DISCOVERY OF HOMO NALEDI

Homo naledi skull

In 2015, scientists announced the discovery of a new Homo species from South Africa, named Homo naledi. Regarded as one of the most primitive Homo species yet unearthed, as its brain was only about the size of an orange, it possessed an unusual mix of human-like and non-human-like features such as a human-like skull, slender legs and feet suited for a life on the ground but shoulders, hands and curved fingers adapted for a life in the trees. Homo naledi lived between 335,000 and 236,000 years ago, about the same time that modern humans first appeared.[Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, September 10, 2015 ||]

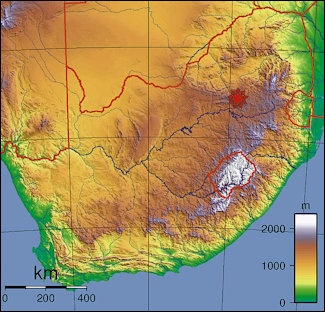

Two recreational cavers, Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker, discovered the new fossils in 2013 in a cave known as Rising Star, located in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site northwest of Johannesburg in South Africa. The species is named after the cave; "naledi" means "star" in Sesotho, a South African language. Jamie Shreeve wrote in National Geographic: In 2013, “Rising Star has been a popular draw for cavers since the 1960s, and its filigree of channels and caverns is well mapped. Steven Tucker and Rick Hunter were hoping to find some less trodden passage. In the back of their minds was another mission. In the first half of the 20th century, this region of South Africa produced so many fossils of our early ancestors that it later became known as the Cradle of Humankind. Though the heyday of fossil hunting there was long past, the cavers knew that a scientist in Johannesburg was looking for bones. The odds of happening upon something were remote. But you never know. [Source: Jamie Shreeve, National Geographic, September 2015 /+]

“Deep in the cave, Tucker and Hunter worked their way through a constriction called Superman’s Crawl—because most people can fit through only by holding one arm tightly against the body and extending the other above the head, like the Man of Steel in flight. Crossing a large chamber, they climbed a jagged wall of rock called the Dragon’s Back. At the top they found themselves in a pretty little cavity decorated with stalactites. Hunter got out his video camera, and to remove himself from the frame, Tucker eased himself into a fissure in the cave floor. His foot found a finger of rock, then another below it, then—empty space. Dropping down, he found himself in a narrow, vertical chute, in some places less than eight inches wide. He called to Hunter to follow him. Both men have hyper-slender frames, all bone and wiry muscle. Had their torsos been just a little bigger, they would not have fit in the chute, and what is arguably the most astonishing human fossil discovery in half a century—and undoubtedly the most perplexing—would not have occurred. /+\

“After contorting themselves 40 feet down the narrow chute in the Rising Star cave, Tucker and Rick Hunter had dropped into another pretty chamber, with a cascade of white flowstones in one corner. A passageway led into a larger cavity, about 30 feet long and only a few feet wide, its walls and ceiling a bewilderment of calcite gnarls and jutting flowstone fingers. But it was what was on the floor that drew the two men’s attention. There were bones everywhere. The cavers first thought they must be modern. They weren’t stone heavy, like most fossils, nor were they encased in stone—they were just lying about on the surface, as if someone had tossed them in. They noticed a piece of a lower jaw, with teeth intact; it looked human.

The bones were found in a chamber named Dinaledi (chamber of stars), accessible only through a narrow chute, almost a hundred yards from the cave entrance. How they got there is a mystery. The most plausible answer so far: Bodies were dropped in from above. Hundreds of fossils have been recovered, most excavated from a pit a mere yard square. More fossils surely await./+\

“Berger could see from the photos that the bones did not belong to a modern human being. Certain features, especially those of the jawbone and teeth, were far too primitive. The photos showed more bones waiting to be found; Berger could make out the outline of a partly buried cranium. It seemed likely that the remains represented much of a complete skeleton. He was dumbfounded. In the early hominin fossil record, the number of mostly complete skeletons, including his two from Malapa, could be counted on one hand. And now this. But what was this? How old was it? And how did it get into that cave?/+\

See Separate Article: HOMO NALEDI: CHARACTERISTICS, DEATH RITUALS, INSIGHTS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Cave of Bones” by Lee Berger (2023) Amazon.com;

“Almost Human: The Astonishing Tale of Homo Naledi and the Discovery That Changed Our Human Story” by Lee Berger, John Hawks, et al. Amazon.com;

“A Handbook to the Cradle of Humankind” by Marina C. Elliott and Lee R. Berger Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

Why Did Homo Naledi Go Into Rising the Super-Cramped Star Cave System

Stephanie Pappas wrote in Live Science: Deep within South Africa's Rising Star cave system, in a dark passageway barely 6 inches (15 centimeters) wide, scientists have discovered the remains of Homo naledi . Fossil fragments belonging to about 24 Homo naledi individuals have been found in the cave system since 2013, when the first fossils from this human ancestor were discovered in what's now known as the Dinaledi Chamber. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, November 5, 2021]

The presence of so many individuals from a single species in the cave is mysterious. The only way in is a 39-foot (12 meters) vertical fracture known as "The Chute," and geologists and spelunkers have so far found no evidence of alternative entrances into the passageways. A small Homo naledi skull was found scattered in pieces on a limestone shelf about 80 centimeters (2.6 feet) above the cave floor. The spot sits in "a spiderweb of cramped passages," Maropeng Ramalepa, a member of the exploration team, said in a statement.

The area is barely navigable for experienced spelunkers with modern equipment, according to a paper published November 4, 2021 in the journal PaleoAnthropology. There is no evidence that animals carried the H. naledi bones into the cave — there are no gnaw marks or evidence of predation. The bones also appear to have been placed in the cave, not washed in, as they were not found mixed with sediment or other debris. That leaves open the possibility that more than 240,000 years ago, human ancestors with orange-size brains deliberately entered a dark, maze-like cave, perhaps through a vertical chute that narrows to 7 inches (18 cm) in places, and placed their dead inside.

This human ancestor lived at the same time as early Homo sapiens, John Hawks, an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies the remains, told Live Science in 2017. Their apparent forays into the cave suggest that they were among modern humans' smarter ancestors, and that they had mastered the use of fire to light their explorations, Hawks said.

Recovery of the Homo Naledi Fossils

Cradle of Humankind

Alyson Krueger wrote in The Guardian: “The remains were uncovered in November 2013 during a three-week expedition, called Rising Star after the local cave system. The chamber where the remains were found is 30 metres below ground, and access is via gaps so small that team members had to extend one arm in front of their bodies, superman-style, to get through. For this reason, the six-strong group was composed of small, slim women, who earned the nickname the underground astronauts.If they had slipped while climbing down the rocks, they could have dropped 20 metres to their deaths. The expedition was so dangerous that a medical team was on hand, with doctors trained to go underground to treat any broken bones. The results were 1,550 bones unearthed, from 15 individuals, more than all previous Africa expeditions combined. [Source: Alyson Krueger, The Guardian, May 25, 2017]

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: “The fossils were recovered in two missions in 2013 and 2014 dubbed the Rising Star Expeditions. The bones lay in a chamber now named Dinaledi, meaning "many stars," located about 300 feet (90 meters) from the entrance of Rising Star. Getting into Dinaledi required a steep climb up a sharp limestone block called "the Dragon's Back" and then down a narrow crack only 7 inches (18 centimeters) wide. A global call for researchers who could fit through this chute resulted in six women chosen to serve as what the researchers called "underground astronauts." "They risked their lives on a daily basis to recover these extraordinary fossils," study lead author Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, told Live Science. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, September 10, 2015 ||]

“The scientists recovered more than 1,550 bones and bone fragments, a small fraction of the fossils believed to remain in the chamber. These represent at least 15 different individuals, including infant, child, adult and elderly specimens. This is the single largest fossil hominin find made yet in Africa. (Hominins include the human lineage and its relatives dating from after the split from the chimpanzee lineage.) "With almost every bone in the body represented multiple times, Homo naledi is already practically the best-known fossil member of our lineage," Berger said. "We will be trying to extract DNA from these fossils," Berger added.” ||

Skinny Individuals Wanted

After Berger the importance of the discovery in Rising Star, he had to figure out how to excavate and retrieve the fossils. Jamie Shreeve wrote in National Geographic: “Most pressing of all: how to get it out again, and quickly, before some other amateurs found their way into that chamber. (It was clear from the arrangement of the bones that someone had already been there, perhaps decades before.) Tucker and Hunter lacked the skills needed to excavate the fossils, and no scientist Berger knew—certainly not himself—had the physique to squeeze through that chute. So Berger put the word out on Facebook: Skinny individuals wanted, with scientific credentials and caving experience; must be “willing to work in cramped quarters.” Within a week and a half he’d heard from nearly 60 applicants. He chose the six most qualified; all were young women. Berger called them his “underground astronauts.” [Source: Jamie Shreeve, National Geographic, September 2015 /+]

“With funding from National Geographic (Berger is also a National Geographic explorer-in-residence), he gathered some 60 scientists and set up

Lee Berger

an aboveground command center, a science tent, and a small village of sleeping and support tents. Local cavers helped thread two miles of communication and power cables down into the fossil chamber. Whatever was happening there could now be viewed with cameras by Berger and his team in the command center. Marina Elliott, then a graduate student at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, was the first scientist down the chute. “Looking down into it, I wasn’t sure I’d be OK,” Elliott recalled. “It was like looking into a shark’s mouth. There were fingers and tongues and teeth of rock.”/+\

“Elliott and two colleagues, Becca Peixotto and Hannah Morris, inched their way to the “landing zone” at the bottom, then crouched into the fossil chamber. Working in two-hour shifts with another three-woman crew, they plotted and bagged more than 400 fossils on the surface, then started carefully removing soil around the half-buried skull. There were other bones beneath and around it, densely packed. Over the next several days, while the women probed a square-yard patch around the skull, the other scientists huddled around the video feed in the command center above in a state of near-constant excitement. Berger, dressed in field khakis and a Rising Star Expedition cap, would occasionally repair to the science tent to puzzle over the accumulating bones—until a collective howl of astonishment from the command center brought him rushing back to witness another discovery. It was a glorious time./+\

“The bones were superbly preserved, and from the duplication of body parts, it soon became clear that there was not one skeleton in the cave, but two, then three, then five ... then so many it was hard to keep a clear count. Berger had allotted three weeks for the excavation. By the end of that time, the excavators had removed some 1,200 bones, more than from any other human ancestor site in Africa—and they still hadn’t exhausted the material in just the one square yard around the skull. It took another several days digging in March 2014 before its sediments ran dry, about six inches down./+\

“There were some 1,550 specimens in all, representing at least 15 individuals. Skulls. Jaws. Ribs. Dozens of teeth. A nearly complete foot. A hand, virtually every bone intact, arranged as in life. Minuscule bones of the inner ear. Elderly adults. Juveniles. Infants, identified by their thimble-size vertebrae. Parts of the skeletons looked astonishingly modern. But others were just as astonishingly primitive—in some cases, even more apelike than the australopithecines. “We’ve found a most remarkable creature,” Berger said. His grin went nearly to his ears.” /+\

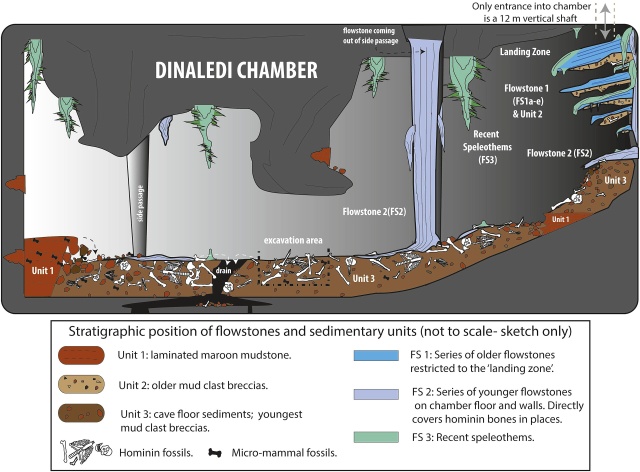

Archaeological Work at the Rising Star Cave System

Berger and his team originally thought H. naledi could only have accessed the Dinaledi chamber through a single vertical channel they dubbed the Chute. In 2014 they found the Chute was actually a network of cramped routes into the chamber. They also explored new areas where they discovered more remains, including a child’s skull. [Source: Lee Berger, National Geographic, June 5, 2023]

Lee Berger wrote in National Geographic: Rising Star cave system, which comprises nearly two and a half miles of interlaced passages, descending in some places more than 130 feet underground. Occasionally, you might find a chamber in which you can sit up or even stand. But most of the open spaces are relatively small. Marina and Becca, our two most experienced excavators, were at work in one such space, Dinaledi. As I gestured at the ghostly image on the computer screen, I looked over at Keneiloe Molopyane, an archaeologist and forensic scientist known on our team as Bones. We were watching a live stream of two colleagues, archaeologists Marina Elliott and Becca Peixotto, digging around a hundred feet beneath us. Bones leaned in to look at the screen as the light from the excavators’ head lamps darted around the chamber. “Why stop?” she asked. [Source: Lee Berger, National Geographic, June 5, 2023]

It was November 2018, and we were sitting at our team’s “command center”. Sediments in these caves formed through dust and debris slowly coming off the walls and blanketing the floor in nearly invisible layers. But the sediment that Marina and Becca were scooping out didn’t have that same level of uniformity. It appeared as if it had been disturbed. “It looks like there was a hole in the floor of the cave,” I told Bones. “I don’t think it’s a natural depression. It looks a lot like a burial feature to me,” I concluded. Bones’s eyes widened: “It does.” She considered the on-screen image again. “I think you’re making the right decision,” she said. “We should stop.” I didn’t know it then, but that decision would lead to a scientific revelation—and some of the most terrifying, and most wondrous, moments of my life.

In all the breakthroughs at Rising Star, fewer than 50 of my co-workers had shimmied down Dinaledi’s Chute, a 39-foot-long vertical passage. Its narrowest part was just seven and a half inches across. I myself had told thousands of people about the perils of this space over the years. Our previous work at Dinaledi, in 2013 and 2014, was astonishing. In less than two months’ time, my team had recovered more than 1,200 fossils—primarily bones and teeth—from a spot within Rising Star no bigger than 10 square feet.

The biggest find from our excavations in 2013 and 2014 was a skull of H. naledi that sat within a complicated array of bones and bone fragments: leg bones, arm bones, pieces of hands and feet. We named this tangle the Puzzle Box. Excavating it felt like a high-stakes version of pick-up sticks, in which each piece had to be carefully extracted without disrupting the others. In total the Puzzle Box grew to an area of about a yard across and was packed with fossil remains. We had returned to the Puzzle Box in November 2018 to test whether Dinaledi had a continuous layer of bones. We dug two new excavation squares: one south of the Puzzle Box and one north of it. The northern square revealed a concentration of fragments that looked as if they’d come from one individual. Further digging revealed a sterile area of no bones, and then another concentration of bones containing a jaw and limb bones in disarray, preserved at all angles.

Analyzing Homo Naledi

Jamie Shreeve wrote in National Geographic: “In paleoanthropology, specimens are traditionally held close to the vest until they can be carefully analyzed and the results published, with full access to them granted only to the discoverer’s closest collaborators. By this protocol, answering the central mystery of the Rising Star find—What is it?—could take years, even decades. Berger wanted the work done and published by the end of the year. In his view everyone in the field should have access to important new information as quickly as possible. And maybe he liked the idea of announcing his find, which might be a new candidate for earliest Homo, in 2014— exactly 50 years after Louis Leakey published his discovery of the reigning first member of our genus, Homo habilis. [Source: Jamie Shreeve, National Geographic, September 2015 /+]

“In any case there was only one way to get the analysis done quickly: Put a lot of eyes on the bones. Along with the 20-odd senior scientists who had helped him evaluate the Malapa skeletons, Berger invited more than 30 young scientists, some with the ink still wet on their Ph.D.’s, to Johannesburg from some 15 countries, for a blitzkrieg fossil fest lasting six weeks. To some older scientists who weren’t involved, putting young people on the front line just to rush the papers into print seemed rash. But for the young people in question, it was “a paleofantasy come true,” said Lucas Delezene, a newly appointed professor at the University of Arkansas. “In grad school you dream of a pile of fossils no one has seen before, and you get to figure it out.”/+\

“The workshop took place in a newly constructed vault at Wits, a windowless room lined with glass-paneled shelves bearing fossils and casts. The analytical teams were divided by body part. The cranial specialists huddled in one corner around a large square table that was covered with skull and jaw fragments and the casts of other well-known fossil skulls. Smaller tables were devoted to hands, feet, long bones, and so on. The air was cool, the atmosphere hushed. Young scientists fiddled with bones and calipers. Berger and his close advisers circulated among them, conferring in low voices./+\

“Delezene’s own fossil pile contained 190 teeth—a critical part of any analysis, since teeth alone are often enough to identify a species. But these teeth weren’t like anything the scientists in the “tooth booth” had ever seen. Some features were astonishingly humanlike—the molar crowns were small, for instance, with five cusps like ours. But the premolar roots were weirdly primitive. “We’re not sure what to make of these,” Delezene said. “It’s crazy.”/+\

“The same schizoid pattern was popping up at the other tables. A fully modern hand sported wackily curved fingers, fit for a creature climbing trees. The shoulders were apish too, and the widely flaring blades of the pelvis were as primitive as Lucy’s—but the bottom of the same pelvis looked like a modern human’s. The leg bones started out shaped like an australopithecine’s but gathered modernity as they descended toward the ground. The feet were virtually indistinguishable from our own./+\ “You could almost draw a line through the hips—primitive above, modern below,” said Steve Churchill, a paleontologist from Duke University. “If you’d found the foot by itself, you’d think some Bushman had died.”/+\

“But then there was the head. Four partial skulls had been found—two were likely male, two female. In their general morphology they clearly looked advanced enough to be called Homo. But the braincases were tiny—a mere 560 cubic centimeters for the males and 465 for the females, far less than H. erectus’s average of 900 cubic centimeters, and well under half the size of our own. A large brain is the sine qua non of humanness, the hallmark of a species that has evolved to live by its wits. These were not human beings. These were pinheads, with some humanlike body parts.” /+\

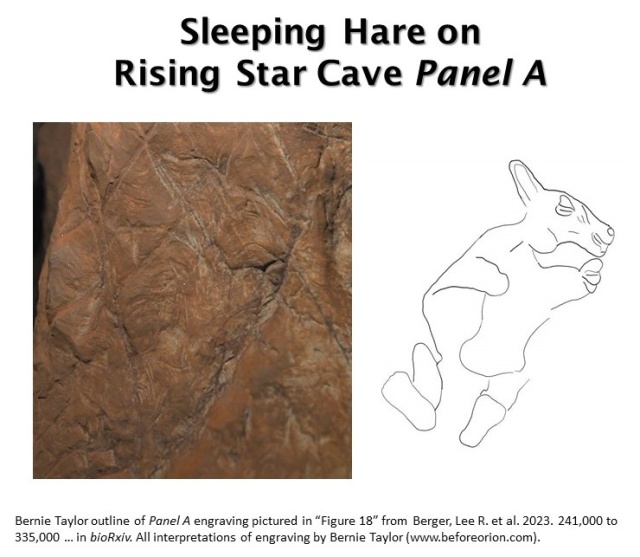

Discovering the Engravings in Rising Star Cave

Berger’s team discovered a number of engravings in Rising Star Cave in July 22. Alison George wrote in New Scientist: The team only discovered engravings when Berger entered them for the first time. He had to lose 25 kilograms of weight in order to squeeze through passages in the rock as narrow as 17.5 centimetres wide. “It was incredibly hard to get in, and I wasn’t sure I could get back out,” he says. To his amazement, Berger spotted some engravings on a natural pillar that forms the entrance to a passage connecting the Dinaledi chamber – where H. naledi fossils were first discovered – and the Hill antechamber, where other remains had been found. [Source: Alison George, New Scientist, June 5, 2023]

In three different areas of the walls, he saw geometric shapes, mainly composed of lines 5 to 15 centimetres long, deeply engraved into the dolomite stone. This is an incredibly hard rock, so the engravings would have taken considerable effort to make. Many of these lines intersect to form geometric patterns, such as squares, triangles, crosses and ladder shapes. “There was this moment of awe and surprise in seeing these highly recognisable symbols carved into the wall,” says Berger. “Seeing these symbols was entirely unexpected.”

We know that Neanderthals created similar symbols more than 64,000 years ago, as did modern humans in southern Africa from around 80,000 years ago. If the symbols in the Rising Star caves were indeed made by H. naledi, they could be far older. Berger argues that to go to the effort of engraving this incredibly hard rock “in what appear to be important positions within these extraordinarily remote places, the interpretation is that they must have some meaning”. Others are more cautious. “It is premature to conclude that symbolic markings were made by small-brained hominins, specifically H. naledi,” says Emma Pomeroy at the University of Cambridge. “While intriguing, exciting and suggestive, these findings require more evidence and analysis to support the substantial claims being made about them.”

No Homo Naledi DNA Yet

Despite the recovery of numerous Homo naledi fossils, recovering DNA from them has thus far been elusive.Jennifer Raff wrote in The Guardian: “On a bioarchaeological level (assuming we could get DNA from multiple individuals in the cave), we could ask whether H. naledi individuals buried in the cave were close relatives, and whether there was a relationship between burial location and genetic relatedness. The answers to these questions might give us some insights into the social structure of the species, whether the individuals buried within the cave constituted a single population close in time, or whether there is detectable genetic change over time in the individuals within the cave. We could also use the molecular clock to estimate the time of divergence of H. naledi to the other hominins. [Source: Jennifer Raff, The Guardian, May 23, 2017]

“Ancient DNA could answer a lot of questions regarding H. naledi’s ancestry and relationships, but unfortunately we’re not there yet. While the dates of these fossils fit comfortably within the range at which we can obtain ancient DNA (currently up to ~560–780,000 years ago), Berger et al. notes in their paper that “attempts to obtain aDNA from H. naledi remains have thus far proven unsuccessful.” One of the team members, Dr John Hawks, noted on twitter in a conversation with myself and others that three separate ancient DNA labs have actually made the attempt without any luck (ours at the University of Kansas wasn’t one of them, for the record), but that they will keep trying. |=|

“This is an important reminder of just how difficult and frustrating ancient DNA research can be, and if there’s anything I wish the interested public would know about it, it’s this: Behind the exciting news that comes out every month about this ancient genome or that lie scores of failed attempts, and the frustrated tears of many graduate students. |=|

“Ancient DNA preservation depends on many different variables, such as the temperature(s), UV radiation, and pH the remains have been subjected to, the type of bone, tooth, or tissue being sampled, and the amount of water, salinity, microbes, and oxygen present in the depositional context. This is why some very ancient bones will yield their genetic secrets, while ones just a few hundreds of years old won’t no matter how hard you try. Furthermore, morphological preservation of bone doesn’t always correspond with biomolecular preservation, and we can’t necessarily know in advance whether DNA will be present in a skeleton before we attempt to recover it. Thus ancient DNA researchers must always be mindful about addressing important questions, be responsible about sampling fossils, and not commit too many resources (particularly money and time) to samples which won’t work. Knowing when to stop working on a sample that won’t yield DNA is almost as important as determining which samples to attempt in the first place.

“Will we ever get a H. naledi genome? Based on the hints we’ve gotten so far, the odds don’t look great. Just as with H. floresiensis, the other small-brained hominin that persisted until quite recently (50,000 years ago), their position in our family tree looks to remain unclear for a while - a lesson to us about how much we still have to learn. But if I weren’t relentlessly optimistic, I wouldn’t have lasted long in the world of ancient DNA research. Perhaps it will just take a little more time and luck. We’ve certainly seen these two variables in abundance throughout the remarkable story of H. naledi’s discovery.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024