ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TRANSPORTATION

carrying stuff on foot Most people got around on foot. Animals and wheeled vehicles were not widely used. Most goods and people traveled by river. Cattle, stone, grain and cedar from Lebanon were brought to Egyptian cities by Nile ships. A perfect scale model of a working glider was discovered in 2,000-year-old Egyptian tomb.

Owing to the long serpent-like form of Egypt, the distances between most of the towns were of a disproportionate length; this intercourse was therefore always of a limited nature. The distance from Thebes to Memphis was about 550 kilometers (340 miles), from Thebes to Tanis about 700 kilometers (435 miles), and from Elephantine to Pelusium as much as 940 kilometers (585 miles).

The Semitic Hyksos who briefly ruled Egypt introduced the horse and chariot around 1700 B.C. When hooked up to a pair of horses, an Egyptian chariot, weighing only 17 pounds, could easily reach speeds of 20 miles-per-hour (compared to two miles-per-hour with oxen). The chariots enabled the Egyptians to expand their empire. Camels were not introduced to Egypt until around 200 B.C. Until then donkey caravans were used to bring gold, ebony, ivory, rare stones for statues, incense and panther skins.

“Egypt is a large country. The distance along the Nile from the Mediterranean coast to the First Cataract is about 1,100 kilometers, or about 660 miles, and the straight-line distance from the Red Sea coast to the site of ancient Koptos, where overland transport routes from the Red Sea to the Nile Valley historically converged, is about 90 miles or145 kilometers. Egyptian merchants, messengers, and armies frequently traveled beyond the borders of Egypt to areas in which they had interests, especially Syria- Palestine and Nubia. Therefore, in order for Egypt to maintain cultural, political, and economic cohesion, reliable transportation was essential.”

RELATED ARTICLES: TRAVEL IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com ; LIVESTOCK AND DOMESTICATED ANIMALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Transport in Ancient Egypt” by Robert B. Partridge (1996) Amazon.com;

“Wheeled Vehicle and Ridden Animals in the Ancient Near East” by M. A. Littauer and J. H. Crouwel Amazon.com;

“Chariots in Ancient Egypt: The Tano Chariot, A Case Study”

by Dr. Andre J. Veldmeijer and Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Nile: History's Greatest River” by Terje Tvedt (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Nile: Traveling Downriver Through Egypt's Past and Present” by Toby Wilkinson (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Gift of the Nile?: Ancient Egypt and the Environment (Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections) by Egyptian Expedition, Thomas Schneider, Christine L. Johnston (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Nile and Ancient Egypt: Changing Land- and Waterscapes, from the Neolithic to the Roman Era”, Illustrated by Judith Bunbury (2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Ships and Shipping” by William Franklin Edgerton (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (1995) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Boats and Ships” by Steve Vinson (2008) Amazon.com;

“A Categorisation and Examination of Egyptian Ships and Boats from the Rise of the Old to the End of the Middle Kingdoms by Michael Allen Stephens (2012) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Boats and Ships” by Sean McGrail (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ship 17 a Baris from Thonis-Heracleion” (Ships and boats of the Canopic Region in Egypt) by Alexander Belov (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Water Transportation in Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt — which for the most part consisted of a narrow valley of a great river — that river becomes the natural highway for all communication, especially when, as in Egypt, the country is difficult to traverse throughout a great part of the year. The Nile and its canals were the ordinary roads of the Egyptians; baggage of all kinds was carried by boat, all journeys were undertaken by water, and even the images of the gods went in procession on board the Nile boats — how indeed should a god travel except by boat? [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Boats and ships were used for water travel. For journeys on water, vessels were used as early as the fifth millenium B.C.. They were an essential element of the Egyptian traffic system. A wide variety of ships and boats was used for transporting freight and passengers on inland waterways and at sea.

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: ““Boats in ancient Egypt were ubiquitous and crucially important to many aspects of Egyptian economic, political, and religious/ideological life. Four main categories of uses can be discussed: basic travel/transportation, military, religious/cere- monial, and fishing. Examples of each can be traced from the formative period of Egyptian history down to the close of Egypt’s traditional culture in the fourth century CE. One terminological problem is to identify a dividing line between “boats” and “ships.” For the purpose of this article, the term “ship” is arbitrarily taken to mean craft working entirely or primarily at sea (i.e., on the Red Sea or Mediterranean). Therefore, we confine ourselves here as far as possible to water craft of any size that were intended primarily for service on the Nile.” [Source:Steve Vinson, University of Indiana, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SHIPS AND BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RIVER TRANSPORT AND USES OF BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SEA TRAVEL IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MERER'S DIARY: 4,600-YEAR-OLD LOGBOOK ABOUT PYRAMID BOATMEN africame.factsanddetails.com

Land Transportation in Ancient Egypt

donkeys carrying stuffTraveling by land in Egypt was quite an unimportant matter compared to river traveling. Long journeys were thought to have generally been made by water; it was only for the short distances from the Nile to their destination that the Egyptians required other means of conveyance. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “For land transportation, attested methods include foot-traffic and the use of draft animals— especially donkeys and oxen, but also, from the first millennium B.C. onward, camels. Land vehicles, including carts, chariots, sledges, and carrying chairs, were dependent on the existence and nature of suitable routes, some of which may have been improved or paved along at least part of their extent. The transport of large objects, especially stone blocks, obelisks, and statues, required specialized techniques, infrastructure, and vehicles. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

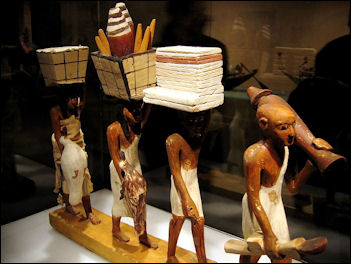

Heidi Köpp-Junk of Universität Trier wrote: “ For overland transport, pack animals were used as well as vehicles. The heaviness of the load influenced the means of transportation chosen. Lighter objects, such as luggage or supplies, were carried by the traveler himself or by servants, occasionally with the help of poles, such as are mentioned in the text of an expedition to Wadi Hammamat, and perhaps of yokes, as depicted in a hunting scene in Beni Hassan. Slightly heavier weight was transported by animals. The donkey was the typical pack animal of ancient Egypt, whereas the ox was the typical draft animal. Overland transport of heavier loads took place with vehicles such as sledges, carts, and wagons.” [Source: Heidi Köpp-Junk, Universität Trier, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

See Separate Articles: LAND TRANSPORT IN ANCIENT EGYPT: CARRIAGES, LITTERS, CARTS, CHARIOTS africame. factsanddetails.com

Means of Transportation in Ancient Egypt

Heidi Köpp-Junk of Universität Trier wrote: “As means of overland travel, mount animals, sedan chairs, or chariots are known—and of course walking. For donkey riding, indirect evidence exists from the Old King-dom in the form of representations of oval pillow- shaped saddles depicted in the tombs of Kahief, Neferiretenef , and Methethi. These saddles were similar to the saddle of the Queen of Punt depicted in a New Kingdom scene in the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri. Similarly, representations of donkey riding are known from the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom. The earliest pictorial evidence of a ridden horse dates to the reign of Thutmose III. Horse riding is proven in connection with scouts, couriers, and soldiers and is a mode of locomotion that had an obvious emphasis on speed.” [Source: Heidi Köpp-Junk, Universität Trier, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Road in Giza used to transport stones to the Pyramids

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “Egypt’s most important, most visible, and best-documented means of transportation was its watercraft. However, pack animals, porters, wheeled vehicles, sledges, and even carrying chairs were also used to move goods and people across both short and long distances, and each played an important role. The regular transportation of stone from quarries that might lie far from the river, and grain from the countless large and small farms that existed throughout the Nile Valley, also required the organization and maintenance of integrated transportation facilities and networks that involved both land and water transport. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Donkey and, later, camel caravans seem to have been the preferred mode of transport for goods along roads and tracks, as Pharaonic texts such as Harkhuf’s autobiography and the Tale of the Eloquent Peasant suggest, and as archaeological evidence—for example, the donkey hoof- prints from the Toshka gneiss-quarry road mentioned above—shows. The period in which the camel was introduced into, and domesticated in, Egypt remains controversial. Most faunal, iconographic, and textual evidence points to a date sometime in the first millennium B.C., but some have argued for an introduction of the camel as early as the Predynastic Period. The question is complicated because faunal or iconographic evidence for the presence of camels does not necessarily prove camel domestication.”

Roads in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “Although land transportation is less visible to us in the iconographic record than travel by boats or ships, there is an abundant and growing archaeological inventory of formal roads and informal overland routes that show the crucial importance of land transport for the functioning of Egypt’s economy and culture. In the area of the flood-plain itself, ancient routes are often difficult to trace, with the exception of paved, ceremonial roads like the avenue of sphinxes linking the Karnak and Luxor temples. The ubiquity of canals, basins, and dykes will certainly have complicated land-travel, particularly during flood season; although dykes will also have provide raised routes that could be traversed to avoid fields, especially in times of high water. Outside of the flood plain, archaeological exploration of Egypt’s desert transportation networks is an extremely promising field. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Comparatively few paved roads have been discovered from Pharaonic Egypt, but they are not unknown: a paved road linking Widan al-Faras and Qasr al-Sagha in the northern Fayum appears to have been constructed in the early third millennium B.C., and was described as the world’s earliest paved road. The road, 2.4 meters wide, was paved with slabs of sandstone and logs of petrified wood. Another early paved road was constructed to link quarries at Abusir to the Fifth Dynasty pyramids about 1.2 kilometers away. This more-substantial road was approximately ten meters (or 20 cubits) wide, built on a 30- centimeter-deep bed of mud-brick and local clay, and finished off with a paving of field- stones mortared together with clay.

“Although road surfaces were not often paved along their entire route, stone fill at least may have been used to even out the surface of a path; one example comprises the stone causeways constructed on a 17- kilometer route linking Amarna and Hatnub. Over relatively short distances, reinforced and stabilized tracks for hauling heavy loads of stone to pyramid construction sites were laid using heavy wooden members from derelict ships, then covering them over with limestone chips and mortar. In other cases, roads might simply consist of a track systematically cleared of gravel and debris, and marked with stelas, cairns, and campsites.

RELATED ARTICLES: INFRASTRUCTURE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: ROADS, COMMUNICATION, WATER TUNNELS africame.factsanddetails.com

map of the Pyramids area

Ancient Egyptian Trade Routes

John Noble Wilford wrote in New York Times, “Over the last two decades, John Coleman Darnell and his wife, Deborah, hiked and drove caravan tracks west of the Nile from the monuments of Thebes, at present-day Luxor. On these and other desolate roads, beaten hard by millennial human and donkey traffic, the Darnells found pottery and ruins where soldiers, merchants and other travelers camped in the time of the pharaohs. On a limestone cliff at a crossroads, they came upon a tableau of scenes and symbols, some of the earliest documentation of Egyptian history. Elsewhere, they discovered inscriptions considered to be one of the first examples of alphabetic writing.[Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, September 6, 2010]

The explorations of the Theban Desert Road Survey, a Yale University project co-directed by the Darnells, called attention to the previously underappreciated significance of caravan routes and oasis settlements in Egyptian antiquity. In August 2010, the Egyptian government announced what may be the survey’s most spectacular find: the extensive remains of a settlement — apparently an administrative, economic and military center — that flourished more than 3,500 years ago in the western desert 110 miles west of Luxor and 300 miles south of Cairo. No such urban center so early in history had ever been found in the forbidding desert.

Finding an apparently robust community as a hub of major caravan routes, Dr. John Darnell, a professor of Egyptology at Yale, said, should “help us reconstruct a more elaborate and detailed picture of Egypt during an intermediate period” after the so-called Middle Kingdom and just before the rise of the New Kingdom.At this time, Egypt was in turmoil. The Hyksos invaders from southwest Asia held the Nile Delta and much of the north, and a wealthy Nubian kingdom at Kerma, on the Upper Nile, encroached from the south. Caught in the middle, the rulers at Thebes struggled to hold on and eventually prevail. They were succeeded by some of Egypt’s most celebrated pharaohs, such notables as Hatshepsut, Amenhotep III and Ramses II.

See Separate Article: TRADE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Transporting Goods in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “Among the most important and most difficult items to transport in Egypt were large cargoes of stone and wood for monumental building projects, and large cargoes of grain collected as in-kind taxation and turned over to the state or to the temples. The transportation of both classes of cargo called for an integrated transportation system that combined both land- and river-transport, including the construction and maintenance of specialized infrastructure and vehicles. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Vessel accounts and tomb illustrations illustrate a wide variety of cargoes on Nile vessels: gold, bricks, sand, reeds, cattle, fish, bread, cabbage, fruit, slaves, and tomb- robbery loot are all placed aboard. Exotic, high- prestige products from the Near East, Europe, and Africa imply far-flung and complex transport networks involving sea-going shipping, land-transport within and beyond Egypt itself, and Nile-river shipping.

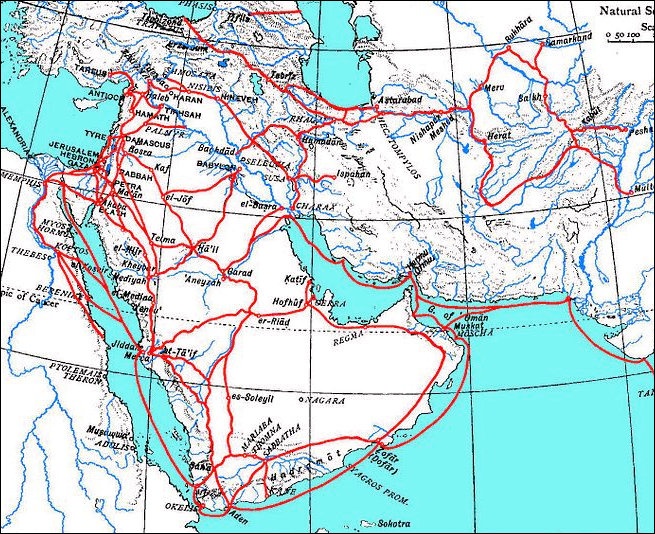

Middle Eastern trade routes in antiquity

“Arrival of exotic tribute from sub-Saharan Africa is famously portrayed in the Eighteenth Dynasty tomb of Huy, viceroy of Nubia under Tutankhamen, and the Sixth Dynasty tomb autobiography of Harkhuf illustrates not only donkey-caravan-based trade with the area of what is now Sudan, but also includes a copy of a letter to Harkhuf from the child-king Pepy II, excited over the impending arrival of a pygmy at the Egyptian court. Young Pepy’s pygmy suggests Egypt’s connections to transport networks that extended deep into tropical Africa, and whose exact nature and extent can only be speculated upon.”

Transporting Grain in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “While wood and stone were important for monumental construction and hence for the prestige of pharaoh and of the gods, the transportation of bulk commodities like grain was of fundamental economic importance and is much more thoroughly documented, especially in the Ramesside and Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. Typically grain would have been hauled, presumably by donkey, from farmsteads to embarkation points, where it would have been accounted for and loaded onto ships by local workers. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Middle-Kingdom granary models, such as the famous model from the tomb of Meket-Ra at Thebes, show individual porters with sacks of grain on their backs, emptying them out one at a time into silos. From there, grain would have eventually been unloaded and placed aboard transport vessels. From the New Kingdom tomb of Paheri at Elkab, a work-song sung by stevedores loading grain onto transport vessels is recorded:

‘Loading the cargo ships

with barley and emmer. They say:

Will we spend the whole day hauling barley and white emmer?

The full silos are overflowing; piles reach their openings.

These ships are heavily loaded; the grain is spilling out.

We are continually hurried on our way. Look, our hearts are made out of bronze!’

“Extensive documentation, particularly from the Twentieth Dynasty, illustrates the process of hauling grain in large quantities. Among the most important documents in this respect is Papyrus Amiens, originally published by Gardiner, and more recently supplemented by a lost portion known as Papyrus Baldwin, published by Janssen. Here we see the records of a flotilla of some 21 vessels that appear to have been engaged in a major tax collection voyage, perhaps in the region of Assiut, where the papyrus itself was found. Each ship made multiple stops, embarking large quantities of grain, which were often accounted for in detail, according to the specific agricultural domain from which the grain came and according to the individual or group who were to be credited with supplying the grain. Occasionally, as in P. Amiens r. 4.1, we see grain transferred between ships, perhaps (but not certainly) due to vessels being disabled. Another important Ramesside papyrus, the “Turin Indictment Papyrus”, is notable for illustrating the opportunities for embezzlement that might present themselves to the operators of transport vessels hauling large amounts of grain.

“The transport of grain in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods in Egypt is extensively documented in Greek papyrological sources. An instructive example is the Ptolemaic-era account papyrus Oxy 3, 522, which describes how boat captains recruited local labor through village elders to load 5,400 artabas (about 170 metric tons). Cargoes were often accompanied by persons known as naukleroi, whose function appears to have been to safeguard the cargo and organize transportation, not actually operate the ships in question. While the owner- operation of transport vessels is attested in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, transport vessels might also owned by wealthy investors, particularly members of the Ptolemaic royal family , or by governmental institutions such as the office of the dioiketes, or finance minister.”

Transportation Costs in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “Payments for transport-vessel crews are sporadically attested in Pharaonic documentation, but precisely what the costs were intended to cover, and how they related to the actual personnel and operational costs involved is seldom if ever made absolutely clear. The best example is the payments recorded in Papyri Amiens and Baldwin. Since the payments bear no obvious relationship to the size of the cargoes, it seems likely that they were related to the size of the crew. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“In Ramesside documentation, specific expenses other than crew expense are seldom accounted for in detail. The Ramesside ship’s log, Papyri Turin 2008 and 2016, includes items like a net, papyrus rope, fish, and water-birds as payments for lower- ranking crew members. In the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, costs for river transportation are better documented. Operational expenses might have typically consumed thirty percent of gross vessel income, with the net divided between crew, owner, and taxes. Crew payments attested in the Ptolemaic Period include the 8.5 drachmas per month for crew members and ten per month for the captain, according to one of several payment plans proposed in the contract P. Cairo Zenon IV 59649.

“Costs of land transport in Roman Egypt are discussed by Adams. One calculation suggests that in the first century CE the transport of 100 artabas (about three metric tons) over a distance of 100 kilometers would cost about 39 drachmas, including six drachmas for donkey drivers. At this price, the cost of transport was between 5 and 13 percent of the value of the wheat itself . The price fluctuated considerably, however, throughout the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods—with monetary inflation and deflation, and with the varying costs of human and animal labor. Those responsible for transporting grain could economize by using their own donkeys, boats, and personnel, rather than hiring labor. In all periods, preserved price data suggest that transport cost per unit of cargo-distance declined as the volume of cargo and distance of transport increased, although this advantage will have been more obvious with the use of large transport vessels, for two reasons: both construction costs and crew requirements as a function of vessel volume declined as vessel volume increased.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024