ANCIENT GREEK TECHNOLOGY

Byzantine-era Greek fire flamethrower

The Greeks made many technological advances. Some of the greatest advances were made by the Hellenistic Greeks, who among things made hand-shaped nutcrackers from bronze and employed screw-like helixes to make primitive odometers and water pumps. Ceramics created by the Greeks were far superior to anything made by civilizations that preceded it. Greeks in Alexandria developed the first steam-powered device. Ctesibius of Alexandria (second century B.C.) invented a hydraulic organ and a water clock with a floating indicator to mark the time on a vertical scale.

Just as war drove significant improvements in medical practices so, too, did it have an impact on the field of engineering. Scholars such as Archimedes became military engineers, inventing and improving defensive and offensive weapons. There were, in addition, other innovations such as the gear, the screw, the steam engine, the screw press and so on but the prevailing Greek attitude towards manual labor and labor-saving devices did not greatly encourage nor reward innovation (except in the military sphere) so many inventions remained curiosities rather than instruments of change. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

More than 2,000 years ago, the residents of Crete used a form of computer for calculating calendars based on the motions of the sun and the moon. The Roman orator Cicero wrote of a instrument made by the first century B.C. scholar Posidonius of Rhodes that "at each revolution reproduces the same motions of the Sun, the Moon and the five planets that take place in the heavens every day and night."

RELATED ARTICLES:

SCIENCE IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MATHEMATICS IN ANCIENT GREECE: GEOMETRY, MEASUREMENTS, THEOREMS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ASTRONOMY IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TIME IN ANCIENT GREECE: CLOCKS, DIVISIONS, DAYS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ATOMISTS: LEUCIPPUS AND DEMOCRITUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece and Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Greek and Roman Technology: A Sourcebook of Translated Greek and Roman Texts” (Routledge) by Andrew N. Sherwood, Milorad Nikolic , et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Technology: A Sourcebook of Translated Greek and Roman Texts” (Routledge) by Andrew N. Sherwood, Milorad Nikolic, John W. Humphrey Amazon.com;

“Greek Fire, Poison Arrows and Scorpion Bombs” by Adrienne Mayor (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Works of Archimedes” (Dover Books on Mathematics)

Amazon.com;

“The Archimedes Codex: How a Medieval Prayer Book Is Revealing the True Genius of Antiquity's Greatest Scientist” by Reviel Netz, William Noel (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Illustrated Method of Archimedes: Utilizing the Law of the Lever to Calculate Areas, Volumes, and Centers of Gravity” (2012) Amazon.com;

“Decoding the Mechanisms of Antikythera Astronomical Device” by Jian-Liang Lin, Hong-Sen Yan (2016) Amazon.com;

“A Portable Cosmos: Revealing the Antikythera Mechanism, Scientific Wonder of the Ancient World” by Alexander Jones Amazon.com;

“Decoding the Heavens: A 2,000-Year-Old Computer-and the Century-long Search to Discover Its Secrets” by Jo Marchant (2010) Amazon.com;

“Mining and Metallurgy in the Greek and Roman World” by John F Healy (1978) Amazon.com;

“Technology and Culture in Greek and Roman Antiquity” by S. Cuomo (2007) Amazon.com;

“Technology and Society in the Ancient Greek and Roman Worlds” by Tracey Elizabeth Rihll (2013) Amazon.com;

"Ancient Inventions” by Peter James and Nick Thorpe (Ballantine Books, 1995) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Science” by Liba Taub (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Time Museum, Volume I, Time Measuring Instruments; Part 3, Water-clocks, Sand-glasses, Fire-clocks” by Anthony J. Turner (1984) Amazon.com;

“Time Museum Catalogue of the Collection: Time Measuring Instruments, Part 1 : Astrolabes, Astrolabe Related Instruments” (1986) by A. J. Turner Amazon.com;

“The Genesis of Science: The Story of Greek Imagination” by Stephen Bertman (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Greece and Rome (Blackwell) by Georgia L. Irby (2016) Amazon.com;

“Introducing the Ancient Greeks: From Bronze Age Seafarers to Navigators of the Western Mind” by Edith Hall Amazon.com;

“Greek Science of the Hellenistic Era: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Georgia L. Irby-Massie (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World” by Charles Freeman (2000) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek and Roman Science: A Very Short Introduction”

by Liba Taub Amazon.com;

“Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle” by G. E. R. Lloyd (1974) Amazon.com;

“The Library of Alexandria: Centre of Learning in the Ancient World” by Roy MacLeod | (2004) Amazon.com;

“Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science – from the Babylonians to the Maya” by Dick Teresi (2010) Amazon.com;

Ancient Greek Mythology, Philosophy and Technology

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The most talented craftsman in ancient thought was undoubtedly Hephaestus, the god of the forge. Not only did he make Talos [a bronze giant that guarded the coast of Cretee against pirates] he helped craft Pandora (who is shown in ancient artwork as almost mechanically stilted), and had his own team of “living statues” of golden handmaidens. In the Iliad, when Thetis goes to visit Hephaestus in his workshop she observes the maidens who “moved quickly, bustling around their master like living women.” Hephaestus had endowed these women with “mind (our equivalent of thinking), wits, voice, and vigor” as well as the knowledge and skill sets of the immortal gods. Mayor remarks, “they are endowed with what AI specialists term ‘augmented intelligence’ based on ‘big data’ and ‘machine learning’.” They even served as a storehouse, you might say database, of divine knowledge.[Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 22, 2019]

6th century BC Trireme

According to Homer, there was a people known as the Phaeacians who possessed ships that were steered exclusively by thought and words. King Alcinous, who permits Odysseus to use one of these ships, says that the ships merely “need to be told his city and country and they will devise the route accordingly.” As Adriene Mayor wryly notes, the ancient Greeks appear to have dreamt of something like GPS. Others were said to have created doors that moved automatically, anticipating our modern distaste for getting out of our cars with almost prophetic skill.

For those who thought about such things, robot stories provoked some conversations about ethics. In a section of the Politics dedicated to a defense of slavery, Aristotle speculated that if life could become fully automated “then craftsmen would have no need of servants and masters would have no need of slaves.” The statement is somewhat ironic: machines have freed many people from hard labor but they also threaten the ability of many others to earn money and support themselves. Aristotle was further still from the our modern sci-fi trope, in which rebellious machines attempt to enslave or destroy the human race.

Book “Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology” by Adrienne Mayor, the medical historian and classicist (2019]

Ancient Greek Advances in Textiles and Shipbuilding

The methods used to make wool and cloth in ancient Greece lived on for centuries. After a sheep was sheared, the wool was placed on a spike called a distaff. A strand of wool was then pulled off; a weight known as whorl was attached to it; and the strand was twisted into a thread by spinning with it the thumb and forefinger. Since each thread was made this way, you can how time consuming it must have been to make a piece of cloth or a sail for a ship.| [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||] To make cloth, threads were placed on a warp-weighted loom (similar to ones used by Lapp weavers until the 1950's). Warps are the downward hanging threads on a loom, and they were set up so that every other thread faced forward and the others were in the back. A weft (horizontal thread) was then taken in between the forward and backward row of warps. Before the weft was threaded through in the other direction, the position of the warps was changed with something called a heddle rod. This simple tool reversed the warps so that the row in the front was now in the rear, and visa versa. In this way the threads were woven in a cross stitch manner that held them together and created cloth. The cloth in turn was used to make cushions, upholstery for wooden furniture and wall hangings as well as garments and sails.||

On ancient Greek and Roman ships the hulls were built first and then strengthened with an internal frame. The practice of building ribs onto the keel and then attaching hull planks to the skeletons did not become commonplace until the Middle Ages. Instead planks in the hull were held together with mortises and tenons (slots and wooden pieces) that were fit together with great skill.

The mortises (slots) were drilled into the planks and spaced from five to 10 inches apart. Adjoining planks had mortise in the same places. Tenons (wooden pieces) were placed in the slots to hold the planks together. Wooden pegs or copper nails were then hammered into the tenons to hold them in place. The fit was so tight that caulking wasn’t needed. The hull was tarred and sheathed in lead primarily as protection from shipworms. The thickness of the planks varied from one inch to four inches. Hulls with thin planks had two layers of planks around the keel.

Iron and Ancient Metallurgy

iron tools Metal was worked in a shaft furnace and shaped with an anvil and hammer, The Greeks made iron stronger by quenching in cold water while the metal was still hot. The Romans learned how to temper it. The Greeks gained access to tin needed to make bronze when they colonized what is now Marseilles.

The Iron Age began around 1,500 B.C. It followed the Stone Age, Copper Age and Bronze Age. North of Alps it was from 800 to 50 B.C. Iron was used in 2000 B.C. Improved iron working from the Hittites became wide spread by 1200 B.C. Iron was made around 1500 B.C. by the Hitittes. About 1400 B.C., the Chalbyes, a subject tribe of the Hitittes invented the cementation process to make iron stronger. The iron was hammered and heated in contact with charcoal. The carbon absorbed from the charcoal made the iron harder and stronger. The smelting temperature was increased by using more sophisticated bellows.

Iron — a metal a that is not harder or stronger than bronze but keeps an edge better — proved to be an ideal material for improving weapons and armor as well as plows (land with soil previously to hard to cultivate was able to be farmed for the first time). Although it is found all over the world, iron was developed after bronze because virtually the only source of pure iron is meteorites and iron ore is much more difficult to smelt (extract the metal from rock) than copper or tin. Some scholars speculate the first iron smelts were built on hills where funnels were used to trap and intensify wind, blowing the fire so it was hot enough to melt the iron. Later bellows were introduced and modern iron making was made possible when the Chinese and later Europeans discovered how to make hotter-burning coke from coal. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Metal making secrets were carefully guarded by the Hittites and the civilizations in Turkey, Iran and Mesopotamia. Iron could not be shaped by cold hammering (like bronze), it had to be constantly reheated and hammered. The best iron has traces of nickel mixed in with it. About 1200 BC, scholars suggest, cultures other than the Hittites began to possess iron. The Assyrians began using iron weapons and armor in Mesopotamia around that time with deadly results, but the Egyptians did not utilize the metal until the later pharaohs. Lethal Celtic swords dating back to 950 BC have been found in Austria and its is believed the Greeks learned to make iron weapons from them.

Ancient Inventions

In fact, many of the inventions that we believe belong to our own modern era already existed hundreds, sometimes even thousands of years ago. Our ancestors were not quaint superstitious people mystified by the problems of everyday life; they were, much as we are today, hard at work on ingenious solutions. The authors have broken down the inventions into different categories such as medicine; food, drink and drugs; transportation and communications; and military technology, making the book easy to thumb through in the coffee-table style, rather than one to be read from start to finish.

ancient automated vending machine, AD 1st century Alexandria

We learn that our ancestors used birth control — everything from a condom to a rudimentary form of the pill — abused drugs ranging from hallucinogenic mushrooms to cocaine, and were entertained by sport, music and theater. We see homes many thousands of years old with plumbing, indoor ovens, and many other conveniences we associate with our own era.

But by far the most interesting parts of the book are those that provide examples of technology, rather than everyday objects. Inhabitants of present-day Iraq, for instance, had developed a form of electric battery about 2,000 years ago, using a clay jar that contained a copper rod sealed with asphalt. The so-called Baghdad Battery, discovered in 1936, was probably used by jewelers to electroplate bronze jewelry. Medicine, including brain surgery, the making of artificial limbs and plastic surgery, is one of the most hair-raising chapters. Early military technology, including a "machine gun" in the form of a crossbow that could fire 20 arrows in less than 15 seconds, is also covered.

The book's black-and-white photos and drawings are helpful in explaining how some of these ancient inventions worked. Many of them are taken from ancient sources, such as the sketch of a child in a high chair (or is it on a potty? the authors ask) from a Greek vase, or papyrus paintings of an Egyptian suffering from the effects of a hangover. It is a pity that there are not more of these, because they help bring the inventions to life.

Book: “Ancient Inventions”by Peter James and Nick Thorpe (Ballantine Books, 1995) is a compendium of curiosities dating from the Stone Age to 1,000 A.D., the book argues that just because our ancestors lived long ago and had less technology at their disposal does not mean they were any less intelligent than we are. [Source: Laura Colby, New York Times, May 16, 1995]

Automatons and Diving Bells in Ancient Greece

J. Wisniewski wrote in Listverse: Long before submarines and scuba suits, the ancient Greeks were devising ingenious ways to extend divers’ and explorers’ time underwater. The Greeks pioneered the use of diving bells, which were inverted kettles and barrels submerged with weights. The trapped air displaced the water and created an air pocket, allowing divers to repeatedly return to the bell to breathe without surfacing. Aristotle recorded the diving bell in use by Greek divers in 360 B.C. About 30 years later, Alexander the Great supposedly manned a similar submersible on multiple occasions. Using either a glass barrel or a barrel with a glass window, Alexander dove with the express purpose of undersea exploration. Later, Alexander used diving bells at the siege of the island city of Tyre. [Source J. Wisniewski, Listverse, July 21, 2014]

The mechanical figures and animals speaking and moving automatically in theme parks all over the world seem like they must be recent inventions. They’re not, however, because 2,000 years ago, Heron of Alexandria was entertaining Greco-Roman Egypt with an incredible array of automata. Heron was a mathematician, engineer, teacher, and all-around scientist who lived and worked in Alexandria during the first century A.D. In addition to writing at least 13 books on mathematics and physics, Heron created automatic spectacles for religious and theatrical purposes. To open and close temple doors, Heron devised a steam-based mechanism that needed only a lit brazier to operate.

As impressive as that is, it pales in comparison to Heron’s automatic theaters. Using sand as a timer to operate a system of hidden weights, Heron created a theater of miniatures that was programmed to act out an entire play. Dolphins leaped and dove, nymphs danced, ships sailed, and puppet-sized figures entered and exited the stage. And none of the movement required human intervention beyond the initial switch.Heron even staged battles between large figures of Heracles and dragons. His most impressive achievement might have been his programmable robots that used counterweight motors and carefully arranged ropes to dictate the figures’ and contraptions’ movement patterns.The scope of Heron’s inventions is enormous, and their mechanisms resist neat summary. Detailed enough records exist of his automata that modern researchers have recreated some of them successfully.

Ancient Greek Sundials and Water Clocks

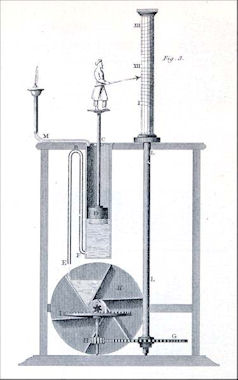

Clepsydra (water clock)

Sundials didn't measure 60 minute hours. Instead they divided the daylight into 12 hours of equal length. Greek sundials looked like inside of the bottom half of a globe. On one side was the pointer that created the shadow and on the other side were lines curving up the side of the globe. These curving lines marked off the hours and compensated for the changing of the sun's position with the seasons. The length of the hours varied from about 45 minutes in the winter time to 75 minutes in the summer. The Greeks called sundials "Hunt-the-Shadow." The Tower of the Winds in Athens had sundials on four sides, which meant an observer could tell the time at any time of the day on three sides of the tower. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

The Greeks used water clocks as the Egyptians had done since the 15th century B.C., Water clocks operate on the principle that water can be made to drip at a fairly constant rate from a bowl with a tiny hole in the bottom. Most Greek water-clocks functioned like hour glasses. They measuring about twenty minutes and were used to limit politician's speeches and the speaking time of accusers and defendants in a court of law. The huge water-clock in the Tower of the Winds not only marked off 24 hours, it showed the seasons and predicted astrological phenomena as well. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

Large water-clocks were rare. They were generally too unwieldy and messy to put in someone's home (water either had to be piped in or someone had to be willing to constantly fill a lot of empty tubs). To be calibrated properly, the flow and the pressure of water had to remain constant. What's more, the lengths of night time hours changed with the season, in opposition to the hours of the day, and this was just too complicated for the Greeks to deal with.∞

See Separate Article: TIME IN ANCIENT GREECE: CLOCKS, DIVISIONS, DAYS europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Cranes

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Structures such as the Parthenon were only made possible by the invention of the crane, which is considered to be one the Greeks’ greatest technological innovations. The device allowed heavy blocks to be lifted and set into place using relatively few men. “Lifting methods previously employed by the Greeks, as well as by other ancient cultures, required large ramps and scaffolds of earth or mudbrick,” says University of Notre Dame architectural historian Alessandro Pierattini. “Building and dismantling such massive earthworks required a large workforce.” [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2019]

It has long been thought that the crane was developed toward the end of the sixth century B.C. However, Pierattini suggests that the Greeks experimented with crane technology at least a century earlier. By reexamining ashlar blocks from the Temples of Apollo at Corinth and Poseidon at Isthmia — the oldest-known Greek temples built from stone — he determined that grooves cut into the bottom and sides of these blocks were used to secure ropes attached to a primitive lifting device. Levers could also be inserted into the blocks, which weighed as much as 850 pounds, helping to maneuver them into their final position.

Ancient Greek Magnets, Screws, Thermoscopes and Navigation Tools

Hero's mobile automaton, AD 1st century, Alexandria

According to legend Magnesia (magnet-bearing stone) was discovered by a shepherd named Magnets in ancient Thessaly along the Aegean Sea when a strange mineral pulled out all the nails out of his shoes. Loadstones made from magnetic rock were used as a medicine and a contraceptive; their magic, the Greeks believed, was powerful enough to force unfaithful wives to admit their transgressions and cure bad breath caused by garlic and onions. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

Screws were hard to make and in short supply in Greece and Rome. Most everything from furniture to ships was held together with bronze or iron nails. The ancient Greek scientist Hero may have devised a screw cutting tool, but making screws in large numbers was a difficult task. It wasn't until the invention of semi-modern lathes in the 16th century that it became possible to mass produce them.∞

Long before "thermometers" were invented, Philo of Byzantium (second century B.C.) used "thermoscopes" and "fountains that drip in the sun" based on the principal that water rose up a tube when heated.

Astrolabes — astronomical calculators used to solve problems relating to time and location based on the positions of the Sun and stars in the sky — were invented by the Greeks and improved by the Arabs. The only thing the Greek mariners needed to measure their latitudinal position was a sighting device that measured degrees above the horizon of either the sun or the north star. The north star was the easiest to measure because adjustments did not have to be made for the season like they did with the sun. The simple measuring device was made of two rods, hinged at one end. Held sideways, the bottom rod was leveled to the horizon and the upper one was pointed at the sun or star. The angle between the two rods yielded the angle of inclination of the sun or star, and with tables the latitude could be ascertained. More sophisticated astrolabes evolved from these devises. ∞

Antikythera Mechanism, the World's First Computer

The Antikythera Mechanism is the earliest known device to contain an intricate set of gear wheels. It was discovered by sponge divers on a shipwreck of a Greek cargo ship off Antikythera, a Greek island north of Crete, in 1901 but until recently no one knew what it did. Using X-ray tomography, computer models and copies of the actual pieces, scientists from Britain, Greece and the United States were able to reconstruct the device, whose sophistication was far beyond what was though possible for the ancient Greeks.

Antikythera Mechanism In November 2006, in an article published in Nature, team of researchers lead by Mike Edmunds of the University of Cardiff announced they had pieced together and figured out of the functions of the Antikythera Mechanism — an ancient astronomical calculator made at the end of the 2nd century B.C. that was so sophisticated it has been described as the world’s first analog computer. The devise was more accurate and complex than any instrument that would appear for the next 1,000 years. [Source: Reuters]

The shoe-box-size device was comprised of a maze 37 hand-cut, interlocking, bronze gear wheels packed together sort of like the gears in a watch and was housed in a wooden case with mysterious inscriptions on the face, cover and bronze dials. Originally thought to be a kind of navigational astrolabe, archaeologists continue to uncover its uses and have come to realize that at the very least is an extremely sophisticated astronomical calendar. Edmunds told Reuters, What is extraordinary is that they were able to make such a sophisticated technological device and be able to put that into metal.” Edmunds said the device is unique and nothing like as sophisticated would appear until the Middle Ages, when the first cathedral clocks were put into use.

See Separate Article: ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM — THE WORLD'S OLDEST COMPUTER europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024