CRIME IN ANCIENT EGYPT

stuff in the tomb of Tutankhamun (King Tut), looting of royal tomb in Ancient Egyptian times was a crime punishable by death

Crimes in ancient Egypt tended to be divided into two categories: 1) crimes against the state scuh as desertion, treason, and slandering the pharaoh; and 2) crimes against individuals such murder, homicide, injury, robbery, and theft[Source: Irene Cordón, National Geographic, January 30, 2019]

According to a University of Oxford course outline: Many crimes are attested in the sources, including burglary, fraud, tax evasion, murder and tomb robbery. Personal offences were often settled informally between the disputants with the help of respected members of the village. For civil cases, such as matters relating to property rights, the local villagers formed a court called a kenbet. In a land without lawyers, the claimant had to make his own case and question the defendant. At the end of proceedings, the court simply announced that ‘X is right, Y is wrong’. The court had no power to ensure that the judgement was fulfilled, and instead relied on social pressure; guilt had to be admitted and the judgement accepted. Oracles of the gods could also be approached to judge cases.

It seems that most crime was of a petty nature. One 18th Dynasty texts reads: “They went to the granary, stole three great loaves and eight sabu-cakes of Rohusu berries. They drew a bottle of beer which was cooling in water, while I was staying in my father’s room. My Lord, let whatsoever has been stolen be given back to me.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN JUSTICE SYSTEM factsanddetails.com ;

COURTS OF LAW IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LEGAL PROCEDURES IN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN COURTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LAW ENFORCEMENT IN ANCIENT EGYPT: POLICE, INVESTIGATIONS, PUNISHMENTS, TORTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Harem Conspiracy: The Murder of Ramessess III” by Susan Redford (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Murder of Tutankhamen: A True Story” by Bob Brier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Law in Ancient Egypt” by Russ VerSteeg (2002) Amazon.com;

“Maat Revealed, Philosophy of Justice in Ancient Egypt” by Anna Mancini (2007) Amazon.com;

”Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians: Volume 1: Including their Private Life, Government, Laws, Art, Manufactures, Religion, and Early History (Cambridge Library Collection - Egyptology) by John Gardner Wilkinson (1797–1875) Amazon.com;

“Judgement of the Pharaoh: Crime and Punishment in Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley

Amazon.com;

“State in Ancient Egypt, The: Power, Challenges and Dynamics” by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia (2019) Amazon.com;

Murder and Violent Crimes in Ancient Egypt

Kerry Muhlestein of Brigham Young University wrote: “Rape, domestic violence, and even murder are attested at the village. These illicit acts of violence were viewed, at least by some, in a negative light, for we learn about them in the form of complaints. From three letters of the Late Ramesside era we recover hints of a plot to kill two Medjay apparently in order to keep them from testifying in some manner against the perpetrators. The secrecy of the plot makes it clear that this act would be looked upon most unfavorably, even though people of power were involved. Record s of legal proceedings also hint at violence, such as the acts attempted in connection with the harem conspiracy in the reign of Ramesses. These records may give us a clue as to what Weni, an Old Kingdom official, meant when he enigmatically spoke of hearing a secret matter in the harem, but we cannot know. Similarly, the Persian Period Petition of Petiese outlines a case of murder, giving us a small insight into violent events that must have happened throughout Egyptian history. Royal decrees can provide traces of violent acts among non-royal individuals. [Source: Kerry Muhlestein, Brigham Young University, 2015, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“For example, when the 21 st Dynasty Banishment Stela stipulates that murder was worthy of death, we may safely assume that murder was not an unknown act. Similarly, a Demotic literary tale, which culminates in the burning of murderers, implies that such things happened in reality as well, as does a literary tale from the 21 st Dynasty, which recounts the murder of a woman and scattering of her children. Other literary tales portray violence in a negative light, such as when a minor official is portrayed as beating a peasant in such a way that the beating is clearly viewed as unjustifiable and wrong. One of the most profitable sources for learning about violence are oracular texts. For exam ple, we can read of death being decreed by oracle for embezzlers.

“When trials were decided by appeals to oracles, often the deeds of the accused were either written on a text presented to the oracle, or the oracle’s decision was writt en down. From these kinds of texts we learn of two boys who were beaten to death and of the execution of their murderers. In another we learn of two men who had been caught in illegal acts trying to murder the man who had discovered them before he could tell anyone. While the official writings of Egypt do not present us with the illicit violence that could be a part of lived experience, such acts become more apparent in their laundry lists.

“Clearly murder, or killing someone who was innocent, was viewed as wrong. Piankhy forbade certain men from entering a temple because they “did a thing which god did not command should be done, they conceived evil in their hearts, even slaying one who was without guilt”. “While it is clear that such killing was outside of what the divine and mortal realms sanctioned, it is curious that the punishment, apparently for attempted or at least plotted murder, appears to be so mild. At least in this writing the only punishment listed was a prohibition from entering the temple. This may be due to Piankhy’s concentration on purity, for he emphasized that these men had done the killing within the very temple they were forbidden to enter. In a literary na rrative, the Tale of the Two Brothers , even a king killing one who was innocent is portrayed negatively. The Myth of the Eye of the Sun more clearly depicts the negative view of those who murdered. In one conversation it is recorded that th ose who kill should be killed, and that those who go unpunished will never have the blood removed from them and will be punished eventually, even if it is in the next life.

“While in formal complaints or actions, grievous offenses such as adultery were not typically punished by violence, some texts might imply that this could happen on occasion, and a few wisdom texts intimate that it was not unheard of for the wronged spouse to seek illicit retribution.”

Women and Crime in Ancient Egypt

Peter A. Piccione wrote: “These ordinary and extraordinary roles are not the only ones in which we see Egyptian women cast in ancient Egypt. We also see Egyptian women as the victims of crime (and rape); also as the perpetrators of crime, as adulteresses and even as convicts. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“Women criminals certainly existed, although they do not appear frequently in the historical record. A woman named Nesmut was implicated in a series of robberies of the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the Twentieth Dynasty. Examples of women convicts are also known. According to one Brooklyn Museum papyrus from the Middle Kingdom, a woman was incarcerated at the prison at Thebes because she fled her district to dodge the corvee service on a royal estate. Most of the concubines and lesser wives involved in the harim conspiracy against Ramesses III were convicted and had their noses and ears cut off, while others were invited to commit suicide. Another woman is indicated among the lists of prisoners from a prison at el-Lahun. However, of the prison lists we have, the percentage of women's names is very small compared to those of men, and this fact may be significant.” -

Ancient Egyptian Looters

Nearly all the tombs of pharaohs and ancient Egyptian noblemen and priest have been looted, many of them soon after they were built. Many are believed to be have been much grander than the tomb of King Tutankhamun and contained much more impressive funerary objects. The grand objects were found in Tutankhamun’s tombs even though it most of its rooms had been looted.

During the 20th and 21st dynasties, looting was quite common. In some cases the mummies of pharaohs were moved to new locations and looters left behind graffiti that helped archaeologists place when the deeds were done. Owing to their isolated position in the bare desert valley, the violation of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings and elsewhere occurred and officials confessed openly that they were powerless against the thieves. They were obliged to abandon the tombs which were exposed to danger, and to try only to save the royal bodies; even these were somewhat injured and had to be restored as well as possible. Distracted by fear, they dragged the bodies from tomb to tomb; such as the mummy of Ramses II. was first placed in the tomb of Seti I., and when that tomb was threatened, in that of Amenhotep I. Finally there was nothing further to be done but in the darkness of the night to bring the bodies that remained, and hide them in an unknown deep rocky pit in the mountains of Der-el-bahri. So greatly did they fear the thieves that the priests no longer dared to inter in state the mummies of the royal house, but hid them also in this hidingplace. They were well concealed there.All the great monarchs of the New Kingdom — Ahmose I, who expelled the Hyksos, the sacred queen Ahmose-Nefertari, Amenhotep I., Thutmose II., Thutmose III. the great conqueror, Seti I., the great Ramses II. and many others rested here unmolested until the 19th century. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

A fragment of 3,000-year-old papyrus in Turin, Italy recounts the trial of a thief who confessed after torture to breaking in to the tombs of Ramses the Great and his children. The looters pried open sarcophaguses, unwrapped mummies and smashed everything in efforts to find hidden treasures. Mummies often had huge holes hacked in the chests and their face that were in all likelihood made by looters in search of treasures. In the age of the pharaohs, the tombs were guarded by priests and the punishment for looters was being impaled alive, condemned to the "flame of Skehment" or "f**ked" by donkeys. Still some looters took the risk.

Ramesside Tomb Robberies

Tomb of Ramses II

The Ramesside Tomb Robberies refers to the alleged looting of the tombs of nobles in the Valley of the Kings around 1,100 B.C. The Abbott Papyrus describes a search of the tombs claimed by an official named Pawero to have been violated. A commission searched ten royal tombs, four tombs of the Chantresses of the Estate of the Divine Adoratrix, and finally the tombs of the citizens of Thebes. The result of the search was that the tomb of King Sobekemsaf II, two out of the four tombs of the Chantresses of the Estate of the Divine Adoratrix, and all of the citizen tombs were disturbed. After this there was another search of tombs in the Valley of the Queens and the tomb of Queen Isis. Those in charge of this search brought along a coppersmith named Peikharu who confessed to stealing from the tomb of Isis and tombs from the Valley of the Queens. During the search the coppersmith could not point to the tombs he violated, even after being brutally beaten. [Source Wikipedia]

There were eight thieves who had violated the tomb of King Sobekemsaf II, most of them were servants in the temple of Amun. Amongst them were masons, and apparently these had forced the subterranean way into the interior of the tomb. They “were examined," that is “they were beaten with sticks both on their hands and feet; “under the influence of this cruel torture they confessed that they had made their way into the tomb and had found the bodies of the king and queen there. They said: “We then opened the coffins and bandages in which they lay. We found the noble mummy of the king . . . with a long chain of golden amulets and ornaments round the neck; the head was covered with gold. The noble mummy of this king was entirely overlaid with gold, and his (coffin) was covered both inside and out with gold, and adorned with precious jewels. We tore off the gold, which we found on the noble mummy of this god, as well as the amulets and ornaments from round the neck, and the bandages in which the mummy was wrapped. We found the royal consort equipped in like manner, and we tore off all that we found upon her. We burnt her bandages, and we also stole the household goods which we found with them, and the gold and silver vessels. We then divided all between us; we divided into eight parts the gold which we found with this god, the mummies, the amulets, the ornaments, and the bandages. " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Three years later, about sixty arrests were made of persons supposed to be thieves. Those who fell under suspicion this time were not poor serfs, but, for the most part, officials of a low rank amongst whom we even find a scribe of the treasury of Amun, a priest of Amun, and a priest of Khons. Many of the others were “out of office," such as a “former prophet of the god Sobek," from Peronch, a town in the Faiyum, probably a fictitious personage. Most of the thieves were of course Thebans, others had come from the neighbouring places for the sake of this lucrative business. They did not rob the same part of the necropolis as their predecessors of the 16th year, but turned their attention to the barren valley now called the Valley of the Kings. Here they robbed the outer chambers of the tombs of Ramses II. and Seti I., and sold the stolen property; their wives, who were also arrested, may have been their accomplices in this matter. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The Berlin museum actually possesses an object which in all probability belonged to their plunder — a bronze funerary statuette of King Ramses II. The thieves broke off the gold with which it was overlaid, and flattened and mutilated the graceful figure; they then threw away the bronze as worthless into some corner, where by a happy chance it was preserved to us. The robbery might not have been discovered had not the thieves finally quarrelled over the division of the spoil, and one of them, who thought himself ill used, went to an officer of the necropolis and denounced his coinrades.

See Investigation of the Ramesside Tomb Robberies Under LAW ENFORCEMENT IN ANCIENT EGYPT: POLICE, INVESTIGATIONS, PUNISHMENTS africame.factsanddetails.com

Ramesside Tomb Robberies Papyri

The Ramesside tomb-robbery papyri, Papyrus Turin 1887 records the “Elephantine scandal.” It shows in detail the complex network of complicity between the thieves and government officials and sheds light on the realities of life in ancient Egypt, where crimes and despicable acts don’t seem that unusual. One of the robbers melted stolen gold in the house of an accomplice, a priest of Ptah. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno García, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

On the text, J.H. Breasted wrote: “These two documents are the court records of the prosecution of the tomb-robbers, whose names are recorded on the back of the Papyrus Abbott, in the first year of Ramses X (nineteenth of Ramses IX), and of others in the next year, eight months later.” The second text “follows the trial of five men, with the usual formulae, only slightly varied from” the first one. “The tomb which they were accused of robbing is not mentioned. All five were found innocent. The prosecutions...do not refer to any particular tombs, but they are followed in turn by a list, headed: "Year 2, first month of the first season, day 13; the names of the robbers of the tomb of Pharaoh." This list contains the names of twenty-two persons (two women), among whom are some of those prosecuted.

“After a gap of a few lines Column 8 proceeds with an important trial, of which the beginning is lost in the gap....After enumerating some of the things stolen, in response to a question of the vizier, the examination of the next man shows him to have been innocent. The fisherman who carried the thieves over to the west side is next examined and discharged; and of the three men whose trial follows, one was innocent. A list of twenty-five thieves fills the next column which is headed: "The thieves of the cemetery whose examination was held, concerning whom it was found that they had been in the tombs." Column 11 contains a similar list entitled: "The thieves of the tomb, in the second month, tenth day," while the margin bears a list of "the women who were imprisoned," being eleven of the wives of the thieves. The document then closes with proceedings in which some of the accused in the first trial reappear. The second document (Papyrus Mayor B) is in a different hand, but records proceedings of the same sort. In a connection which is not entirely clear, the tomb of "Amenhotep III, the Great God," is mentioned, and it is evident that it had been robbed.”

Ramesside Tomb Robberies Texts

The Ramesside tomb robberies in The Mayer Papyri; the first text reads: “Year 1, of Uhem-mesut (whm-ms.wt), fourth month of the third season, day 13. On this day occurred the examination of the thieves of the tomb of King Usermare-Setepnere (Ramses II)... in the treasury of "The-House-of-King-Usermare-Meriamon (Ramses III),-L.-P.-H.", concerning whom the chief of police, Nesuamon, had reported, in this roll of names; for he was there, standing with the thieves, when they laid their hands upon the tombs; who were tortured at the examination on their feet and their hands, to make them tell the way they had done exactly. -

“The Aaa, Paykamen (pAj-kAmn), under charge of the overseer of the cattle of Amon, was brought in; the oath of the king, L. P. H., was administered to him, not to tell a lie. He was asked: "What was the manner of thy going with the people who were with thee, when ye robbed the tombs of the kings which are [recorded (?)] in the treasury of"The-House-of-King-Usermare-Meriamon,-L.-P.-H."? He said: "I went with the priest Teshere (tA-Srj), son of the divine father, Zedi, of 'The House;' Beki, son of Nesuamon, of this house; the Aaa, Nesumontu of the house of Montu, lord of Erment; the Aaa, Paynehsi of the vizier, formerly prophet of Sebek of Peronekh (pr-anx); Teti (tA-tj) [///] who belonged to Paynehsi, of the vizier, formerly prophet of Sebek of Peronekh; in all six."

“The chief of police, Nesuamon, was brought in. He was asked: "How didst thou find these men?" He said: "I heard that these men had gone to rob this tomb. I went and found these six men. That which the thief, Paykamen, has said is correct. I took testimony from them on that day. The examination of the watchman of the house of Amon, the thief, Paykamen, under charge of the overseer of the cattle of Amon, was held by beating with a rod, the bastinade was applied to his feet. An oath was administered to him that he might be executed if he told a lie; he said: 'That which I did is exactly what I have said.' He confirmed it with his mouth, saying: 'As for me, that which I did is what [they] did; I was w[ith the]se six men, I stole a piece of copper therefrom, and I took possession of it.'"

Tomb of Ramses II

“The Aaa, the thief, Nesumontu,was brought in; the examination was held by beating with a rod; the bastinade was applied on (his) feet and his hand(s); the oath of the king, L. P. H., was administered to him, that he might be executed if he told a lie. He was asked: "What was the manner of thy going to rob in the tomb with thy companions?" He said: "I went and found these people; I was the sixth. I stole a piece of copper therefrom, I took possession of it." -copper: Breasted: mAjw, with determinative of metalThe watchman of the house of Amon, the Aaa, Karu (qA-rw), was brought in; he was examined with the rod, the bastinade was applied to his feet and his hands; the oath of the king, L. P. H., was administered to him, that he might be executed if he told a lie. He was asked: "What was the manner of thy going with the (sic !) companions when ye robbed in the tomb?"

“He said: "The thief, the Aaa, Pehenui, he made me take some grain. I seized a sack of grain, and when I began to go down, I heard the voice of the men who were in this storehouse. I put my eye to the passage, and I saw Paybek and Teshere, who were within. I called to him, saying, 'Come!' and he came out to me, having two pieces of copper in his hand. He gave them to me, and I gave to him 1½ measures of spelt to pay for them. I took one of them, and I gave the other to the Aaa, Enefsu (an.f-sw). The priest, Nesuamon, son of Paybek, was brought in, because of his father. He was examined by beating with the rod. They said to him: "Tell the manner of thy father's going with the men who were with him."

“He said: "My father was truly there. I was (only) a little child, and I know not how he did it." On being (further) examined, he said: "I saw the workman, Ehatinofer (aHAtj-nfr), while he was in the place where the tomb is, with the watchman, Nofer, son of [Merwer {Mr-wr)] and the artisan, in all three (men). They are the ones I saw distinctly. Indeed, gold was taken, and they are the ones whom I know." On being (further) examined with a rod, he said: "These three men are the ones I saw distinctly."

“The weaver of "The House," Wenpebti (wn-pHtj)... was brought in. He was examined by beating with a rod, the bastinade was applied to his feet and his hands. The oath of the king, L. P. H., was administered, not to tell a lie. They said to him: "Tell what was the manner of thy father's going, when he committed theft in the tomb with his companions." He said: "My father was killed when I was a child. My mother told me: 'The chief of police, Nesuamon, gave some chisels of copper to thy father, then the captains of the archers and the Aaa slew thy father.' They [held ] the examination, and Nesuamon took the copper and gave it to [me ]. It remains [in the possession of ] my mother."

“A Theban woman, Enroy (jn-n-rA-j), the mistress of the priest, Teshere, son of Zedi, was brought in. She was examined by beating with a rod; the bastinade was applied to her feet and her hands. The oath of the king, L. P. H., not to tell a lie, was administered to her; she was asked: "What was the manner of thy husband's going when he broke into the tomb and carried away the copper from it?" She said: "He carried away some copper belonging to this tomb we sold it and devoured it."

The second text reads: Fourth month of the third season, day 17; was held the examination of certain of the thieves of the cemetery....He was again examined by beating with a rod. They said to him: "Tell what were the other places which thou didst break into."...He said: "I broke into the tomb of the King's-Wife, Nesimut."...He said: "It was I who broke into the tomb of the King's-Wife, Bekurel (bk-wr-n-rA), wife of King Menmare (Seti I), L. P. H., in all, three (tombs)."

Murder Attempt by Ptolemaic-Era Twins

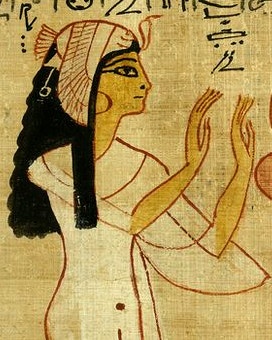

sculpture of the god Orisis making Isis pregnant after he was murdered

John Ray of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: ““The lives of Tawe and her twin sister Taous are known from a remarkable series of papers written in Greek and Egyptian during the middle years of the second century B.C. The texts were found in the sands of Saqqara-some of those concerning the twins are in the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Thanks to this archive, we know some details of the sisters' early life. At first, they lived with in Memphis. Their mother left their father for a Greek soldier, named Philippos. The couple plotted to murder the father, and staged an attempt on his life. The father escaped, but went back to his home in Middle Egypt, where he died of grief. The mother was wealthy, but sold the family home and evicted the twins. |::|

“Rescue came from a Macedonian Greek named Ptolemaios, an intriguing character who spent much of his life as a recluse near the temple of the Serapeum, at Saqqara. He persuaded the temple authorities to give the twins jobs as temple acolytes, where their duty was to impersonate the sister-goddesses Isis and Nephthys. Even this was not the end of their troubles, since their half-brother, aided by the malicious mother, embezzled their salary. |::|

“We have a large number of Ptolemaios' papers, many concerned with the problems of the twins, who feature even in his dreams. Another person important in their lives is Ptolemaios' brother Apollonios, a volatile adolescent with an ambiguous attitude towards the beliefs of his relative. Sometimes Apollonios seems a model of piety, at other times he rejects the gods in a way that seems utterly modern. Apollonios had the gift of making enemies among the Egyptians who peopled the area of the Serapeum.” |::|

An “account of a dream shows many of the preoccupations of Tawe and her sister. The figure of the mother, the setting of the riverbank murder-attempt, the subject of marriage, and the question of mutual affection, are all themes. The papers of Ptolemaios, Apollonios, and the temple twins are the most intimate records to come down to us from antiquity, and they deserve to be known, not merely by scholars, but by people worldwide.” |::|

Violence in Ancient Egypt

Kerry Muhlestein of Brigham Young University wrote: “Throughout time, Egyptian sources display divergent attitudes towards violence expressing the belief that some situations of violence were positive and to be encouraged, while others were to be avoided. Sanctioned violence could be employed for a variety of reasons—the severity of which ranged from inflicting blows to gruesome death. Violence was part of the preternatural realm, notably as Egyptians attempted to thwart potential violence in the afterlife.While the average Egyptian was supposed to eschew violence, kings and their representatives were expected to engage in violent acts in many circumstances. Improper violence disturbed order while sanctioned violence restored it. While the types of sanctioned violence employed and the reasons for employing it changed over time, some attitudes about violence remained constant. more about later periods rather than earlier. We must use caution when retrojecting later views about violence to earlier periods, though often, all we have is later evidence. These considerations notwithstanding, when we examine all the data available, we can accumulate a fair view of Egypt’s attitude towards and experience of violence. [Source: Kerry Muhlestein, Brigham Young University, 2015, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

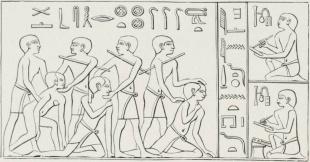

slave beating

“The earliest religious texts are replete with references to preternatural violence, a practice which remains consistent throughout Egyptian civilization. The Pyramid Texts contain numerous references to the violence of gods, many of which pertain to incidents for which we have later narratives. Even among the gods we are presented with a bifurcated view of violence. According to many texts, th e first act to disturb order was an act of violence, whether it be the slaying and mutilation of Osiris or some kind of rebellion among mankind and a consequent violent response from a deity. These unsanctioned acts of violence were abhorrent, yet they were set aright by a violent response. In the case of Osiris’ slaying, order was eventually restored after Horus defeats Seth in a violent battle that, in some versions, included spearing, decapitation, gouging eyes out, rape, and threats of killing other gods . Mankind was punished for its rebellion by near-destruction (the Myth of the Heavenly Cow).

The Instructions for Merikara tell us the creator slew his own children when they contemplated rebelling against him. Texts about deities are replete with descriptions of driving away or slaughtering enemies of gods, with frequent reference to the slaughterhouse of the gods as a place to send these enemie s (e.g., the Book of the Dead : BD 1B). While such violent enemies represent chaos, their violent destruction represents a restoration of order. This battle often becomes personified, such as the ongoing battle between Apophis and the Sun God, or as in accounts of Seth stabbing and spearing the Chaos serpent.”

“However violent reality was, it pales in comparison to the violence potentially experienced as part of the afterlife. From the earliest funerary literature to the latest, the afterlife was depicted as a place fraught with violence. Thus, the texts appropriately contained instructions and spells aimed at avoiding it. There are repeated references to divine slaughterhouses and to gods slaughtering men. A frequent theme is wishing to avoid those who beat with sticks, or who cut off heads, stab, entrap, or mutilate. Frequently in the afterlife, gates present fearsome guardians with knives who await those who are unprepared. Ultimate violence, the second death, was an afterlife possibility all sought to avoid. Yet these texts si multaneously depict the need for violence, such as various gods, or even the dead, slaying multifarious enemies on behalf of themselves or others. Violence filled the afterlife, but the potential for an individual to avoid this violence was also present.

“Our greatest barrier to understanding violence in ancient Egypt is the reticence, which sources express towards the recording of illicit acts of violence. This in and of itself indicates something of attitudes towards violence. In general, while we know violence existed, private actions were supposed to avoid violence. Undoubtedly, however, sanctioned violence, or violence deemed as appropriate, permeated most aspects of Egyptian society. This led to a higher level of reg ular violence than in many modern cultures. While sanctioned violence was seen as a regular and necessary part of life, and illicit violence obviously occurred, Egypt’s stated cultural values of eschewing unsanctioned violence, or even anger, is a clearly held value that influenced society.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024