MYSTERY CULTS IN THE GREEK AND ROMAN WORLD

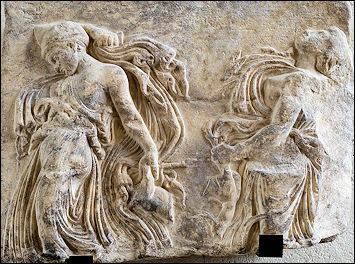

Dancing maenads There were hundreds of local gods and hundreds of cults, many devoted to specific gods. Many of the cults, were very secretive and had special initiation rituals with sacred tales, symbols, formulas and special rituals oriented towards specific gods. These are often described as mystery cults. Fertility cults and goddesses were often associated with the moon because its phases coincided the menstruation cycles of women and it was thought the moon had power over women. The word “mystery” come from the Greek word “mysterion,” which has a range of meanings, from the specific “Eleusinian ritual” to the more general “secret knowledge”. It often inferred something which one was initiated into.

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote:“Shrouded in secrecy, ancient mystery cults fascinate and capture the imagination. A pendant to the official cults of the Greeks and Romans, mystery cults served more personal, individualistic attitudes toward death and the afterlife. Most were based on sacred stories (hieroi logoi) that often involved the ritual reenactment of a death-rebirth myth of a particular divinity. In addition to the promise of a better afterlife, mystery cults fostered social bonds among the participants, called mystai. Initiation fees and other contributions were also expected. [Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

Mystery Cults generally had some kind of initiation. On initiations, Plato wrote that Socrates said: “I fancy that those men who established the mysteries were not unenlightened, but in reality had a hidden meaning when they said long ago that whoever goes uninitiated and unsanctified to the other world will lie in the mire, but he who arrives there initiated and purified will dwell with the gods. For as they say in the mysteries, 'the thyrsus-bearers are many, but the mystics few'; and these mystics are, I believe, those who have been true philosophers. And I in my life have, so far as I could, left nothing undone, and have striven in every way to make myself one of them. But whether I have striven aright and have met with success, I believe I shall know clearly, when I have arrived there, very soon, if it is God's will. [Source: Plato. “Plato in Twelve Volumes,” Vol. 1 translated by Harold North Fowler; Introduction by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1966]

The popularity and importance of the mysteries can be seen owing to the great number of those who sought initiation. They represented the religious myths, and their form corresponded to the ordinary religious worship; the mystery was due simply to the fact that in the myth the symbolic and allegorical elements prevailed, and in the worship the purifications and expiations had a specially important place. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Book: “Mystery Cults in the Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden (Thames and Hudson, 2010)

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Mystery Cults in the Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Secret Sacred: Mystery Cults in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Damien Stone (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Mystery-Religions” by S. Angus (2011) Amazon.com;

“Greek Mysteries” by Michael B. Cosmopoulos (2003) Amazon.com;

“Mysteries of Demeter : Rebirth of the Pagan Way” by Jennifer Reif (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Eleusinian and Bacchic Mysteries” by Thomas Taylor (1758-1835) Amazon.com;

“Eleusis and the Eleusinian Mysteries” by George Emmanuel Mylonas (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries” by R. Gordon Wasson , Albert Hofmann , et al. (2008) Amazon.com;

“ Bronze Age Eleusis and the Origins of the Eleusinian Mysteries” by Michael B. Cosmopoulos (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Cults: A Guide” by Jennifer Larson Amazon.com;

“The Greeks and the Irrational” by E. R. Dodds (1951) Amazon.com;

“Greek Heroine Cults” by Jennifer Larson (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Greco-Roman Cult of Isis” by Harold R. Willoughby (2017) Amazon.com;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion” by Matthew Dillon (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (1983) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

“A History of Greek Religion” by Martin P. Nilsson (1925) Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 1: A History” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 2: A Sourcebook” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street Corner” by Harriet I. Flower (2017) Amazon.com;

“Magic and Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World” by Radcliffe G. Edmonds III and Carolina López-Ruiz (2023) Amazon.com

Mysteries of Mystery Cults

Our knowledge of these secret doctrines is very small, as is natural under the circumstances, and, consequently, the most recent investigations have led to very different hypotheses. Still, discoveries enable us to feel sure that these mysteries were not, as was formerly supposed, remains of ancient revealed wisdom containing purer and better doctrines than were known to the popular religion; nor were they, as Voss supposes, merely priestly trickery.

Some ceremonies connected therewith, such as sacrifices, signs, dances, etc., bore a strongly orgiastic and ecstatic character. There were also dramatic or pantomimic representations of the mythical actions, and a great number of artistic and decorative means were used to dispose the mind of the initiated to a condition suited for solemn and mysterious doctrines. There were no really deep secrets hidden behind these mysteries, which were so numerous that almost each god had his own; and indeed, the initiation was not a difficult one, and was open to every free and blameless Greek.

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: ““Mystery cults continue to vex scholars because the surviving evidence is problematic, comprising a few written sources, mostly late in date, and often with questionable aims and biases. Modern reconstructions that view the mysteries as a cohesive religious phenomenon run the risk of oversimplification. Early twentieth-century scholarship, for instance, interpreted the ancient mysteries as a forerunner to Christian soteriological beliefs, thus challenging the latter's originality. The often interchangeable terminology found in the ancient texts, which encompasses variant ritual structures such as initiation and ecstasy (mysteria, mystes, telete, orgia), has encouraged the conception of unifying themes. Yet the wide variety and highly localized nature of these cults defy attempts at summary. One need only contrast the belief of the Neoplatonist philosopher Iamblichus that the purpose of the mysteries is purification and direct contact with the gods with the proclamation of the Christian apologist Clemens of Alexandria: "Here we see what mysteries are, in one word, murders and burials."”[Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

Mysterious Things That Mystery Cult Members Did

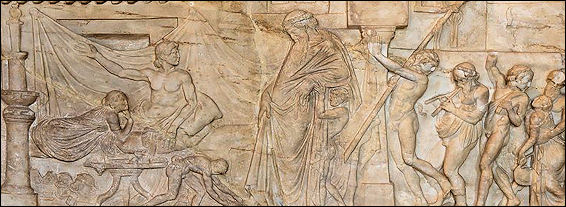

Dionysiac procession What went on in the mystery cult meetings and initiations is still largely a mystery. Members were expected to keep their “secret knowledge” secret. Altars for Hercules Roman initiation ceremonies depicted in a painting at the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii, shows devotees reading liturgy, making offerings, symbolically suckling a goat, unveiling a mystic phallus, whipping themselves (symbolic of ritual death), dancing to resurrection and preparing for holy marriage.

Cambridge classics professor Mary Beard wrote in the Times of London, “Livy includes in his history of Rome a lurid tale of the cult of Bacchus, which stresses debauchery, murder and a clever trick with sulphurous torches, which stayed alight even when plunged into the waters of the Tiber. Early Christian writers found these initiatory cults a predictably easy target. Clement of Alexandria, for example, at the end of the second or beginning of the third century AD, tried to forge an etymological link between the ritual cry of the Bacchic worshippers (“euan, euoi”) and the Judaeo-Christian figure of Eve — helped by a reputed fondness of the Bacchists for snakes. Clement's idea was that they were actually worshipping the originator of human sin. [Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, June 2010 ==]

In a review of the book “Mystery Cults in Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden, Beard wrote: “For modern scholars, it has always been a frustrating task to discover the secret of these ancient mystery cults. What was it that the initiates of Dionysus or the “Great Mother” knew that the uninitiated did not? In his refreshing new survey, “Mystery Cults in Ancient World,” Hugh Bowden suggests that we have perhaps been worrying unnecessarily about that question. In fact, we don't have to imagine the ancients were so much better keepers of secrets than we are, for no secret knowledge, as such, was transmitted at all. To be sure, there was a whole range of objects involved in these cults that outsiders could not see, and words that they were not allowed to hear. (In the cult at Eleusis, from descriptions of the public procession to the sanctuary, we can judge that the cult objects were small — at least small enough comfortably to be carried in containers by the priestesses.) But that is quite different from thinking that some particular piece of secret doctrine was revealed to the faithful at their initiation.”

How true some of the descriptions of cult activities were is a matter of debate. Beard wrote that Bowden “takes many scholars to task (myself included) for assuming that the cult of the Great Mother in Rome, based on the Palatine Hill, just next to the Roman imperial palace, was served by ecstatic eunuch priests who castrated themselves with a piece of flint. Some of us had already been a little more circumspect about this than Bowden allows: you only have to read accounts of pre-modern full castration (for the Great Mother was supposed to demand the removal of both penis and testicles) to recognize that few priests could have survived any such procedure. But he shows that, feasible or not, the practice is anyway much less clearly attested in Roman literature than we like to think. “More often than not, in fact, the details of these cults may not be quite as they seem." Bowden “cites an intriguing second-century AD inscription from just outside Rome, listing the members of a Bacchic troupe (or thiasos), under a priestess called Agripinilla. It is anyone's guess whether we see here a group of respectable Roman men and women really imitating the mad Bacchants of Euripides’ play, and taking to the mountains in religious fervour — or whether this was the ancient equivalent of modern morris dancing (that is to say the Roman equivalent group of bank managers on their days off pretending to be lusty medieval rustics). My hunch, as Bowden almost suggests, is the latter.

“This overlap between civic and initiatory religion comes out particularly vividly in a series of inscriptions commemorating leading pagan aristocrats of the late Roman Empire, which proudly list all their religious offices — initiation into mystery cults next to official state priesthoods. These were men who boasted of holding the traditional offices of augur or pontifex, as well as of being initiated into the cult of Mithras or Egyptian Isis. Bowden rightly focuses on these at the end of his book and argues against a common view that they reflect a new form of aggressive pagan religiosity, developed in response to the rise of Christianity, or that they are part of a pagan “revival” in a Christian context. Much more likely they show — albeit under the magnifying glass of late imperial Rome (where everything appears larger than life) — just how closely different forms and styles of cult, “mystery” or not, had always gone hand in hand. However secretive they might have been about what went on in their ceremonies, however uncertain or elusive the “message” of the cults might have been amid all that sound and light — initiation in a variety of different cults was something that these late antique aristocrats were happy to parade.

Analysis of Mystery Cults in Ancient Greece

Eleusinian Caryatid

Beard wrote, “Bowden would prefer to see the religious culture of the mysteries in “imagistic” terms. Drawing — perhaps a little over-enthusiastically — on recent work on the anthropology of prehistoric religions, he contrasts imagistic with doctrinal forms of religious experience. The latter are best seen in the institutionalized, regular patterns of (relatively low-key) worship, associated with modern mainstream Christianity. The former rely on the kind of striking, occasional, intense, episodic moments of religious change that are associated with ancient mystery and initiatory cults: impressive and mind-blowing maybe, but not defined by a doctrinal message (hence all that stuff about sound and light).

For Bowden, what these initiatory religions offer is a face-to-face vision of the divine. One of the big issues of Greek and Roman culture in general is exactly how far the gods are, safely, visible to mortals. The cautionary mythological tale here is that of Semele, who (as brilliantly refigured in Handel’s opera) demands to look at her lover, Jupiter, only to be destroyed by that vision of godhead. In standard ancient ritual practice, there were all kinds of ways in which the worshipper’s direct vision of the gods was avoided (through representation in statues, for example). Bowden shows convincingly that the mysteries broke through this veil, and offered a direct vision of the god — and, unlike Semele’s experience, one that did not kill the worshipper. As Lucius, the initiand in the cult of Isis in Apuleius” novel The Golden Ass, observes: “I approached the gods below and the gods above face-to-face, and worshipped them from nearby”.

But it is also the case that some of the concerns of the initiatory religions overlap strikingly with those of civic cult. Bowden rightly lays stress on all kinds of problematic issues of naming, and on the uncertainty of divine identity within mystery cults. Some mystery gods are nameless, some are addressed under a variety of alternative titles. Some inscribed texts hedge their bets: “Great Gods of Samothrace”, or “Dioscuri”, or “Kabeiroi”? Uncertainty and ambivalence, in Bowden’s view, were part of the essence of the mysteries. But so also were they part of the essence of civic cults, where those who wanted to play safe in addressing a god always hedged their bets: “whether you are god or goddess” was a standard Roman formula of prayer, just to make sure that there had been no mistake about the sex of the deity.

Likewise the question of incomprehensibility. As Bowden explains, the Greek mysteries of the island of Samothrace “included someone reciting incomprehensible words” — another index of the intellectual puzzlement at the heart of such mystery cults. But, although Bowden does not mention it, there is plenty of incomprehensibility in ancient civic, official cults too: in the first century AD, when the priests known as the “salii” danced through the streets of Rome twice a year and sang their special hymn, no one (not even the priests themselves) had the foggiest clue what the hymn meant. Perhaps in the early periods of Rome’s history, the participants had understood; or more likely it had always been mumbo-jumbo. All ancient religion celebrates its own incomprehensibility, as part of its mystique.

History of Mystery Cults

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Most mysteries started as family or clan cults and were later taken over by the city-state, the polis, as in the case of the Theban Kabeiria. Kabeiros and his son Pais, collectively known as Kabeiroi, were patrons of herdsmen worshipped in Boeotia and Lemnos. In the absence of written sources, valuable information for their enigmatic cult comes primarily from excavations at their sanctuary in Thebes. The architectural remains of the Theban Kabeirion reveal a concern with controlling access and directing foot traffic. Most probably there were preliminary sacrifices, a procession, and, at least in Roman times, initiation in two stages (epopteia and myesis) performed inside the anaktoron, the main hall of the sanctuary. [Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

Pythagoras Emerging from the Underworld by Salvator Rosa

“Numerous votive figurines of bulls, often inscribed, have been retrieved from the site together with a very distinctive type of locally manufactured pottery, the so-called kabeirion ware. Beginning around 450 B.C., these are almost exclusively drinking cups, either black-glazed or decorated with black-figure vegetation motifs, and less often, Pygmy-like grotesque figures. Understood in the context of the symposium, these vases were probably custom made according to the specifications of the cult participants. \^/

“Known among the Greeks as Kybele, or Great Mother of the Gods (Matar Kubileya, mother of mountains in Phrygia, or Kubaba in neo-Hittite), originated in Anatolia, where there was a long-standing tradition of worshipping mother figures. It was imagined that Kybele resided on inaccessible mountain tops where she ruled over wild animals. The goddess is represented wearing a long belted dress, a polos headdress, and a veil. She is seated on a throne flanked by two lions and holds a tympanon, a circular drum resembling a tambourine, and a libation bowl . Ritual purity was a prerequisite of initiation into the ecstatic cult of the Mother. Her priests, the Korybantes, and followers worshipped her with wild, loud music produced by cymbals and frenzied dancing, which, like the revels in honor of Dionysos, carried the participants despite and beyond themselves. By the third century B.C., the Mother became important at Ilium and Pergamon and hence eventually Rome, where she was worshipped as Magna Mater. \^/

“In 395 A.D., the sanctuary of Eleusis was destroyed by the Goths and was never rebuilt. The Emperor Theodosius with a series of decrees forbade pagan worship and ordered the destruction of temples and altars. By the fifth century, the mysteries were extinct.”

Personal Piety, Mystery Cult Membership and Talisman

On personal piety in Rome, Lucius Apuleius (c.123-c.170 A.D.) wrote in Apologia 55-6: “ I might discourse at greater length on the nature and importance of such accusations, on the wide range for slander that this path opens for Aemilianus, on the floods of perspiration that this one poor handkerchief, contrary to its natural duty, will cause his innocent victims! But I will follow the course I have already pursued. I will acknowledge what there is no necessity for me to acknowledge, and will answer Aemilianus' questions. You ask, Aemilianus, what I had in that handkerchief. Although I might deny that I had deposited any handkerchief of mine in Pontianus' library, or even admitting that it was true enough that I did so deposit it, I might still deny that there was anything wrapped up in it. If I should take this line, you have no evidence or argument whereby to refute me, for there is no one who has ever handled it, and only one freedman, according to your own assertion, who has ever seen it. Still, as far as I am concerned I will admit the cloth to have been full to bursting. Imagine yourself, please, to be on the brink of a great discovery, like the comrades of Ulysses who thought they had found a treasure when they stole the bag that contained all the winds. Would you like me to tell you what I had wrapped up in a handkerchief and entrusted to the care of Pontianus' household gods? You shall have your will. [Source: “Apologia and Florida Of Apuleius of Madaura, translated by H.E.. Butler Fellow of New College, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1909, gutenberg.org]

bacchanal

“I have been initiated into various of the Greek mysteries, and preserve with the utmost care certain emblems and mementoes of my initiation with which the priests presented me. There is nothing abnormal or unheard of in this. Those of you here present who have been initiated into the mysteries of father Liber alone, know what you keep hidden at home, safe from all profane touch and the object of your silent veneration. But I, as I have said, moved by my religious fervour and my desire to know the truth, have learned mysteries of many a kind, rites in great number, and diverse ceremonies. This is no invention on the spur of the moment; nearly three years since, in a public discourse on the greatness of Aesculapius delivered by me during the first days of my residence at Oea, I made the same boast and recounted the number of the mysteries I knew. That discourse was thronged, has been read far and wide, is in all men's hands, and has won the affections of the pious inhabitants of Oea not so much through any eloquence of mine as because it treats of Aesculapius. Will any one, who chances to remember it, repeat the beginning of that particular passage in my discourse? You hear, Maximus, how many voices supply the words. I will order this same passage to be read aloud, since by the courteous expression of your face you show that you will not be displeased to hear it. (The passage is read aloud.)

“Can any one, who has the least remembrance of the nature of religious rites, be surprised that one who has been initiated into so many holy mysteries should preserve at home certain talismans associated with these ceremonies, and should wrap them in a linen cloth, the purest of coverings for holy things? For wool, produced by the most stolid of creatures and stripped from the sheep's back, the followers of Orpheus and Pythagoras are for that very reason forbidden to wear as being unholy and unclean. But flax, the purest of all growths and among the best of all the fruits of the earth, is used by the holy priests of Egypt, not only for clothing and raiment, but as a veil for sacred things. And yet I know that some persons, among them that fellow Aemilianus, think it a good jest to mock at things divine. For I learn from certain men of Oea who know him, that to this day he has never prayed to any god or frequented any temple, while if he chances to pass any shrine, he regards it as a crime to raise his hand to his lips in token of reverence. He has never given firstfruits of crops or vines or flocks to any of the gods of the farmer, who feed him and clothe him; his farm holds no shrine, no holy place, nor grove. But why do I speak of groves or shrines? Those who have been on his property say they never saw there one stone where offering of oil has been made, one bough where wreaths have been hung. As a result, two nicknames have been given him: he is called Charon, as I have said, on account of his truculence of spirit and of countenance, but he is also—and this is the name he prefers—called Mezentius, because he despises the gods. I therefore find it the easier to understand that he should regard my list of initiations in the light of a jest. It is even possible that, thanks to his rejection of things divine, he may be unable to induce himself to believe that it is true that I guard so reverently so many emblems and relics of mysterious rites. I care not a straw what Mezentius may think of me; but to others I make this announcement clearly and unshrinkingly. If any of you that are here present had any part with me in these same solemn ceremonies, give a sign and you shall hear what it is I keep thus. For no thought of personal safety shall induce me to reveal to the uninitiated the secrets that I have received and sworn to conceal.”

Dionysos

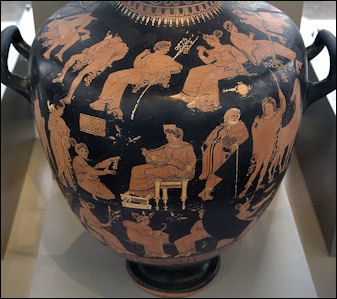

Dionysus Cult

Because his half-breed status made his position at Olympus tenuous, Dionysus did everything he could to make his mortal brethren happy. He gave them rain, male semen, the sap of plants and "the lubricant and stimulant of dance and song" — wine.

In return the Greeks held winter-time festivals in which large phalluses was erected and displayed, and competitions were held to see which Greek could chug his or her jug of wine the quickest. Processions with flute players, garland bearers and honored citizens dressed as satyrs and nymphs were staged, and at the end of the procession a bull was sacrificed. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

The text believed to be from funeral of an Dionysus cult initiate read: “I am a son of Earth and Starry Sky; but I am desiccated with thirst and am perishing, therefore give me quickly cool water flowing from the lake of recollection.” The “long, cared way which also other...Dionysus followers gloriously walk” is “the holy meadow, for which the initiate is not liable for penalty” or “shall be a god instead of a mortal.”

During Thesmophoria, an annual Athenian event to honor Demeter and Persephone, women and men who required to abstain from sex and fast for three days. Women erected bowers made of branches and sat there during their fast. On the third day they carried serpent-shaped images thought to have magical powers and entered caves to claim decayed bodied of piglets left the previous years. Pigs were sacred animals to Demeter. The piglet remains were laid on an Thesmphoria altar with offerings, launching a party with feasting, dancing and praying. This rite also featured little girls dressed up as bears.

See Separate Article: DIONYSUS CULT europe.factsanddetails.com

Eleusinian Mysteries

Eleusinian hydria Antikensam Mary Beard wrote in the Times of London, “The ancient Greeks and Romans must have been very good at keeping secrets. Or so our lack of information on the famous “Eleusinian Mysteries” (celebrated in an impressive sanctuary just a few miles outside Athens) would suggest — not to mention our lack of information on all the other, similar, initiatory religions found throughout the ancient world, from the ecstatic cult of Dionysus featured in Euripides’ Bacchae to the worship of the god Mithras by the Roman squaddies on Hadrian’s wall. There must have been literally hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of initiates, across the millennium of Classical history. And at Eleusis they included some of the most prominent (and garrulous) writers, thinkers and politicians of antiquity: Socrates and Plato, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius, and many more. These cults are often set apart, by modern writers, from the calmer, less participatory, less emotional traditions of Graeco-Roman state religion. But we have no explicit ancient account of what the secret mysteries of any cult actually were, what happened at initiation or what exactly was revealed to the initiates. So far as we can now tell, there was hardly a leaky vessel among them; or, at any rate, whatever the gossip on the ancient street, there was no one who risked committing the religious secrets to writing and so sharing them with posterity. [Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, June 2010]

It is true that on one notorious occasion, in the middle of the Peloponnesian War just before the disastrous expedition sailed to Sicily, a group of elite young Athenians were said to have parodied the Eleusinian Mysteries at private parties, and so “revealed the secret things to the uninitiated”. The jape (assuming it was no more than that) had a deathly serious end. Prosecuted for the offence, the men were found guilty and — those that had not escaped into exile first — were executed. But we hear of nothing of that kind ever again. The attitude of Pausanias in his second-century ad Guide to Greece is far more typical. Whenever he comes to describe a sanctuary of a secret cult of this type, he makes it very clear that he cannot give the game away. At Eleusis he even claims to have been warned in a dream not to divulge any of “the things within the wall of the sanctuary” — because “the uninitiated [that is, many of his readers] are not allowed to learn about what they cannot take part in”.

In the absence of any explicit eyewitness (or even second-hand) accounts, we have to rely on various kinds of indirect evidence. There are some general descriptions of initiation by ancient writers, which often dwell on strange sounds and bright lights, or the clash of light and dark. There are some notable works of literature which may engage with the theology of these cults: the so-called “Homeric Hymn to Demeter”, which tells the story of Demeter’s grief after the rape of her daughter Persephone by Hades, is often thought to reflect the myth underlying the rituals at Eleusis. There are also a number of speculative, and probably almost entirely imaginary, accounts written by ancient critics of the cults.

See Separate Article: ELEUSINIAN MYSTERY CULTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Demeter-Eleusinian Mystery Cults

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In classical antiquity, the earliest and most celebrated mysteries were the Eleusinian. At Eleusis, the worship of the agricultural deities Demeter and her daughter Persephone, also known as Kore, was based on the growth cycles of nature. Athenians believed they were the first to receive the gift of grain cultivation from Demeter. [Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

Basket of snakes on a Roman sarcophagus

“Extraordinarily, the goddess herself revealed to them the solemn rites in her honor, as we learn in the Homeric hymn to Demeter, which relates the foundation myth of the Eleusinian cult. Hades abducted Persephone while she was picking flowers with her companions in a meadow and carried her off to the Underworld. After wandering in vain looking for her daughter, Demeter arrived at Eleusis. There the wrath of the distressed mother caused a complete failure of the crops, prompting Zeus to order his brother Hades to return the girl. He cunningly tricked Persephone into eating some pomegranate seeds before leaving, thus condemning her to spend part of the year in the Underworld as his wife and the rest among the living with Demeter.

“During the Great Eleusinia, the public aspect of which culminated in the grand procession from the center of Athens to Eleusis along the Sacred Way, the actions and experiences of the initiates mirrored those of the two goddesses in the sacred drama (drama mystikon). In the early sixth century B.C., the "Queen of the Underworld" persona of Kore was introduced and a nocturnal initiation rite called katabasis was added to the festival: a simulated descent to Hades and ritual search for Persephone. Before the entrance to the Telesterion, the central hall of the sanctuary where the secret rites were performed, priestly personnel holding torches met up with the initiates, who until then were wandering in the dark. At the Eleusinian mysteries, the tension between public and private, conspicuous and secret was inherent in the double nature of the cult. Unlike city-state (polis) religion, participation was restricted to individuals who chose to be initiated, to become mystai. At the same time, it was far more inclusive, being open not only to Athenian male citizens, but to non-Athenians, women, and slaves.” \^/

See Separate Article: DEMETER MYSTERY CULTS AND MYTHS, STORIES AND HYMNS ABOUT DEMETER europe.factsanddetails.com

Cult of the Great Gods at Samothrace

Samothrace, a rocky island in the northern Aegean Sea, was home to the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, a mystery cult devoted to enigmatic deities who were thought to grant protection to seafarers. Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology Magazine: During the day, Samothrace is often veiled by clouds. Wind sweeps across the landscape, and the turbulent waters remain, as they were in antiquity, dangerous for seafarers. When the clouds clear at night, however, the peak of Mount Fengari at the island’s center, which reaches a mile into the sky, becomes visible. From the vantage point of the peak, Nestled in a deep ravine in the mountain’s shadow lie the remains of the Sanctuary of the Theoi Megaloi, or Great Gods. [Source:Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2021]

From at least the seventh century B.C., pilgrims walked under the cover of darkness from the nearby ancient city, now known as Palaeopolis, to the sanctuary to be inducted into a secret religious cult. As they passed through an immense marble gateway onto the sanctuary’s eastern hill, they might have heard the rush of water coursing through a channel beneath the entranceway. Amid the sounds of music and chanting emanating from farther within the sanctuary, the prospective initiates reached a sunken circular court. Here, ritual dancing and other performances might have taken place, surrounded by bronze statues that were likely dedicated by previous initiates. The noise and darkness, as well as the use of blindfolds, probably induced an altered state of mind that prepared participants for the forthcoming rituals and sacred revelations. By the flickering light of oil lamps and torches, they began the steep descent down the Sacred Way, to the sanctuary’s heart, to be initiated into the mysteries of the Great Gods.

Because initiates were bound to keep the details of the rites secret, ancient literary sources provide scant details about the cult. Those writers who do discuss the mysteries often give diverging accounts and differing identifications of the gods. Coins dating to the second-century B.C. unearthed at the sanctuary depict a great mother goddess. Some ancient writers associate this goddess with a group of gods called the Kabeiroi. “What we know most clearly about the initiation are its promises and benefits,” says archaeologist Bonna Wescoat of Emory University. “Ancient sources strongly state that the Great Gods are powerful and protective gods. Most say they offer protection at sea, while some say they offer protection in times of need. The benefits they confer could have meant different things to different people, depending on what an initiate most sought from the experience.” Some writers even claim that initiates experienced a moral transformation. According to the first-century B.C. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, initiates into the Samothracian mysteries became “more pious and more just and better in all ways than they had been before.”

See Separate Article: CULT OF THE GREAT GODS AT SAMOTHRACE europe.factsanddetails.com

Roman Mystery Cults

Mystery cults dedicated to Bachus were popular in the Roman Empire. Cults for Isis and Osiris and Mithras were popular with traders and soldiers. Initiates to cults honoring Cybele in Asia Minor were baptized in bull blood, which some thought ensured eternal life. Once accepted into the cult devotees were expected to castrate themselves as offering of their fertility in exchange for the fertility of the world. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Scholars have long argued that the idea of mystery cults was introduced to Rome from the East. Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “The weakening of the old stock and the constantly increasing number of Orientals in the West, along with the campaigns of the armies in the East naturally encouraged the introduction of eastern cults and the spread of their influence. The cult of the Magna Mater found a reviving interest among the people from her part of the world. The mystery religions gained strength, with their rites of purification and assurance of happiness after death. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

“Among them the worship of Isis had come from Alexandria with the Egyptians and spread among the lower classes. Mithraism came in from the eastern campaigns with the captives, and later with the troops that had served or had been enlisted in the East. It established itself in Rome and in other cities and followed the army from camp to camp. There were many Jews in Rome, and their religion made some progress. Christianity appeared at Rome first among the lower classes, particularly the Orientals, and finally made its way upward.” |+|

Magna Mater (Cybele) Cults

Magna Mater (Cybele)

Magna Mater ("Great Mother") was the Roman version of Cybele, an Anatolian mother goddess that may date back to 10,0000-year-old Çatalhöyük, the world’s oldest town, where statues of plump women, sometimes sitting, have been found in excavations. She is Phrygia's only known goddess, and was probably its state deity. Her Phrygian cult was adopted and adapted by Greek colonists of Asia Minor and spread to mainland Greece and its more distant western colonies around the 6th century B.C.. Some scholars say the cult of Cybele was brought to Rome in 205 or 204 B.C.. The Roman state adopted and developed a particular form of her cult after the Sibylline oracle recommended her conscription as a key religious ally in Rome's second war against Carthage. Roman mythographers reinvented her as a Trojan goddess, and thus an ancestral goddess of the Roman people by way of the Trojan prince Aeneas. With Rome's eventual hegemony over the Mediterranean world, Romanized forms of Cybele's cults spread throughout the Roman Empire. The meaning and morality of her cults and priesthoods were topics of debate and dispute in Greek and Roman literature, and remain so in modern scholarship. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In 204 B.C., during the Second Punic War, the Romans consulted the Sibylline Oracles, which declared that the foreign invader would be driven from Italy only if the Idaean Mother (Cybele) from Anatolia were brought to Rome. The Roman political elite, in a carefully orchestrated effort to unify the citizenry, arranged for Cybele to come inside the pomerium (a religious boundary-wall surrounding a city), built her a temple on the Palatine Hill, and initiated games in honor of the Great Mother, an official political and social recognition that restored the pax deorum. [Source: Claudia Moser, Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“After Cybele and the foreign ways of her exotic priesthood were introduced to Rome, she became a popular goddess in Roman towns and villages in Italy. But the enthusiasm that accompanied the establishment of her cult was soon followed by suspicion and legal prohibitions. The eunuch priests (galli) that attended Cybele's cult were confined in the sanctuary; Roman men were forbidden to castrate themselves in imitation of the galli, and only once a year were these eunuchs, dressed in exotic, colorful garb, allowed to dance through the streets of Rome in jubilant celebration. Nevertheless, the popularity of the goddess persisted, especially in the Imperial period, when the ruling family, eager to emphasize its Trojan ancestry, associated itself with and publicly worshipped Cybele, a goddess whose epithet, Mater Idaea, designated her as Trojan and whose cult was deeply connected with Troy and its origins.” \^/

See Separate Article: MAGNA MATER (CYBELE) CULTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii

James W. Jackson wrote in the Villa of Mysteries website: “This villa, built around a central peristyle court and surrounded by terraces, is much like other large villas of Pompeii. However, it contains one very unusual feature; a room decorated with beautiful and strange scenes. This room, known to us as "The Initiation Chamber," measures 15 by 25 feet and is located in the front right portion of the villa. [Source: James W. Jackson, Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii website]

“The term "mysteries" refers to secret initiation rites of the Classical world. The Greek word for "rite" means "to grow up". Initiation rites, then, were originally ceremonies to help individuals achieve adulthood. The rites are not celebrations for having passed certain milestones, such as our high school graduation, but promote psychological advancement through the stages of life. Often a drama was enacted in which the initiates performed a role. The drama may include a simulated death and rebirth; i.e., the dying of the old self and the birth of the new self. Occasionally the initiate was guided through the ritual by a priest or priestess and at the end of the ceremony the initiate was welcomed into the group.

“The chamber is entered through an opening located between the first and last scenes of the fresco The fresco images seem to part of a ritual ceremony aimed at preparing privileged, protected girls for the psychological transition to life as married women. The frescoes in the Villa of Mysteries provide us the opportunity to glimpse something important about the rites of passage for the women of Pompeii. But as there are few written records about mystery religions and initiation rites, any iconographic interpretation is bound to be flawed. In the end we are left with the wonderful frescoes and the mystery. Nevertheless, an interpretation is offered, see if you agree or disagree.

“At the center of the frescoes are the figures of Dionysus, the one certain identification agreed upon by scholars, and his mother Semele (other interpretations have the figure as Ariadne). As he had been for Greek women, Dionysus was the most popular god for Roman women. He was the source of both their sensual and their spiritual hopes.

Scenes in Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii

James W. Jackson wrote in the Villa of Mysteries website: “Scene 1: The action of the rite begins with the initiate or bride crossing the threshold as the preparations for the rites to begin. Her wrist is cocked against her hip. Is she removing her scarf? Is she listening to the boy read from the scroll? Is she pregnant? The nudity of the boy may signify that he is divine. Is he reading rules of the rite? He wears actor's boots, perhaps indicating the dramatic aspect of the rites. The officiating priestess (behind the boy) holds another scroll in her left hand and a stylus in her right hand. Is she prepared to add the initiate's name to a list of successful initiates?” Later, “The initiate, now more lightly clad, carries an offering tray of sacramental cake. She wears a myrtle wreath. In her right hand she holds a laurel sprig. [Source: James W. Jackson, Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii website]

“Scene 2: A priestess, wearing a head covering and a wreath of myrtle removes a covering from a ceremonial basket held by a female attendant. Speculations about the contents of the basket include: more laurel, a snake, or flower petals. A second female attendant wearing a wreath, pours purifying water into a basin in which the priestess is about to dip a sprig of laurel. Mythological characters and music are introduced into the narrative. An aging Silenus plays a ten-string lyre resting on a column.

“Scene 3: A young male satyr plays pan pipes, while a nymph suckles a goat. The initiate is being made aware of her close connection with nature. This move from human to nature represents a shift away from the conscious human world to our preconscious animal state. In many rituals, this regression, assisted by music, is requisite to achieving a psychological state necessary for rebirth and regeneration. The startled initiate has a glimpse of what awaits her in the inner sanctuary where the katabasis will take place. This is her last chance to save herself by running away. Perhaps some initiates did just that. The next scene provides hints about what both frightens and awaits the initiate.

Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii

“Scene 4: “The Silenus looks disapprovingly at the startled initiate as he holds up an empty silver bowl. A young satyr gazes into the bowl, as if mesmerized. Another young satyr holds a theatrical mask (resembling the Silenus) aloft and looks off to his left. Some speculate that the mask rather than the satyr's face is reflected in the silver bowl. So, looking into the vessel is an act of divination: the young satyr sees himself in the future, a dead satyr. The young satyr and the young initiate are coming to terms with their own deaths. In this case the death of childhood and innocence. The bowl may have held Kykeon, the intoxicating drink of participants in Orphic-Dionysian mysteries, intended for the frightened initiate.

“Scene 5: This scene is at the center of both the room and the ritual. Dionysus sprawls in the arms of his mother Semele. Dionysus wears a wreath of ivy, his thyrsus tied with a yellow ribbon lies across his body, and one sandal is off his foot. Even though the fresco is badly damaged, we can see that Semele sits on a throne with Dionysus leaning on her. Semele, the queen, the great mother is supreme.

“Scene 6: The initiate, carrying a staff and wearing a cap, returns from the night journey. What has happened is a mystery to us. But in similar rituals the confused, and sometimes drugged initiate emerges like an infant at birth, from a dark place to a lighted place. She reaches for a covered object sitting in a winnowing basket, the liknon. The covered object is taken by many to be a phallus, or a herm. To the right is a winged divinity, perhaps Aidos. Her raised hand is rejecting or warding off something. She is looking to the left and is prepared to strike with a whip. Standing behind the initiate are two figures of women, unfortunately badly damaged. One woman (far left) holds a plate with what appear to be pine needles above the initiate's head. The apprehensive second figure is drawing back.

“Scene 7: The two themes of this scene are torture and transfiguration, the evocative climax of the rite. Notice the complete abandonment to agony on the face of the initiate and the lash across her back. She is consoled by a woman identified as a nurse. To the right a nude women clashes celebratory cymbals and another woman is about to give to the initiate a thyrsus, symbolizing the successful completion of the rite.

“Scene 8: This scene represents an event after the completion of the ritual drama. The transformed initiate or bride prepares, with the help of an attendant, for marriage. A young Eros figure holds a mirror which reflects the image of the bride. Both the bride and her reflected image stare out inquiringly at us, the observers.

“Scene 9: The figure above has been identified as: the mother of the bride, the mistress of the villa, or the bride herself. Notice that she does wear a ring on her finger. If she is the same female who began the dramatic ritual as a headstrong girl, she has certainly matured psychologically. Scene 10: Eros, a son of Chronos or Saturn, god of Love, is the final figure in the narrative.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~\; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024