ROMAN FUNERALS

funeral stele of a gladiator from Ephesus

The word for funeral is derived from funus, the Latin word for "torch." The Romans believed a flaming torch guided the deceased to the afterlife and scared away evil spirits. The Romans practiced cremation and inhumation. In the early Roman era burials took place mostly at night. Later they were conducted during the day but were sometimes performed under torchlight as a reminder of the night time burials. In most cases the dead were buried or burned outside the city walls for both sanitary reasons and religious reasons. This is why tombs, catacombs and cemeteries are often found outside Roman city ruins.

The Romans put a lot of care into funerals both as a way of helping the deceased in the next life and displaying their social position. The type of funeral an individual had depended on their status and wealth. The rites and services depended on whether the deceased was a soldier, shopkeeper or aristocrat, with the most elaborate services reserved for the emperors and their families. The person in charge of arranging the funeral was often designated in the will.

Because funerals were so expensive, soldiers and citizens from less than noble families joined burial clubs that paid for services with deductions taken out a person's pay. Children who died were often placed in a pot and buried in the family garden. For the rich, there was sometimes so much pomp that laws were passed to prevent wasteful spending. wasteful spending.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Death and Burial in the Roman World” by J. M. C. Toynbee (1996) Amazon.com;

“Roman Death: The Dying and the Dead in Ancient Rome” by Valerie M. Hope (2009) Amazon.com;

“Death in Ancient Rome” by Catharine Edwards (2015) Amazon.com;

“Populus: Living and Dying in Ancient Rome” by Guy de la Bédoyère (2024) Amazon.com;

“Of Noble Roman Funerals” by Michael Boyajian (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Roman Afterlife: Di Manes, Belief, and the Cult of the Dead” by Charles W. King (2020) Amazon.com;

“After Life in Roman Paganism: The Funeral Rites, Gods and Afterlife of Ancient Rome”

by Franz Valery Marie Cumont (1922) Amazon.com;

“Death as a Process: The Archaeology of the Roman Funeral” by John Pearce and Jake Weekes (2017) Amazon.com;

“Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome” by Donald G. Kyle (2012) Amazon.com;

“Death, Burial and Rebirth in the Religions of Antiquity” by Jon Davies (1999) Amazon.com;

“Roman Tombs and the Art of Commemoration: Contextual Approaches to Funerary Customs in the Second Century CE” by Barbara E. Borg (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Catacombs: The History and Legacy of Ancient Rome’s Most Famous Burial Grounds” by Charles River Editors (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Catacombs” by Rev. James Spencer Northcote (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Art of the Roman Catacombs: Themes of Deliverance in the Age of Persecution”

by Gregory S Athnos (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Christian Catacombs of Rome: History, Decoration, Inscriptions”

by Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai, Fabrizio Bisconti, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Early Greek Concept of the Soul” by Jan Bremmer (1983); Amazon.com;

Romans View on the Importance of a Food Funeral and Burial

The Romans’ view of the future life explains the importance they attached to the ceremonial burial of the dead. The soul, they thought, could find rest only when the body had been duly laid in the grave; until this was done it haunted the home, unhappy itself and bringing unhappiness to others. To perform funeral offices was a solemn religious duty, devolving upon the surviving members of the family; the Latin expression for such rites, iusta facere, shows that these marks of respect were looked upon as the right of the dead. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion:At the end of life, the Feriae Denecales (denecales or deni-, perhaps from de nece, "following death") took place. The purpose was to purify the family in mourning, for the deceased was regarded as having defiled his or her family, which thus became funesta (defiled by death). To this end, a novemdiale sacrum was offered on the ninth day after burial. As for the deceased, the body, or a finger thereof kept aside (os resectum) in the case of cremation, was buried in a place that become inviolable (religiosus). The burial was indispensable in order to assure the repose of the deceased, who from then on was venerated among the di parentes (later the di manes). If there were no burial, the deceased risked becoming one of the mischievous spirits, the lemures, which the father of the family would expel at midnight on the Lemuria of May 9, 11, and 13.[Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

In the case of a body lost at sea, or for any other reason unrecovered, the ceremonies were just as piously performed; an empty tomb (cenotaphium) was erected sometimes in honor of the dead. Such rites the Roman was bound to perform carefully, if he came anywhere upon the unburied corpse of a citizen, because all men were members of the greater family of the Commonwealth. In this case the scattering of three handfuls of dust over the body was sufficient for ceremonial burial and the happiness of the troubled spirit, if for any reason the body could not actually be interred.” |+|

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Roman Cremations and Burials

funeral carpentum

Cremations were favored over burials. They usually took place at a special location outside the city walls. The funeral pyre was made of wood mixed with papyrus to help it burn. The body was placed on it with eyes open. The cremations were usually carried out by professionals called ustores.

Offerings and possessions, and sometimes even pets of the dead, were burned along with the body presumably to accompany the deceased on the journey to the afterlife. The ashes were drenched in wine placed in a special receptacle: an urn, jar, pot, or chest. These were placed in a niche in their final resting place: a columbaria (repository for ashes), house, chamber, tomb or under a tumulus or gravestone.

Burial was the way of disposing of the dead practiced most anciently by the Romans, and, even after cremation came into very general use, it was ceremonially necessary that some small part of the remains, usually the bone of a finger, should be buried in the earth. Burning was practiced before the time of the Twelve Tables (traditional date, 451 B.C.), for it is mentioned in them together with burial, but we do not know how long before. Hygienic reasons had probably something to do with its general adoption; this implies, of course, cities of considerable size. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

By the time of Augustus it was all but universal, but even in Rome the practice of burial was never entirely discontinued, for cremation was too costly for the very poorest classes, and some of the wealthiest and most aristocratic families held fast to the more ancient custom. The Cornelii, for example, always buried their dead until the great dictator, Cornelius Sulla, required his body to be burned for fear that his bones might be disinterred and dishonored by his enemies, as he had dishonored those of Marius. Children less than forty days old were always buried, and so, too, as a rule, were slaves whose funeral expenses were paid by their masters. After the introduction of Christianity burial came again to be the prevailing use, partly because of the increased expense of burning.” |+|

Etruscan Burials

The Etruscans preceded the Romans as the dominant group in Italy. The Roman custom of displaying the body of the dead, ritual lamentations and hired mourners appears to have originated with the Etruscans. Roman funerary art and architecture and concepts of the afterlife also seem to have also been shaped by the Etruscans.

Etruscans practiced cremation and inhumation. The funeral pyres were often placed near the tomb and offerings and possessions of the dead were often burned along with the body. The remains were placed in terra cotta jars and pots or decorated alabaster and terra cotta chests with effigies or reliefs on the top. These were placed in cylindrical well tombs dug in the rock or earth. A variety of food stuffs and grave goods were buried with the dead. An urn with cremation remains of women found in a tomb in Chiusi is topped by a head and has arms coming out of the handles.

Early inhumations have been found in plain wood sarcophagi in shallow trench graves. Later ones, starting around the 7th century B.C., were placed in more elaborate sarcophagi made from a variety of materials. These were placed in chamber tombs, both above ground and below ground, with a variety of food stuffs and grave goods. Often the dead were placed on special funerary beds, which could be both real beds with pillows or fake ones carved of stone.

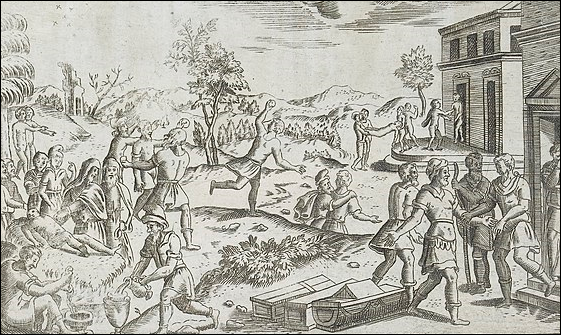

from the rare book Roman Funeral Customs

Roman Funeral Ceremonies and Feasts

The detailed accounts of funeral ceremonies that have come down to us relate almost exclusively to those of persons of high position, and the information gleaned from other sources is so scattered that there is great danger of confusing usages of widely different times. It is quite certain, however, that, at all times, very young children were buried simply and quietly (funus acerbum), that no ceremonies at all attended the burial of slaves when conducted by their masters (nothing is known of the forms used by the burial societies), and that citizens of the lowest class were laid to rest without public parade (funus plebeium). It is also known that burials took place by night except during the last century of the Republic and the first two centuries of the Empire, and it is natural to suppose that, even in the case of persons of high position, there was ordinarily much less of pomp and parade than on occasions that the Roman writers thought it worth while to describe. This was found true in the matter of wedding festivities. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) ]

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “When any illustrious person dies, he is carried in procession with the rest of the funeral pomp, to the rostra in the forum; sometimes placed conspicuous in an upright posture; and sometimes, though less frequently, reclined. And while the people are all standing round, his son, if he has left one of sufficient age, and who is then at Rome, or, if otherwise, some person of his kindred, ascends the rostra, and extols the virtues of the deceased, and the great deeds that were performed by him in his life. By this discourse, which recalls his past actions to remembrance, and places them in open view before all the multitude, not those alone who were sharers in his victories, but even the rest who bore no part in his exploits, are moved to such sympathy of sorrow, that the accident seems rather to be a public misfortune, than a private loss. He is then buried with the usual rites; and afterwards an image, which both in features and complexion expresses an exact resemblance of his face, is set up in the most conspicuous part of the house, inclosed in a shrine of wood. Upon solemn festivals, these images are uncovered, and adorned with the greatest care. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

“And when any other person of the same family dies, they are carried also in the funeral procession, with a body added to the bust, that the representation may be just, even with regard to size. They are dressed likewise in the habits that belong to the ranks which they severally filled when they were alive. If they were consuls or praetors, in a gown bordered with purple: if censors, in a purple robe: and if they triumphed, or obtained any similar honor, in a vest embroidered with gold. Thus appeared, they are drawn along in chariots preceded by the rods and axes, and other ensigns of their former dignity. And when they arrive at the forum, they are all seated upon chairs of ivory; and there exhibit the noblest objects that can be offered to youthful mind, warmed with the love of virtue and of glory. For who can behold without emotion the forms of so many illustrious men, thus living, as it were, and breathing together in his presence? Or what spectacle can be conceived more great and striking? The person also that is appointed to harangue, when he has exhausted all the praises of the deceased, turns his discourse to the rest, whose images are before him; and, beginning with the most ancient of them, recounts the fortunes and the exploits of every one in turn. By this method, which renews continually the remembrance of men celebrated for their virtue, the fame of every great and noble action become immortal.

from the rare book Roman Funeral Customs

And the glory of those, by whose services their country has been benefited, is rendered familiar to the people, and delivered down to future times. But the chief advantage is, that by the hope of obtaining this honorable fame, which is reserved for virtue, the young men are animated to sustain all danger, in the cause of the common safety. For from hence it has happened, that many among the Romans have voluntarily engaged in single combat, in order to decide the fortune of an entire war. Many also have devoted themselves to inevitable death; some of them in battle, to save the lives of other citizens; and some in time of peace to rescue the whole state from destruction. Others again, who have been invested with the highest dignities have, in defiance of all law and customs, condemned their own sons to die; showing greater regard to the advantage of their country, than to the bonds of nature, and the closest ties of kindred.”

Funerals for the elite were often accompanied by lavish feasts that featured things like doves, chickens, figs, dates, and white almonds. People ate while incense burners filled with sweet-smelling pine cones burned. The feasts were often conducted as the deceased was laid to rest or on the ninth day after the funeral. At the feasts it was considered very important to set aside some food for the deceased (this was often later stolen and eaten by the hungry). Even after the official mourning period was over people often ate meals at the resting place of the deceased. There was a special holiday in February in which food offerings were made to the dead. Sometimes large sums of money were set aside and people were paid long after the deceased had died to provide food at their graves. The dead were often buried with eating utensils. Sometimes graves had pipes running to the surface for the delivery of libations.

Roman Funerary Rites and Ceremonies At the House

The family often gathered around a seriously ill person as they were dying so that one person could deliver a "last kiss," an effort to capture the final breath and free the soul of the dying person. The eyes were then shut, lamentations with the deceased's name were chanted and the body was washed, anointed and dressed. A wreath was placed on the head and a coin was placed in the mouth of the deceased so they could pay Charon the ferryman to get across the river Styx in the Underworld.

When the Roman died at home surrounded by his family, it was the duty of his oldest son to bend over the body and call him by name, as if with the hope of recalling him to life. The formal performance of this act (conclamatio) he announced immediately with the words conclamatum est. The eyes of the dead were then closed, the body was washed with warm water and anointed, the limbs were straightened, and, if the deceased had held a curule office, a wax impression of his features was taken. The body was then dressed in the toga with all the insignia of rank that the dead had been entitled to wear in life, and was placed upon the funeral couch (lectus funebris) in the atrium, with the feet to the door, to lie in state until the time of the funeral. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

from Roman Funeral Customs

“The couch was surrounded with flowers, and incense was burned about it. Before the door of the house were set branches of pine or cypress as a warning that the house was polluted by death. The simple offices that have been described were performed in humble life by the relatives and slaves, in other cases by professional undertakers (libitinarii), who also embalmed the body and superintended all the rest of the ceremonies. Reference is made occasionally to the kissing of the dying person as he breathed his last, as if this last breath was to be caught in the mouth of the living; and in very early and very late times it was undoubtedly the custom to put a small coin between the teeth of the dead with which to pay his passage across the Styx in Charon’s boat. Neither of these formalities seems to have obtained generally in classical times.” |+|

Funeral Procession and Oration in Ancient Rome

The body was then placed on display for one to seven days. After this time was up the body was carried in a procession to the final resting place. Those without money were carried on a cheap bier. The wealthy were taken in elaborate palanquins carried by four to eight male relatives. Sometimes it was followed by musicians and professional mourners. Sometimes people wore masks with the deceased's likeness. Funerals for Roman nobles consisted of a procession to the forum, followed by a eulogy and burial rites. Elaborate funerals featured dirges and panegyrics (speeches praising the dead).

The funeral procession of the ordinary citizen was simple enough. Notice was given to neighbors and friends. Surrounded by them and by the family, carried on the shoulders of the sons or other near relatives, with perhaps a band of musicians in the lead, the body was borne to the tomb. The procession of one of the mighty, on the other hand, was marshaled with all possible display and ostentation. It occurred as soon after death as the necessary preparations could be made, as there was no fixed intervening time. Notice was given by a public crier in the ancient words of style: Ollus Quiris leto datus. Exsequias, quibus est commodum, ire iam tempus est. Ollus ex aedibus effertur.2 Questions of order and precedence were settled by an undertaker (designator). [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“At the head of the procession went a band of musicians, followed, at least occasionally, by persons singing dirges in praise of the dead, and by bands of buffoons and jesters, who made merry with the bystanders and imitated even the dead man himself. Then came the imposing part of the display. The wax masks of the dead man’s ancestors had been taken from their place in the alae and assumed by actors in the dress appropriate to the time and station of the worthies they represented. It must have seemed as if the ancient dead had returned to earth to guide their descendant to his place among them. Servius tells us that six hundred imagines were displayed at the funeral of the young Marcellus, the nephew of Augustus. Then followed the memorials of the great deeds of the deceased, if he had been a general, as in a triumphal procession, and then the dead man himself, carried with face uncovered on a lofty couch. Then came the family, including freedmen (especially those made free by the testament of their master) and slaves, and next the friends, all in mourning garb, and all freely giving expression to the emotion that we try to suppress on such occasions. Torchbearers attended the train, even by day, as a remembrance of the older custom of burial by night. |+|

from Roman Funeral Customs

The procession passed from the house directly to the place of interment, unless the deceased was a person of sufficient consequence to be honored by public authority with a funeral oration (laudatio) in the Forum. In this case the funeral couch was placed before the rostra, the men in the masks took their places on curule chairs around it, the general crowd was massed in a semicircle behind, and a son or other near relative delivered the address. It recited the virtues and achievements of the dead and recounted the history of the family to which he belonged. Like such addresses in more recent times it contained much that was false and more that was exaggerated. The honor of the laudatio was freely given in later times, especially to members of the Imperial family, including women. Under the Republic it was less common and more highly prized; so far as we know the only women so honored belonged to the gens Iulia. It will be remembered that it was Caesar’s address on the occasion of the funeral of his aunt, the widow of Marius, that pointed him out to the opponents of Sulla as a future leader. When the address in the Forum was not authorized, one was sometimes given more privately at the grave or at the house.” |+|

Roman Funerary Rites and Ceremonies At the Tomb

When the procession reached the place of burial, the proceedings varied according to the time, but all provided for the three things ceremonially necessary: the consecration of the resting place, the casting of earth upon the remains, and the purification of all polluted by the death. In ancient times the body, if buried, was lowered into the grave either upon the couch on which it had been brought to the spot, or in a coffin of burnt clay or stone. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“If the body was to be burned, a shallow grave was dug and filled with dry wood, upon which the couch and body were placed. The pile was then fired and, when wood and body had been consumed, earth was heaped over the ashes into a mound (tumulus). Such a grave in which the body was burned was called bustum, and was consecrated as a regular sepulcrum by the ceremonies mentioned below. In later times the body, if not to be burned, was placed in a sarcophagus already prepared in the tomb. |+|

“If the remains were to be burned, they were taken to the ustrina , which was not regarded as a part of the sepulcrum, and placed upon the pile of wood (rogus). Spices and perfumes were thrown upon them, together with gifts and tokens from the persons present. The pyre was then lighted with a torch by a relative, who kept his face averted during the act. After the fire had burned out, the embers were extinguished with water or wine and those present called a last farewell to the dead. The water of purification was then thrice sprinkled over those present, and all except the immediate family left the place. The ashes were then collected in a cloth to be dried, and the ceremonial bone, called os resectum, was buried. A sacrifice of a pig was then offered, by which the place of burial was made sacred ground, and food (silicernium) was eaten together by the mourners. They then returned to the house, which was purified by an offering to the Lares, and the funeral rites were over.” |+|

After the Roman dictator Sulla died in 78 B.C., the senate decreed him a public funeral, the most splendid that Rome had ever seen. His body was burned in the Campus Martius. Upon the monument which was erected to his memory were inscribed these words: “No friend ever did him a kindness, and no enemy a wrong, without being fully repaid.” [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

from Roman Funeral Customs

Funeral for the Roman Emperor

Describing the deification of Emperor Septimius Severus in A.D. 211, the Greek historian Herodian wrote: "It is a Roman custom to give divine status to those emperors who die with heirs to succeed them. This ceremony is called deification. Public mourning, with a mixture of festive and religious ritual, is proclaimed throughout the city, and the body of the dead emperor is buried in the normal way with a costly funeral.

"Then they make an exact wax replica of the man, which they put on a huge ivory bed strewn with gold-threaded coverings, raised high up in the entrance to the palace. This image, in the deathly palace, rests there like a sick man . . . the whole Senate sitting on the left, dressed in black, while on the right are all women who can claim special honors . . .This continues for seven days, during each of which doctors come and approach the bed, take a look at the supposed invalid and announce a daily deterioration in his condition."

“When at last the news is given that he is dead, the bier is raised on the shoulders of the noblest members of the Equestrian Order and selected young Senators, carried along the Sacred Way, and placed in the Forum Romanum . . . a chorus of children from the noblest and most respected families stands facing a body of women selected on merit. Each group sings hymns and songs."

“After this the bier is raised and carried outside the city walls to a square structure filled with firewood and covered with golden garments, ivory decorations and rich pictures. On top of the structure are five more structures that are progressively smaller. The whole thing was often five or six stories tall."

"When the bier has been taken to the second story and put inside, aromatic herbs and incense of every kind produced on earth, together with flowers, grasses and juices collected for their smell, are brought and poured in heaps . . . When the pile of aromatic material is very high and the whole space filled . . . The whole equestrian order rides round . . . Chariots also circle in the same formation, the charioteers dressed in purple and carrying images with the masks of famous Roman generals and emperors."

“The heir to the throne takes a brand and sets it to every building . All the spectators crowd in and add to the flame. Everything is very easily and readily consumed . . . From the highest and smallest story . . . an eagle is released and carried up into the sky with the flames. The Romans believe the bird bears the soul of the emperor from earth to heaven. Thereafter the dead emperor is worshipped with the rest of the gods."

A sculpted relief from the base of the column of the emperor Antoninus Pius, dated to A.D. 161, shows the apotheosis (transformation into gods) of Antoninus Pius and his wife Faustina. “They are shown by the portrait busts at the top of the frame, flanked by eagles - associated with imperial power and Jupiter- and were typically released during imperial funerals to represent the spirits of the deceased. Antoninus and Faustina are being carried into the heavens by a winged, heroically nude figure. The armoured female figure on the right is the goddess Roma, a divine personification of Rome, and the reclining figure to the left - with the obelisk - is probably a personification of the Field of Mars in Rome, where imperial funerals took place. |::|

See Caesar’s and Augustus's Funerals Under AFTER THE ASSASSINATION OF JULIUS CAESAR europe.factsanddetails.com and AUGUSTUS'S DEATH, LEGACY, WILL AND EFFORT TO PREPARE A SUCCESSOR europe.factsanddetails.com

from Roman Funeral Customs

After a Roman Funeral

When family members returned home after the funeral they underwent a purification ritual with fire and water. They placed a wax death mask of the deceased on a bust which in turn was placed in the most prominent place in the house. Later on the bust was placed on a shelf in the atrium with likenesses of other deceased relatives, all of whom were connected by colored lines that assembled them into a genealogical chart. During some festivals a crown of bay leaves was placed on the busts.

There was a nine day morning period. On the ninth day after the funeral special libations were poured over the grave. February was the last month of the year. The entire month was often devoted to purification and placation rituals oriented towards the dead. These were done to make the dead happy in the afterlife which in turn was supposed to bring about a good agricultural season. Rituals like those on the Day of the Dead today were performed at graves. Animals were sacrificed to ensure a good planting season.

With the day of the burial or burning of the remains began the “Nine Days of Sorrow,” solemnly observed by the immediate family. Some time during this period, when the ashes had had time to dry thoroughly, members of the family went privately to the ustrina, removed the ashes from the cloth, put them in an olla of earthenware, glass, alabaster, bronze, or other material, and with bare feet and loosened girdles carried them into the sepulcrum. At the end of the nine days the sacrificium novendiale was offered to the dead and the cena novendialis took place at the house. On this day, too, the heirs formally entered upon their inheritance and the funeral games were originally given. The period of mourning, however, was not concluded on the ninth day. For husband or wife, ascendants, and grown descendants mourning was worn for ten months, the ancient year, for other adult relatives, eight months, for children between the ages of three and ten years, for as many months as they were years old. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

Remembering the Dead in Ancient Rome

The memory of the dead was kept alive by regularly recurring “days of obligation” of both public and private character. To the former belong the Parentalia, or dies parentales, lasting from the thirteenth to the twenty-first of February, the final day being especially distinguished as the Feralia. To the latter belong the annual celebration of the birthday (or the burial day) of the person commemorated, and the festivals of violets and roses (Violaria, Rosaria), about the end of March and May respectively, when violets and roses were distributed among the relatives and laid upon the graves or heaped over the urns. On all these occasions offerings were made in the temples to the gods and at the tombs to the manes of the dead, and the lamps were lighted in the tombs, and at the tombs the relatives feasted together and offered food to their dead. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: During the Dies Parentales, from February 13 to 21, the family would go to the tombs of their dead in order to bring them gifts. Since the period ended on February 21 with a public feast called the Feralia, the following day, February 22, reverted to a private feast, the Caristia or Cara Cognatio, in which the members of the family gathered and comforted one another around a banquet. This explains the compelling need in an old family for legitimate offspring (either by bloodline or by adoption). In their turn, the duty of the descendants was to carry on the family worship and to calm the souls of their ancestors. Foundations or donations to associations could serve the same purpose. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024