ANCIENT EGYPTIAN EDUCATION

scribe Most people were illiterate. Most of people that learned to read or were educated were nobles and scribes.

Educated Egyptians often learned to read at the age of four. The pharaohs went to the equivalent of exclusive private schools with the children of government officials, nobility and bureaucrats. The students learned to recognize and pronounce several hundred hieroglyphics, then they were taught arithmetic and finally writing. A writing kit consisted of reeds and a palette of solid inks. Papyrus, the material they wrote on, was made was made of the pressed fibrous material of a plant, and only the richest people in Egypt could afford it.♀

Scribe school could be pretty tough. Describing his methods one instructor wrote: “The ear of a boy is on his back. He listens when he is beaten.” After school, in their free time, young Egyptian nobles wrestled and swam in the Nile. If they were good their fathers taught them how to hunt hare, gazelle, ibex and antelope.♀

See Separate Article: SCHOOLS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: CURRICULUM, TEACHING METHODS, COPY BOOKS africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Childhood in Ancient Egypt” by Amandine Marshall and Colin Clement (2022) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

“The Teachings of Ptahhotep: The Oldest Book in the World” by Ptahhotep (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Wisdom Texts” by Muata Ashby (2006) Amazon.com;

“Gymnastics of the Mind: Greek Education in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt”

by Raffaella Cribiore (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Loyalist Teaching": an important teaching text: “Loyalist Teaching Sehetepibra: Hieroglyph text and English translation by Frederick Lauritzen (2020) . Amazon.com;

“Instructions of Amenemhat" is another important teaching text;

“Ancient Egyptian Scribes: A Cultural Exploration” by Niv Allon and Hana Navratilova | (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Language and Writing: The History and Legacy of Hieroglyphs and Scripts in Ancient Egypt” by Charles River Editors (2019) Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

Importance of Education in Ancient Egypt

When the wise Dauuf, the son of Chert'e, voyaged up the Nile with his son Pepi, to introduce him into the “court school of books," he admonished him thus: “Give thy heart to learning and love her like a mother, for there is nothing that is so precious as learning. " Whenever or wherever we come upon Egyptian literature, we find the same enthusiastic reverence for learning (or as it is expressed more concretely, for books). If however, we expect to find ideal motives for this high estimation of learning, we shall be disappointed. The Egyptian valued neither the elevating nor ennobling influence which the wise men of antiquity imputed to him, and still less the pure pleasure which we of the modern world feel at the recognition of truth. The wise Dauuf himself gives us the true answer to our questions on this subject; after he has described in well-turned verses all the troubles and vexations of the various professions, he concludes in favor of wisdom in the last two lines, which have been frequently quoted by later writers: “Behold there is no profession which is not governed, It is only the learned man who rules himself. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The Egyptians valued learning because of the superiority which, in matters of this life, learned men possessed over the unlearned; learning thus divided the ruling class from those who were ruled. He who followed learned studies, and became a scribe had put his feet on the first rung of the great ladder of official life, and all the offices of the state were open to him. He was exempted from all the bodily work and trouble with which others were tormented. The poor ignorant man, “whose name is unknown, is like a heavily-laden donkey, he is driven by the scribe," while the fortunate man who “has set his heart upon learning, is above work, and becomes a wise prince." Therefore “set to work and become a scribe, for then thou shalt be a leader of men. The profession of scribe is a princely profession, his writing materials and his rolls of books bring pleasantness and riches. "

The scribe never lacks food, what he wants is given to him out of the royal store: “the learned man has enough to eat because of his learning." He who is industrious as a scribe and does not neglect his books, he may become a prince, or perhaps attain to the council of the thirty, and when there is a question of sending out an ambassador, his name is remembered at court. "If he is to succeed, however, he must not fail to be diligent, for we read in one place: the scribe alone directs the work of all men, but if the work of books is an abomination to him, then the goddess of fortune is not with him. "

Therefore he who is wise will remain faithful to learning, and will pray Thoth the god of learning to give him understanding and assistance. Thoth is the “baboon with shining hair and amiable face, the letter writer for the gods," he will not forget his earthly colleagues if they call upon him and speak thus to him: “Come to me and guide me, and make me to act justly in thine office. Thine office is more beautiful than all offices. . . . Come to me, guide the god thoth me! I am a servant in thine house. Let all the world tell of thy might, that all men may say: ' Great is that animal. which Thoth hath done. ' Let them come with their 'children, to cause them to be marked as scribes. Thine office is a beautiful office, thou strong protector. It rejoices those who are invested with it.' "

High Status of Educated People in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “Judging from the various references to education and literacy made in Egyptian literary works, one could deduce that being a school graduate was, indeed, highly esteemed in Egyptian society. An example of such references made in Egyptian “Instructions” (that is, didactic works mostly ascribed to a famous sage and discussing, in the form of short sayings and admonitions, general matters of life and moral principles) is: ‘One will do all you say, If you are versed in writings; Study the writings, put them in your heart, Then all your words will be effective. Whatever office a scribe is given, He should consult the writings.’ [The Instruction of Any, lines 7,4 - 7,5] [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The general style of such literary references to education is well illustrated in this example: education is praised in connection with the scribal profession and its high status in Egyptian society. Hence, one may say that such references are really made by scribes (that is, the authors of such compositions) about the value of their own profession, addressing other scribes or students who are to follow the scribal profession. In other words, this is probably a dialogue between members of the same circle, reflecting little about the general appreciation of education among members of Egyptian society who have not gone through a scribal training.

Education and Apprenticeship in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “The main purpose of education and apprenticeship in ancient Egypt was the training of scribes and of specialist craftsmen. The result of this profession-oriented educational system was restricted accessibility to schooling, most probably favoring male members of the Egyptian elite. Basic education offered in Egyptian local schools consisted of the teaching of language, mathematics, geography, and of other subjects appropriate for the preparation of potential scribes who were destined to work in local and national Egyptian institutions, such as the palace or the temples. The evidence for the existence of such an educational system in ancient Egypt comes mainly in the form of school exercises, schoolbooks, and references found in literary and documentary texts. There is comparatively less evidence, however, for the role of apprenticeship, which was a pedagogical method employed mainly for the training of craftsmen or for advanced and specialized education, such as that needed to become a priest. Although the main elements of pedagogy probably remained as such throughout Egyptian history, it is likely that foreign languages were taught from the New Kingdom onwards, culminating in the bilingual Egyptian-Greek education of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Like modern educational systems, ancient Egyptian education prepared the young members of middle and upper classes for entering the labor force of the country and actively participating in various professions and duties related to the civil, priestly, and military spheres. However, unlike education nowadays, the Egyptian school system mainly offered basic and rarely advanced training. Hence, there was probably no Egyptian equivalent to a modern university with its broad educational horizons and its large diversity of specializations. Also, unlike modern educational standards according to which schooling is in most countries a prerequisite for most professions and careers, the Egyptian local school focused primarily on the preparation of scribes and officials before they joined the complex system of local or national bureaucracy. Together with the priesthood, these were the main, highly- esteemed professions available for those who completed schooling.

“The narrow perspectives Egyptian schooling kept resulted in a limited curriculum and probably also in limited approaches to study material. Although such limitations would suggest a canonized model for Egyptian education, its program and curricula most likely allowed considerable space for local variation—given that there was no central authority for controlling the function of Egyptian schools, since there is no evidence that the palace was much involved in the shaping and maintenance of schools. The lack of a nationally organized system in schooling probably also resulted in education’s minor involvement in the building of a national identity for Egyptian students. By contrast, modern educational systems are designed and checked by the national authorities and are meant to contribute to the shaping and maintenance of a national identity.

“When one attempts to discover and re- construct the educational system of an ancient civilization, one seeks, first, evidence for the existence of schools. This can be in the form of: a) archaeological traces of school activity in specific localities; b) products of school activity, such as schoolbooks or school exercises; and c) references to specific schools or to a more general school education in literary or documentary texts. Second, in order to better understand the way the educational system functioned within an ancient society, one can try to identify the locality of specific schools, examining their spatial relationship with a nearby community or other institutions. In this way, one can consider the schools’ potential contact with other aspects of an ancient society, as well as their potential role in the life and development of that society.”

Education Versus Apprenticeship in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “The term “education” is used here, as in most related Egyptological studies, to denote a social institution (or an educational system) rather than a general idea encompassing all forms of teaching and learning. Thus, by definition, the study of ancient Egyptian education excludes the upbringing of children at home. The main reason for this exclusion is that there is very limited evidence for the way children were educated at home and for the relationship between home and school education. However, it must be noted that home education was probably a pedagogical method as important as schooling. The majority of the working population, including agricultural workers and local craftsmen, probably received their training within a domestic context, rather than at school. The existence of such a household/family-related training context is implied in evidence from Deir el- Medina, suggesting family connections between various groups of craftsmen (cf. the studies on woodcutters and potters). The same may have applied, to a certain extent, even to scribe candidates, since family relations between succeeding scribes are widely attested. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The study of ancient Egyptian education focuses on the function of the Egyptian schools, which aimed at providing the youth with a basic knowledge in a variety of subjects, such as language and mathematics, as well as at teaching ethics and rules of everyday conduct. The main term employed to denote “education” in the ancient Egyptian language read sbAyt and meant “instruction” with a connotation of “punishment”. This was the same term that featured in the titles of Egyptian works of wisdom known as “Instructions”—a fact that may suggest a pedagogical use of such literary works. Along with sbAyt, the term mtrt was also employed to denote the sense of “instruction,” this time with a connotation of “witnessing” or “personal experience.” The latter term was mainly used in the Late Period, but a semantic difference between mtrt and sbAyt has not been detected.

“In contrast to “education,” whose conventional definition, in the case of this essay, covers aspects of basic training received at school, “apprenticeship” is a term that usually refers to a specific method of instruction, namely the instruction offered by a single teacher to a single or a small number of students on one or more specialized subjects or skills. This was a very popular educational method that was employed mainly when advanced training was sought out in order to develop some of the aspects of the curricula of Egyptian schools, such as writing or mathematics, or to introduce new subjects and skills, such as the study of religious texts or the learning of a craft. In addition, apprenticeship was a manner of instruction that was probably also used in some local Egyptian schools even for basic training— perhaps due to the small number of teachers and students available.

“The term most probably denoting apprenticeship read Xrj-a, which literally meant “under the arm/control of,” while the expertteacher was called either nb, “master,” or jtj, “father.” The latter is a term employed mainly in literary contexts to imply a close father-son relationship for that between an instructor and his audience. Thus, for instance, the title “father” is often used in didactic texts, denoting the author of the instruction and teacher of an audience that has still much to learn: ‘Beginning of the sayings of excellent discourse spoken by the Prince….Ptahhotep, in instructing the ignorant to understand and be up to the standard of excellent discourse…So he spoke to his son.’ [Instruction of Ptahhotep]”

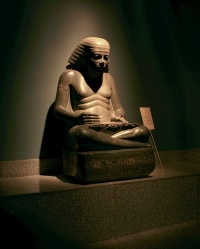

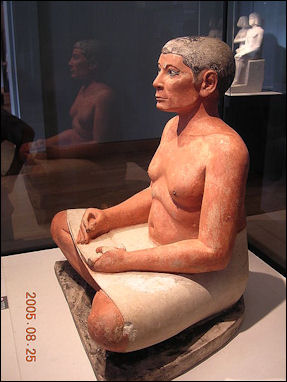

Ancient Egyptian Scribes

Much of Ancient Egyptian education was oriented towards scribes. Being a scribe in ancient Egypt was a high-status position in ancient Egypt, especially since only 1 percent to 5 percent of the ancient Egyptian population could read and write, according to the University College London. The ancient Egyptians believed that writing was invented by the ibis headed god Thoth and that words had magical powers.

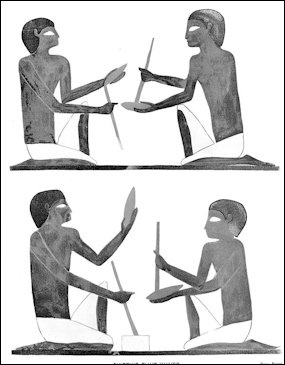

Scribes belonged to a caste. When students were being taught by the fathers they practiced their hieroglyphics on stones and potsherds before they wrote on papyrus. Describing the importance of the profession one ancient Egyptian poet wrote: "It's the greatest of all calling/ Thee is none like it in the land/Set your heart on books!/...There's nothing better than books!" "See, there's no profession without a boss/ Except for the scribe ; he is the boss." [Source: David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

One papyrus, translated by Miriam Lichtheim, says, ''Happy is the heart of him who writes; he is young each day ... Be a scribe! Your body will be sleek, your hand will be soft ... You are one who sits grandly in your house; your servants answer speedily; beer is poured copiously; all who see you rejoice in good cheer.''

See Separate Article: SCRIBES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Female Education and Literacy in Ancient Egypt

“In the Old and Middle Kingdoms, middle and upper class women are occasionally found in the textual and archaeological record with administrative titles that are indicative of a literate ability. In the New Kingdom the frequency at which these titles occur declines significantly, suggesting an erosion in the rate of female literacy at that time (let alone the freedom to engage in an occupation). However, in a small number of tomb representations of the New Kingdom, certain noblewomen are associated with scribal palettes, suggesting a literate ability. Women are also recorded as the senders and recipients of a small number of letters in Egypt (5 out of 353). However, in these cases we cannot be certain that they personally penned or read these letters, rather than employed the services of professional scribes. -

“Many royal princesses at court had private tutors, and most likely, these tutors taught them to read and write. Royal women of the Eighteenth Dynasty probably were regularly trained, since many were functioning leaders. Since royal princesses would have been educated, it then seems likely that the daughters of the royal courtiers were similarly educated. In the inscriptions, we occasionally do find titles of female scribes among the middle class from the Middle Kingdom on, especially after the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, when the rate of literacy increased throughout the country. The only example of a female physician in Egypt occurs in the Old Kingdom. Scribal instruction was a necessary first step toward medical training. -

Legacy of Ancient Egyptian Education on the Post-Pharaonic Era

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “Historical developments in the educational system of ancient Egypt were probably closely linked to developments in Egyptian language. As mentioned above, hieratic, which was most likely the first script an Egyptian pupil was taught, was replaced at some point during the fourth century B.C. by Demotic. This change took place at the beginning of the Hellenistic era, during which Greek became the official language of the palace in Alexandria. Therefore, in terms of administration, Demotic and Greek co-existed and were used on different occasions, making their mastery a significant requirement for those who wanted to climb the social ladder in Hellenistic and, later, Roman Egypt. As a result, probably most of the local Egyptian schools of those eras added Greek to their curricula. In addition, Greek didaskaleia (“schools”) along with gymnasia (“sport schools”) were founded at most of the sites of Hellenistic and Roman Egypt, as in Alexandria, Antinoopolis, or Krokodilopolis, which included large non- Egyptian populations . The relationship between the Greek gymnasia and the Egyptian schools is not clear, but it seems they were attracting ethnically and/or socially different groups. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“As Demotic was replaced by Coptic from the second century CE onwards and the usage of Egyptian language retreated from the areas of administration and trade, in which Greek and Latin were used instead, the number of schools teaching in Egyptian probably decreased and were limited to Christian monasteries that took over the task of maintaining and developing Coptic language and literature.

“As far as the function of apprenticeship in the post-Pharaonic era is concerned, there is some evidence for children becoming apprentices to experienced craftsmen. Thus, for instance, contracts exist between such craftsmen and parents who sent their children off to learn a craft like weaving or playing a musical instrument. One of these contracts written in Greek and dated to 10 CE reads: “.we will produce our brother named Pasion to stay with you one year from the 40th year of Caesar and to work at the weaver's trade, and...he shall not sleep away or absent himself by day from Pasonis’ house.” [Papyrus Tebtunis 0384]” Peter A. Piccione wrote: “It is uncertain, generally, how literate the Egyptian woman was in any period. Baines and Eyre suggest very low figures for the percentage of the literate in the Egypt population, i.e., only about 1 percent in the Old Kingdom (i.e., 1 in 20 or 30 males). Other Egyptologists would dispute these estimates, seeing instead an amount at about 5-10 percent of the population. In any event, it is certain that the rate of literacy of Egyptian women was well behind that of men from the Old Kingdom through the Late Period. Lower class women, certainly were illiterate; middle class women and the wives of professional men, perhaps less so. The upper class probably had a higher rate of literate women. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024