HEALTH CARE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

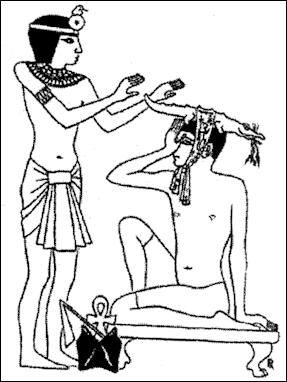

Migraine therapy

Egyptians used herbs and drugs as medicines and used splints to set broken bones. Anatomical knowledge appears to have been based more on animals than humans. Some surgery was done. Skulls with holes in them have been found.

In many ways, Egyptian medicine was advanced for its time. It existed long before the development of antibiotics or vaccines, but there is some evidence of public health measures such as the burning of towns and quarantining people. This suggests a basic understanding of how disease spreads. Diseases caused by microorganisms were viewed as supernatural, or as a corruption of the air — concepts that endured until germ theory was popularised in the 19th century. [Source Thomas Jeffries, Senior Lecturer in Microbiology, Western Sydney University, The Conversation, March 14, 2024]

Bodies were believed to have been cut open with obsidian blades. Bronze and copper knives were not sharp enough. In lieu of anesthesia patients were perhaps knocked on the head. The oldest set of bronze surgical blades dates to 2300 B.C. Medicines were made by a hierarchy of medicine makers that included a "chief preparer of drugs," "collectors of drugs," "preparers," "preparer's aides," and a “conservator of drugs" (in charge of storing drugs).

Dendara (near Qena, 40 kilometers north of Luxor) is the home of the Temple of Hathor, dedicated to the cow-headed goddess of healing. In ancient times, Dendara was associated with healing. Patients who traveled there for cures were housed in special buildings where they could rest, sleep, and commune with the gods in their dreams.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HEALTH OF ANCIENT EGYPTIANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE EXPECTANCY OF ANCIENT EGYPTIANS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN VIEWS ABOUT HEALTH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DISEASE IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MALARIA, CANCER, PLAGUES factsanddetails.com ;

HEALTH PROBLEMS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: INJURIES, ANEMIA, CLOGGED ARTERIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DOCTORS AND MEDICAL TREATMENT IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MEDICINES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Medicine of the Ancient Egyptians: 1: Surgery, Gynecology, Obstetrics, and Pediatrics” by Eugen Strouhal, Bretislav Vachala , et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Medicine of the Ancient Egyptians: 2: Internal Medicine” by Eugen Strouhal, Bretislav Vachala, Hana Vymazalová Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by John F. Nunn (2002) Amazon.com;

“Medicine and Healing Practices in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David and Roger Forshaw (2023) Amazon.com;

“An Ancient Egyptian Herbal” by Lise Manniche (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Papyrus Ebers: Ancient Egyptian Medicine” by Cyril P. Bryan (Translator) 2021) Amazon.com;

“The Edwin Smith Papyrus: Updated Translation of the Trauma Treatise and Modern Medical Commentaries” by Gonzalo M. Sanchez and Edmund S. Meltzer (2012) Amazon.com;

“Pharmacy and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Proceedings of the Conference Held in Barcelona (2018) by Rosa Dinares Sola, Mikel Fernandez Georges, Maria Rosa Guasch Jane Amazon.com;

“Health and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Magic and Science” by Paula Alexandra Da Silva Veiga (2009) Amazon.com;

“Healthmaking in Ancient Egypt: The Social Determinants of Health at Deir El-Medina

by Anne E. Austin (2024) Amazon.com;

“Science and Secrets of Early Medicine: Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, Mexico, Peru”

By Jurgen Thorwald (1963) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Medicine” (Sciences of Antiquity) by Vivian Nutton (2012) Amazon.com;

“Illness and Health Care in the Ancient Near East: The Role of the Temple in Greece, Mesopotamia, and Israel” (Harvard Semitic Monographs) by Hector Avalos (1995)

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Ancient Egyptian Understanding of the Body and Disease

Albert Zink, head of the Institute for Mummy Studies in Bolzona, Italy, told Business Insider the ancient Egyptians are thought to have had an adept understanding of medical practices. “They wouldn't have known things we would now take for granted, like how a heart functions, how microbes cause infection, or how rogue cells cause cancer — but they did have a fairly good idea of how to treat symptoms of disease, Zink said. "We know from other evidence, like papyrus, that they had a good experience of treating wounds and injuries," said Zink. [Source: Marianne Guenot, Business Insider, January 14, 2022]

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “Medical papyri, spells for healing, and physical anthropology are three sources for understanding the body and disease in ancient Egypt. There was minimal allowance in Egyptian art for the representation of disease or deformity... Illness, aging, and, after death, putrefaction were conceptualized in the Egyptian world-view as bodily problems that could be countered by healing, fertility and rejuvenation, and the process of mummification, thereby restoring function and wholeness to the human body.” [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Studies have shown that providing clean water and sanitation can bring about tremendous benefits. People live longer, stay healthier and become productive while health care costs go down. People have realized the importance of clean water for some time. A tomb from ancient Egypt dated to 1450 B.C. depicts an elaborate filtering system. The ancient Greeks and especially the Romans devoted a lot of energy and resources to clean water.

Ancient Egyptian Medical Knowledge and Mummification

ancient Egyptian medical tools

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The Egyptians were advanced medical practitioners for their time. They were masters of human anatomy and healing mostly due to the extensive mummification ceremonies. This involved removing most of the internal organs including the brain, lungs, pancreas, liver, spleen, heart and intestine. The Egyptians had (and this is an understatement) a basic knowledge of organ functions within the human body (save for the brain and heart which they thought had opposite functions). This knowledge of anatomy, as well as (in the later dynasties) the later crossover of knowledge between the Greeks and other culture areas, led to an extensive knowledge of the functioning of the organs, and branched into many other medical practices. Further, it was not uncommon in both early and later dynasties for scholars from ancient Greece and other parts of the Mediterranean to study the medical practitioners of Ancient Egypt. Of the most notable of these traveling scholars was, Herodotus and Pliny, both Greek scholars, whose contribution to the ancient and modern medical records, reached from the time of Ancient Egypt and into the modern era. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Though the Egyptians were effective healers, they did not have a clear knowledge of cellular biology or of germ theory, so it would be inappropriate to attribute the use of Yeast's as an antibiotic; as the curative effects behind the use of antibiotics were not known until well into modern times. Yet one must admire the ingenuity of the Egyptians, which undoubtedly has it's place within the compendium of human medical history. The largest of these medicinal compendiums was compiled by Hermes (a healer of Greek origin who studied in Egypt), and consisted of six books. The first of these six books was directly related to anatomy, the rest served as a book of physic, and as apothecaries. Though Hermes was not the first to compile much of the information about Egyptian medical practices, beginning early on with the pharaoh Athothes (the second king of Egypt), the Egyptians are credited with being the first to use and record advanced medical practices. +\

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “The anatomical knowledge gained through the practice of mummification may have contributed to Egyptian conceptions of the sectioned or fragmented body, and it certainly informed Egyptian medical practices. Evidence from medical papyri and from surviving mummies reveals that the Egyptians recognized the role of the brain, were generally familiar with blood circulation, and could treat wounds and broken limbs, and nurture the physically disabled or frail. Gynecological health is a concern of medical papyri from el-Lahun, suggesting that male doctors sometimes treated female patients; however, as in almost all traditional cultures, childbirth was probably attended only by women. The bodily processes of gestation, birth, and breastfeeding were the basis of some elite cultural formulations in visual culture and ritual activities, such as the iconography of Isis and Horus, and perhaps the performance of the Opening of the Mouth. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Health Care Planfor Ancient Egyptian Workers

Stanford archaeologist Anne Austin is involved in the excavation of the artisans village of Deir el-Medina, near Luxor and the Valley of the Kings, where she told the Washington Post residents were beneficiaries of what she calls "the world's first documented health-care plan" with paid sick leave, medical rations and a state-supported physician. "There was definitely a lot of paperwork we still don't understand the purpose of, or why it has the level of detail that it does," Austin told The Post, noting that exacting documentation of worker sick days, for example, is not always reflected by a deduction in their pay. "It seems like they were documenting things because they had to record them, but not necessarily because they planned to use the information." [Source: Peter Holley, Washington Post, November 22, 2014 ]

Austin — at the time a postdoctoral scholar in Stanford's history department and a specialist in osteo-archaeology — was able to determine that the grueling work took a serious toll on the men's bodies. Peter Holley wrote in the Washington Post: Making the weekly hike from their family homes to a temporary work camp in Deir el-Medina was equivalent to climbing the Great Pyramid of Giza, due to steep changes in elevation. Their daily trek, with gear and equipment, into the Valley of the Kings and back, was the same as descending and ascending a 36-story building, Austin said. Today, the distance is about 1,000 stone steps. "Arthritis is something you could easily see in the bones," Austin said. "It was mostly concentrated in the workers' knees and ankles."

pressure-produced anasthesia

Despite access to this "uniquely comprehensive health care," workers didn't always take advantage of it, Austin said. One man continued working despite suffering from a condition known as osteomyelitis, the result of a blood-borne infection. Austin was able to determine the man had the condition by studying his mummified remains. "The remains suggest that he would have been working during the development of this infection," Austin told Stanford News. This suggested that the man might have felt pressure to continue. "Rather than take time off, for whatever reason, he kept going," she said.”

Austin wrote in The Conversation: In some cases the workmen were actually working through their illnesses. For example in one text, the workman Merysekhmet attempted to go to work after being sick. The text tells us that he descended to the King’s Tomb on two consecutive days, but was unable to work. He then hiked back to the village of Deir el-Medina where he stayed for the next ten days until he was able to work again. Though short, these hikes were steep: the trip from Deir el-Medina to the royal tomb involved an ascent greater than climbing to the top of the Great Pyramid. Merysekhmet’s movements across the Theban valleys were likely at the expense of his own health. This suggests that sick days and medical care were not magnanimous gestures of the Egyptian state, but were rather calculated health care provisions designed to ensure that men like Merysekhmet were healthy enough to work. [Source: Anne Austin, Assistant Teaching Professor, University of Missouri-St. Louis, The Conversation, May 3, 2021]

Paid Sick Leave for Ancient Egyptian Workers

The workers at Deir el-Medina were highly skilled craftsmen hired to build tombs for Egyptian pharaohs. “Workers who spent their weeks away from home... could take "paid sick leave" or "visit a clinic for a checkup," Austin said. During the 19th dynasty of Egypt and the 12th (1292-1077 B.C.), when workers were primarily housed in the area, there were even two separate health-care networks at Deir el-Medina, Austin told the Stanford News. The first was a "professional state-subsidized network" for workers; the other was a private network for family and friends. [Source: Peter Holley, Washington Post, November 22, 2014 ]

“"What surprised me was seeing the ways people who were associated with the workmen were provided for," Austin said. "There is evidence to suggest work men would get time off to take care of wives and daughters when they were menstruating.""For decades," according to a Stanford news release, "Egyptologists have seen evidence of these health-care benefits in the well preserved written records from the site." But Austin was the first to lead a "detailed study of human remains at the site."

Austin wrote in The Conversation: “The village was allotted extra support: the Egyptian state paid them monthly wages in the form of grain and provided them with housing and servants to assist with tasks like washing laundry, grinding grain and porting water. Their families lived with them in the village, and their wives and children could also benefit from these provisions from the state. [Source: Anne Austin, Assistant Teaching Professor, University of Missouri-St. Louis, The Conversation, May 3, 2021]

Among these texts are numerous daily records detailing when and why individual workmen were absent from work. Nearly one-third of these absences occur when a workman was too sick to work. Yet, monthly ration distributions from Deir el-Medina are consistent enough to indicate that these workmen were paid even if they were out sick for several days. These texts also identify a workman on the crew designated as the swnw, physician. The physician was given an assistant and both were allotted days off to prepare medicine and take care of colleagues. The Egyptian state even gave the physician extra rations as payment for his services to the community of Deir el-Medina.

Family Served as Social Safety Net in Ancient Egypt

Anne Austin wrote in The Conversation: In cases where these provisions from the state were not enough, the residents of Deir el-Medina turned to each other. Personal letters from the site indicate that family members were expected to take care of each other by providing clothing and food, especially when a relative was sick. These documents show us that caretaking was a reciprocal relationship between direct family members, regardless of gender or age. Children were expected to take care of both parents just as parents were expected to take care of all of their children. [Source:Anne Austin, Assistant Teaching Professor, University of Missouri-St. Louis, The Conversation, May 3, 2021]

“When family members neglected these responsibilities, there were fiscal and social consequences. In her will, the villager Naunakhte indicates that even though she was a dedicated mother to all of her children, four of them abandoned her in her old age. She admonishes them and disinherits them from her will, punishing them financially, but also shaming them in a public document made in front of the most senior members of the Deir el-Medina community.

“This shows us that health care at Deir el-Medina was a system with overlying networks of care provided through the state and the community. While workmen counted on the state for paid sick leave, a physician, and even medical ingredients, they were equally dependent on their loved ones for the care necessary to thrive in ancient Egypt.

Doctors in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians were one of the first people to have practicing physicians. The oldest known physician, Imhotep, lived around 2725 B.C. He was also a high official, the designer of famous Step Pyramid and astrologer who achieved such high status that he made into a god. The Egyptians had dentists and obstetricians. Egyptian physicians often specialized in a specific part of the body, such as the stomach, eyes and bowels.[Source: Page of Egyptian Medicine ~]

court physician Niankhre

Egyptian doctors were fairly knowledgeable about the human body. They studied the structure of the brain, and knew that the pulse was related to the heart. They could cure many illnesses and set broken bones. There is evidence Doctors in Ancient Egypt underwent years of training at temple schools in areas such as interrogation, inspection, and palpation. Some surgery was done. Skulls with holes in them have been found. ~

Like modern doctors, Ancient Egyptian doctors gave out prescriptions for medicines. One from the Ptolemaic era, written in Greek, contained lead monoxide as one of its ingredients.

Surgical tools used by a Egyptian doctors included: knives, adrill, saw, forceps or pincers, censer, hooks, bags tied with string, beaked vessel, vase with burning incense, Horus eyes, scales, pot with flowers of Upper and Lower Egypt, pot on pedestal, graduated cubit or papyrus, scroll without side knot (or a case holding reed scalpels), shears, spoons. ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024