SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Ancient Egyptian plane? The Egyptians developed fairly sophisticated chemistry through cosmetic-making, dying, glassmaking and gold metallurgy. The word chemistry is derived from the word Alchemy which is the ancient name for Egypt. In ancient times people, sciences such as chemistry, biology and physics did not exist. People believed that natural processes were caused by spirits. Even so, a great deal of practical knowledge was ascertained as properties of metals were observed and processes such as glassmaking and alloy production were figured out.

Ancient Egyptian plane? The Egyptians developed fairly sophisticated chemistry through cosmetic-making, dying, glassmaking and gold metallurgy. The word chemistry is derived from the word Alchemy which is the ancient name for Egypt. In ancient times people, sciences such as chemistry, biology and physics did not exist. People believed that natural processes were caused by spirits. Even so, a great deal of practical knowledge was ascertained as properties of metals were observed and processes such as glassmaking and alloy production were figured out.

Pottery making was well advanced by 3000 B.C. The earliest Egyptian pottery was unglazed red earthenware. Both Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt had the pottery wheel by that time. The potter’s wheel is believed to have been invented in Mesopotamia around 3500 B.C. and may be tied to the invention of wheeled vehicles. See Mesopotamia.

Pottery making was well advanced by 3000 B.C. The earliest Egyptian pottery was unglazed red earthenware. Both Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt had the pottery wheel by that time. The potter's wheel is believed to have been invented in Mesopotamia around 3500 B.C. and may be tied to the invention of wheeled vehicles. See Mesopotamia. Glassmaking was known in ancient Egypt as far back as 2500 B.C. The bottle was invented sometime around 1500 B.C. by Egyptian artisans. Glass from Egypt

The engineering skill of the ancient Egyptians has to be admired. Knowing only the lever, roller, inclined plane and possibly a long copper saw, they erected immense monuments in the desert, such as the Great Pyramid of Cheops, which stands 146 meters (481 ft. high) and contains 2 million limestone blocks, most weighing around 2.5 tons, and quarried several kilometers away and transported presumably on barges and sledges to their present location. [Source: Plumbing & Mechanical Magazine, July 1989, theplumber.com]

The Egyptians used primitive water wheels about 2500 B.C. built canals and irrigation systems. They didn’t make so many roads. Roads were not so important because they relied on the Nile for transportation. In 2300 B.C. the ancient Egyptians built channels through the first cataract of the Nile, where the Aswan Dan stands today. This helped open the way for trade between the Pharaohs and Africa. Messages were sent along the Nile. Seals were the equivalent of signatures. They were applied on wet mud with a paint-roller like cylinder.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com;

BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ;

Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt;

Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ;

British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk;

Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt;

Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ;

Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ;

Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities;

KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com;

Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ;

Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org;

Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation” by Ian Shaw (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Science: Source Book. Volume I: Knowledge and Order” by Marshall Clagett (1989) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Science, Vol. II: Calendars, Clocks, and Astronomy, Memoirs, American Philosophical Society by Marshall Clagett (1995) Amazon.com;

"Ancient Egyptian Science, Vol. III: A Source Book, Ancient Egyptian Mathematics” by Marshall Clagett (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Origins and Use of the Potter’s Wheel in Ancient Egypt” by Sarah Doherty (2015) Amazon.com;

“Lost Technologies of Ancient Egypt: Advanced Engineering in the Temples of the Pharaohs” by Christopher Dunn (2010) Amazon.com;

“Sticks, Stones, and Shadows: Building of the Egyptian Pyramids” by Martin Isler (2001) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy of Ancient Egypt: A Cultural Perspective” by Juan Antonio Belmonte, José Lull, et al. (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Astronomy” by Norman Lockyer (1894) Amazon.com;

“Architecture, Astronomy and Sacred Landscape in Ancient Egypt” by Giulio Magli (2013) Amazon.com;

“Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies” (ReissueEdition) by Daryn Lehoux Amazon.com;

”Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs” by Richard J. Gillings (1982) Amazon.com;

“Mathematics in Ancient Egypt: A Contextual History” by Annette Imhausen (2016) Amazon.com;

“Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt” by Corinna Rossi (2004) Amazon.com;

“Count Like an Egyptian: A Hands-on Introduction to Ancient Mathematics” by David Reimer (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook”

by Victor J. Katz , Annette Imhausen, et al. (2007) Amazon.com;

Measurement in Ancient Egypt

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the oldest known measure is the beqa, used in ancient Egypt as far back as 3800 B.C. These cylindrical weights weighed 6.65 to 7.45 ounces. For measuring weight, the ancients used grains of wheat or barley corns; the grain to this day is one of the smallest units of weight, 1/7000 of a pound. The carat, used in weighing gems, was derived from the tiny carob seed. A deben was an ancient Egyptian measurement equal to three ounces.

The cubit, one the earliest forms of measurement known, was the distance between a person's elbow and fingertip — roughly 18 inches. The symbol for a cubit, a forearm, appeared on Egyptian papyrus texts thousands of years old. King Menes decreed a sacred or royal cubit 14 percent larger than the common cubit. This measurement was used to build his houses but was forbidden for others to use.

A cubit was the unit of measure throughout much of the ancient world. The measurement varied a great deal however. In ancient Egypt, for example, a cubit for a man was 17.72 inches while the cubit for a king was 20.62 inches. Both the Great Pyramids of Cheops and Noah's Ark were built to cubits. The latter was 300 cubits long.

Ancient Egyptian Calendar

Although Mesopotamians devised the first calenders the Egyptians conceived the modern 365-day, 12 month calendar. Egyptians added five days to the Babylonian 360-day calendar. The ancient Egyptian civil calendar had three season: 1) Akhet (Flooding); 2) Peret (Growing or Sowing); and 3) Shemu (Harvest). Each season had four months with 30 days. The additional five days were tacked onto the end of Harvest and set aside for feasting during the annual flooding of the Nile. The Hindus and Chinese also used 365-day calendars.

The Babylonians are often given credit for devising the first calendars, and with them the first conception of time an entity. They developed the used the 360-day year — divided into 12 lunar months of 30 days (real lunar months are 29½ days) — devised by the Sumerians and introduced the seven day week, corresponding to the four waning and waxing periods of the lunar cycle. The ancients Egyptians adopted the 12-month system to their calendar. The ancient Hindus, Chinese, and Egyptians, all used 365-day calendars.

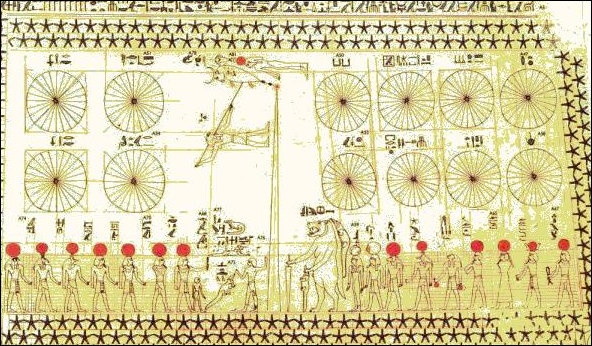

Calendar of Senenmut-Grab

Egypt devised a 365-day calendar as early as the 5th millennium based on flood of the Nile which occurred at almost the same time every year. The Egyptian year began in July when the Nile usually flooded and was marked by the rising of the star Sirius in the eastern horizon just before daybreak.

The Egyptians discovered that not only did the star Sirius line up with the rising sun around the time of flooding every year they also noticed that Sirius lined up with sun about six hours (a ¼ a day) different every year. They were among the first people to realize the need for a leap day. For a while they inserted a leap day into their calendar but then abandoned it. This meant their calendar would slip a day every four years and an entire month every 120 years. A trilingual description of changes to be made to the Egyptian calendar was found at the temple of Bubastis, the 8th century capital of Egypt. The 2,200-year-old stellate described planned changes for the Egyptian calendar that were implemented d250 years later by Julius Caesar.

See Separate Article: CALENDARS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Astronomy

The Egyptians of the New Kingdom, if not those of earlier date, possessed the elements of real astronomy. On the one hand they tried to find their way in the vastness of the heavens by making charts of the constellations according to their fancy, charts which of course could only represent a small portion of the sky. On the other hand they went further, they made tables in which the position of the stars was indicated. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Sara Moldaschel of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “The Ancient Egyptians had a limited knowledge of astronomy. Part of the reason for this is that their geometry was limited, and did not allow for complicated mathematical computations. Evidence of Ancient Egyptian disinterest in astronomy is also evident in the number of constellations recognized by Ancient Egyptians. At 1100 B.C., Amenhope created a catalogue of the universe in which only five constellations are recognized. They also listed 36 groups of stars called decans. These decans allowed them to tell time at night because the decans will rise 40 minutes later each night. Theoretically, there were 18 decans, however, due to dusk and twilight only twelve were taken into account when reckoning time at night. Since winter is longer than summer the first and last decans were assigned longer hours. Tables to help make these computations have been found on the inside of coffin lids. The columns in the tables cover a year at ten day intervals. The decans are placed in the order in which they arise and in the next column, the second decan becomes the first and so on. [Sources: Sara Moldaschel Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, “The Cambridge Illustrated History of Astronomy.” Michael Hoskin, ed. Cambridge University Press,1997; Springer-Verlag and Hugh, Thurston. “Early Astronomy,” New York, Inc. 1994]

“Astronomy was also used in positioning the pyramids. They are aligned very accurately, the eastern and western sides run almost due north and the southern and northern sides run almost due west. The pyramids were probably originally aligned by finding north or south, and then using the midpoint as east or west. This is because it is possible to find north and south by watching stars rise and set. However, the possible processes are all long and complicated. So after north and south were found, the Egyptians could look for a star that rose either due East or due West and then use that as a starting point rather than the North South starting point. This would result in the pyramids being more accurately aligned with the East and West, which they are, and all of the errors in alignment would run clockwise, which they do. This is because of precession of the poles which is very difficult to view, and the Ancient Egyptians did not know about. This theory is further substantiated by the fact that the star B Scorpii’s rising-directions match with the alignment of the pyramids on the dates at which they were built. +\

See Separate Article: ASTRONOMY IN ANCIENT EGYPT: STARS, TABLES, OBSERVATORY africame.factsanddetails.com

sundial

Inventions by Ancient Egyptians

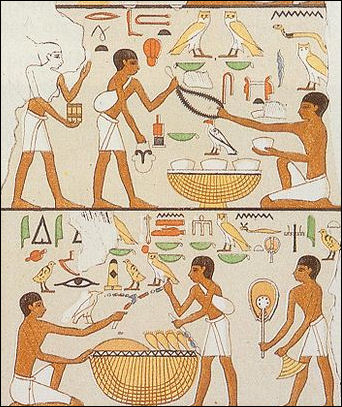

The Egyptians are credited with inventing writing, mathematics, geometry, surveying, metallurgy, astronomy, accounting, writing materials, medicine, the ramp, the lever, the plough, and mills for grinding grain. Whether they unilaterally were the first to devise these advancements is a matter of considerable debate but least they contributed greatly to their inception and widespread use. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Agriculture advancements credited to the ancient Egyptians include 1) the ox-drawn plough, 2) irrigation, 3) the sickle, a curved blade used for cutting and harvesting grain, and the shadoof, a long balancing pole with a weight on one end and a bucket on the other. The ox-drawn plough — - a plough pulled by oxten — revolutionized agriculture. Modern versions of the plough are still widely used today Egyptian irrigation consisted of canals and irrigation ditches primarily used to harness Nile river’s yearly flood and bring water to distant fields. The shadoof’s bucket could easily be filled with water and raised to bring water to higher ground. ^^^

The ancient Egyptians are also credited with toothpaste. Mark Millmore of discoveringegypt.com wrote: “At the 2003 dental conference in Vienna, dentists sampled a replication of ancient Egyptian toothpaste. Its ingredients included powdered of ox hooves, ashes, burnt eggshells and pumice. Another toothpaste recipe and a how-to-brush guide was written on a papyrus from the fourth century AD describes how to mix precise amounts of rock salt, mint, dried iris flower and grains of pepper, to form a “powder for white and perfect teeth.”“ [Source:Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Clocks and Sundials in Ancient Egypt

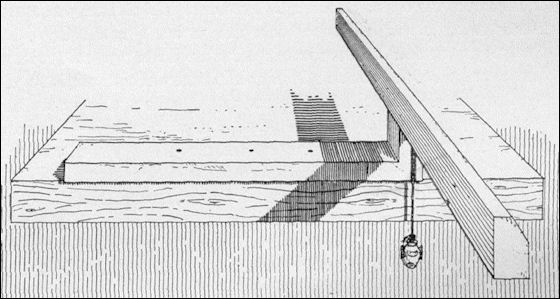

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “In order to tell the time Egyptians invented two types of clock. Obelisks were used as sun clocks by noting how its shadow moved around its surface throughout the day. From the use of obelisks they identified the longest and shortest days of the year. An inscription in the tomb of the court official Amenemhet dating to the16th century B.C. shows a water clock made from a stone vessel with a tiny hole at the bottom which allowed water to dripped at a constant rate. The passage of hours could be measured from marks spaced at different levels. The priest at Karnak temple used a similar instrument at night to determine the correct hour to perform religious rites. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

sundial Sarah Symons of McMaster University has pointed out that the idea that obelisks at temples as were used as sundials is probably untrue. Yes, there was connection between the obelisks and with the sun: the high point of an obelisk, covered with an alloy of gold and silver, reflected the sun before sunrise. The main function of obelisks, according to obelisk engravings, was to serve honor the pharaoh that commissioned it. Only when obelisks were taken from Egypt and placed in Rome and Paris were they used as a sundials.

The ancient Egyptians are thought to have been the first people to develop sun dials although there are some claims the Chinese developed them around the same time. The oldest Egyptian sun dials have been dated at 3500 B.C. A fragment of one at Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has been dated to about 3000 B.C. The largest surviving sundial is the 31-meter-high obelisk of Karnak, erected around 1470 B.C. It casts its shadow on a temple of the sun god Amun Ra.

A portable Egyptian sundial, or “shadow clock,” that survives from the time of Thutmose III (c. 1500 B.C.) is a horizontal bar about a foot long with a T-shaped structure at one end that casts a shadow on marks on the horizontal bar. In the morning the bar was set with the T facing east; at noon the T was revered and faced west. An example from the 8th century B.C. can be found at the Museum of the Ancient Agora in Athens.

See Separate Article: CLOCKS AND SUN DIALS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

First Wheels, Wheeled Vehicles and Horses

The wheel, some scholars have theorized, was first used to make pottery and then was adapted for wagons and chariots. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in 4000 B.C. Some scholars have speculated that the wheel on carts were developed by placing a potters wheel on its side. Other say: first there were sleds, then rollers and finally wheels. Logs and other rollers were widely used in the ancient world to move heavy objects. It is believed that 6000-year-old megaliths that weighed many tons were moved by placing them on smooth logs and pulling them by teams of laborers.

Ancient Egyptian cart

Early wheeled vehicles were wagons and sleds with a wheel attached to each side. The wheel was most likely invented before around 3000 B.C.”the approximate age of the oldest wheel specimens — as most early wheels were probably shaped from wood, which rots, and there isn't any evidence of them today. The evidence we do have consists of impressions left behind in ancient tombs, images on pottery and ancient models of wheeled carts fashioned from pottery.◂

Evidence of wheeled vehicles appears from the mid 4th millennium B.C., near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucasus and Central Europe. The question of who invented the first wheeled vehicles is far from resolved. The earliest well-dated depiction of a wheeled vehicle — a wagon with four wheels and two axles — is on the Bronocice pot, clay pot dated to between 3500 and 3350 B.C. excavated in a Funnelbeaker culture settlement in southern Poland. Some sources say the oldest images of the wheel originate from the Mesopotamian city of Ur A bas-relief from the Sumerian city of Ur — dated to 2500 B.C. — shows four onagers (donkeylike animals) pulling a cart for a king. and were supposed to date sometime from 4000 BC. [Partly from Wikipedia]

In 2003 — at a site in the Ljubljana marshes, Slovenia, 20 kilometers southeast of Ljubljana — Slovenian scientists claimed they found the world’s oldest wheel and axle. Dated with radiocarbon method by experts in Vienna to be between 5,100 and 5,350 years old the found in the remains of a pile-dwelling settlement, the wheel has a radius of 70 centimeters and is five centimeters thick. It is made of ash and oak. Surprisingly technologically advanced, it was made of two ashen panels of the same tree. The axle, whose age could not be precisely established, is about as old as the wheel. It is 120 centimeters long and made of oak. [Source: Slovenia News]

See Separate Article ANCIENT HORSEMEN AND THE FIRST WHEELS, CHARIOTS AND MOUNTED RIDERS factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Metallurgy

Early tools were made from copper and later bronze. Egyptian bronze tended to be around 88 percent copper and 12 percent tin. Iron was introduced by the Hittites in the 13th century but wasn't common until the 6th or 7th century B.C.

A wide variety of copper tools, fish hooks and needles were made. Chisels and knives lost their edge and shape quickly and had be reshaped with some regularity or simply thrown out. In the Old Kingdom (2700 to 2125 B.C.) there was only copper. Copper-making hearths have been found near the pyramids. Reliefs found nearby show Egyptians gathering around a fire smelting copper by blowing into long tubes with bulbous endings.

Knives tended be made from bronze. They were considerably sharper than copper knives. The sharpest knives of all were made of flaked obsidian. A wide variety of stone tools were also used, including pick axes and hammers.

Sculptures made of copper, bronze and other metals were cast using the lost wax method which worked as follows: 1) A form was made of wax molded around a pieces of clay. 2) The form was enclosed in a clay mold with pins used to stabilize the form. 3) The mold was fired in a kiln. The mold hardened into a ceramic and the wax burns and melted leaving behind a cavity in the shape of the original form. 4) Metal was poured into the cavity of the mold. The metal sculpture was removed by breaking the clay when it was sufficiently cool.

Egyptian alchemists thought that gold was a seed and the silver and copper were food that caused more gold to grow. One ancient Egyptian recipe for "diplosis" of gold called for two parts gold, one part copper and one part silver to be heated and mixed together. The result is twice as much gold (12 carat gold, when mixed the reddish tint of copper and the greenish tint of the silver doesn't change the color of the gold).

Mathematics in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians used a base-10 system of numbers. Sometimes they used different symbols for 1s, 10s, 100s, 1,000s, 10,000s, 100,000s and 1,000,000s. Other times they used a group of hieroglyphic symbols for individual numbers. Egyptian arithmetic was based on a system binary system like that used to power computers today. Multiplication was done by duplicating numbers and adding the sums together. Division was the same operation performed backwards.

Peter Schjeldahl wrote in The New Yorker: “The Egyptians were perniciosus keepers of lists, and recorders of methods and procedures. They meant for things they made to last forever.”To rule effectively, the ancient Egyptians set up an efficient and extensive administration that levied taxes, conducted censuses, and maintained and supplied a large army — all of which required some mathematics. At first they used counting glyphs. By 2000 B.C., hieratic glyphs were in use.

Herodotus wrote: Ramses II “divided the land into lots and gave a square piece of equal size, from the produce of which he exacted an annual tax. [If] any man's holding was damaged by the encroachment of the river ... [The Pharoah] ... would send inspectors [and surveyors] to measure the extent of the loss, in order that he pay in future a fair proportion of the tax at which his property had been assessed. Perhaps this was the way in which geometry was invented, and passed afterwards in to Greece.

See Separate Article: MATHEMATICS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024