a seat and held fast with both hands, or else a comfortable seat was suspended from the cords. This was a merry game, in which grown-up women sometimes liked to take part; and so was the see-saw, of which even big girls made use. Sometimes the mother or older sister took the little boy by the arm and balanced him on her foot, as a girl does with Eros, and, as in the well-known beautiful statue, “The Little Dionysus,” is carried on the shoulders of a powerful satyr. Many a Greek father probably gave his son a ride on his shoulders. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The boys delighted in other more masculine pleasures. They played with box-wood tops and whips, singing a merry song the while, or else they bowled their iron hoops, to which bells or rings were attached. The hoop was a favorite toy until the age of youth, and we often find it on vase paintings in the hands of quite big boys. We may certainly assume that they also had little imitations of warlike implements such as swords and shields; a little quiver, which can hardly have served any other purpose has been found. Clever boys made their own toys, and cut little carts and ships out of wood or leather, and carved frogs and other animals out of pomegranate rinds. Our hobby-horse, too, was known to the ancients, as is proved by a pretty anecdote told of Agesilaus. He was once surprised by a visitor playing with his children, and riding merrily about on a hobby-horse. It is said that he begged his friend not to tell of the position in which he had found the terrible general, until he should himself have children of his own. Kite-flying also was known to them, as is proved by a vase painting, which, though rough in drawing, distinctly shows the action.

They were also acquainted with the little wheels, turned by means of a string which is wound and unwound, that are still popular among the children of our day, and about a hundred years ago were fashionable toys known as “incroyables.” What we see in the boy’s hand can hardly be anything else. This was a game in which even grown-up people seem to have taken pleasure. On the vases of Lower Italy we often see in the hands of Eros, or women, a little wheel, with daintily jagged edge and spokes, fastened to a long string in such a way that, when this is first drawn tight by both hands and then let go, the wheel is set revolving. Probably this was not a mere toy when used by grown up people, but rather the magic wheel so often mentioned as playing a part in love charms; but about this we have no exact information.

It is a matter of course that the young people of that day were acquainted with all the games which can be played at social gatherings by children, without any assistance from without. The various games of running, catching, hiding, blind-man’s-buff, hide-and-seek, tug-of-war, , in which our young people still take pleasure, were played in Greece in just the same manner, as well as the manifold variety of games with balls, beans, nuts, pebbles, small coins, and bones. Games of ball served as recreation for youths and men, and some of the above-mentioned games of chance, rather than skill, were especially popular with grown-up people, particularly games of dice or “knuckle-bones.” As part of a game or perhaps as forfeit, girls sometimes carried one another on their backs. A terracotta statuette represents two girls playing ephedrismos, as this game was called. On one side of a toilet-box two girls are playing a game of ball with a wicket. Monkeys and dogs were kept as pets, and a few lucky children even got to have pet cheetahs.

Adoption in Ancient Greece

The Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) is the most complete surviving Greek Law code. According to the Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: “In Greek tradition, Crete was an early home of law. In the 19th Century, a law code from Gortyn on Crete was discovered, dealing fully with family relations and inheritance; less fully with tools, slightly with property outside of the household relations; slightly too, with contracts; but it contains no criminal law or procedure. This (still visible) inscription is the largest document of Greek law in existence (see above for its chance survival), but from other fragments we may infer that this inscription formed but a small fraction of a great code.” [Source:Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“XVII. Adoption may take place whence one will; and the declaration shall be made in the market-place when the citizens are gathered. If there be no legitimate children, the adopted shall received all the property as for legitimates. If there be legitimate children, the adopted son shall receive with the males the adopted son shall have an equal share. If the adopted son shall die without legitimate children, the property shall return to the pertinent relatives of the adopter. A woman shall not adopt, nor a person under puberty.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024