INDUSTRIES IN ANCIENT EGYPT

brick making

Pottery making was well advanced by 3000 B.C. The earliest Egyptian pottery was unglazed red earthenware. Both Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt had the pottery wheel by that time. The potter's wheel is believed to have been invented in Mesopotamia around 3500 B.C. and may be tied to the invention of wheeled vehicles. See Mesopotamia.

The Egyptians developed fairly sophisticated chemistry through cosmetic-making, dying, glassmaking and gold and iron metallurgy. Glassmaking was known in ancient Egypt as far back as 2500 B.C. The bottle was invented sometime around 1500 B.C. by Egyptian artisans. Glass from Egypt

A wide variety of copper tools, fish hooks and needles were made. Chisels and knives lost their edge and shape quickly and had be reshaped with some regularity or simply thrown out. In the Old Kingdom (2700 to 2125 B.C.) there was only copper. Copper-making hearths have been found near the pyramids. Reliefs found nearby show Egyptians gathering around a fire smelting copper by blowing into long tubes with bulbous endings.

Sculptures made of copper, bronze and other metals were cast using the lost wax method which worked as follows: 1) A form was made of wax molded around a pieces of clay. 2) The form was enclosed in a clay mold with pins used to stabilize the form. 3) The mold was fired in a kiln. The mold hardened into a ceramic and the wax burns and melted leaving behind a cavity in the shape of the original form. 4) Metal was poured into the cavity of the mold. The metal sculpture was removed by breaking the clay when it was sufficiently cool.

In 2019, Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities unveiled the discovery of an ancient industrial zone in Luxor’s West Valley, also known as the Valley of the Monkeys. Reuters reported: Egyptian archaeologists discovered 30 workshops in the industrial area "composed of houses for storage and the cleaning of the funerary furniture with many potteries dated to Dynasty 18," the excavation team's leader, Zahi Hawass, said in the statement. “The manufacturing area contains a deep cut and a water storage tank that had been used by workers, the statement said. Between them the archaeologists have found a scarab ring, hundreds of inlay beads and golden objects that were used to decorate royal coffins and some inlays known as the wings of Horus. [Source: Reuters, October 11, 2019]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries” by A. Lucas and J. Harris (2011) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Towns and Cities” by Eric Uphill (2008) Amazon.com;

“'Make it According to Plan': Workshop Scenes in Egyptian Tombs of the Old Kingdom” by Michelle Hampson (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation” by Ian Shaw (2012)

Amazon.com;

”The Production, Use and Importance of Flint Tools in the Archaic Period and the Old Kingdom in Egypt” by Michał Kobusiewicz (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Origins and Use of the Potter’s Wheel in Ancient Egypt” by Sarah Doherty (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Metallurgy” by H. Garland and C. O. Bannister (2015) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Metalworking and Tools” by Bernd Scheel (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Competition of Fibres: Early Textile Production in Western Asia, Southeast and Central Europe (10,000–500 BC)” by Dr. Wolfram Schier and Prof. Dr Susan Pollock (2020) Amazon.com;

“Tools, Textiles and Contexts: Investigating Textile Production in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age” by Eva Andersson Strand and Marie-Louise Nosch (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Textiles: Production, Crafts and Society” by Marie-Louise Nosch, C. Gillis (2007) Amazon.com;

“First Textiles: The Beginnings of Textile Production in Europe and the Mediterranean” by Małgorzata Siennicka, Lorenz Rahmstorf, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Commerce and Economy in Ancient Egypt” by Andras Hudecz (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Economy: 3000–30 BCE” by Brian Muhs (2018) Amazon.com;

Urban-Village Manufacturing Centers in Amarna

On archaeological finds in Amarna, Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “Like most settlement sites, industry leaves a particularly strong signature in the archaeological record of Amarna in the form of manufacturing installations, tools, and by-products. The site has contributed significantly to the study of the technological and social aspects of such industries as glassmaking, faience production, metalwork, pottery production, textile manufacture, basketry, and bread-making, and has been one of the hubs of experimental archaeology in Egypt.” Most of the places can be classified as “small-scale domestic production, courtyard establishments or formal institutional workshops” [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

bakery

Marsha Hill of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Village-like complexes produced statuary; stone, faience, and glass vessels, jewelry, or inlays; metal items, and the like. Usually several industries operated in the same complex, serving the furnishing and embellishment of the royal buildings and other needs; by providing for these workers, the official heading the complex must have had rights to the things produced, which he then provided toward the court undertakings. By contrast, a gridded, officially planned settlement, created probably to house workers on the royal tombs and known as the Workman's Village, lay out in the desert plain between the city and the eastern cliffs. Houses themselves, from the simplest to the most elaborate, favored a plan with an oblique entry, a central room with a low hearth for reception or gathering, pillared when possible, and bedrooms and workrooms further back. Second stories may have existed, but sleeping might also take place on the roof. Cooking and food preparation seem to have been done in courtyards. [Source: Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 2014, metmuseum.org \^/]

“As a beehive of building and production, the city provides many insights into ancient industry and technology, from construction, to manufacture of glass and faience, to statuary and textile production, to bread making. One revelation is the ubiquity of gypsum as a working material. Gypsum can be used as a stone, but its main use at Amarna was as a powdered material, which with various admixtures can produce anything from a hardening plaster, to an adhesive, to a concrete. Gypsum had long been employed in Egypt as a mortar, a ground for painting, and for its adhesive qualities, but at Amarna it was used to create great long foundation levels, to build up platforms, and in a few instances to form large concrete blocks that functioned like stone. It was used as a mortar for talatat and glue for inlay. It may even have been used to create a whole large stela surface in the newly discovered boundary stela H. And it was used to adhere the elements of the composite statuary created at Amarna, and apparently to construct some balustrades from a three-dimensional mosaic of pieces. The combination of flourishing and inventive composite methods with the ubiquitous use of gypsum-based adherents has the appearance of an acceleration of technological change that constitutes a kind of breakthrough, whether or not it had any validity when Amarna and Amarna systems were abandoned. \^/

Ancient Egyptian Pottery and Ceramics

Pottery making was well advanced by 3000 B.C. The earliest Egyptian pottery was unglazed red earthenware. Both Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt had the pottery wheel by that time. The potter’s wheel is believed to have been invented in Mesopotamia around 3500 B.C. and may be tied to the invention of wheeled vehicles. See Mesopotamia.

The Egyptians developed fairly sophisticated chemistry through cosmetic-making, dying, glassmaking and gold and iron metallurgy. Ceramic objects could be decorative, used in daily life or have religious significance. Bottles, jars and jugs used to carrying things and for storage were often made of fired clay. Decorative pottery was sometimes covered with a blue glaze. Many types of ornamental pottery were made for royalty and aristocrats. Even beads and jewelry were made of clay.

Paul T. Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “Pottery is usually the most common artifact on any post- Mesolithic site. In Egypt its abundance can fairly be described as overwhelming, and it generally requires substantial resources in order to be properly recorded by excavators. Pottery was the near- universal container of the ancient world and served those purposes for which we might now use plastics, metal, glass and, of course, modern ceramics. Its abundance in the archaeological record is not due merely to its wide use, but to its near indestructibility, and this is in turn a facet of its technology. [Source: Paul T. Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN POTTERY AND CERAMICS africame.factsanddetails.com

Papyrus Making

Sheets of papyrus were made by gluing the mats together. Scrolls were made my gluing sheets together. When dried out papyrus naturally curled up which is why most ancient literary works were in the form of scrolls. Scrolls were fairly durable but frequent rolling and unrolling caused the written words to wear off.

papyrus splitting

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Papyrus making was not revived until around 1969. An Egyptian scientist named Dr. Hassan Ragab reintroduced the papyrus plant to Egypt and started a papyrus plantation near Cairo. He also had to research the method of production. Because the exact methods for making papyrus paper was such a secret, the ancient Egyptians left no written records as to the manufacturing process. Dr. Ragab finally figured out how it was done, and now papyrus making is back in Egypt after a very long absence. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“The Method of Papyrus Paper Production: 1) The stalks of the papyrus plant are harvested. 2) Next the green skin of the stalk is removed and the inner pith is taken out and cut into long strips. The strips are then pounded and soaked in water for 3 days until pliable. 3) The strips are then cut to the length desired and laid horizontally on a cotton sheet overlapping about 1 millimeter. Other strips are laid vertically over the horizontal strips resulting in the criss-cross pattern in papyrus paper. Another cotton sheet is placed on top. 4) The sheet is put in a press and squeezed together, with the cotton sheets being replaced until all the moisture is removed. 5) Finally, all the strips are pressed together forming a single sheet of papyrus paper.” +\

See Separate Article: PAPYRUS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MAKING IT AND THE WORLD'S OLDEST PAPYRI AND BOOK africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Glass Factory

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “In Egypt and the rest of the Middle East in the 13th century B.C., bronze was the heavy metal of power, and glass the rare commodity coveted by the powerful, who treasured glass jewelry, figurines and decorative vessels and exchanged them as prestige gifts on a par with semiprecious stones. But definitive evidence of the earliest glass production long eluded archaeologists. They had found scatterings of glassware throughout the Middle East as early as the 16th century B.C. and workshops where artisans fashioned glass into finished objects, but they had never found an ancient factory where they were convinced glass had been made from its raw materials. [Source:John Noble Wilford, New York Times, June 21, 2005 **]

"In 2005 two archaeologists reported finding such a factory in the ruins of an Egyptian industrial complex from the time of Rameses the Great. The well-known site, Qantir-Piramesses, in the eastern Nile delta, flourished in the 13th century B.C. as a northern capital of the pharaohs. Dr. Thilo Rehren of the Institute of Archaeology at University College London told the New York Times, "This is the first ever direct evidence for any glassmaking in the entire Late Bronze Age." **

"Other experts familiar with the research said the findings were important for reconstructing the ancient technology of glassmaking. But some questioned the claim that Qantir represented the first evidence of primary glass production, citing previous findings in Egypt at Amarna, which are dated a century earlier. Dr. Rehren and Dr. Edgar B. Pusch of the Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim, Germany, said they had excavated cylindrical crucibles and remains of glass raw materials in various stages of production. The site yielded samples of quartz grains, thought to be the main silica source of glassmaking in the Bronze Age. **

metal workers

See Separate Article: GLASS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, PRODUCTION, HOT AND COLD WORKING africame.factsanddetails.com

Woodworking in Ancient Egypt

Egyptian carpenters made boats, carriages, portions of houses, furniture, the weapons, coffins, and various kinds of grave goods. When native woods were used, we find a complete lack of planks of any great length; instead objects were made by putting together small planks to form one large one. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Wooden furniture, was generally painted; there were other styles of decoration also in use, appropriate to the character of the material in question. Thin pieces of wood, such as were joined together for light seats or were used for weapons, were left with their bark on; they were also sometimes surrounded with thin strips of barks of other colors — a system of ornamentation which has still a very pleasing effect from the shining dark colors of the various barks. A second method was more artistic; a pattern was cut deeply into the wood and then inlaid with wood of another color, with ivory, or with some colored substance. The Egyptians were especially fond of inlaying “ebony with ivory. " This inlaid work is mentioned as early as the Middle Kingdom, and examples belonging to that period also exist. In smaller objects of brown wood, on the other hand, they filled up the carving with a dark green paste.

The Berlin coffins of the time of the Middle Kingdom are excellent ancient specimens of these various styles of workmanship. Images of coffin making show workman bringing strips of linen for cartonage, polishing and painting the coffins, boring holes in the wooden footboards, sawing planks. They also show a leg of a stool cut with an adze. Behind lies the food for the men, close to which a tired-out workman has seated himself.

See Separate Article: FURNITURE AND WOODWORKING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Stone Tools Manufacturing in Ancient Egypt

making flint knives

André Dollinger wrote in his Pharaonic Egypt site: “The amount of work a knapper invested in making a tool was dependent on the length of time it could be expected to be used. Axes which received harsh treatment and therefore broke quickly were generally fashioned with a few well-placed strokes. The heads were fastened to the handles by cutting a socket into the wood, inserting the blade and tying it with a cord two or three feet in length. No cement was used.

“Broken tools were often reshaped and dull edges resharpened. Axe heads were sometimes ground down to such an extent that little stone was left protruding from the socket, before they were discarded. Knapping was quite a difficult craft and became specialised in pre-historic times. Workshops producing stone tools have been found in 4th millennium Hierakonpolis.

“The advancing bronze age saw a decline in the frequency of use and quality of stone tools, not just because metal displaced stone but possibly also because the best craftsmen preferred the material which offered the more interesting possibilities. Bronze tools must have been significantly more expensive than flint and therefore less affordable. Knapping, a specialized profession once, probably became one of the tasks which labourers who were not very expert at it but too poor to be able to purchase metal tools, had to perform of necessity. The quality of the stone had deteriorated as well. Deposits closer-by were being exploited despite the poor quality of the flint. But the knowledge of manufacturing basic stone blades continued until Roman times.

See Separate Article: TOOL MANUFACTURING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Leatherworking in Ancient Egypt

André J. Veldmeijer of the Netherlands Flemish Institute in Cairo wrote: “Leather was used throughout Egypt’s history, although its importance varied. It had many applications, ranging from the functional (footwear and wrist-protectors, for example) to the decorative (such as chariot leather). Although leather items were manufactured using simple technology, leatherworking reached a high level of craftsmanship in the New Kingdom. Among the most important leather-decoration techniques employed in Pharaonic Egypt, and one especially favored for chariot leather, was the use of strips of leather of various colors sewn together in partial overlap. In post-Pharaonic times there was a distinct increase in the variety of leather-decoration techniques. Vegetable tanning was most likely introduced by the Romans; the Egyptians employed other methods of making skin durable, such as oil curing.” [Source: André J. Veldmeijer, Netherlands Flemish Institute Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

cabinet making

“The term “leather” refers to skins that have been tanned or tawed—that is, converted into white leather by mineral tanning, as with alum and salt—rather than cured. In Egypt it appears that skins were not tanned or tawed in the Pharaonic Period; however, thus far we lack detailed, systematic chemical analyses from which to make a conclusive determination. Skins and leather were used throughout Egyptian history, but their importance and quality varied. According to Van Driel- Murray, skins were widely used in the Badarian and Amratian (Naqada I) periods but were largely superseded by cloth in the Gerzean (Naqada II).

“In Egypt leather was most commonly made from the skins of cow, sheep, goat, and gazelle, although those of more exotic species such as lion, panther, cheetah, antelope, leopard, camel, hippopotamus, crocodile, and possibly elephant have been identified. Leather was used in a wide variety of items, ranging from clothing, footwear, and cordage, to furniture and (parts of) musical instruments.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN SHOES, HATS AND LEATHERWORKING africame.factsanddetails.com

Weaving in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians were skilled weavers. Many inscriptions extol the garments of the gods and the bandages for the dead. The preparation of clothes was considered as a rule to be woman's work, for truly the great goddesses Isis and Ncphthys had spun, woven, and bleached clothes for their brother and husband Osiris. During the Old Kingdom this work fell to the household slaves, in later times to the wives of the peasant serfs belonging to the great departments. In both cases it was the house of silver to which the finished work had to be delivered, and a picture of the time of the Old Kingdom shows us the treasury officials packing the linen in low wooden boxes, which are long enough for the pieces not to be folded. Each box contains but one sort of woven material, and is provided below with poles on which it is carried by two masters of the treasury into the house of silver. In other cases we find, as Herodotus wonderingly describes, men working at the loom; and indeed on the funerary stelae of the 20th dynasty at Abydos, we twice meet with men who call themselves weavers and follow this calling as their profession. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

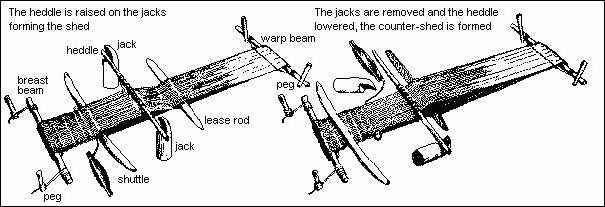

The operation of weaving was a very simple one during the Middle Kingdom. The warp of the texture was stretched horizontally between the two beams, which were fastened to pegs on the floor, so that the weaver had to squat on the ground. Two bars pushed in between the threads of the warp served to keep them apart; the woof-thread was passed through and pressed down firmly by means of a bent piece of wood. " A picture of the time of the New Kingdom however gives an upright loom with a perpendicular frame. The lower beam appears to be fastened, but the upper one hangs only by a loop, in order to facilitate the stretching of the warp. We also see little rods which are used to separate the threads of the warp; one of these [ certainly serves for a shuttle. A larger rod that runs through loops along the side beams of the frame appears to serve to fix the woof-thread, like the reed of our looms.

See Separate Article: WEAVING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Egyptian-era loom

Cordage Production in Ancient Egypt

André J. Veldmeijer of the Netherlands Flemish Institute in Cairo wrote: “The term “cordage” refers to rope and string, and to the products made from these, such as netting. Its presence among some of the oldest artifacts found on archaeological sites testifies to its usefulness through the ages. In ancient Egypt, the production of cordage was relatively simple, for it could be made by hand without special implements. However, the manufacture of thick rope required the efforts of more than one person and/or the use of special tools. Various materials were used to make cordage, depending on the availability of the necessary plants and also on the intended function of the cordage. [Source: André J. Veldmeijer, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“The term “cordage” refers to rope and string, and to the products made from these, such as netting. Cordage, basketry, and textiles are closely related. Indeed some objects can be regarded as both basketry and cordage. For example, bed matting is made of spun or plied strings (“linear cordage”) that are woven, weaving being considered a basketry technique. In the present discussion, focusing on the cordage of ancient Egypt, the relevant terms have been defined in such a way as to avoid overlapping as much as possible. Definitions and terminology follow those presented in the author’s work. The terms “twist” and “composition” can, accordingly, be explained as follows: The “twist” is the orientation of yarns, plies, and cables, visualized by reference to the letters ‘z’ or ‘s’ (yarns), ‘Z’ or ‘S’ (plies), ‘[Z]’ or ‘[S]’ (cable), ‘{Z}’ or ‘{S}’ (double cable). The central stroke of the letter marks the orientation of the twist. “Composition” refers to the orientation and number of the subsequent levels of the piece. A number following the ‘Z’ or ‘S’ shows the number of yarns or plies used. For instance, zS2[Z3] means that two z- twisted yarns (2) are plied in the S-direction. Then three (3) of these plies are cabled in the [Z]-direction. The composition of non-plied cordage (yarns) cannot be visualized because yarns are the first level of production. Therefore, when yarns are referred to, only the twist is mentioned.

Two or three phases in the production of cordage can be identified, depending on whether the end product was linear cordage or an object made from linear cordage, such as netting. These phases are depicted in varying degrees of detail in several tombs. First, before cordage could be made, the required plants had to be grown and their usable components harvested. The plants most commonly used for making cordage constitute the primary focus here— namely halfa grasses, reeds, and palm—as opposed to sedges, cotton, and rawhide/leather. Papyrus, a sedge, seems to have been used mostly for the manufacture of thick rope, although thick ropes found in caves at the ancient port of Mersa/Wadi Gawasis were made not of papyrus but reed. Fine string made from the epiderm of the papyrus culm has occasionally been found at Pharaonic-Period sites, as represented by an amphora sling from Amarna, for example. The epiderm may have been a by-product of papyrus production. Some cultivated plants, such as flax, were employed, but others grew wild and needed only to be harvested, grass being an example.

“The preparation of plants for rendering into cordage depended on the material: grass required more preparation than palm, the procedure involving, according to Greiss, soaking and beating. Ethno- archaeological observations made by Wendrich, however, differ in that grass was dried for three to five days and wetted just before use. The preparation of date-palm leaves, according to Wendrich, involved thorough drying before the side leaflets were removed; the leaf-sheath fiber could be used after soaking briefly. Dom palm leaves were dried for a minimum of two weeks, after which the leaves were split. The preparation of flax for textile production was much more elaborate and involved various stages, including retting and beating, or bruising. It is noteworthy that this process might have been less intense had its purpose been the manufacture of cordage, as many archaeological examples prove. Less commonly used in cordage manufacture were animal products, namely goat hair, which may have involved washing before spinning and plying.

“The second phase comprised the production of linear cordage. Short lengths of grass or palm linear cordage could easily be made by rolling two bundles between the hands. Wendrich describes in detail how a string with alternating twist is made in two simple movements. It is noteworthy that the composition of string varied widely; string featuring alternating twists prevails (the alternating direction of the spinning and plying strengthens the piece, making it less prone to falling apart), although non- alternating twists do occur. The strength of the spinning and plying influences the strength of the cordage and is itself dependent on various factors, among which is the material. The production of longer and thicker pieces of linear cordage, such as those discovered at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis, involved various persons, as can be seen in tomb representations, and may therefore have been a (semi-) specialized craft. Depicted in the tomb of Khaemwaset, for example, is a scene in which a person twists fibers into a yarn by means of a tool with a weight. A second person plies two pieces of yarn, while a (third) person in the center regulates the tension of the plying. Texts mention ropes as long as 1000 cubits, the rough equivalent of 500 meters. In the later New Kingdom we know that the price of rope was about 1 deben of silver—that is, the worth of about 2 cattle—for 100 cubits.

rope making

“The spinning of flax thread for the production of textiles is well known and described in detail by various authors. Vogelsang-Eastwood suggests that first the flax fibers were loosely twisted and then spun into the final thread in a second stage. Usually, flax fibers were wetted before being spun, after which the thread could be plied, used in the manufacture of textiles, or, less commonly, made into a net, most of the flax netting having been made of plied string. A third phase of manufacture can be identified if the linear cordage was used to render an object.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024