ANCIENT ROMAN RITUALS

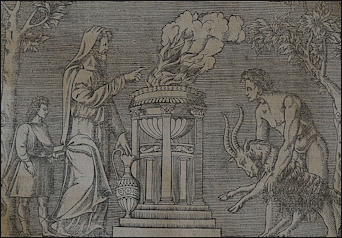

ritual performed by vestal virgins

Romans showed their respect and reverence of the gods in their prayers, offerings, and festivals. The prayers were addressed to the gods for the purpose of obtaining favors, and were often accompanied by vows. The religious offerings consisted either of the fruits of the earth, such as flowers, wine, milk, and honey; or the sacrifices of domestic animals, such as oxen, sheep, and swine. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The aim of public worship was to assure or to restore the "benevolence and grace of the gods," which the Romans considered indispensable for the state's well-being. Annually returning rituals dominated public cultic activity. The festivals which were celebrated in honor of the gods were very numerous and were scattered through the different months of the year. The old Roman calendar contained a long list of these festival days. The new year began with March and was consecrated to Mars and celebrated with war festivals. Other religious festivals were devoted to the sowing of the seed, the gathering of the harvest, and similar events which belonged to the life of an agricultural people such as the early Romans were. \~\

Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University wrote for the BBC: “The actual substance of the Roman state religion lay in ritual rather than individual belief, and was collective rather than personal. The rituals consisted of festivals, offerings (often of food or wine) and animal sacrifices. These rituals had to be carried out regularly and correctly in order to retain the favour of the gods towards the state, household or individual. The absence of strong elements of personal belief, salvation and morality in the Roman state religion may be one of the reasons why certain kinds of philosophy (like that of Stoicism) and non-state cults (like Isis-worship or Mithraism, for example - see image 8) were popular alongside the state religion. [Source: Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street Corner” by Harriet I. Flower (2017) Amazon.com;

“Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Alexandra Sofroniew (2015) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Animal Sacrifice: Ancient Victims, Modern Observers”

by Christopher A. Faraone and F. S. Naiden (2012) Amazon.com;

“Senses, Cognition, and Ritual Experience in the Roman World” by Blanka Misic, Abigail Graham (2024) Amazon.com;

“Public Worship of the Ancient Greeks and Romans” by E. M. Berens, Gregory Zorzos (2009) Amazon.com;

“Magic and Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World” by Radcliffe G. Edmonds III and Carolina López-Ruiz (2023) Amazon.com

“The Divine Liver: The Art And Science Of Haruspicy As Practiced By The Etruscans And Romans” by Rev. Robert Lee Ellison (2013) Amazon.com;

“Magic in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Lindsay C. Watson Amazon.com;

“Ancient Magic: A Practitioner's Guide to the Supernatural in Greece and Rome” by Philip Matyszak (2019) Amazon.com;

"Magic, Witchcraft and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Sourcebook"

by Daniel Ogden (2009) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Necromancy” by Daniel Ogden (2004) Amazon.com;

“Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds: a Collection of Ancient Texts” by Georg Luck (1985) Amazon.com;

“Superstitious Beliefs And Practices Of The Greeks And Romans” by William Reginald Halliday (1886-1966) Amazon.com;

“Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World” by John G. Gager (1999) Amazon.com;

“Votive Body Parts in Greek and Roman Religion” by Jessica Hughes (2017) Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 1: A History” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

“Religions of Rome: Volume 2: A Sourcebook” by Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price ( Amazon.com;

"Archaic Roman Religion, Volume 1 Paperback by Georges Dumézil, Philip Krapp (1996) Amazon.com;

“Archaic Roman Religion, Volume 2" by Georges Dumézil (1996) Amazon.com;

"Roman Myths: Gods, Heroes, Villains and Legends of Ancient Rome” by Martin J Dougherty (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Religion of the Etruscans” by Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Erika Simon (2006) Amazon.com;

Sacrifices in Ancient Rome

Romans from the earliest times of their existence practiced a purifying ritual called Lupercalia. Priests sacrificed goats and a dog at the Lupercal, the cave where legend says Romulus and Remus were suckled, and their blood was smeared on two youths. Young women were whipped across their shoulders in the belief it bestowed fertility. The rite was performed in mid February at an altar near Lapis Niger, a sacred site paved with black stones near the Roman Forum until A.D. 494 when it was banned by the pope.

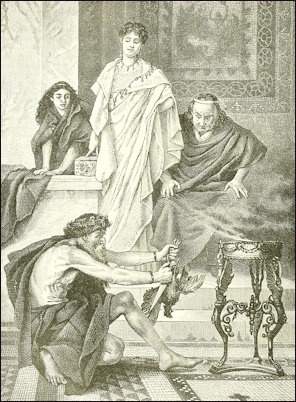

preparation for a Roman sacrifice

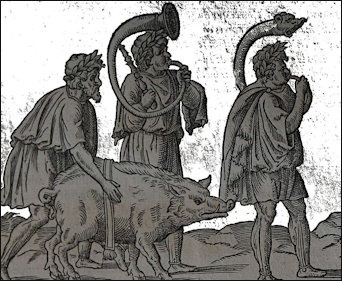

Romans held sacrifices in which a bull, a sheep and a pig were offered. There was even a word to describe it ( suovetaurilia ) which was made by combining the Roman words for the three animals. Oxen were also sacrificed. Clement of Alexandria wrote in “Stromata” (c. A.D. 200): “Sacrifices were devised by men, I do think, as a pretext for eating meals of meat.”

Both the Greeks and Romans salted their sacrifice victims before their throats were cut. Roman senators vied among themselves to see who could get the most blood on their togas during the sacrifice of steer, thinking it would prevent death. A 1,500-year-old earthenware vase that was once thought show human dismemberment actually depicted an ancient bronze statue assembly line.

Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University wrote for the BBC: ““A sculpted relief of c. AD 176-80, depicts the emperor Marcus Aurelius offering a sacrifice. He is veiled as a priest, and stands by a small altar, along with the bull that is to be sacrificed, a flute-player and (to the right) the victimarius, who actually killed the animal, with his axe. Between the emperor and the bull is a priest, a flamen, who can be identified by his distinctive headgear, which has a spike on it. |::|[Source: Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|] “Typically these rituals were performed out of doors - Roman temples were not places for group worship like modern churches, mosques or synagogues are, but were store-houses for a statue of the god, and for equipment connected with the cult. Sacrifices generally took place on an altar in front of the temple. One relief shows a temple in the background, probably the Capitoline temple of Jupiter, in Rome, with its three doors to the rooms dedicated to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva.” |::|

Military Sacrifice in Ancient Rome

Livy (59 B.C. - A.D. 17) wrote in “History of Rome” VIII, 9, 1-11: “The Roman consuls before leading their troops into battle offered sacrifices. it is said that the soothsayer pointed out to Decius that the head of the liver was wounded on the friendly side; but that the victim was in all other respects acceptable to the gods, and that the sacrifice of Manlius had been greatly successful. “it is well enough,” said Decius, “if my colleague has received favourable tokens.” in the formation already described they advanced into the field. Manlius commanded the right wing, Decius the left. in the beginning the strength of the combatants and their ardour were equal on both sides; but after a time the Roman hastati on the left, unable to withstand the pressure of the Latins, fell back upon the principes. in the confusion of this movement Decius the consul called out to Marcus Valerius in a loud voice: “we have need of Heaven's help, Marcus Valerius. come therefore, state pontiff of the Roman People, dictate the words, that I may devote myself to save the legions.” [Source: Titus Livius (Livy), “The History of Rome,” Book 8. Benjamin Oliver Foster, Ph.D., Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1926, perseus.tufts.edu]

The pontiff bade him don the purple —bordered toga, and with veiled head and one hand thrust out from the toga and touching his chin, stand upon a spear that was laid under his feet, and say as follows:“janus, Jupiter, Father Mars, Quirinus, Bellona, Lares, divine Novensiles, divine Indigites, ye gods in whose power are both we and our enemies, and you, divine Manes, —I invoke and worship you, I beseech and crave your favour, that you prosper the might and the victory of the Roman People of the Quirites, and visit the foes of the Roman People of the Quirites with fear, shuddering, and death. As I have pronounced the words, even so in behalf of the republic of the Roman People of the Quirites, and of the army, the legions, the auxiliaries of the Roman People of the Quirites, do I devote the legions and auxiliaries of the enemy, together with myself, to the divine Manes and to Earth.”

“Having uttered this prayer he bade the lictors go to Titus Manlius and lose no time in announcing to his colleague that he had devoted himself for the good of the army. he then girded himself with the Gabinian cincture, and vaulting, armed, upon his horse, plunged into the thick of the enemy, a conspicuous object from either army and of an aspect more august than a man's, as though sent from heaven to expiate all anger of the gods, and to tum aside destruction from his people and bring it on their adversaries. Thus every terror and dread attended him, and throwing the Latin front into disarray, spread afterwards throughout their entire host. This was most clearly seen in that, wherever he rode, men cowered as though blasted by some baleful star; but when he fell beneath a rain of missiles, from that instant there was no more doubt of the consternation of the Latin cohorts, which everywhere abandoned the field in flight. At the same time the Romans —their spirits relieved of religious fears —pressed on as though the signal had just then for the first time been given, and delivered a fresh attack; for the rorarii were running out between the antepilani and were joining their strength to that of the hastati and the principles, and the triarii, kneeling on the right knee, were waiting till the consul signed to them to rise.”

Human Sacrifice by the Romans

Human sacrifice was broadly practiced in all areas of the world but we tend to think of the ancient Romans as one groups that deplored it and outlawed it in their religious and political codes. To an extent, there’s some truth to this but there do appear to be some examples of it occurring. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, 2017]

At least twice during times of crisis foreign prisoners of war were buried alive. After Rome lost early battles to Hannibal and Carthage in the Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.) authorities resorted to extraordinary measures, which included consulting the Sibylline Books, dispatching a a high-level delegation to consult the Delphic oracle in Greece, and burying four people alive as a sacrifice to their gods. Twice people were buried alive at the Forum of Rome and an oversized baby was abandonedin the Adriatic Sea. These are seen as among of the last instances of human sacrifices by the Romans, apart from public executions of defeated enemies dedicated to Mars.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In warfare Roman generals were known to sacrifice themselves in battle in order to secure a victory. Livy describes how the Roman commander would dress in his official toga, cover his head, stand on a spear, and hold his hand against his chin as the priest pronounced a formula of devotio in which the general dedicated himself and the enemy troops to the gods of the underworld and the goddess of the earth for the benefit of Rome and her military forces. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, April 10, 2016]

Ozan Simitçiler posted on Quora.com in 2019: Officially the Romans were against human sacrifice but during Triumph ceremonies, prisoners of war were brought to the front of the temple of Jupiter and killed there. Killings in the arena were also sort of human sacrifice. Gladiator games were originally fights to the death in honor of deceased.

Family Worship in Ancient Rome

According to Encyclopedia.com: Family worship was centered in the house, fields, and boundaries of the farmstead. A host of numina or spirits presided over the various parts of the house and the activities of house and farm. The Penates guarded the pantry; and Janus, the door. Vesta, the spirit of fire, was present in the hearth. The pater familias had an indwelling Genius; and the mater familias, an indwelling Juno. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

seated Jupiter found in a Pompeii house

The Lares protected the fields. All these spirits were the object of cult, and the pater familias was the priest of the household — which included slaves as well as members of the family proper. A special festival, the Terminalia, was held in honor of the boundary stones, and in May the Ambarvalia was celebrated to insure the fertility of the fields. It included a solemn procession, prayers, and the sacrifice of a pig, sheep, and ox (suovetaurilia ). Other feasts, likewise connected with agriculture, were celebrated throughout the year, and magic practices of various kinds were employed to ward off evil spirits or diseases. The spirits of the dead, the Di Manes, were honored at the feast of the Lemuria, which was held in May. At first, the spirits of the dead were feared, and the rites were intended to propitiate them or drive them away. At the later feast of the Parentalia, however, relatives decorated the graves of their dead without fear and out of a feeling of duty and affection. Family religion in country areas remained at once relatively primitive and vital to the end of antiquity.

The pater familias was the household priest and in charge of the family worship; he was assisted by his wife and children. The Lar Familiaris was the protecting spirit of the household in town and country. In the country, too, the Lares were the guardian spirits of the fields and were worshiped at the crossroads (compita) by the owners and tenants of the lands that met there. In town, too, the Lares Compitales were worshiped at street-corner shrines in the various vici or precincts. For the single Lar of the Republican period we later find two. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Household Shrines in Ancient Rome

Perhaps the first divinities we think of when we turn to the native Roman religion are the Lares, the guardians of house and field. The Lar was represented as a youth holding a horn of plenty and a patera, a shallow bowl used in sacrificing. Two of these figures stood side by side near the hearth in the principal room of the early Roman house, but at a later period they were placed in a little shrine usually adjoining the atrium. A fine statuette of the Imperial period represents a priest with his toga drawn up over his head in preparation for sacrificing, in accordance with the custom which Virgil mentions in the Aeneid: “Veil thine hair with a purple garment for covering, that no hostile face at thy divine worship may meet thee amid the holy fires and make void the omens”. A life-size statue of a camillus, a boy assistant at religious rites, is in this room. The office of camillus was an honorable one bestowed upon the young sons of distinguished families. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

There were also objects related to special cults. A goddess revered by both Greeks and Romans was Tyche or Fortuna. A small bronze statuette represents the Fortune of Antioch seated on a rock, crowned with turrets, and holding in her hand a sheaf of grain. Fortuna had many temples in Rome, where she was worshipped under different titles. The popular belief in her power is attested by Caesar, who tells of the confidence felt by his men in him and in his success because they believed him to be a favorite of Fortune. The worship of the Egyptian goddess Isis gradually spread from Egypt into Asia Minor and thence into Greece and Rome. The bronze sistrum or rattle was used in her rites, and she is often represented holding it in her hand.

An especially interesting memorial of an Eastern cult established in Rome is the statuette of Cybele, the Mother of the Gods, on her processional car drawn by lion. The worship of Cybele, a very ancient one, was introduced into Rome during the Second Punic War at a time of great danger and anxiety. Our statuette represents not the goddess herself but her cult statue, and probably commemorates one of the annual festivals at which the image on its car was taken to the river Almo to receive a ritual bath. The god-companion of Cybele, Attis, was not worshipped at Rome before the time of Claudius, though his cult was diffused over many parts of the East. A little terracotta from Cyprus shows him in Phrygian dress on a horse. A glass relief gives a realistic picture of a Roman sacrifice; an ox is being led through the portico of a temple by four men carrying knives and an axe. A priestess walks before them with veiled head, holding a box containing incense, meal, or other articles used at sacrifices.

altars for Hercules

Pompeian household shrines often have representations of boys dressed in belted tunics, stepping lightly as if in dance, a bowl in the right hand, a jug upraised in the left. In place of the old Penates, the protecting spirits of the store-closet, these shrines show images of such of the great gods as each family chose to honor in its private devotions. The Genius of the pater familias may be represented in such shrines as a man with the toga drawn over his head as for worship. Often, however, at Pompeii the Genius is represented by a serpent. In such shrines we find two, one bearded, for the Genius of the father, the other for the Iuno of the wife. Vesta was worshiped at the hearth as the spirit of the fire that was necessary for man’s existence. This shrine, originally in the atrium when that was the room where the household lived and worked, followed the hearth to the separate kitchen, though examples of shrines are found in the garden or peristyle and occasion ally in the atrium or other rooms. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The devout prayed and sacrificed every morning, but the usual time for the family devotions was the pause at the cena before the secunda mensa, when offerings to the household gods were made.The Kalends, Nones, and Ides were sacred to the Lares. On these days garlands were hung over the hearth, the Lares were crowned with garlands, and simple offerings were made. Incense and wine were usual offerings; a pig was sacrificed when possible. Horace has a pretty picture of the “rustic Phidyle” who crowns her little Lares with rosemary and myrtle, and offers incense, new grain, and a “greedy pig.” The family were also bound to keep up the rites in honor of the dead. All family occasions from birth to death were accompanied by the proper rites. Strong religious feeling clung to the family rites and country festivals even when the state religion had stiffened into formalism and many Romans were reaching after strange gods. The gens or clan of which the family formed a part had its own rites. The maintenance of these sacra was considered necessary not merely for the clan itself, but for the welfare of the State, which might suffer from the god’s displeasure if the rites should be neglected.” |+|

Sacra Publica and Religious Associations in Ancient Rome

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Religion as organized by the nobility, the political elite, and paid for by state funds — hence religio publica— offered a space for religious activities for the aristocracy and the framework for various collective or individual activities on the part of ordinary citizens or simply inhabitants of Rome. The sacra publica, publicly financed ritual, were not restricted to activities of the city as a whole. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Territorial subdivisions, such as the curiae or the neighborhoods of the compitalia (crossroad sanctuaries), offered space for ritual interaction and communication. The curio maximus was the second priesthood to be included into the procedure of popular election, more than one hundred years before the augurs and the other pontiffs. In imperial times, the vicomagistri who presided over compitalician cult were given the right to wear the toga praetexta, togas with a purple strip distinguishing Roman magistrates, during their services. We do not know much about gentilician cult, but much is known about family and household cult from literary and archaeological sources, which serve as a helpful corrective against poetic or antiquarian idealization. Rented Roman flats lacked built-in altars, and the ancestor cult of deceased relatives simply dumped into the extra-urban pits might have been limited.

Sacrifices, banquets, family festivals and the use organized social space was often arranged by religious associations. The Romans believed that their associations dated back to the early regal period. Common economic interest and sociability usually went together, formally united by the cult of a suitable deity. Bakers, for example, venerated Vesta, the goddess of the hearth. In addition, slaves of large households were known to have organized themselves into associations during imperial times. Given the weak economic position of many individuals and families, associations might provide funeral services as well. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The multifunctional form of the association (collegium) often opened them to criticism and suspicion. For example, associations of venerators of the goddess Isis, originally stemming from Egypt but present at Rome from the second century B.C. onward, were regarded as political troublemakers and organizers of popular unrest in the last decennium of the Republic. Even the territorially organized groups of the compitalia were subject to suspicion, and they eventually dissolved. The most famous and best documented conflict between a religious organization and Roman officials is the persecution of the Italian Bacchanalia in 186 B.C.

Prayer of Scipio Africanus

tool used in sacrifices

Livy (59 B.C. - A.D. 17) wrote in “History of Rome” XXIX, 27, 1-4: “When the day dawned Scipio on his flagship, after silence had been secured by a herald, prayed: “Ye gods and goddesses who inhabit seas and lands, I pray and beseech you that whatever under my authority has been done, is being done, and shall henceforth be done, may prosper for me, for the Roman people and the commons, for allies and Latins who by land, by sea, and by rivers follow the lead, authority and auspices of the Roman people and of myself; and that ye lend your kind aid to all those acts and make them bear good fruit; that when the foe has been vanquished, ye bring the victors home with me safe and sound, adorned with spoils, laden with booty, and in triumph; that ye grant power to punish opponents and enemies; and that ye bestow upon the Roman people and upon me the power to visit upon the state of the Carthaginians the fate that the people of Carthage have endeavoured to visit upon our state.”

“Immediately after this prayer a victim was slain and Scipio threw the organs raw into the sea, as is customary, and by a trumpet gave the signal to sail. A favouring wind sufficiently strong quickly carried them out of sight of land. And after mid-day they encountered a fog, so that with difficulty could they avoid collisions between the ships. In the open sea the wind was gentler. Through the following night the same fog held; and when the sun was up, it was dispersed and the wind increased in force. Already they were in sight of land.

Not very long afterwards the pilot told Scipio that Africa was not more than five miles away; that they sighted the Promontory of Mercury; if he should order him to steer for that, the entire fleet would soon be in port. Scipio, now that the land was visible, after a prayer to the gods that his sight of Africa might be a blessing to the state and to himself, gave orders to make sail and to seek another landing-place for the ships farther down. They were running before the same wind; but at about the same time as on the preceding day a fog appeared cutting off the sight of land, and under the weight of fog the wind dropped. Then night added to all their uncertainties; so they cast anchor, that the ships might not collide or drift onto the shore. When day dawned the same wind sprang up and by dispelling the fog revealed the whole African coast. Scipio inquired what the nearest promontory was, and upon being told it was called Cape of the Fair God, he said “A welcome omen! steer your ships this way!” There the fleet came into port and all the troops were disembarked.

“That the passage was successful and free from alarm and disorder I have accepted on the authority of many Greek and Latin writers. Coelius alone describes all the terrors of weather and waves —everything short of saying that the ships were overwhelmed by the seas. He relates that finally the fleet was swept by the storm away from Africa to the island of Aegimurus and that from there the proper course was regained with difficulty; and that as the ships were all but sinking the soldiers, without waiting for an order from the general, made their way to the shore in small boats, as though they had been shipwrecked, with no arms and in the greatest disorder.”

Criticism of Prayer

“Persius Flaccus was a Stoic, a satirist, and a wealthy member of the knightly class. In his poems, which exist as one book, he supports robust taste over artifice, and attacks popular ideas about prayer - especially those who request worldly goods rather than virtue. In Satire II (A.D. 60) he wrote: “Mark this day, Macrinus, with a white stone, which, with auspicious omen, augments your fleeting years. Pour out the wine to your Genius! You at least do not with mercenary prayer ask for what you could not intrust to the gods unless taken aside. But a great proportion of our nobles will make libations with a silent censer. It is not easy for every one to remove from the temples his murmur and low whispers, and live with undisguised prayers. "A sound mind, a good name, integrity"---for these he prays aloud, and so that his neighbor may hear. But in his inmost breast, and beneath his breath, he murmurs thus, "Oh that my uncle would evaporate! what a splendid funeral! and oh that by Hercules' good favor a jar of silver would ring beneath my rake! or, would that I could wipe out my ward, whose heels I tread on as next heir! For he is scrofulous, and swollen with acrid bile. This is the third wife that Nerius is now taking home!"---That you may pray for these things with due holiness, you plunge your head twice or thrice of a morning in Tiber's eddies, and purge away the defilements of night in the running stream. [Source: The Satires of Juvenal, Persius, Sulpicia, and Lucilius, translated by Lewis Evans (London: Bell & Daldy, 1869), pp. 217-224]

“Think Jupiter has forgiven you, because, when he thunders, the oak is riven with his sacred bolt than you and all your house? Or because you did not, at the bidding of the entrails of the sheep, and Ergenna, lie in the sacred grove a dread bidental to be shunned of all, that therefore he gives you his insensate beard to pluck? Or what is the bribe by which you would win over the ears of the gods? With lungs, and greasy chitterlings?

vestal virgin ritual

“You ask vigor for your sinews, and a frame that will insure old age. Well, so be it. But rich dishes and fat sausages prevent the gods from assenting to these prayers, and baffle Jove himself. You are eager to amass a fortune, by sacrificing a bull and court Mercury's favor by his entrails. "Grant that my household gods may make me lucky! Grant me cattle, and increase to my flocks! How can that be, poor wretch, while so many cauls of thy heifers melt in the flames? Yet still he strives to gain his point by means of entrails and rich cakes. "Now my land, and now my sheepfold teems. Now, surely now, it will be granted! "Until, baffled and hopeless, his sestertius at the very bottom of his money-chest sighs in vain.

“Were I to offer you goblets of silver and presents embossed with rich gold, you would perspire with delight, and your heart, palpitating with joy in your left breast, would force even the tear-drops from your eyes. And hence it is the idea enters your mind of covering the sacred faces of the gods with triumphal gold. Oh! souls bowed down to earth! and void of aught celestial! Of what avail is it to introduce into the temples of the gods these our modes of feeling, and estimate what is acceptable to them by referring to our own accursed flesh. This has dyed the fleece of Calabria with the vitiated purple. To scrape the pearl from its shell, and from the crude ore to smelt out the veins of the glowing mass; this carnal nature bids. She sins in truth. She sins. Still from her vice gains some emolument.”

Early Roman Rituals

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: The standard Roman sacrificial ritual consisted essentially of a canonical prayer followed by the slaughtering of an animal and the offering of consecrated entrails (the exta) to the divinity (the distinction between exta — comprising the lungs, heart, liver, gall bladder, and peritoneum — and the viscera, flesh given over for profane consumption, is fundamental in Roman ritual). The sacrificial ceremony was celebrated by qualified magistrates or priests on private initiative around an altar placed in front of the temple. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

In new rituals introduced in the middle of the Republican period, statues of the deities reposing on cushions (pulvinaria) were displayed within the temples on ceremonial beds (lectisternia). Men, women, and children could approach them and offer them food and prayers in fervent supplication (see Livy, 24.10.13; 32.1.14).

The proliferation of games was an most important religious innovation of the middle Republic period. The combination of processional rituals parading gods and actors through the city of Rome and the competitions in circuses or the presentation of dramas on temporary stages brought religion into the central public space and enabled the participation of larger shares of the populace as spectators. Thus, the rituals gave information about foreign affairs and culture, they offered space for communication between the various social groups seated in an orderly arrangement in the theater or circus, and they produced a feeling of common identity — a victorious Roman identity.

RELIGION IN PRE-ROMAN AND REPUBLIC ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

libation

Priests in Ancient Rome

Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University wrote for the BBC: “Religious activities of the Roman state religion were overseen and presided over by priests. They were drawn from members of the ruling class of Rome, and were organised in 'colleges' and sub-groups with particular functions. For example, there were pontifices (pontiffs), augurs (associated with interpretation of auspices — signs given by the gods through the flight of birds, thunder, lightning, and other natural phenomena), haruspices (originally of Etruscan origin, consulted about prodigies), flamines or individual gods, and fetiales, associated with the declaration of war. The chief priest was known as the pontifex maximus, a title that was subsequently used by Roman Catholic popes. In the Republican period of Roman history, the priests typically were also politicians, and religious rituals could be — and were — exploited for political advantage. [Source: Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

The king or emperor was the supreme religious officer of the state; but he was assisted by other persons, whom he appointed for special religious duties. To each of the three great national gods — Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus — was assigned a special priest, called a flamen. To keep the fires of Vesta always burning, there were appointed six vestal virgins, who were regarded as the consecrated daughters of the state. Special pontiffs, under the charge of a pontifex maximus, had charge of the religious festivals and ceremonies; and the fetiales were intrusted with the formality of declaring war. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

Nina C. Coppolino wrote: “After Actium, when Augustus was given the power of creating new patricians, the supply of men for priesthoods was increased. Augustus himself became a member of the Fratres Arvales, an elite fraternity which performed time-honored, public sacrifices for the prosperity of the state- family. In 12 B.C. Augustus became pontifex maximus; in 11 B.C. , a new high priest of Jupiter, the flamen dialis, was appointed. When Augustus in 8 B.C. divided Rome into fourteen regions, the humble worship by the poor of the gods of the crossroads, the Lares Compitales, was elevated to official stature; this worship was promoted throughout the regions of Rome and Italy in association with the worship of the genius of Augustus. At this time the genius of Augustus was probably included in official oaths. [Source: Nina C. Coppolino, Roman Emperors]

See Separate Article: PRIESTS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

religious procession

Rituals at the Dedication of the Temple of Jupiter

“In 70 A.D. Vespasian ordered the restoration of the Temple of Jupiter the Best and Greatest on the Capitoline Hill. The event was recorded by Tacitus in an account which gives some idea of the ceremonies of the state religion, and its intense conservatism. Tacitus (b.56/57-after 117 A.D.) wrote in A.D. 70: “The work of rebuilding the Capitol was assigned by him to Lucius Vestinius, a man of the Equestrian order, who, however, for high character and reputation ranked among the nobles. The soothsayers whom he assembled directed that the remains of the old shrine should be removed to the marshes, and the new temple raised on the original site. The Gods, they said, forbade the old form to be changed. [Source: Tacitus: “Histories,” Book 4. liii., Translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb. Full text online at classics.mit.edu/Tacitus]

“On the 21st of June, beneath a cloudless sky, the entire space devoted to the sacred enclosure was encompassed with chaplets and garlands. Soldiers, who bore auspicious names, entered the precincts with sacred boughs. Then the vestal virgins, with a troop of boys and girls, whose fathers and mothers were still living, sprinkled the whole space with water drawn from the fountains and rivers. After this, Helvidius Priscus, the praetor, first purified the spot with the usual sacrifice of a sow, a sheep, and a bull, and duly placed the entrails on turf; then, in terms dictated by Publius Aelianus, the high-priest, besought Jupiter, Juno, Minerva, and the tutelary deities of the place, to prosper the undertaking, and to lend their divine help to raise the abodes which the piety of men had founded for them.

“He then touched the wreaths, which were wound round the foundation stone and entwined with the ropes, while at the same moment all the other magistrates of the State, the Priests, the Senators, the Knights, and a number of the citizens, with zeal and joy uniting their efforts, dragged the huge stone along. Contributions of gold and silver and virgin ores, never smelted in the furnace, but still in their natural state, were showered on the foundations. The soothsayers had previously directed that no stone or gold which had been intended for any other purpose should profane the work. Additional height was given to the structure; this was the only variation which religion would permit, and the one feature which had been thought wanting in the splendour of the old temple.”

Activities at Greco-Roman Temples

bird ritual performed a priest

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Hellas” ( c. A.D. 175): “They say that someone uninvited entered the shrine of Isis at Tithorea and died soon after...I heard the same thing from a Phoenician in regard to a temple of Isis at Coptos. [Source: Pausanias, Pausanias' Description of Greece, translated by A. R. Shilleto, (London: G. Bell, 1900)

Strabo wrote in “Geographia,” (c. 20 A.D.) about Greece around 550 B.C: “And the temple of Aphrodite in Corinth was so rich that it owned more than a thousand temple slaves — prostitutes — whom both free men and women had dedicated to the goddess. And therefore it was also on account of these temple-prostitutes that the city was crowded with people and grew rich; for instance, the ship captains freely squandered their money, and hence the proverb, "Not for every man is the voyage to Corinth."”

Philo Judaeus wrote in “De Providentia” (c. A.D. 20): “At Ascalon, I observed an enormous population of doves in the city-squares and in every house. When I asked the explanation, I was told they belonged to the great temple of Ascalon — where one can also see wild animals of every description, and it was forbidden by the gods to catch them.” [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed. “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-1913), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 268, 289]

Plutarch wrote in “Moralia” (c. A.D. 110): “It's not the abundance of wine or the roasting of meat that makes the joy of sharing a table in a temple, but the good hope and belief that the god is present in his kindness and graciously accepts what is offered. [Source: Plutarch, Moralia, translated by Philemon Holland, (London: J.M. Dent, 1912).

1 Corinthians 8 (c. A.D. 56) from the New Testament reads: “So about the eating of meat sacrificed to idols, we know that "there is no idol in the world," and that "there is no God but one." ...But not all have this knowledge. There are some who have been so used to idolatry up until now that, when they eat meat sacrificed to idols, their conscience, which is weak, is defiled.....If someone sees you, with your knowledge, reclining at table in the temple of an idol, may not his conscience, too, weak as it is, be "built up" to eat the meat sacrificed to idols?

Temples were also places that people made wishes and requests to the Gods, and in turn offered thanks if their requests were granted: Some temple inscriptions read:

1) Thanks to Minerva, that she restored my hair.

2) Thanks to Jupiter Leto, that my wife bore a child.

3) Thanks to Zeus Helios the Great Sarapis, Savior and Giver of wealth.

4) Thanks to Silvanus, from a vision, for freedom from slavery.

5) Thanks to Jupiter, that my taxes were lessened.

6) I pray for the safety of my colony and its senate and people, because Jupiter Best and Greatest by his numen tore out and rescued the names of the decurions that had been fixed to monuments by the unspeakable crime of that most wicked city-slave who refused to work. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed.,”The Library of Original Sources”, (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vols. II: The Greek World & III: The Roman World; The Bible (Douai-Rheims Version), (Baltimore: John Murphy Co., 1914)

Personal Piety, Mystery Cult Membership and Talisman

sacrifice procession

On personal piety in Rome, Lucius Apuleius (c.123-c.170 A.D.) wrote in Apologia 55-6: “ I might discourse at greater length on the nature and importance of such accusations, on the wide range for slander that this path opens for Aemilianus, on the floods of perspiration that this one poor handkerchief, contrary to its natural duty, will cause his innocent victims! But I will follow the course I have already pursued. I will acknowledge what there is no necessity for me to acknowledge, and will answer Aemilianus' questions. You ask, Aemilianus, what I had in that handkerchief. Although I might deny that I had deposited any handkerchief of mine in Pontianus' library, or even admitting that it was true enough that I did so deposit it, I might still deny that there was anything wrapped up in it. [Source: “Apologia and Florida Of Apuleius of Madaura, translated by H.E.. Butler Fellow of New College, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1909, gutenberg.org]

If I should take this line, you have no evidence or argument whereby to refute me, for there is no one who has ever handled it, and only one freedman, according to your own assertion, who has ever seen it. Still, as far as I am concerned I will admit the cloth to have been full to bursting. Imagine yourself, please, to be on the brink of a great discovery, like the comrades of Ulysses who thought they had found a treasure when they stole the bag that contained all the winds. Would you like me to tell you what I had wrapped up in a handkerchief and entrusted to the care of Pontianus' household gods? You shall have your will.

“I have been initiated into various of the Greek mysteries, and preserve with the utmost care certain emblems and mementoes of my initiation with which the priests presented me. There is nothing abnormal or unheard of in this. Those of you here present who have been initiated into the mysteries of father Liber alone, know what you keep hidden at home, safe from all profane touch and the object of your silent veneration. But I, as I have said, moved by my religious fervour and my desire to know the truth, have learned mysteries of many a kind, rites in great number, and diverse ceremonies.

This is no invention on the spur of the moment; nearly three years since, in a public discourse on the greatness of Aesculapius delivered by me during the first days of my residence at Oea, I made the same boast and recounted the number of the mysteries I knew. That discourse was thronged, has been read far and wide, is in all men's hands, and has won the affections of the pious inhabitants of Oea not so much through any eloquence of mine as because it treats of Aesculapius. Will any one, who chances to remember it, repeat the beginning of that particular passage in my discourse? You hear, Maximus, how many voices supply the words. I will order this same passage to be read aloud, since by the courteous expression of your face you show that you will not be displeased to hear it. (The passage is read aloud.)

sacrifice table

“Can any one, who has the least remembrance of the nature of religious rites, be surprised that one who has been initiated into so many holy mysteries should preserve at home certain talismans associated with these ceremonies, and should wrap them in a linen cloth, the purest of coverings for holy things? For wool, produced by the most stolid of creatures and stripped from the sheep's back, the followers of Orpheus and Pythagoras are for that very reason forbidden to wear as being unholy and unclean. But flax, the purest of all growths and among the best of all the fruits of the earth, is used by the holy priests of Egypt, not only for clothing and raiment, but as a veil for sacred things. And yet I know that some persons, among them that fellow Aemilianus, think it a good jest to mock at things divine.

For I learn from certain men of Oea who know him, that to this day he has never prayed to any god or frequented any temple, while if he chances to pass any shrine, he regards it as a crime to raise his hand to his lips in token of reverence. He has never given firstfruits of crops or vines or flocks to any of the gods of the farmer, who feed him and clothe him; his farm holds no shrine, no holy place, nor grove. But why do I speak of groves or shrines? Those who have been on his property say they never saw there one stone where offering of oil has been made, one bough where wreaths have been hung.

As a result, two nicknames have been given him: he is called Charon, as I have said, on account of his truculence of spirit and of countenance, but he is also—and this is the name he prefers—called Mezentius, because he despises the gods. I therefore find it the easier to understand that he should regard my list of initiations in the light of a jest. It is even possible that, thanks to his rejection of things divine, he may be unable to induce himself to believe that it is true that I guard so reverently so many emblems and relics of mysterious rites. I care not a straw what Mezentius may think of me; but to others I make this announcement clearly and unshrinkingly. If any of you that are here present had any part with me in these same solemn ceremonies, give a sign and you shall hear what it is I keep thus. For no thought of personal safety shall induce me to reveal to the uninitiated the secrets that I have received and sworn to conceal.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024