When we picture ancient engineering, it is tempting to imagine brute force doing all the work: armies of laborers dragging stone, stacking bricks, and carving roads into the landscape by sheer effort. Labor mattered, but it was never enough on its own. Temples needed square corners and stable foundations. Roads needed reliable gradients and drainage. Cities needed boundaries, right angles, and repeatable measurements that could be checked, taught, and enforced. Across Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, and Rome, builders solved these problems with a toolkit that looks simple today: ropes, plumb bobs, sighting poles, water levels, and carefully trained eyes. Underneath that simplicity was something sophisticated: standardized measurement, practical geometry, and institutional systems that kept projects consistent over long distances and long periods.

Egypt: Aligning Monuments With Ropes, Plumbs, and Ritual Precision

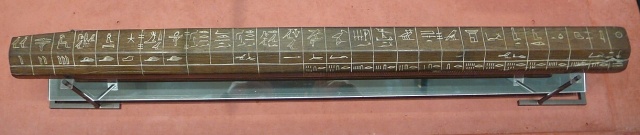

In ancient Egypt, construction and land measurement were closely linked. The Nile’s annual floods could erase field boundaries, making remeasurement essential for taxation, administration, and rebuilding. A long-standing tradition describes Egyptian surveyors as “rope stretchers,” a term reflected in later Greek usage (harpedonaptae) and in discussions of early surveying history.

The rope itself was not a casual piece of equipment. A rope with fixed intervals could be pulled taut between stakes to measure distances and lay out lines. Combined with a plumb bob, it allowed builders to establish verticals and verify alignment. Surveying, in other words, was already a systematic practice, not improvised guesswork.

Egyptian temple building also included formal “foundation” ceremonies that involved establishing axes and boundaries. While the surviving evidence spans many periods and interpretations vary, academic treatments of the “stretching of the cord” tradition emphasize that layout was a recognized and represented step in sacred construction, not an afterthought.

The key point for understanding Egyptian design is this: even without metal rulers and modern transits, builders could reliably reproduce straight lines, right angles, and consistent dimensions by combining standardized units (such as cubit measures), tensioned cords, and simple vertical references. Those methods scale. If you can repeat the same right angle at the foundation level, you can propagate it through walls, courtyards, pylons, and processional ways.

Mesopotamia: Cities, Canals, and the Administrative Side of Engineering

If Egypt illustrates measurement tied to monuments and land recovery, Mesopotamia highlights measurement tied to water and administration. Southern Mesopotamia depended heavily on irrigation, and scholarship emphasizes the deep connection between irrigation systems, early states, and organizational capacity.

In practical terms, canals and field systems require more than digging. They demand controlled gradients, coordinated maintenance, and rules for allocating water. Textual and archaeological research on Mesopotamian irrigation underscores that networks were extensive and that managing them involved structured decision-making over time.

Recent landscape research in the Eridu region, published in Antiquity, mapped and analyzed a large preserved network of artificial irrigation canals, highlighting how intensively engineered the landscape could be from the sixth to early first millennium BC. Even though specific construction techniques could vary, the presence of dense canal systems implies surveying, planning, and ongoing governance.

Mesopotamian urban form also reflects measured thinking. City walls, temple precincts, and administrative districts were not only symbolic but also functional. In canal-based agriculture, a misjudged slope or boundary dispute could mean crop failure or social conflict. The engineering challenge was therefore both technical and institutional: designing structures that worked and building systems that ensured people maintained them.

Greece: Turning Craft Knowledge Into Geometry

Greek builders inherited practical techniques common around the eastern Mediterranean, but Greek intellectual culture is often associated with formalizing and teaching the principles behind those techniques. The shift is visible in the way later writers describe geometry as foundational knowledge for design and construction. Even if builders learned on the job, the idea that built space could be explained through abstract rules became influential.

Right angles are a good example. You do not need a textbook to build a perpendicular corner, but you do need a reliable method to reproduce it consistently. Surveying history discussions note tools and practices used to establish right angles and alignments long before modern instruments.

One reason the Pythagorean tradition matters in an architectural context is that it captures a relationship builders could apply in layout, whether or not they expressed it formally. This principle later became fundamental to geometry and is still taught today as the Pythagorean theorem.

Rome: Standardization at Empire Scale

The Roman achievement was not just building big, but building repeatably across an empire. That required standards: standard widths, layers, drainage approaches, and surveying practices. Roman roads are repeatedly noted for straightness, solid foundations, cambered surfaces for drainage, and systematic construction principles.

Straightness did not happen by accident. Surveying practice in the classical world relied on sighting and simple alignment tools. Historical sources describe the groma as a right-angle device that became standard in Roman use: a cross with plumb lines that allowed surveyors to lay out perpendicular lines and grids.

Leveling was equally important, especially for aqueducts and water infrastructure where small gradient errors could ruin performance. Vitruvius, writing in the late Republic or early Empire, describes leveling methods and instruments in De architectura, including the chorobates, a device associated with checking horizontal planes.

These tools were simple, but their power came from process. Roman surveying and construction were professionalized, and Roman engineers worked with repeatable steps: clear a route, set alignments, excavate to firm ground, lay foundational courses, and build surfaces designed to shed water. The famous durability of Roman roads reflects this system mindset more than any single material.

Cities Without GPS: Grids, Boundaries, and the Logic of Repeatable Measurement

Temples, roads, and canals are dramatic, but cities show how measurement became a daily reality. Laying out a town plan involves deciding where streets meet, how blocks subdivide, how public spaces align, and how property boundaries are recorded. In many ancient contexts, those tasks were not purely “engineering” in the modern sense. They were also legal and administrative acts. A straight street is also a boundary. A marked corner is also a tax line.

This is where ancient “low-tech” tools shine. A plumb line does not wear out quickly. A rope can be remade to a standard. A sightline can be checked by multiple people. Water can serve as a leveling reference. These are robust technologies precisely because they rely on stable physical principles rather than fragile machinery. They also work in teams: one person sights, another adjusts a stake, another pulls the rope taut, another verifies the plumb.

Conclusion: Simplicity That Scales

Ancient builders did not lack sophistication. They built sophisticated systems using simple instruments because simple instruments are dependable, teachable, and scalable. Egypt shows how rope, plumb, and ceremony could align monumental architecture. Mesopotamia shows how water management demanded organized planning and long-term coordination. Greece shows how practical layout could be expressed as general principles. Rome shows how those principles, combined with standardized processes, could produce infrastructure that still shapes landscapes today.

The real lesson of building without modern tools is not that ancient people worked blindly. It is that they understood measurement deeply enough to turn ropes, gravity, and water into a design language, and then built institutions capable of applying that language across fields, cities, and empires.