FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT GREECE

Most festivals were harvest festivals or religious festivals. As Greece became urbanized more people turned out for these festivals and the activities became more elaborate. Festivals were often financed by the state and were regarded as a reflection on the city's image.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The four most famous festivals, each with its own procession, athletic competitions, and sacrifices, were held every four years at Olympia, Delphi, Nemea, and Isthmia. These Panhellenic festivals were attended by people from all over the Greek-speaking world. Many other festivals were celebrated locally, and in the case of mystery cults, such as the one at Eleusis near Athens, only initiates could participate. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

The Greeks had some strange festivals associated with destroying things and ideas thought to be impure. During Bouphonia in Athens a sacrifice was held, then the ax used in the sacrifice was tried and condemned to death and thrown in the sea. After a hanging in Cos the rope and tree were banished. During the Ionian festival honoring Apollo sins were loaded onto a cart and taken out of town. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Comic playwrights had the most fun on the Day of Misrule, a holiday when nothing was sacred. Arcane philosophers were satirized, sexual morality was mocked, and even the gods were objects of ridicule.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RELATED ARTICLES:

SPORTS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SPORTS FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF THE OLYMPICS: ORIGIN, MYTHS, OLYMPIA, REBIRTH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK OLYMPICS: WHAT THEY WERE LIKE, ATMOSPHERE, PURPOSE europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Greek Holidays” by Mab Borden (2024) Amazon.com;

“Festivals of Attica: An Archaeological Commentary” by Erika Simon (1983) Amazon.com;

“Festivals of the Athenians” by H. W. Parke (1977) Amazon.com;

“The Mask of Apollo” by Mary Renault, (1966), novel, contains good descriptions of religious festivals. Amazon.com;

“Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World” by David Phillips and David Pritchard | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Eleusis and the Eleusinian Mysteries” by George Emmanuel Mylonas (2015) Amazon.com;

“Mystery Cults in the Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden (2023) Amazon.com;

“Dionysus: Myth and Cult” by Walter F. Otto (1995) Amazon.com;

“Dionysos: Exciter to Frenzy: a Study of the God Dionysos: History, Myth and Lore” by Vikki Bramshaw Amazon.com;

“Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore” by Jennifer Larson (2001) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Calendars: Constructions of Time in the Classical World”

by Robert Hannah (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Calendar: The 5000 Year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days” by David Ewing Duncan (1999) Amazon.com;

“A Short Introduction to the Ancient Greek Theater” by Graham Ley Amazon.com;

“The Greek Theatre and Festivals: Documentary Studies” (Oxford Studies in Ancient Documents) by Peter Wilson (2007) Amazon.com;

“Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth”

by Walter Burkert and Peter Bing (1972) Amazon.com;

“Savage Energies: Lessons of Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece” by Walter Burkert (2001) Amazon.com;

“Smoke Signals for the Gods: Ancient Greek Sacrifice from the Archaic Through Roman Periods” by F. S. Naiden (2012) Amazon.com;

“Animal Sacrifice in Ancient Greek Religion, Judaism, and Christianity, 100 BC to AD 200" by Maria-Zoe Petropoulou Amazon.com;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Greek Religion” by Esther Eidinow, Julia Kindt (2015) Amazon.com;

When and Where Ancient Greek Festivals Were Held

Festivals and feasts were held throughout the year. In Athens alone there were 120 days of festivals a year. Public festivals were often connected to some religious observance, the change of the seasons or some regular event connected with agriculture.

Generally, ancient Greek festivals were not celebrated at the same time by Greeks. There were a number of national festivals which were of equal importance to all Greeks; but these were not celebrated simultaneously throughout the country, but only at one specially appointed place, to which spectators came from all parts, and which thus provided an opportunity for great national meetings recurring at regular intervals. In consequence of the decentralisation of the country, these provided the only means of awakening and maintaining national feeling among the Greeks. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Other festivals were peculiar to particular countries, or even to towns or communities; the differences existing in Greek belief, which are often closely connected with national traditions and racial peculiarities, were also marked in the act of worship. Even those regular festivals which were celebrated alike in most of the Greek states were not all held on the same day, but at different times, which was probably due to the fact that Greek antiquity was acquainted with no common calendar. The proceedings at these festivals also differed greatly according to the place. We know very little about the majority; most details have come down to us concerning the Attic calendar and the customs in use there, though even here our knowledge is very incomplete. The great Hellenic national festivals, which were celebrated at Olympia, Delphi, Nemea, and on the isthmus of Corinth, will first claim our attention.

Sacrifices at Ancient Greek Festivals

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The central ritual act in ancient Greece was animal sacrifice, especially of oxen, goats, and sheep. Sacrifices took place within the sanctuary, usually at an altar in front of the temple, with the assembled participants consuming the entrails and meat of the victim. Liquid offerings, or libations, were also commonly made. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

sacrifice

As a rule, the first sacrifices to the heavenly deities were offered early in the day. There was a banquet in the afternoon, and thus opportunity was afforded for devoting the interval to entertainments, among which, along with song and dance, dramatic and gymnastic performances soon began to occupy a place, and gradually to assume the character of regular competitions. Sacrifices to the infernal deities took place in the afternoon or evening, and were, in consequence, followed by a festival at night, which sometimes degenerated into a wild orgy. These festivities, which were partly connected with the worship and partly celebrated for their own sake or connected with ancient national games, were at first a natural consequence of the religious ceremonies and the manner in which a nation of the cheerful disposition of the Greeks would celebrate them. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Hellas” (c. A.D. 175): “Every year too the people of Patrai celebrate the festival Laphria in honor of their Artemis, and at it they employ a method of sacrifice peculiar to the place. Round the altar in a circle they set up logs of wood still green, each of them sixteen cubits long. On the altar within the circle is placed the driest of their wood. Just before the time of the festival they construct a smooth ascent to the altar, piling earth upon the altar steps. The festival begins with a most splendid procession in honor of Artemis, and the maiden officiating as priestess rides last in the procession upon a car yoked to deer. It is, however, not till the next day that the sacrifice is offered, and the festival is not only a state function but also quite a popular general holiday. For the people throw alive upon the altar edible birds and every kind of victim as well; there are wild boars, deer and gazelles; some bring wolf-cubs or bear-cubs, others the full-grown beasts. They also place upon the altar fruit of cultivated trees. Next they set fire to the wood. At this point I have seen some of the beasts, including a bear, forcing their way outside at the first rush of the flames, some of them actually escaping by their strength. But those who threw them in drag them back again to the pyre. It is not remembered that anybody has ever been wounded by the beasts. [Source: Pausanias, Pausanias' Description of Greece, translated by A. R. Shilleto, (London: G. Bell, 1900)]

On the sacrifice of a bull at funeral ceremony, Plutarch wrote in “Life of Aristides” (c. A.D. 110): “And the Plataeans undertook to make funeral offerings annually for the Hellenes who had fallen in battle and lay buried there. And this they do yet unto this day, after the following manner. On the sixteenth of the month Maimacterion (which is the Boiotian Alakomenius), they celebrate a procession. This is led forth at break of day by a trumpeter sounding the signal for battle; wagons follow filled with myrtle-wreaths, then comes a black bull, then free-born youths carrying libations of wine and milk in jars, and pitchers of oil and myrrh (no slave may put hand to any part of that ministration, because the men thus honored died for freedom); and following all, the chief magistrate of Plataea, who may not at other times touch iron or put on any other raiment than white, at this time is robed in a purple tunic, carries on high a water-jar from the city's archive chamber, and proceeds, sword in hand, through the midst of the city to the graves; there he takes water from the sacred spring, washes off with his own hands the gravestones, and anoints them with myrrh; then he slaughters the bull at the funeral pyre, and, with prayers to Zeus and Hermes Terrestrial, summons the brave men who died for Hellas to come to the banquet and its copious drafts of blood; next he mixes a mixer of wine, drinks, and then pours a libation from it, saying these words: "I drink to the men who died for the freedom of the Hellenes."” [Source: Plutarch, “Plutarch’s Lives,” translated by John Dryden, (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1910)

Festival Entertainment in Ancient Greece

It is believed that festivals began as religious rites and entertainment was added later on. As performances and festivities came to be more closely connected with the religious festivals, they gradually became an integral part of them, and were no longer left to the arbitrary disposition of the persons concerned, but were taken in hand by the state or community, and subject to regular arrangement.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The entertainments most commonly added to the religious ceremonies at the festivals were, in the first place, those of a musical character, partly vocal, partly instrumental, or a combination of both; in the second, dances, both choric and pantomimic, lastly scenic representations, athletic contests, processions, national games, etc. Among these the musical, choregraphic, scenic, and gymnastic representations were first raised to the dignity of regular competitions. Of course, different festivals were celebrated in different ways; apart from local differences, the very character of the divinity in whose honour the festival was held, and the different phases of the legend, necessitated differences in the mode of celebration and in the regulation of those who were to take part in them; thus some festivals were celebrated by both sexes together, and others by only one, to the exclusion of the other.

Maenads In a letter to Ptolemaios, Demophon wrote (c. 245 B.C.): “Send us at your earliest opportunity the flutist Petoun with the Phrygian flutes, plus the other flutes. If it is necessary to pay him, do so, and we will reimburse you. Also, send us the eunuch Zenobius with a drum, cymbals, and castanets. The women need them for their festival. Be sure he is wearing his most elegant clothing. Get the special goat from Aristion and sent it to us. Send us also as many cheeses as you can, a new jug, and vegetables of all kinds, and fish if you have it. Your health! Throw in some policemen at the same time to accompany the boat.

Strabo wrote in “Geographia” (c. A.D. 20): “A festival is celebrated every year at Acharaca; and at that time in particular those who celebrate the festival can see and hear concerning all these things; and at the festival, too, about noon, the boys and young men of the gymnasion, nude and anointed with oil, take out a bull and with haste run before him into the cave; and, when they arrive at the cave, the bull goes forward a short distance, falls, and breathes out his life. [Source: Strabo, The Geography of Strabo: Literally Translated, with Notes, translated by H. C. Hamilton, & W. Falconer, (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857)

The Roman-era Greek orator Dio Chrysostom wrote (A.D. 110): “Some people attend the festival of the god out of curiousity, some for shows and contests, and many bring goods of all sorts for sale, the market folk, that is, some of whom display their crafts and manufactures while others make a show of some special learning — many, of works of tragedy or poetry, many, of prose works. Some draw worshipers from remote regions for religion's sake alone, as does the festival of Artemis at Ephesos, venerated not only in her home-city, but by Hellenes and barbarians.

Clementis Recognitiones wrote (c. A.D. 220): “Most men abandon themselves at festival time and holy days, and arrange for drinking and parties, and give themselves up wholly to pipes and flutes and different kinds of music and in every respect abandon themselves to drunkenness and indulgence.”

Herodotus on Ancient Greek Festivals

In his description of the encounter between Solon, the great wise Athenian, and the Lydian King Croesus, regarded as one of the richest men in the world at that time, Herodotus wrote in “Histories” (430 B.C.): “ There was a great festival in honour of the goddess Juno at Argos, to which their mother must needs be taken in a car. Now the oxen did not come home from the field in time: so the youths, fearful of being too late, put the yoke on their own necks, and themselves drew the car in which their mother rode. Five and forty furlongs did they draw her, and stopped before the temple. This deed of theirs was witnessed by the whole assembly of worshippers, and then their life closed in the best possible way. Herein, too, God showed forth most evidently, how much better a thing for man death is than life. [Source: Herodotus “The History of Herodotus” Book VI on the Persian War, 440 B.C.E, translated by George Rawlinson, MIT]

“For the Argive men, who stood around the car, extolled the vast strength of the youths; and the Argive women extolled the mother who was blessed with such a pair of sons; and the mother herself, overjoyed at the deed and at the praises it had won, standing straight before the image, besought the goddess to bestow on Cleobis and Bito, the sons who had so mightily honoured her, the highest blessing to which mortals can attain. Her prayer ended, they offered sacrifice and partook of the holy banquet, after which the two youths fell asleep in the temple. They never woke more, but so passed from the earth. The Argives, looking on them as among the best of men, caused statues of them to be made, which they gave to the shrine at Delphi."

On a Dionysus-style festival in Egypt, Herodotos wrote in “Histories” (c. 430 B.C.): “In other respects the festival is celebrated almost exactly as Dionysiac festivals are in Hellas, excepting that the Egyptians have no choral dances and no plays. They also use phalli four cubits [6 feet] high, pulled by ropes, which the women carry around, and whose male genitalia are operated by strings to go up and down. A piper goes in front, and the women follow, singing hymns in honor of Dionysos. The erection of the phallus, however, which the Hellenes observe in their statues of Hermes, they did not derive from the Egyptians, but from the Pelasgians; from them the Athenians adopted it, and afterwards it passed to the other Hellenes. The Athenians, then, were the first of the Hellenes to have an erect phallus.... [Source: Herodotus, “Histories”, translated by George Rawlinson, (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862)

Plutarch on Strange Ancient Greek Festivals

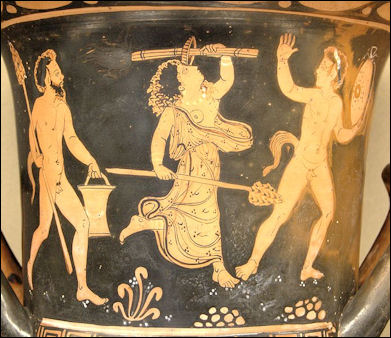

Dancing maenadPlutarch wrote in “Life of Alcibiades”(c. A.D. 110): “After the people had adopted this motion and all things were made ready for the departure of the fleet, there were some unpropitious signs and portents, especially in connection with the festival, namely, the Adonia. This fell at that time, and little images like dead folk carried forth to burial were in many places exposed to view by the women, who mimicked burial rites, beat their breasts, and sang dirges. Moreover, the mutilation of the Hermai, most of which, in a single night, had their faces and phalli disfigured, confounded the hearts of many, even among those who usually set small store by such things. They looked on the occurrence with wrath and fear, thinking it the sign of a bold and dangerous conspiracy. They therefore scrutinized keenly every suspicious circumstance, the council and the assembly convening for this purpose many times within a few days.” [Source: Plutarch, “Plutarch’s Lives,” translated by John Dryden, (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1910)

Plutarch wrote in “The Life of Theseos” (c. A.D. 110): “The feast called Oschophoria, or the feast of boughs, which to this day the Athenians celebrate, was then first instituted by Theseos. For he took not with him the full number of virgins which by lot were to be carried away [to the Labyrinth], but selected two youths of his acquaintance, of fair and womanish faces, but of a manly and forward spirit, and having, by frequent baths, and avoiding the heat and scorching of the sun, with a constant use of all the ointments and washes and dresses that serve to the adorning of the head or smoothing the skin or improving the complexion, in a manner changed them from what they were before, and having taught them farther to counterfeit the very voice and carriage and gait of virgins so that there could not be the least difference perceived, he, undiscovered by any, put them into the number of the Athenian virgins designated for Crete. At his return, he and these two youths led up a solemn procession, in the same habit that is now worn by those who carry the vine-branches. Those branches they carry in honor of Dionysos and Ariadne, for the sake of their story before related; or rather because they happened to return in autumn, the time of gathering the grapes.

“The women, whom they call Deipnopherai, or supper-carriers, are taken into these ceremonies, and assist at the sacrifice, in remembrance and imitation of the mothers of the young men and virgins upon whom the lot fell, for thus they ran about bringing bread and meat to their children; and because the women then told their sons and daughters many tales and stories, to comfort and encourage them under the danger they were going upon, it has still continued a custom that at this feast old fables and tales should be told. There was then a place chosen out, and a temple erected in it to Theseos, and those families out of whom the tribute of the youth was gathered were appointed to pay tax to the temple for sacrifices to him. And the house of the Phytalidai had the overseeing of these sacrifices, Theseos doing them that honor in recompense of their former hospitality.

Wild Dionysus Festivals

To pay their respect to Dionysus, the citizens of Athens, and other city-states, held a winter-time festival in which a large phallus was erected and displayed. After competitions were held to see who could empty their jug of wine the quickest, a procession from the sea to the city was held with flute players, garland bearers and honored citizens dressed as satyrs and maenads (nymphs), which were often paired together. At the end of the procession a bull was sacrificed symbolizing the fertility god's marriage to the queen of the city. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,"]

The word “maenad” is derived from the same root that gave us the words “manic” and “madness”. Maenads were subjects of numerous vase paintings. Like Dionysus himself they often depicted with a crown of iv and fawn skins draped over one shoulder. To express the speed and wildness of their movement the figures in the vase images had flying tresses and cocked back head. Their limbs were often in awkward positions, suggesting drunkenness.

The main purveyors of the Dionysus fertility cult "These drunken devotees of Dionysus," wrote Boorstin, "filled with their god, felt no pain or fatigue, for they possessed the powers of the god himself. And they enjoyed one another to the rhythm of drum and pipe. At the climax of their mad dances the maenads, with their bare hands would tear apart some little animal that they had nourished at their breast. Then, as Euripides observed, they would enjoy 'the banquet of raw flesh.' On some occasions, it was said, they tore apart a tender child as if it were a fawn'"μ

One time the maenads got so involved in what they were doing they had to be rescued from a snow storm in which they were found dancing in clothes frozen solid. On another occasion a government official that forbade the worship of Dionysus was bewitched into dressing up like a maenad and enticed into one of their orgies. When the maenads discovered him, he was torn to pieces until only a severed head remained."

It is not totally clear whether the maenad dances were based purely on mythology and were acted out by festival goers or whether there were really episodes of mass hysteria, triggered perhaps by disease and pent up frustration by women living in a male'dominate society. On at least one occasion these dances were banned and an effort was made to chancel the energy into something else such as poetry reading contests.

See Separate Article: DIONYSUS CULT: MAENADS, MYSTERIES, THEATER AND WILD FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Festivals for Women

There were two major festival for Athenian women every year: 1_ The Thesmophoria promoted fertility and honored Demeter and Persephone with piglet sacrifices and the offering of mass-produced statues of the goddess to receive her blessing; and 2) the Adonia, honoring Adonis, Aphrodite's lover Adonis. The later was a riotous festival in which lovers had openly licentious affairs and seeds were planting to mark the beginning of the planting season.

During Thesmophoria, women and men who required to abstain from sex and fast for three days. Women erected bowers made of branches and sat there during their fast. On the third day they carried serpent-shaped images thought to have magical powers and entered caves to claim decayed bodied of piglets left the previous years. Pigs were sacred animals to Demeter. The piglet remains were laid on an Thesmphoria altar with offerings, launching a party with feasting, dancing and praying. This rite also featured little girls dressed up as bears.

Thesmophoria was held in Pyanepsion (October) and lasted five days. Women that participated had to undergo a solemn preparation of nine days, during which they kept apart from their husbands, and purified themselves in various ways. After this they went to Halimus, the scene of the Thesmophoria, not in a long procession, but in small groups and at night-time. The comic side of the Demeter festivals was visible here also: those who went alone met each other on the way, and demanded and gave tokens of recognition in jest, amid much laughter, which became excessive if, as sometimes happened, a man fell into their hands. At Halimus, in the sanctuary of the Thesmophoria, the mysteries took place by night; the day was occupied with purifying baths in the sea, and playing and dancing on the shore. After this had gone on for a day or a day and a half, the women set out again for Athens, this time in a long procession, carrying the laws of Demeter, the Thesmoi whence the festival took its name, in caskets on the head of sacred women, and the festival was then continued at Athens, either in the Thesmophorion of the town or in that of Peiraeus. . [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

This further celebration occupied two days, besides the day of return; first came the day of “fasting,” so-called because on this day the women sat in deep mourning on the ground and took no food, probably singing dirges and observing other customs common in case of a death; they also sacrificed swine to the infernal gods. The third day (καλλιγενεία) bore a more cheerful character. Its name, signifying “the birth of fair children,” seems to refer to Demeter, who was assumed to be appeased and who gave the blessing of fair children to women. This day was occupied with sacrifices, dances, and merry games, of which we know very little. At all these festivals the presence of men was most sternly forbidden; only those women who were full citizens might take part, and probably none who were unmarried.

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “Adjoining the temple of Athena is the temple of Pandrosus, the only one of the sisters to be faithful to the trust. I was much amazed at something which is not generally known, and so I will describe the circumstances. Two maidens dwell not far from the temple of Athena Polias, called by the Athenians Bearers of the Sacred Offerings. For a time they live with the goddess, but when the festival comes round they perform at night the following rites. Having placed on their heads what the priestess of Athena gives them to carry — neither she who gives nor they who carry have any knowledge what it is — the maidens descend by the natural underground passage that goes across the adjacent precincts, within the city, of Aphrodite in the Gardens. They leave down below what they carry and receive something else which they bring back covered up. These maidens they henceforth let go free, and take up to the Acropolis others in their place. By the temple of Athena is .... an old woman about a cubit high, the inscription calling her a handmaid of Lysimache, and large bronze figures of men facing each other for a fight, one of whom they call Erechtheus, the other Eumolpus; and yet those Athenians who are acquainted with antiquity must surely know that this victim of Erechtheus was Immaradus, the son of Eumolpus. On the pedestal are also statues of Theaenetus, who was seer to Tolmides, and of Tolmides himself, who when in command of the Athenian fleet inflicted severe damage upon the enemy, especially upon the Peloponnesians.” [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

Dionysus procession

Demeter Procession in Hermione

On a Demter procession, in Hermione, a coastal town in Argolis in the Peloponnese, Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book II: Cornith: “The object most worthy of mention is a sanctuary of Demeter on Pron. This sanctuary is said by the Hermionians to have been founded by Clymenus, son of Phoroneus, and Chthonia, sister of Clymenus. But the Argive account is that when Demeter came to Argolis, while Atheras and Mysius afforded hospitality to the goddess, Colontas neither received her into his home nor paid her any other mark of respect. His daughter Chthoia disapproved of this conduct. They say that Colontas was punished by being burnt up along with his house, while Chthonia was brought to Hermion by Demeter, and made the sanctuary for the Hermionians. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“At any rate, the goddess herself is called Chthonia, and Chthonia is the name of the festival they hold in the summer of every year. The manner of it is this. The procession is headed by the priests of the gods and by all those who hold the annual magistracies; these are followed by both men and women. It is now a custom that some who are still children should honor the goddess in the procession. These are dressed in white, and wear wreaths upon their heads. Their wreaths are woven of the flower called by the natives cosmosandalon, which, from its size and color, seems to me to be an iris; it even has inscribed upon it the same letters of mourning.

“Those who form the procession are followed by men leading from the herd a full-grown cow, fastened with ropes, and still untamed and frisky. Having driven the cow to the temple, some loose her from the ropes that she may rush into the sanctuary, others, who hitherto have been holding the doors open, when they see the cow within the temple, close the doors. [2.35.7] Four old women, left behind inside, are they who dispatch the cow. Whichever gets the chance cuts the throat of the cow with a sickle. Afterwards the doors are opened, and those who are appointed drive up a second cow, and a third after that, and yet a fourth. All are dispatched in the same way by the old women, and the sacrifice has yet another strange feature. On whichever of her sides the first cow falls, all the others must fall on the same.[2.35.8] Such is the manner in which the sacrifice is performed by the Hermionians. Before the temple stand a few statues of the women who have served Demeter as her priestess, and on passing inside you see seats on which the old women wait for the cows to be driven in one by one, and images, of no great age, of Athena and Demeter. But the thing itself that they worship more than all else, I never saw, nor yet has any other man, whether stranger or Hermionian. The old women may keep their knowledge of its nature to themselves.”

Hercules Festival in Sicyon

On a festival in Sicyon, a city-state situated in the northern Peloponnesus between Corinth and Achaea, Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece” Book II: Corinth (A.D. 160): “In the gymnasium not far from the market-place is dedicated a stone Heracles made by Scopas.1 There is also in another place a sanctuary of Heracles. The whole of the enclosure here they name Paedize; in the middle of the enclosure is the sanctuary, and in it is an old wooden figure carved by Laphaes the Phliasian. I will now describe the ritual at the festival. The story is that on coming to the Sicyonian land Phaestus found the people giving offerings to Heracles as to a hero. Phaestus then refused to do anything of the kind, but insisted on sacrificing to him as to a god. Even at the present day the Sicyonians, after slaying a lamb and burning the thighs upon the altar, eat some of the meat as part of a victim given to a god, while the rest they offer as to a hero. The first day of the festival in honor of Heracles they name . . . ; the second they call Heraclea. From here is a way to a sanctuary of Asclepius. On passing into the enclosure you see on the left a building with two rooms. In the outer room lies a figure of Sleep, of which nothing remains now except the head. The inner room is given over to the Carnean Apollo; into it none may enter except the priests. In the portico lies a huge bone of a sea-monster, and after it an image of the Dream-god and Sleep, surnamed Epidotes (Bountiful), lulling to sleep a lion. Within the sanctuary on either side of the entrance is an image, on the one hand Pan seated, on the other Artemis standing. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

Herakles at a symposium

“When you have entered you see the god, a beardless figure of gold and ivory made by Calamis.1 He holds a staff in one hand, and a cone of the cultivated pine in the other. The Sicyonians say that the god was carried to them from Epidaurus on a carriage drawn by two mules, that he was in the likeness of a serpent, and that he was brought by Nicagora of Sicyon, the mother of Agasicles and the wife of Echetimus. Here are small figures hanging from the roof. She who is on the serpent they say is Aristodama, the mother of Aratus, whom they hold to be a son of Asclepius. Such are the noteworthy things that this enclosure presented to me, and opposite is another enclosure, sacred to Aphrodite. The first thing inside is a statue of Antiope. They say that her sons were Sicyonians, and because of them the Sicyonians will have it that Antiope herself is related to themselves. After this is the sanctuary of Aphrodite, into which enter only a female verger, who after her appointment may not have intercourse with a man, and a virgin, called the Bath-bearer, holding her sacred office for a year. All others are wont to behold the goddess from the entrance, and to pray from that place. The image, which is seated, was made by the Sicyonian Canachus, who also fashioned the Apollo at Didyma of the Milesians, and the Ismenian Apollo for the Thebans. It is made of gold and ivory, having on its head a polos,1 and carrying in one hand a poppy and in the other an apple. They offer the thighs of the victims, excepting pigs; the other parts they burn for the goddess with juniper wood, but as the thighs are burning they add to the offering a leaf of the paideros.

“This is a plant in the open parts of the enclosure, and it grows nowhere else either in Sicyonia or in any other land. Its leaves are smaller than those of the esculent oak, but larger than those of the holm; the shape is similar to that of the oak-leaf. One side is of a dark color, the other is white. You might best compare the color to that of white-poplar leaves. Ascending from here to the gymnasium you see in the right a sanctuary of Artemis Pheraea. It is said that the wooden image was brought from Pherae. This gymnasium was built for the Sicyonians by Cleinias, and they still train the youths here. White marble images are here, an Artemis wrought only to the waist, and a Heracles whose lower parts are similar to the square Hermae.”

Delphic Festival and Pythian Games

The games performed at Delphi in honor of Pythian Apollo bore the name of the Great Pythia, to distinguish them from the Lesser Pythia, held every year at Delphi, and also from the festival of the same name celebrated in other places. This festival, which at first was held every eight years, had been changed to a quadrennial one after the beginning of the 6th century B.C.; it lasted several days, and gradually many additions were made to the original contests. At first the musical competition, which comprised kithara and flute playing, was the only one; in later times, too, it was the principal part of the festival, but after the example of the Olympian games, gymnastic and equestrian contests were also added. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

We know but little of the athletic contests which gradually found a place in the Pythian games. In essentials they were the same as those at Olympia, but the double course and the long course for boys were also added, while at Olympia these two contests were only open to men. The order of events, too, was different; the competitors were classed according to age, and each class, after completing its own contests, was able to rest while the others went through the same exercise, so that these intervals for rest enabled the boys to perform greater feats of running than they could at Olympia, where they had to enter for all their contests before the men’s turn came at all.

To the usual gymnastic sports were afterwards added the race in full panoply and the pancration for boys. Equestrian competitions were early introduced; racing with full-grown horses, with four-horse chariots, and afterwards with two-horse chariots; when colts were introduced at Olympia the example was also followed at Delphi: probably the events followed in such a way that the musical contest was connected with the acts of worship, and was followed by the gymnastic, and this by the equestrian contests. The gymnastic sports were held, at the time of Pindar, in the neighbourhood of the ruined city Cirrha, south of the mouth of the Pleistos; afterwards the Delphic Stadion was to the north-west of the city, while the driving and riding races took place in the old Stadion near the ruined city of Cirrha. In later times there was also a theatre for the performance of the musical contests.

See Delphic Festival and Pythian Games Under ORACLE IN DELPHI: PYTHIA, TEMPLE, VAPORS europe.factsanddetails.com

Great Mysteries Festival

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In classical antiquity, the earliest and most celebrated mysteries were the Eleusinian. At Eleusis, the worship of the agricultural deities Demeter and her daughter Persephone, also known as Kore, was based on the growth cycles of nature. Athenians believed they were the first to receive the gift of grain cultivation from Demeter. [Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

“During the Great Eleusinia, the public aspect of which culminated in the grand procession from the center of Athens to Eleusis along the Sacred Way, the actions and experiences of the initiates mirrored those of the two goddesses in the sacred drama (drama mystikon). In the early sixth century B.C., the "Queen of the Underworld" persona of Kore was introduced and a nocturnal initiation rite called katabasis was added to the festival: a simulated descent to Hades and ritual search for Persephone. Before the entrance to the Telesterion, the central hall of the sanctuary where the secret rites were performed, priestly personnel holding torches met up with the initiates, who until then were wandering in the dark. At the Eleusinian mysteries, the tension between public and private, conspicuous and secret was inherent in the double nature of the cult. Unlike city-state (polis) religion, participation was restricted to individuals who chose to be initiated, to become mystai. At the same time, it was far more inclusive, being open not only to Athenian male citizens, but to non-Athenians, women, and slaves.” \^/

Eleusinian mysteries

The Lesser Mysteries: Athenian 'flower-month' Anthesterion (February/March) — with 12th Pithoigia 'opening the jars', 13th Choes 'wine amphorae' and 14th Chytrai — was held at Agrai, in Athens, on the south east side of the Ilissos stream, just outside the old walls, where there was a shrine for Demeter (Metroon) and for Artemis. It was said the maiden Oreithyeia was abducted here by Boreas ('North Wind': Death/cold) and ravished. Her companion was Pharmakeia ('user-of-drugs'). [Plato Phaedrus 229c] [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class ++]

Greater Mysteries:: Athenian 'bull-running' month Boedromion (September-October). On the 13th and 14th Boed., young aristocratic Athenian Ephebes (teens engaged in military training) escorted the 'sacred things' from Eleusis to Athens. The ‘sacred things’ were brought to the Eleusinion, at the west foot of the Acropolis. Their arrival was then reported to the priestess of Athena Polias (City-Athena). The first four days of the festival took place in Athens (15th to 18th): 15th Agrimos ('Gathering'), 16th 'Seaward, Initiates', 17th 'Hither the victims', 18th Epidauria (at Athens), 19th March to Eleusis,20th Initiation, 21st Plemochoiai ++

The festival was supervised by the Athenian magistrate, the Basileus ('King'), with two assistants from the Athenian Citizen body and a representative of the Clan Eumolpidai and Clan Kerykes. Initiates had to bathe in the sea and sacrifice a pig to Demeter. The 20-kilometer Procession to Eleusis (14 miles) was led by statue of Iacchos (Bacchus). Participants wore crowns of myrtle on their heads and carried bundles of leaves bound with bacchoi (rings).

At night inside a small building called the A naktoron ('King's house' wanax) in the Telesterion ('Hall of Initiation') in Eleusis, the sacred things were placed in baskets (kistai) were 'shown' by the Hierophant. Epopteia ('Beholding') was an optional festival held the year following for Greater Mysteries festival. The Mystai (initiates of the previous year's ceremony) A fresh-cut wheat stalk was 'shown'.” ++

See Separate Article: GREAT MYSTERIES FESTIVAL europe.factsanddetails.com

Panathenaea — the Great Athenian Festival

The greatest festival of the Athenians, the Panathenaea, was celebrated in the first month of the Athenian calendar, Hekatombaeon (probably our July). During the Panathanaic procession citozen dressed in woven robes like the one believed to be worn by Athena and marched through the city to the Acropolis. The procession was led by the Athenian cavalry and included priests, sacrificial animals, chariots, athletes, and maidens. One of the marque events was the apobates , in which contestants in full armor leapt on and off moving chariots.

We must distinguish between the lesser and the greater Panathenaea; the former was celebrated every year; the latter, introduced by Peisistratus, every four years; the real difference was that, at the greater Panathenaea the contests were more splendid and probably lasted a longer time. The festival was held in honor of the patron goddess in the ancient temple of Athene Polias; it consisted of sacrifices and competitions, equestrian, gymnastic, and also musical. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

We have only a general notion of the order of the festivities. They began with the contests, which lasted several days, taking the musical contest first, which was followed by the gymnastic, and this again by the equestrian. With these were probably connected the Pyrrhic dance and the muster of men. Then came the chief day of all, the glory of the festival, introduced the evening before by a festivity combined with a torch-race, and lasting far into the night (παννυχίς).

Contests at the Panathenaea

The oldest musical contest was a competition between rhapsodists, perhaps introduced by Peisistratus. The performances of the rhapsodists were probably chiefly concerned with the Homeric poems, which had been collected and edited at the command of Peisistratus, but we do not know in what way they contended for the prize; the place of recitation was the Odeon. Afterwards the Homeric rhapsodies fell into the background, when Pericles extended the musical contests by introducing kithara and flute playing and song. We learn from the inscriptions that songs with kithara accompaniment, as well as with flute accompaniment, were usual, and they also speak of cyclic choruses, that is, dithyrambs, sung by choruses while circling round the altar on which the sacrifice was burning. The prize for the musical contest was a gold wreath and some money.

To the festivities of the Panathenaea belonged also a performance of the Pyrrhic war dance which originated at Sparta, and was probably introduced at Athens at the time of Solon and Peisistratus. In later times they distinguished three kinds, according to age. The various classes, clad in magnificent armour, combined together in bands and performed a dance to the music of the flute, which partook of the double nature of choregraphic and military movements. A still extant relief from the Acropolis, set up by a choragus who had won the prize (rich citizens undertook the equipment of the Pyrrhic choruses as a public service or liturgy), presents a number of youthful dancers performing a measured dance in light helmets, and holding their shield in their left hand, but without any clothing; they are in two divisions; the choragus stands superintending them in a long chiton (as festive garment) and himation. We do not know how the victory of a Pyrrhic chorus was decided. The prize of victory was an ox.

Another contest peculiar to the Panathenaea was a muster of men (εὐανδρία). Like the dramatic representations, the torch-race, and the Pyrrhic dance, this was a liturgy, that is, a voluntary service performed by a rich citizen. It was his duty to select the handsomest and strongest men of his tribe, to clothe and equip them, and present them at the festival; that tribe which, in the opinion of the judges, made the best impression, received the prize. This curious custom originated after the expulsion of the Peisistratidae, since they would not have been permitted, during the tyranny, to bring forward the armed citizens in this manner. Another liturgy was the torch-race (λαμπαδοφορία), which was superintended by the gymnasiarchs; the victor in this contest received a water-jar. The contests of the Panathenaea were concluded by a regatta, which took place at the Peiraeus. Here, again, it was not individuals, but tribes, that competed for the prize, which was not inconsiderable, since the victorious tribe received 300 drachmae, and money for a festive banquet.

The expenses of these various contests, if they did not happen to be voluntary services, were defrayed from the treasury of Athene Polias; the sacrifices, in particular the hecatomb offered to the goddess at the greater Panathenaea, were provided by the superintendents of sacrifice (ἱεροποιοί), appointed as the ten representatives of the ten tribes, but there were sometimes special subscriptions for the purpose, and, at the great festivals at any rate, the Attic client cities sent their contributions to the sacrifices, apparently each one cow and two sheep. The hecatomb was offered on the chief day of the feast; another sacrifice was performed to Athene-Hygeia, and a third on the Areopagus, but we do not know when these took place, nor whether they were also offered at the lesser Panathenaea.

See Sports Contests at the Panathenaea Under ANCIENT GREEK SPORTS FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

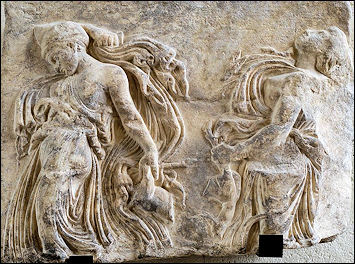

Processions at the Panathenaea

At sunrise began the great procession which was peculiar to the greater Panathenaea. Here the goddess received her splendid robe, which was renewed every four years, and artistically worked by the Attic women and maidens, so as to represent the battle of the gods and giants. This procession, of which a wonderfully idealised representation has come down to us in the friezes of the Cella of the Parthenon, combined all the chief splendour and glory of Athens, all the proud youth and fair beauty of women. In it marched priests and prophets, archons, and the treasurers of Athene, the superintendents of sacrifice, generals, envoys from the Attic colonies, with their dedicatory offerings, and other delegates sent to the feast. Behind these dignified men followed beautiful maidens, carrying sacrificial vessels, censers, etc.; then came the resident foreigners (μέτοικοι), with flat dishes filled with honey-cakes, fruits, and other sacrificial offerings, and jars containing the wine required for the sacrifices; their daughters carried sunshades and seats for the daughters of Attic citizens. Next came the numerous herds of cows and sheep for the sacrifices, accompanied by drovers. These were followed by the Attic citizens, venerable old men and men in the prime of life, carrying their knotty sticks and olive branches in their hands; then came the four-horse chariots, which had entered for the contests of the previous days. The greater part of the procession was taken up by the cavalry, in which appeared the citizens who served on horseback in the army, as well as other owners of fine horses; the fondness for horse-rearing peculiar to Attica made this part of the procession especially large and splendid. There were also the heavy-armed infantry under the command of their officers, and the musicians, who played during the march on their instruments — flutes and kitharas; of course, the victors in the various competitions took part in the procession, though probably each walked with the members of his own tribe. The most conspicuous place was occupied by the robe of the goddess, which, at any rate after the beginning of the fourth century, was suspended like a sail on the mast of a ship, running on rollers, and spread out in such a way that all might admire the splendid workmanship.

This endless procession moved from the Kerameikos to the market-place, then eastwards to the Eleusinion, north of the Acropolis, and round this to the western ascent of the citadel, where the ship halted, and the robe was taken off in order to be carried in procession to the temple of Athene Polias, the Erechthaeum. Here the hecatomb was offered on the great altar in front of the temple, as well as the sacrifices of the Attic clients. A plentiful banquet concluded this chief day of the festival, for the meat sacrificed was divided among the people, being distributed among all the demes separately, who specially told off a number of members to receive their share. The meals took place also according to demes. The after celebration at the Peiraeus consisted in the regatta already mentioned. We cannot tell how long the whole festival of the greater Panathenaea lasted; opinions vary between six and nine days, according as a longer or shorter period is assumed for the various competitions. The general direction of the procession and the sacrifices, as well as of the night festivity, was under the control and superintendence of the annual superintendents of sacrifice; while ten judges (ἀθλοθέται), appointed for a period of four years, undertook the direction of the contests.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024