PYTHAGOREANS

Pythagoreans

The Pythagoreans were followers of the philosopher-mathematician Pythagoras. Headquartered first on the island of Samos and later Croton in southern Italy, they were the first to make the profound discovery that all aspects of nature — musical notes, mathematics, science, architecture and engineering — followed rules that were determined by the relationship between numbers.

The Pythagoreans were like an ascetic religious cult. They believed in reincarnation and conducted purification rituals that attempted to erase wrongs committed in past lives. They were required to follow many rules. They had to be vegetarians. They couldn't drink wine and were required to observe periods of silence. Their purification rituals were conducted with great secrecy.

John Burnet wrote in “Early Greek Philosophy”: “The Pythagorean Order was simply, in its origin, a religious fraternity, and not, as has been maintained, a political league. Nor had it anything whatever to do with the "Dorian aristocratic ideal." Pythagoras was an Ionian, and the Order was originally confined to Achaean states. Moreover the "Dorian aristocratic ideal" is a fiction based on the Socratic idealization of Sparta and Crete. Corinth, Argos, and Syracuse are quite forgotten. Nor is there any evidence that the Pythagoreans favored the aristocratic party. The main purpose of the Order was the cultivation of holiness. In this respect it resembled an Orphic society, though Apollo, and not Dionysus, was the chief Pythagorean god. That is doubtless due to the connection of Pythagoras with Delos, and explains why the Crotoniates identified him with Apollo Hyperboreus. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

See Separate Articles:

PYTHAGORAS: LIFE, LEGENDS AND ODDITIES europe.factsanddetails.com

PYTHAGOREANS, MATH, MUSIC AND GEOMETRY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK PHILOSOPHY AND PHILOSOPHERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY GREEK PHILOSOPHY, COSMOLOGY AND SCIENCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY ANCIENT GREEK PHILOSOPHER-SCIENTISTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ELEATIC SCHOOL OF PHILOSOPHY: PARMENIDES, XENOPHANES, ZENO AND MELISSUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library: An Anthology of Ancient Writings Which Relate to Pythagoras and Pythagorean Philosophy” by Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie and David Fideler (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Harmony of the Spheres: The Pythagorean Tradition in Music” by Joscelyn Godwin | (1992) Amazon.com;

“Pythagoras: His Life and Teachings” by Thomas Stanley, James Wasserman, J. Daniel Gunther (2010) Amazon.com;

“Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans” by Charles H. Kahn (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Pythagoreans: Digest (Rosicrucian Order) by Rosicrucian Order AMORC, Peter Kingsley, Ruth Phelps Amazon.com;

“The Manual of Harmonics of Nicomachus the Pythagorean” by Nicomachus of Gerasa and Flora R. Levin (1993) Amazon.com;

“On the Pythagorean Way of Life [Iamblichus]: Text, Translations, and Notes (English, Ancient Greek) by Iamblicus, John M. Dillon (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition”

by Peter Kingsley (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Metaphysics of the Pythagorean Theorem: Thales, Pythagoras, Engineering, Diagrams, and the Construction of the Cosmos out of Right Triangles” by Robert Hahn (2018) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Music” by M. L. West (1994)

Amazon.com;

“Music in Ancient Greece: Melody, Rhythm and Life” (Classical World)

by Spencer A. Klavan (2021) Amazon.com;

“Mode in Ancient Greek Music” (Cambridge Classical Studies)

by R. P. Winnington-Ingram (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Science” by Liba Taub (2020) Amazon.com;

“Sourcebook in the Mathematics of Ancient Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean”

by Victor J. Katz and Clemency Montelle (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World” by Charles Freeman (2000) Amazon.com;

“Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle” by G. E. R. Lloyd (1974) Amazon.com;

Rise, Fall and Survival of the Pythagorean Order

“For a time the new Order succeeded in securing supreme power in the Achaean cities, but reaction soon came. Our accounts of these events are much confused by failure to distinguish between the revolt of Cylon in the lifetime of Pythagoras himself, and the later risings which led to the expulsion of the Pythagoreans from Italy. It is only if we keep these apart that we begin to see our way. Timaeus appears to have connected the rising of Cylon closely with the events which led to the destruction of Sybaris (510 B.C.). [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

“We gather that in some way Pythagoras had shown sympathy with the Sybarites, and had urged the people of Croton to receive certain refugees who had been expelled by the tyrant Telys. There is no ground for the assertion that he sympathized with these refugees because they were "aristocrats"; they were victims of a tyrant and suppliants, and it is not hard to understand that the Ionian Pythagoras should have felt a certain kindness for the men of the great but unfortunate Ionian city. Cylon, who is expressly stated by Aristoxenus to have been one of the first men of Croton in wealth and birth, was able to bring about the retirement of Pythagoras to Metapontum, another Achaean city, and it was there that he passed his remaining years.

“Disturbances still went on, however, at Croton after the departure of Pythagoras for Metapontum and after his death. At last, we are told, the Cyloneans set fire to the house of the athlete Milo, where the Pythagoreans were assembled. Of those in the house only two, who were young and strong, Archippus and Lysis, escaped. Archippus retired to Taras, a democratic Dorian state: Lysis, first to Achaea and afterwards to Thebes, where he was later the teacher of Epaminondas. It is impossible to date these events accurately, but the mention of Lysis proves that they were spread over more than one generation. The coup d'Etat of Croton can hardly have occurred before 450 B.C., if the teacher of Epaminondas escaped from it, nor can it have been much later or we should have heard of it in connection with the foundation of Thourioi in 444 B.C. In a valuable passage, doubtless derived from Timaeus, Polybius tells us of the burning of the Pythagorean "lodges" (sunedria) in all the Achaean cities, and the way in which he speaks suggests that this went on for a considerable time, till at last peace and order were restored by the Achaeans of Peloponnesus. We shall see that at a later date some of the Pythagoreans were able to return to Italy, and once more acquired great influence there.”

“After losing their supremacy in the Achaean cities, the Pythagoreans concentrated themselves at Rhegion; but the school founded there did not maintain itself for long, and only Archytas stayed behind in Italy. Philolaus and Lysis, the latter of whom had escaped as a young man from the massacre of Croton, had already found their way to Thebes. We know from Plato that Philolaus was there towards the close of the fifth century, and Lysis was afterwards the teacher of Epaminondas. Some of the Pythagoreans, however, were able to return to Italy later. Philolaus certainly did so, and Plato implies that he had left Thebes some time before 399 B.C., the year Socrates was put to death. In the fourth century, the chief seat of the school is the Dorian city of Taras, and we find the Pythagoreans heading the opposition to Dionysius of Syracuse. It is to this period that the activity of Archytas belongs. He was the friend of Plato, and almost realized the ideal of the philosopher king. He ruled Taras for years, and Aristoxenus tells us that he was never defeated in the field of battle. He was also the inventor of mathematical mechanics. At the same time, Pythagoreanism had taken root in the East. Lysis remained at Thebes, where Simmias and Cebes had heard Philolaus, while the remnant of the Pythagorean school of Rhegion settled at Phlius.

Pythagorean Belief on the Transmigration of the Soul

The Pythagoreans believed in immortality and “transmigration of the soul” (the idea that after death souls went to heaven or occupied the bodies of men or animals). They also thought that pure knowledge was the essence of the soul and the best means of attaining pure knowledge was through numbers.

Pythagoras reportedly taught the doctrine of transmigration. Some scholars say this belief is most easily to be explained as a development of the view in the kinship of men and beasts, a view which Dicaearchus said Pythagoras held. Further, this belief is commonly associated with a system of taboos on certain kinds of food, and the Pythagorean rule is best known for its prescription of similar forms of abstinence. It seems certain that Pythagoras brought this with him from Ionia. Timaeus told how at Delos he refused to sacrifice on any but the oldest altar, that of Apollo the Father, where only bloodless sacrifices were allowed. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

Pythagoras emerging from the Underworld

Diogenes Laertius (A.D. 180-240) wrote: "On the subject of reincarnation Xenophanes bears witness in an elegy which begins "Now I will turn to another tale and show the way'. What he says about Pythagoras runs thus: Once they say that he was passing by when a puppy was being whipped, and he took pity and said, "Stop, do not beat it. For it is the soul of a friend that I recognized when I heard it giving tongue.'" [Source: Diogenes Laertius, 8. 36)

Herodotus ( c. 484–c. 425 B.C.) wrote in Histories II. 123: "Moreover the Egyptians are the first to have maintained the doctrine that the soul of man is immortal, and that when the body perishes, it enters into another animal that is being born at the time, and when it has been the complete round of the creatures of the dry land and of the sea and of the air it enters again into the body of a man at birth. And its cycle is completed in 3000 years. There are some Greeks who have adopted this doctrine, some in former times, and some in later ones, as if it were their own invention. Their names I know, but refrain from writing down."

Porphyrius wrote in the Life of Pythagoras 19: "None the less, the following became universally known: first, that he maintains that the soul is immortal; second, that it changes into other kinds of living things; third, that events recur in certain cycles and that nothing is ever absolutely new; and fourth, that all living things sould be regarded as akin. Pythagoras seems to have been the first to bring these beliefs into Greece."

Akousmata: Pythagorean Rules

The Pythagoreans believed in a general prohibition against eating animals on the grounds of “having a right to live in common with mankind." Their ideas were an inspiration for the Neoplatonist of the A.D. third and forth centuries and their views on purification of the soul before the afterlife influenced early Christians.

There are two views on Pythagorean rules, each coming from “different sources. Some of them, derived from Aristoxenus, and for the most part preserved by Iamblichus, are mere precepts of morality. They do not pretend to go back to Pythagoras himself; they are only the sayings which the last generation of "Mathematicians" heard from their predecessors. The second class is of a different nature, and consists of rules called Akousmata, which points to their being the property of the sect which had faithfully preserved the old customs. Later writers interpret them as "symbols" of moral truth; but it does not require a practiced eye to see that they are genuine taboos. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

Do not eat beans

“I give a few examples to show what the Pythagorean rule was really like.

1. To abstain from beans.

2. Not to pick up what has fallen.

3. Not to touch a white cock.

4. Not to break bread.

5. Not to step over a crossbar.

6. Not to stir the fire with iron.

7. Not to eat from a whole loaf.

8. Not to pluck a garland.

9. Not to sit on a quart measure.

10. Not to eat the heart.

11. Not to walk on highways.

12. Not to let swallows share one's roof.

13. When the pot is taken off the fire, not to leave the mark of it in the ashes, but to stir them together.

14. Do not look in a mirror beside a light.

15. When you rise from the bedclothes, roll them together and smooth out the impress of the body.

Herodotus ( c. 484–c. 425 B.C.) wrote in Histories II. 81: "But woolen articles are never taken into temples, nor are (the Egyptians) buried with them. That is not lawful. They agree in this with the so-called Orphic and Bacchic practices (which are really Egyptian) and with the Pythagoreans. For it is not lawful for one who partakes in these rites to be buried in woolen clothes. There is a sacred account given on this subject."

Diogenes Laertius (A.D. 180-240) wrote: "Above all else (Pythagoras) forbade the eating of red mullet and black-tail. And he required abstinence from the heart and from beans. Also (according to Aristotle), on certain occasions, from the womb and from mullet.... He sacrificed only inanimate things. But others say that he used only cocks and suckling kids and piglets, and never lambs." [Source: Diogenes Laertius 8. 19]

“It has indeed been doubted whether we can accept what we are told by such late writers as Porphyry on the subject of Pythagorean abstinence. Aristoxenus undoubtedly said Pythagoras did not abstain from animal flesh in general, but only from that of the ploughing ox and the ram. He also said that Pythagoras preferred beans to every other vegetable, as being the most laxative, and that he was partial to sucking-pigs and tender kids. The palpable exaggeration of these statements shows, however, that he is endeavoring to combat a belief which existed in his own day, so we can show, out of his own mouth, that the tradition which made the Pythagoreans abstain from animal flesh and beans goes back to a time long before the Neopythagoreans. The explanation is that Aristoxenus had been the friend of the last of the Pythagoreans; and, in their time, the strict observance had been relaxed, except by some zealots whom the heads of the Society refused to acknowledge. The "Pythagorists" who clung to the old practices were now regarded as heretics, and it was said that the Akousmatics, as they were called, were really followers of Hippasus, who had been excommunicated for revealing secret doctrines. The genuine followers of Pythagoras were the Mathematicians. The satire of the poets of the Middle Comedy proves, however, that, even though the friends of Aristoxenus did not practice abstinence, there were plenty of people in the fourth century, calling themselves followers of Pythagoras, who did. We know also from Isocrates that they still observed the rule of silence. History has not been kind to the Akousmatics, but they never wholly died out. The names of Diodorus of Aspendus and Nigidius Figulus help to bridge the gulf between them and Apollonius of Tyana.

“We have seen that Pythagoras taught the kinship of beasts and men, and we infer that his rule of abstinence from flesh was based, not on humanitarian or ascetic grounds, but on taboo. This is strikingly confirmed by a statement in Porphyry's Defence of Abstinence, to the effect that, though the Pythagoreans did as a rule abstain from flesh, they nevertheless ate it when they sacrificed to the gods. Now, among primitive peoples, we often find that the sacred animal is slain and eaten on certain solemn occasions, though in ordinary circumstances this would be the greatest of all impieties. Here, again, we have a primitive belief; and we need not attach any weight to the denials of Aristoxenus.

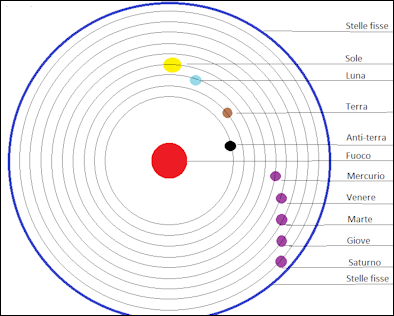

Pythagorean Cosmology

Pythagorean view of the universe

The Pythagoreans believed the world was a sphere and that the sphere was the most perfect shape. They then took that idea a step further, theorizing that the Earth was the center of the universe because all objects are pulled to the center of something, which creates a sphere (in this case the Earth).

“Now the most striking statement of this kind is one of Aristotle's. The Pythagoreans held, he tells us, that there was "boundless breath" outside the heavens, and that it was inhaled by the world. In substance, that is the doctrine of Anaximenes, and it becomes practically certain that it was taught by Pythagoras, when we find that Xenophanes denied it. We may infer that the further development of the idea is also due to Pythagoras. We are told that, after the first unit had been formed — however that may have taken place — the nearest part of the Boundless was first drawn in and limited; and that it is the Boundless thus inhaled that keeps the units separate from each other. It represents the interval between them. This is a primitive way of describing discrete quantity.

“In these passages of Aristotle, the "breath" is also spoken of as the void or empty. This is a confusion we have already met with in Anaximenes, and it need not surprise us to find it here. We find also clear traces of the other confusion, that of air and vapor. It seems certain, in fact, that Pythagoras identified the Limit with fire, and the Boundless with darkness. We are told by Aristotle that Hippasus made Fire the first principle, and we shall see that Parmenides, in discussing the opinions of his contemporaries, attributes to them the view that there were two primary "forms," Fire and Night. We also find that Light and Darkness appear in the Pythagorean table of opposites under the heads of the Limit and the Unlimited respectively. The identification of breath with darkness here implied is a strong proof of the primitive character of the doctrine; for in the sixth century darkness was supposed to be a sort of vapor, while in the fifth its true nature was known. Plato, with his usual historical tact, makes the Pythagorean Timaeus describe mist and darkness as condensed air. We must think, then, of a "field" of darkness or breath marked out by luminous units, an imagination the starry heavens would naturally suggest. It is even probable that we should ascribe to Pythagoras the Milesian view of a plurality of worlds, though it would not have been natural for him to speak of an infinite number. We know, at least, that Petron, one of the early Pythagoreans, said there were just a hundred and eighty-three worlds arranged in a triangle.

“Anaximander had regarded the heavenly bodies as wheels of "air" filled with fire which escapes through certain orifices (§ 21), and there is evidence that Pythagoras adopted the same view. We have seen that Anaximander only assumed the existence of three such wheels, and it is extremely probable that Pythagoras identified the intervals between these with the three musical intervals he had discovered, the fourth, the fifth, and the octave. That would be the most natural beginning for the doctrine of the "harmony of the spheres," though the expression would be doubly misleading if applied to any theory we can properly ascribe to Pythagoras himself. The word harmonia does not mean harmony, but octave, and the "spheres" are an anachronism. We are still at the stage when wheels or rings were considered sufficient to account for the heavenly bodies.

“The distinction between the diurnal revolution of the heavens from east to west, and the slower revolutions of the sun, moon, and planets from west to east, may also be referred to the early days of the school, and probably to Pythagoras himself. It obviously involves a complete break with the theory of a vortex, and suggests that the heavens are spherical. That, however, was the only way to get out of the difficulties of Anaximander's system. If it is to be taken seriously, we must suppose that the motions of the sun, moon, and planets are composite. On the one hand, they have their own revolutions with varying angular velocities from west to east, but they are also carried along by the diurnal revolution from east to west. Apparently this was expressed by saying that the motions of the planetary orbits, which are oblique to the celestial equator, are mastered (krateitai) by the diurnal revolution. The Ionians, down to the time of Democritus, never accepted this view. They clung to the theory of the vortex, which made it necessary to hold that all the heavenly bodies revolved in the same direction, so that those which, on the Pythagorean system, have the greatest angular velocity have the least on theirs. On the Pythagorean view, Saturn, for instance, takes about thirty years to complete its revolution; on the Ionian view it is "left behind" far less than any other planet, that is, it more nearly keeps pace with the signs of the Zodiac.

“For reasons which will appear later, we may confidently attribute to Pythagoras himself the discovery of the sphericity of the earth, which the Ionians, even Anaxagoras and Democritus, refused to accept. It is probable, however, that he still adhered to the geocentric system, and that the discovery that the earth was a planet belongs to a later generation (§ 150).

“The account just given of the views of Pythagoras is, no doubt, conjectural and incomplete. We have simply assigned to him those portions of the Pythagorean system which appear to be the oldest, and it has not even been possible at this stage to cite fully the evidence on which our discussion is based. It will only appear in its true light when we have examined the second part of the poem of Parmenides and the system of the later Pythagoreans. It is clear at any rate that the great contribution of Pythagoras to science was his discovery that the concordant intervals could be expressed by simple numerical ratios. In principle, at least, that suggests an entirely new view of the relation between the traditional "opposites." If a perfect attunement (harmonia) of the high and the low can be attained by observing these ratios, it is clear that other opposites may be similarly harmonized. The hot and the cold, the wet and the dry, may be united in a just blend (krasis), an idea to which our word "temperature" still bears witness. The medical doctrine of the "temperaments" is derived from the same source. Moreover, the famous doctrine of the Mean is only an application of the same idea to the problem of conduct. It is not too much to say that Greek philosophy was henceforward to be dominated by the notion of the perfectly tuned string.

Central Fire

“The planetary system which Aristotle attributes to "the Pythagoreans" and Aetius to Philolaus is sufficiently remarkable. The earth is no longer in the middle of the world; its place is taken by a central fire, which is not to be identified with the sun. Round this fire revolve ten bodies. First comes the Antichthon or Counter-earth, and next the earth, which thus becomes one of the planets. After the earth comes the moon, then the sun, the planets, and the heaven of the fixed stars. We do not see the central fire and the antickthon because the side of the earth on which we live is always turned away from them. This is to be explained by the analogy of the moon, which always presents the same face to us, so that men living on the other side of it would never see the earth. This implies, of course, from our point of view, that these bodies rotate on their axes in the same time as they revolve round the central fire, and that the antichthon revolves round the central fire in the same time as the earth, so that it is always in opposition to it.

“It is not easy to accept the statement of Aetius that this system was taught by Philolaus. Aristotle nowhere mentions him in connection with it, and in the Phaedo Socrates gives a description of the earth and its position in the world which is entirely opposed to it, but is accepted without demur by Simmias the disciple of Philolaus. It is undoubtedly a Pythagorean theory, however, and marks a noticeable advance on the Ionian views current at Athens. It is clear too that Socrates states it as something of a novelty that the earth does not require the support of air or anything of the sort to keep it in its place. Even Anaxagoras had not been able to shake himself free of that idea, and Democritus still held it along with the theory of a flat earth. The natural inference from the Phaedo would certainly be that the theory of a spherical earth, kept in the middle of the world by its equilibrium, was that of Philolaus himself. If so, the doctrine of the central fire would belong to a later generation.

“It seems probable that the theory of the earth's revolution round the central fire really originated in the account of the sun's light given by Empedocles. The two things are brought into close connection by Aetius, who says that Empedocles believed in two suns, while "Philolaus" believed in two or even in three. His words are obscure, but they seem to justify us in holding that Theophrastus regarded the theories as akin. We saw that Empedocles gave two inconsistent explanations of the alternation of day and night, (§ 113) and it may well have seemed that the solution of the difficulty was to make the sun shine by reflected light from a central fire. Such a theory would, in fact, be the natural issue of recent discoveries as to the moon's light and the cause of its eclipses, if these were extended to the sun, as they would almost inevitably be.

“The central fire received a number of mythological names, such as the "hearth of the world," the "house," or "watch-tower" of Zeus, and "the mother of the gods." That was in the manner of the school, but it must not blind us to the fact that we are dealing with a scientific hypothesis. It was a great thing to see that the phenomena could best be "saved" by a central luminary, and that the earth must therefore be a revolving sphere like the other planets. Indeed, we are tempted to say that the identification of the central fire with the sun was a detail in comparison. It is probable, at any rate, that this theory started the train of thought which made it possible for Aristarchus of Samos to reach the heliocentric hypothesis, and it was certainly Aristotle's successful reassertion of the geocentric theory which made it necessary for Copernicus to discover the truth afresh. We have his own word for it that he started from what he had read about the Pythagoreans.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024