LABOR IN ANCIENT EGYPT

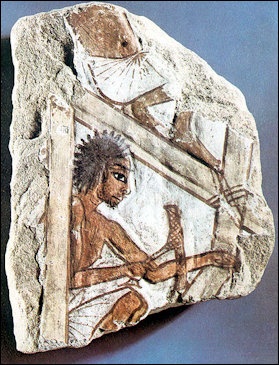

Egyptian carpenter

As agriculture became more advanced, surpluses were generated, freeing farmers to perform other jobs. Over time former farmers could earn enough to specialize in certain tasks and become what would qualify as craftsmen.

Organized labor was also needed to build other structures, quarry stone, mine precious metals and stones and build and maintain irrigation canals and other water projects. The Egyptians built many canals and irrigations systems. They didn’t make so many roads. Roads were not so important because they relied on the Nile for transportation. The Egyptian economy in the time of the pyramids was powered the by the construction of the pyramids. Pyramids building required labor. An economy was necessary to pay them.

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “The principal production and revenues of Egyptian society as a whole and of its individual members was agrarian, and as such, dependent on the yearly rising and receding of the Nile. Most agricultural producers were probably self-sufficient tenant farmers who worked the fields owned by wealthy individuals or state and temple estates. In addition to these, there were institutional and corvée workforces, and slaves, but the relative importance of these groups for society as a whole is difficult to assess. According to textual evidence, crafts were in the hands of institutional workforces, but indications also exist of craftsmen working for private contractors.[Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Labor in the Ancient World” by Michael Hudson and Piotr Steinkeller (2015) Amazon.com;

“'Make it According to Plan': Workshop Scenes in Egyptian Tombs of the Old Kingdom” by Michelle Hampson (2022) Amazon.com;

“Labour Organisation in Middle Kingdom Egypt, Illustrated, by Micòl Di Teodoro (2018) Amazon.com;

”The Production, Use and Importance of Flint Tools in the Archaic Period and the Old Kingdom in Egypt” by Michał Kobusiewicz (2016) Amazon.com;

“Stone Tools in the Ancient Near East and Egypt: Ground Stone Tools, Rock-cut Installations and Stone Vessels from Prehistory to Late Antiquity” by Andrea Squitieri and David Eitam (2019) Amazon.com;

“Slavery and Dependence in Ancient Egypt: Sources in Translation

by Jane L. Rowlandson , Roger S. Bagnall, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia” by Jacqueline Dembar Greene (2000), For Older Kids, Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Society” by Danielle Candelora, Nadia Ben-Marzouk, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in Babylonia: From Nabopolassar to Alexander the Great 626-331 BC”

by Muhammad A. Dandamaev , Victoria A. Powell, et al. (1984) Amazon.com;

“Did the Old Testament Endorse Slavery?” by Joshua Bowen 2023 Amazon.com;

“The Creation of Inequality: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire” by Joyce Marcus (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 1, The Ancient Mediterranean World”

Book 1 of 4: by Keith Bradley and Paul Cartledge (2011) Amazon.com;

Work in Ancient Egypt

As agriculture became more advanced, surpluses were generated, freeing farmers to perform other jobs. Over time former farmers could earn enough to specialize in certain tasks and become what would qualify as craftsmen. Organized labor was also needed to build other structures, quarry stone, mine precious metals and stones and build and maintain irrigation canals and other water projects. The Egyptians built many canals and irrigations systems. They didn't make so many roads. Roads were not so important because they relied on the Nile for transportation. The Egyptian economy in the time of the pyramids was powered the by the construction of the pyramids. Pyramids building required labor. An economy was necessary to pay them.

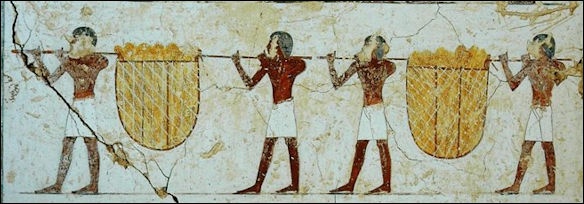

grinding grain

For much of the year it seems that most people in ancient Egypt were involved in agricultural activity of some kind, but during the flood (July-October) the workforce was used by the state to do things like build pyramids and monuments or engage in major projects such as "rehabilitation" of the land following the recession of the flood. This involved re-establishing property boundaries and maintaining the irrigation system through work such recutting canals and rebuilding dykes.” [Source: ABZU, University of Chicago Oriental Institute, oi-archive.uchicago.edu ]

According to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: “During and after the annual flood of the Nile, the population were subject to compulsory labour on state projects such as building and maintenance of the irrigation system. In life it would be possible to avoid this by providing a substitute; in death, mummiform figurines or "Answerers" could serve the same purpose. The Egyptian words for these statuettes (usually called shabtis in English), are ushabti and shawabti. These words are of uncertain origin but may have been derived from the Egyptian word wSb(1) meaning "answer." [Source: ABZU, University of Chicago Oriental Institute, oi-archive.uchicago.edu ]

In ancient Egypt there was paid labor (usually through rations), corvée compulsory labor and slavery. In addition there were farmers, at least some of whom were also workers during the season when there was not much agricultural work to do. Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “An income strategy different from subsistence was labor, either voluntary or compulsory. Compulsory labor is known from ancient Egypt in two forms: corvée and slavery. Corvée (bH) is well attested as periodical compulsory labor (especially in earlier periods), and everyone but the highest functionaries could be subjected to it. In the Old Kingdom, groups of workers subject to this practice were called mrt and worked in agricultural domains founded by the government . The same word mrt was used for the personnel of temple workshops in the New Kingdom; these were often prisoners taken during military campaigns. In the Middle Kingdom, temporary compulsory labor on state fields was controlled by the xnrt (interpreted as "labor camp" by Quirke). Even the nmH(y) of the New Kingdom (see Institutional and Private Interests above) could be summoned for service to government officials, as becomes clear from the decree of King Horemheb.” [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Activities and Occupations in Ancient Egyptian Villages

hunter

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “Leaving aside such “institutional” communities as Deir el-Medina or the pyramid towns, which relied directly on the Pharaonic administration, agriculture and herding were the main productive activities of Egyptian villages. It is probable that fishing and extensive herding led to the development of specific kinds of settlements and temporary encampments in particularly favored areas like the Fayum or the Delta. The 8th Dynasty inscription of Henqu of Deir el-Gabrawi, for instance, opposes two kinds of landscape, one formerly inhabited by fowlers, fishermen, and extensive herders, but subsequently settled by people and provided with flocks . The Gebelein papyri, from the end of the 4th Dynasty, contain a detailed list of the (presumable) heads of the households of several localities. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Many villagers were Hm nswt, “serf of the king,” or jst, “member of a team of workers,” and were probably peasants, but others were involved in activities such as herding, hunting, collecting honey, or fishing, and even some Hrj-Sa, “nomad”, are cited. Moreover, other people worked as millers and ship’s carpenters, whereas the scribes and agents of the crown must have formed the local elite alongside the chiefs of the villages. Thus, these documents provide an invaluable glimpse into the occupations and economic activities of some villages. Commercial activities are rarely documented, but marketplaces put the villagers in contact with other producers, traders, and institutions. Several New Kingdom papyri record ships in the service of temples, which collected goods from many localities, and some data suggest that private trade was also conducted during these journeys. It is possible that the growing importance of dmj(t) (“town, village,” but formerly “moorings, port”) in New Kingdom sources might be related to the growing importance of trade and river connections in the organization of the landscape. Finally, the tomb robbery papyri of the late New Kingdom reveal that private trade linked villagers and merchants, with precious metals fuelling non-institutional economic circuits where gold and silver were exchanged for plots of land, animals, and goods.

“Differences in wealth were obviously mirrored in the economy of villagers. Thus, for instance, yokes and ploughs, and probably donkeys too, were only accessible to rich peasants, whereas common villagers seem to have practiced intensive horticulture in small gardens. Archaeozoological research is providing increasing evidence of the importance of small-scale animal husbandry (pigs, sheep, and goats) in humble domestic contexts, and fish appears to have been an important component of poor people’s diets, sometimes imported from distant places thanks to private commercial circuits. Regional patterns of production and processing of food (i.e., barley at Abydos as opposed to emmer in Giza and Memphis), seasonal activities, the importance of fodder provision, the social patterns of differentiated consumption, etc. reveal a village economy less static and rather more complex than previously assumed, which was also subject to changes over time. Consequently, social hierarchy and wealth inequalities were reinforced by the risks inherent to agriculture as well as by indebtedness or heritage divisions, thus fostering clientelism and servitude and reinforcing the power of local leaders whose status was further enhanced by their connections with temples, regional potentates, and the agents of the crown.

Paid Labor Versus Corvee Labor in Ancient Egypt

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “Textual sources apparently concerned with wage labor actually refer to institutional workforces who were given rations. Rations could, however, could be so high as to enable the receiving institutional craftsmen to trade with their grain surplus. The same craftsmen could use their expertise to produce items for the market in their spare time in order to obtain additional income. There are no indications of the existence of a free labor market for craftsmen or other specialized workers. It is unlikely, however, that craftsmanship was only institutional: archaeological and ethnological research suggests industry, seasonal or permanent, in peasant households and local workshops.” [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “Little is known about the payment of urban workers, employed in either private or public constructions, in the form of wages rather than in the context of compulsory work (corvée labor). However, many inscriptions from the Old Kingdom do refer to officials who built their tombs with their own means and who remunerated the craftsmen and builders involved with copper and cloth, as well as grain and beer. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Thus, apparently, craftmen could be paid on a private basis and their skills put occasionally at the service of customers rather than institutional workshops. The huge New Kingdom construction projects at Pi-Ramesse, Karnak, and elsewhere, or the temples built in the first millennium BCE, likely mobilized a considerable combined mass of skilled workers, farmers engaged in unskilled work on a seasonal basis, craftspeople, and workers in charge of transport activities, etc., engaged on a “contractual” basis (not as corvée) and paid with wages (in some cases by private patrons).

“Indeed, demand for the latter individuals might have stimulated urban markets —for instance, the production of fresh vegetables in artificially irrigated gardens. In sharp contrast, the bulk of information at our disposal about people living in cities refers to scribes, administrators, priests, members of the court, military personnel, and agents of the crown.”

Corvee Labor in the Middle Kingdom

Sally Katary of Laurentian University wrote: “The collapse of the Old Kingdom was followed by the tumultuous First Intermediate Period during which the equilibrium between the central authority and powerful provincial interests broke down. The pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom were able to stabilize the central government. From the Middle Kingdom comes detailed documentation of punishments inflicted on peasants who sought to avoid the corvée and thereby deny the state its right to their occasional labor tilling fields, maintaining irrigation channels, working on construction projects, or obtaining raw materials abroad. [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University of Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446 describes the situation of eighty inhabitants of Upper Egypt who fled their national service obligations in the reign of Amenemhat III and were subsequently sentenced to indefinite terms of compulsory labor on government xbsw lands, their families imprisoned until their return. The agricultural labor referred to in this text is perhaps better described as conscription to forced tenancy on land undergoing development or redevelopment than what is commonly understood by the term “corvée labor”.

“Such conscription was a form of taxation by the state imposed upon all Egyptians below the rank of official, including priests and, most importantly, unskilled laborers from a huge labor pool at the bottom of Egyptian society, largely consisting of peasants tied to the land they worked, irrespective of its ownership. The burden of such forced agricultural labor for the vast majority of Egyptian laborers was not only inescapable but often unfairly and ruthlessly applied despite pleas to the authorities from persons unjustly seized. It is difficult to see how such persons would have benefited from a redistributive tax system, with the possible exception of those peasant farmers toiling upon the estates of temples exempted from the corvée by royal charter.

Apprenticeship in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “In contrast to “education,” whose conventional definition, in the case of this essay, covers aspects of basic training received at school, “apprenticeship” is a term that usually refers to a specific method of instruction, namely the instruction offered by a single teacher to a single or a small number of students on one or more specialized subjects or skills. This was a very popular educational method that was employed mainly when advanced training was sought out in order to develop some of the aspects of the curricula of Egyptian schools, such as writing or mathematics, or to introduce new subjects and skills, such as the study of religious texts or the learning of a craft. In addition, apprenticeship was a manner of instruction that was probably also used in some local Egyptian schools even for basic training— perhaps due to the small number of teachers and students available. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The term most probably denoting apprenticeship read Xrj-a, which literally meant “under the arm/control of,” while the expertteacher was called either nb, “master,” or jtj, “father.” The latter is a term employed mainly in literary contexts to imply a close father-son relationship for that between an instructor and his audience. Thus, for instance, the title “father” is often used in didactic texts, denoting the author of the instruction and teacher of an audience that has still much to learn: ‘Beginning of the sayings of excellent discourse spoken by the Prince….Ptahhotep, in instructing the ignorant to understand and be up to the standard of excellent discourse…So he spoke to his son.’ [Instruction of Ptahhotep]”

On the issue of sources regarding apprenticeships “in ancient Egypt, the available evidence concerns mainly the training of draftsmen and consists of: a) practice ostraca, and b) textual references to artisan training. As with school exercises, practice material can be identified as such due to their crude drawings and the fact that they were painted on ostraca...In contrast to the considerable amount of evidence available for basic school education in ancient Egypt, there is much less evidence for apprenticeship in advanced or special subjects and skills. Such evidence includes, for example, painted ostraca from Deir el-Medina that could have been made by artisan apprentices in situ. Probable references to such young apprentices are made in other ostraca from Deir el-Medina. Finally, there is also some evidence of the manner in which temple musicians were trained. Overall, the method of knowledge transfer through apprenticeship in Pharaonic Egypt was most likely informal and circumstantial, based not so much upon a uniform curriculum but rather upon the personal choices of the experienced professional who took over the education of his potential successors. The close relationship between artisan apprenticeship and school education is evident in the case of a number of tombs, in the context of which school exercises have been discovered. This evidence might indicate that Egyptian students were learning how to read and write by using the material inscribed on tomb walls. After all, tombs in ancient Egypt probably also functioned as places where important works of literature were meant to be preserved. In such cases, the artisan master who was overseeing the works in tombs would probably have also acted more broadly as a teacher.”

Was Child Labor Used to Build the Ancient Egyptian City of Amarna?

There is evidence that a ‘disposable’ workforce of children and teenagers provided much of the labor to build Amarna — the great capital city of Akhenaten (1353-1336 B.C.), the Pharaoh who tried to introduce monotheism to Egypt. Mary Shepperson wrote in The Guardian: “Amarna came and went in an archaeological moment. It rose and fell with Akhenaten and his religious reformation, under which Egypt’s ancient pantheon of gods was briefly usurped by the worship of a single solar deity; the Aten. Between 2006 and 2013 I was lucky enough to work for the Amarna Project on an excavation which aimed to recover four hundred individuals from a large cemetery behind the South Tombs cliffs, estimated to contain around six thousand badly looted burials. The study of these burials and their human remains has opened a new research window on life and death in the lower echelons of Egyptian society. They paint a picture of poverty, hard work, poor diet, ill-health, frequent injury and relatively early death. [Source:Mary Shepperson, University of Liverpool, The Guardian, June 6, 2017]

“In other respects the South Tombs Cemetery remains were fairly in line with expectations. There were modest variations in the wealth and style of burial, there was a fairly even mix of male to female individuals, and the age distribution showed the usual pattern for ancient populations; high infant mortality giving way to fewer deaths as children survive into early adulthood, with the death rate then rising again as adults succumb to illness, childbirth, injuries and age. This was all important and highly interesting, but not particularly unusual.

“In 2015 we began excavating another non-elite cemetery in a wadi behind a further set of courtiers’ tombs at the northern end of the city, and here the tale takes a stranger turn. As we started to get the first skeletons out of the ground it was immediately clear that the burials were even simpler than at the South Tombs Cemetery, with almost no grave goods provided for the dead and only rough matting used to wrap the bodies.

“As the season progressed, an even weirder trend started to become clear to the excavators. Almost all the skeletons we exhumed were immature; children, teenagers and young adults, but we weren’t really finding any infants or older adults. Our three excavation areas were far apart, spaced across the length of the cemetery, but comparing notes all three areas were giving the same result. This certainly was unusual and not a little bit creepy.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Did children build the ancient Egyptian city of Amarna? By Mary Shepperson, in The Guardian theguardian. com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024