ANCIENT ROMAN ART

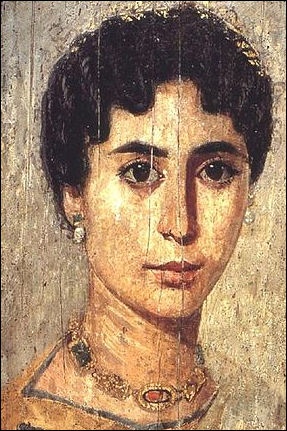

Roman-era Fayum mummy portrait from Egypt

Roman art tended to be realistic while Greek art was idealized. Roman artistic innovations included equestrian statues, naturalistic busts, and decorative wall paintings like those found in Pompeii. The Romans liked adorn their public and private buildings and spaces with art with color and texture. Perhaps their greatest contribution to art was their mosaics. The word style is derived from the word “stilus,” the Roman writing instrument.

A lot of Roman art was an imitation of Greek art, much of it poor imitations, and judging from the way the Romans wrote about Greek art and their own arts seems to show they realized this as well. Greek art and culture arrived in Rome indirectly through the Etruscans and more directly through Greek colonies in Italy and by Roman plundering of Greek cities and offers of good pay for Greek artists in Rome.

The historian William C. Morey wrote: “As the Romans were a practical people, their earliest art was shown in their buildings. While the Romans could never hope to acquire the pure aesthetic spirit of the Greeks, they were inspired with a passion for collecting Greek works of art, and for adorning their buildings with Greek ornaments. They imitated the Greek models and professed to admire the Greek taste; so that they came to be, in fact, the preservers of Greek art.” [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~]

The dismissal of the Roman artists as mere copyists of the Greeks may be unfair. Maybe it is true with sculpture but is not true with painting as frescoes of Pompeii and the mummy shroud paintings in Roman-era Egypt show. The Romans were the first to employ the science of perspective in their art, a three-dimensional quality most notably employed in shroud paintings from the A.D. first to third century in the Egyptian areas of Hawara and Fayum but also present in some works from Pompeii. By comparison, some of the images of Greek vase paintings look like idealized stick figures. Perspective was not rediscovered until the Renaissance in the 13th century Italy.

Categories with related articles in this website: Early Ancient Roman History (34 articles) factsanddetails.com; Later Ancient Roman History (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Life (39 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Art and Culture (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Government, Military, Infrastructure and Economics (42 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ;

“Outlines of Roman History” forumromanum.org; “The Private Life of the Romans” forumromanum.org|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu;

Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org

The Roman Empire in the 1st Century pbs.org/empires/romans;

The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ;

Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors roman-emperors.org;

British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;

Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art;

The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ;

Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu;

Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ;

History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame /web.archive.org ;

United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Etruscan Art

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Much of what we know about the Etruscans comes not from historical evidence, but from their art and the archaeological record. Many Etruscan sites, primarily cemeteries and sanctuaries, have been excavated, notably at Veii, Cerveteri, Tarquinia, Vulci, and Vetulonia. Numerous Etruscan tomb paintings portray in vivid color many different scenes of life, death, and myth. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

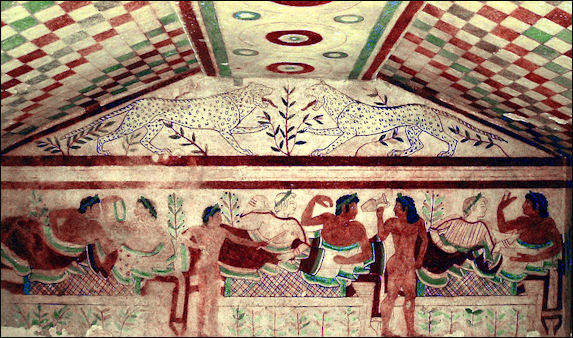

Etruscan painting

“From very early on, the Etruscans were in contact with the Greek colonies in southern Italy. Greek potters and their works influenced the development of Etruscan fine painted wares , and, consequently, new types of Etruscan pottery were created during the Orientalizing period (ca. 750–575 B.C.) and subsequent Archaic period (ca. 575–490 B.C.). The most successful of these pottery styles is known as Bucchero, characterized by its shiny black surface and preponderance of shapes that emulate metal prototypes. An Etruscan dedication at the Greek sanctuary of Delphi attests to the close interaction between the Greeks and the Etruscans in the Archaic period. The Etruscans particularly prized finely painted Greek vases, which they collected in great numbers. Likewise, their interest in Greek art and culture is manifest in works by Etruscan artists. However, the adaptation of Greek iconography to Etruscan art is complex and difficult to interpret. \^/

“Etruria, the region occupied by the Etruscans, was rich in metals, particularly copper and iron. The Etruscans were master bronze smiths who exported their finished products all over the Mediterranean. Finely worked bronzes, such as thrones and chariots decorated with exquisite hammered reliefs, cast statues and statuettes, as well as ornate vessels, mirrors, and stands, attest to the high quality achieved by Etruscan artists, particularly in the Archaic and Classical (ca. 490–300 B.C.) periods. Opulent jewelry of gold and semi-precious stones exemplifies eastern Greek and Levantine forms adapted to Etruscan taste. Extensive trade in the Mediterranean during this period supplied artists with exotic materials such as ivory, amber, ostrich eggs, and semi-precious stones, all of which fostered the development of Etruscan gem engraving and other arts. The Etruscans were also well known for their terracotta freestanding sculpture and architectural reliefs. Etruscan funerary works, particularly sarcophagi and cinerary urns , often carved in high relief, comprise an especially rich source of evidence for artistic achievement during the Late Classical and Hellenistic periods.

Examples of Etruscan Art

Etruscan art includes monumental tombs, tomb paintings, painted vases, urns with reliefs, bronze mirrors, gold and silver jewelry and alabaster, terra cotta and limestone figurines.The Etruscans produced great tomb art, bronzes and terra-cotta sculptures. The Etruscan Museum of Tarquinia has many fine pieces including a room full of magnificent sarcophagi topped by reclining figures and sometimes etched with puzzling epigraphs that scholars have had difficulty deciphering. There are also funeral urns and vases. The most beautiful vase is an imported one from Greece that contains an image of a woman's head with a beguiling expression.. Most of the prize pieces are at the Villa Giulia in Rome.

The Etruscans also made intriguing, highly-stylized narrow bronze figures that were offered as votive offerings at temples; realistic, detailed equestrian statues; lovely and distinct “ bucchero” pottery, which were deliberately fired to look like metal.

There is evidence of monumental art, including bold reliefs and some of the earliest architectural terra cottas. The Etruscans built large acropolises and the largest buildings in Italy before the 6th century B.C. The only impressive monument left is the fortified city gate of Porta Augusta in Perugia from the second century B.C. Porta Augusta is also important in that it is one of the oldest places in Italy with an arch.

The Etruscans were among the leading importers of Greek vases. Some of the most beautiful Greek vases found by archaeologists have been unearthed at Etruscan sites.

Etruscan Ivy wreath

National Etruscan Museum at Villa Giulia (Villa Borghese) in Rome is probably the finest Etruscan museum in the world. Among the treasures are a painted ostrich egg, imported from Africa but believed to have been painted in Etruria; a beautiful sarcophagus of married couple, which shows the husband gently caressing his wife on her arm and shoulder; a statue of a satyr with a taller woman doing a dance that bears an uncanny resemblance to the 1970s’s dance, the bump; pair of wooden sandals imprinted with the owners toeprints; and a burial urn shaped like a thatched hut. Among the gold items are a necklace with two pendants of chubby woman's face and a third implanted with an onyx that looks like a human eyeball; and a broach decorated with a werewolf-like hoofed satyr with a is granulated background, an effect that jewelers today can't duplicate. The most important pieces are three gold tablets; two of which are inscribed in Etruscan and the third in Phoenician, the language of Carthage. The Etruscan language still hasn't been completely deciphered.

Archeological Museum in Florence has one of the best Etruscan collections outside of Rome's Villa Giulia. It contains Roman Etruscan pieces once housed in the Uffizi. One particularly amazing bronze statue shows a charging lion with a goat coming out of its back that in turn is being grabbed by the lion's tail which is a serpent. Also check out delightful Etruscan bronze of a boy's head and youth with the bare-breasted Demon of Death. The Egyptian

Etruscan Tomb Art

Tomb paintings include images of funeral ceremonies, athletic competitions, bloody duels, grand banquets, warriors and horsemen, demons and mythical creatures, and journeys to the next world. There are images of bearded snakes, dolphins, flocks of birds, musicians, wild dancers and jugglers. The vibrant colors were created with an array of pigments, some of them quite rare and expensive: white from calcite, red from hematite, black from charcoal, yellow from goethite, and blue from a mixture if silica, lime, copper and a special alkali imported from Egypt.

Few of the tombs with wall paintings are open to the public. Once a sealed tomb has been opened the paintings decays rapidly in the humidity. One tomb called the Tomb of the Leopards has beautiful wall paintings that depict nude wrestlers, men playing musical and a banqueting couple looking upon an egg, a symbol of immortality.

The Etruscan Museum in the Vatican contains one of the world's best collections of Etruscan art. The most outstanding pieces, which were found in Etruscan tombs in Tuscany and Lazio, include gold and silver jewelry, dice that looks just like modern dice, chariots, vase paintings, and small sarcophagi that held the cremated remains of wealthy Etruscans. Among the highlights are lovely Etruscan painting and a bronze statue of boy from the Etruscan site of Tarquina.

Etruscan Tarquinia Tomb of the Leopards

Arts Under Augustus and Trajan

Augustus (reigned 27 B.C.–14 A.D.) promoted learning and patronized the arts. Virgil, Horace, Livy and Ovid wrote during the “Augustan Age," Augustus also established what has been described as the first paleontology museum on Capri. It contained the bones of extinct creatures. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the reign of Augustus, Rome was transformed into a truly imperial city. By the first century B.C., Rome was already the largest, richest, and most powerful city in the Mediterranean world. During the reign of Augustus, however, it was transformed into a truly imperial city. Writers were encouraged to compose works that proclaimed its imperial destiny: the Histories of Livy, no less than the Aeneid of Virgil, were intended to demonstrate that the gods had ordained Rome "mistress of the world." A social and cultural program enlisting literature and the other arts revived time-honored values and customs, and promoted allegiance to Augustus and his family. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

The emperor was recognized as chief state priest, and many statues depicted him in the act of prayer or sacrifice. Sculpted monuments, such as the Ara Pacis Augustae built between 14 and 9 B.C., testify to the high artistic achievements of imperial sculptors under Augustus and a keen awareness of the potency of political symbolism. Religious cults were revived, temples rebuilt, and a number of public ceremonies and customs reinstated. Craftsmen from all around the Mediterranean established workshops that were soon producing a range of objects—silverware, gems, glass—of the highest quality and originality. Great advances were made in architecture and civil engineering through the innovative use of space and materials. By 1 A.D., Rome was transformed from a city of modest brick and local stone into a metropolis of marble with an improved water and food supply system, more public amenities such as baths, and other public buildings and monuments worthy of an imperial capital.” \^/

During Trajan’s reign (98–117 A.D.) period Roman art reached its highest development. The art of the Romans, as we have before noticed, was modeled in great part after that of the Greeks. While lacking the fine sense of beauty which the Greeks possessed, the Romans yet expressed in a remarkable degree the ideas of massive strength and of imposing dignity. In their sculpture and painting they were least original, reproducing the figures of Greek deities, like those of Venus and Apollo, and Greek mythological scenes, as shown in the wall paintings at Pompeii. Roman sculpture is seen to good advantage in the statues and busts of the emperors, and in such reliefs as those on the arch of Titus and the column of Trajan. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~]

Luxury Arts of Rome

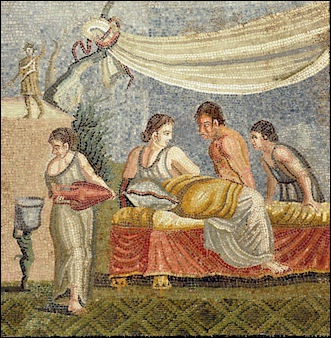

mosaic from a villa

Christopher Lightfoot of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “During the late Republic, wealth poured into Rome on an unprecedented scale in the form of tribute, taxes, and profits from commerce and banking. Not all of the riches were honestly or legitimately acquired, for some came in the form of booty and spoils, including defeated enemies of Rome that were enslaved. It did mean, however, that a few leading men, such the general and politician Marcus Licinius Crassus (ca. 115–53 B.C.), became enormously rich. Such wealth was used principally to secure success in the intense political rivalry that afflicted Rome at that time, but it also stimulated patronage of the arts, the formation of libraries and art collections, and the construction of palaces and gardens. [Source: Christopher Lightfoot, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Although Rome's first emperor, Augustus, attempted to curb these extravagances and excessive displays of personal wealth, well-to-do Romans increasingly indulged their taste for luxury during the Julio-Claudian period (27 B.C.–68 A.D.). In addition to spending fortunes on sumptuous villas, lavish entertainment, fashionable clothes, and entourages of slaves and hangers-on, men and women in high Roman society furnished themselves with a range of expensive personal items. Alon with gold jewelry such as earrings, necklaces, and finger rings, the Romans loved expensive silver mirrors, ivory combs and hairpins, and an assortment of boxes and containers for perfumes and cosmetics. These precious items give an indication of the variety and quality of the craftsmanship that was required to provide for the needs of wealthy Roman clients. Other accessories, known only from literary sources, were in more perishable materials, such as costly silks imported from China or flamboyant wigs made from the hair of German or British slaves. Ivory was also imported to Rome mainly from Africa via the Nile. \^/

“Roman ladies also developed a taste for elaborate jewelry decorated with colorful, exotic stones. Amber and pearl were two of the most popular and sought after materials; the former was brought from the Baltic Sea, and the finest pearls were imported from the Persian Gulf, although one reason given to justify the conquest of Britain during the reign of emperor Claudius (41–54 A.D.) was that it was a rich source of pearls. Other rare and expensive gems included amethysts, sapphires, and uncut diamonds, all from various parts of southern Asia. These were prized for their brilliancy and transparency. Emeralds from the eastern desert of Upper Egypt were also very popular; they were usually left in their natural form as prisms, which were drilled and strung on gold necklaces, bracelets, and earrings. Many funerary portraits of women—particularly the painted mummy portraits from Roman Egypt (examples of which are on display in the Egyptian galleries) and the sculpted stone portraits from the caravan city of Palmyra in Syria (examples are exhibited in the Ancient Near East galleries)—show the deceased wearing such jewelry as a lasting indication of their social status and personal wealth. \^/

“Some luxury materials were so rare or costly that they gave rise to cheaper, manmade imitations in both pottery and glass, but even in these we can recognize a technical and artistic skill of the highest caliber. Such is the case with mosaic glass and marbled ceramic tablewares, made to reproduce the striking patterns of banded agate. Cameo glass, the most difficult and costly of all Roman glass, was also inspired by layered semiprecious stones. There are, for example, many Roman gems in cameo glass that were made as less expensive alternatives to real cameos in banded agate or sardonyx. In addition, it must be remembered that much has been irretrievably lost, especially objects in gold and silver, which could easily be melted down and reused. Others became heirlooms and relics that were later incorporated into medieval and Renaissance works, such as some of the semiprecious stone vessels in the Treasury of San Marco in Venice. \^/

“In the third century A.D., the Roman empire was beset by barbarian invasions in Europe, a renascent Sasanian Persian empire in the East, internal disorder, and rampant inflation. Nevertheless, the empire's accumulated resources meant that the privileged elite in Roman society continued to enjoy a life of untold wealth and luxury. One result of the increased dangers was that people buried their precious possessions and failed more often to return to collect them. Hoards of silver and jewelry have consequently been found in considerable numbers throughout the Roman world. There was certainly no diminution of skill and inventiveness of the craftsmen who produced these luxuries, but new styles in design and fashion developed. In particular, jewelry and ornaments became more colorful and garish, and they included the use of gold coins (an attractive but practical way to beat inflation). Such tastes led ultimately to the adoption by the emperors of ceremonial silk robes and regal-looking gold crowns, decorated with pearls and precious stones. It was to be a fashion that greatly influenced later Byzantine art, and even in the West the rulers of the successor kingdoms never completely forgot the wealth and splendor of ancient Rome.

Art of the Roman Provinces

Dying Gaul

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “At its greatest extent, the empire ruled by Rome reached around the Mediterranean Sea and stretched from northern England to Nubia, from the Atlantic to Mesopotamia. Roman rule united this vast and varied territory, and Roman administration integrated it economically and socially. A traveler making a tour of the several provinces around 212 A.D. (when citizenship was extended to all free-born males) would have found many similarities among the places that he or she visited: Roman coins circulated everywhere, and in every province there were cities adorned with statues of the emperor and buildings such as baths, basilicas, and amphitheaters that embodied Roman cultural and architectural norms. Each region nevertheless had its own history, its own local culture, and its own relationship with Rome. Art demonstrates both the scope and the limits of Roman influence, for the circulation of materials, methods, objects, and art forms created a certain cultural unity, and yet in each place, the persistence of local customs ensured the survival of cultural diversity. [Source: Jean Sorabella, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Gaul, a large region that roughly corresponds to modern France, provides a representative picture of the interaction between Roman and non-Roman traditions in the visual arts. Before the arrival of the Romans, metalwork was a highly developed craft among the Celts, whose artisans excelled in enriching metal objects with brightly colored abstract ornament; they seldom represented the human form, but when they did, they produced highly stylized figures quite alien to classical ideals. After the Romans arrived, Gallic craftsmen continued to work metal in sophisticated ways, but their output changed to serve the needs of society as it adopted Roman manners. Workshops in Gaul turned to produce vessels and tableware suited to a Romanized style of dining; they also applied techniques that the Romans admired, such as champlevé enamel, to ornaments designed for Roman buyers. Some objects made in Gaul were meant for local use, like statuettes of native divinities with distinctly un-Roman traits; other types of work were widely exported, such as six-sided boxes decorated with millefiore enamel and fine relief pottery known as terra sigillata. In addition to producing works of art, the people of Gaul also imported objects, expertise, and stylistic preferences from the capital: the cities of the province were thus outfitted with monumental statuary and buildings of Roman types, and the environs of these cities were served by roads and aqueducts. \^/

“The provinces of northern Africa also saw urban development in the Roman mold. The city of Timgad (modern-day Algeria), established by Trajan in 100 A.D., made use of a rigidly ordered grid plan, common to colonial settlements all over the empire, and some of the best preserved examples of Roman public buildings, including a theater, ampitheater, temple, and marketplace, are still to be found in Leptis Magna (in modern-day Libya), the birthplace of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211). Romanization went hand in hand with economic prosperity, as the city of Rome looked to North Africa to supply its wheat, oil, and wine, and agricultural productivity no doubt contributed to the distribution around the Mediterranean of distinctive red slip pottery vessels produced in Tunisian workshops. In many respects, the North African provinces became as Roman as any on the Italian peninsula, spawning intellectual figures steeped in Roman learning, such as the novelist Apuleius of Madaurus (ca. 125–ca. 180 A.D.) and the Christian writers Tertullian (ca. 160–ca. 220 A.D.) and Saint Augustine of Hippo (354–430 A.D.). Their public and private spaces were adorned with the markers of Roman prosperity: courtyards and gardens, conspicious displays of freestanding sculpture, and, most especially, elegant and original mosaics, an art form for which North African artists showed particular talent. \^/

“The artistic output of each of the Roman provinces represents a mix of local and imperial traditions. Subject people continued to use their native languages, although official business was conducted in Latin or Greek; indigenous religions persisted, although sacrifices were everywhere offered for the emperor and the gods of the Roman pantheon. Visual culture too reflected the hybrid character of provincial civilization. Images of Roman style and message circulated widely, and yet craftsmen and consumers in the provinces maintained their own traditions, adopting Roman techniques and tastes as it suited them. \^/

“The funerary arts of the provinces demonstrate the variety and freedom of artistic expression in the several regions of the Roman empire. Since portraits and grave goods figure in many of the customs used to commemorate the dead, they also reflect the different styles of dress and approaches to representation preferred in various places. In Noricum and Pannonia in the Danubian basin, for instance, it was common to mark burials with busts of the deceased carved in relief, often in a naturalistic style like that used in Roman portraits and sometimes framed with moldings of classical design. The men depicted usually wear the toga, the proud costume of the Roman citizen, but the women sport instead a distinctive native fashion, with collars of heavy jewelry, prominent brooches at the shoulders, and cylindrical hats adorned with veils. The funerary portraiture of the Fayum oasis in Egypt displays a different mix of cultural preferences. The people here perpetuated the ancient custom of mummification, replacing the sculpted mask of earlier practice with a painted portrait. The context of these pictures is decidedly Egyptian, but the style of representation reflects the Greek tradition: the most refined examples demonstrate a remarkable degree of naturalism, and the costumes and hairstyles worn by both men and women adhere closely to Roman imperial fashions. The people of Palmyra in present-day Syria buried their dead in compartments cut into the walls of extensive cemetery complexes and closed each tomb with a limestone relief bearing a likeness of the dead. Some of the figures represented assume Roman garb and manners, but many more appear in oriental dress, with jewelry of local design; nearly all depict their subjects frontally, with disproportionately large eyes and boldly schematized features that display an approach to portraiture quite independent of Roman tendencies. \^/

Roman glassware, including a baby bottle from Apulum

“The diversity of customs followed in the disparate regions naturally resulted in artistic variety, but practices imposed by the Romans and observed throughout the empire also produced a lively range of responses. For example, the organization of urban society in the provinces granted high position to local elites, and members of this class often furnished their cities with buildings, monuments, and entertainments intended to display adherence to Roman ideals as well as the donor's largesse. For example, a local landholder who had been high priest in the cult of the Roman emperor erected an arch of recognizably Roman design at Saintes in southern France in 19 A.D., and in Barcelona in the early second century A.D., a father and son who both had attained senatorial rank and held consular office constructed a public bath on their own land. Sometimes the population of a whole town obtained imperial permission to set up a statue of the emperor or to build a temple in his honor. For the most part, such monuments took conventional forms: the emperor's portrait usually conformed to an official type probably devised in Rome itself. Some honorific images, however, reflected local traditions as well as or instead of the Roman standard. In the Greek-speaking lands of the eastern Mediterranean, for instance, the emperor's likeness was often mounted on an ideal nude body, as was common in the Hellenistic royal statues familiar there, and along the Nile, at Dendur, local people built a small temple on Egyptian architectural principles and decorated it with reliefs depicting the emperor Augustus in the guise of a pharaoh bringing offerings to Egyptian deities. \^/

“Finally, Roman rule facilitated trade among disparate regions, and this had a profound impact on art in the provinces. The circulation of marble and minerals suited to making pigments bound disparate regions to the capital and made possible the many-colored richness of much Roman architecture; the different types of stone used in the Pantheon, for instance, include yellow marble (giallo antico) from Tunisia, dramatically veined marble (pavonazzetto) from Asia Minor, green marbles from parts of Greece, flecked granites and deep red porpyhry from Egypt. The Romans also recognized and encouraged local industries in ways that ensured a wide range to some provincial products; iron works in Gaul and the Danubian basin, for example, operated as imperial manufactories producing weapons for Roman soldiers, and the Roman taste for glass ensured support first for the flourishing glassworks of Palestine and then for the proliferation of glass vessels and glass-making techniques throughout the empire. The army brought many Roman customs and products to distant locales, for recruits were often steeped in Roman culture even if they hailed from the provinces; excavations of military installations throughout the provinces have yielded glassware and small-scale statuary of standard Roman style. Philostratus, a Greek writer living in Rome in the third century A.D., marveled at the accomplished champlevé enamel of "barbarian" artists living in Gaul and Britain. Colorful enamel objects, from brooches to vessels to horse trappings, survive from sites throughout the empire and attest to the widespread appreciation for the distinctive achievements of artists working in its outer territories.

Secret Cabinet and the National Archaeological Museum in Naples

The National Archaeological Museum in Naples is one of the largest and best archeological museums in the world. Located with a 16th century palazzo, it houses a wonderful collection of statues, wall paintings, mosaics and everyday utensils, many of them unearthed in Pompeii and Herculaneum. In fact, most of the outstanding and well-preserved pieces from Pompeii and Herculaneum are in the archeological museum.

Among the treasures are majestic equestrian statues of proconsul Marcus Nonius Balbus, who helped restore Pompeii after the A.D. 62 earthquake; the Farnese Bull, the largest known ancient sculpture; the statue of Doryphorus, the spear bearer, a Roman copy of one of classical Greece's most famous statues; and huge voluptuous statues of Venus, Apollo and Hercules that bear witness to Greco-Roman idealizations of strength, pleasure, beauty and hormones.

The most famous work in the museum is the spectacular and colorful mosaic known both as “the Battle of Issus “ and “Alexander and the Persians” . Showing Alexander the Great battling King Darius and the Persians,, the mosaic was made from 1.5 million different pieces, almost all of them cut individually for a specific place on the picture. Other Roman mosaics range from simple geometric designs to breathtaking complex pictures.

Also worth look are the most outstanding artifacts found at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum are located here. The most unusual of these are the dark bronze statues of water carriers with spooky white eyes made of glass paste. A wall painting of peaches and a glass jar from Herculaneum could easily be mistaken for a Cezanne painting. In another colorful wall painting from Herculaneum a dour Telephus is being seduced by a naked Hercules while a lion, a cupid, a vulture and an angel look on.

Other treasures include the statue of an obscene male fertility god eying a bathing maiden four times his size; a beautiful portrait of a couple holding a papyrus scroll and a waxed tablet to show their importance; and wall paintings of Greek myths and theater scenes with comic and tragic masked actors. Make sure to check out the Farnese Cup in the Jewels collection. The Egyptian collection is often closed.

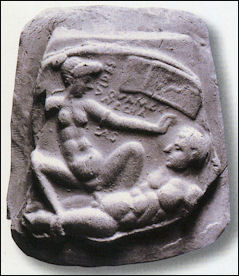

The Secret Cabinet (in National Archaeological Museum) is a couple of rooms with erotic sculptures, artifacts and frescoes from ancient Rome and Etruria that were locked away for 200 years. Unveiled in the year 2000, the two rooms contain 250 frescoes, amulets, mosaics, statues, oil laps,, votive offerings, fertility symbols and talismans. The objects include a second-century marble statute of the mythological figure Pan copulating with a goat found at the Valli die Papyri un 1752. Many of the objects were found in bordellos in Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The collection began with as a royal museum for obscene antiques started by the Bourbon King Ferdinand in 1785. In 1819, the objects were moved to a new museum where they were displayed until 1827, when it was closed after complaints by a priest that descried the room as hell and a "corrupter of the morals or modest youth." The room was opened briefly after Garibaldi set up a dictatorship in southern Italy in 1860.

Porphyry: On Images

fresco from Pompeii

Porphyry (A.D. c. 234 – c. 305) was a leading "Neoplatonist", who sought to defend "reason". As Christianity spread, there was a strong, negative intellectual reaction to it among the classically oriented intellectuals. In some of his works he attacks Christian unreason. In others he defends traditional Roman (Pagan) religion. The following fragments, passed on to use by Eusebius (c. A.D. 260-340), are related to cult images and images of Roman-era gods.

Porphyry wrote: Fragment 1: “I speak to those who lawfully may hear: Depart all ye profane, and close the doors. The thoughts of a wise theology, wherein men indicated God and God's powers by images akin to sense, and sketched invisible things in visible forms, I will show to those who have learned to read from the statues as from books the things there written concerning the gods. Nor is it any wonder that the utterly unlearned regard the statues as wood and stone, just as also those who do not understand the written letters look upon the monuments as mere stones, and on the tablets as bits of wood, and on books as woven papyrus.” [Source: “On Images” Porphyry (A.D. 232/3-c.305), drawn from fragments in Eusebius (c. A.D. 260-340), translated by Edwin Hamilton Gifford, MIT]

Fragment 2: “As the deity is of the nature of light, and dwells in an atmosphere of ethereal fire, and is invisible to sense that is busy about mortal life, He through translucent matter, as crystal or Parian marble or even ivory, led men on to the conception of his light, and through material gold to the discernment of the fire, and to his undefiled purity, because gold cannot be defiled. On the other hand, black marble was used by many to show his invisibility; and they moulded their gods in human form because the deity is rational, and made these beautiful, because in those is pure and perfect beauty; and in varieties of shape and age, of sitting and standing, and drapery; and some of them male, and some female, virgins, and youths, or married, to represent their diversity. Hence they assigned everything white to the gods of heaven, and the sphere and all things spherical to the cosmos and to the sun and moon in particular, but sometimes also to fortune and to hope: and the circle and things circular to eternity, and to the motion of the heaven, and to the zones and cycles therein; and the segments of circles to the phases of the moon; pyramids and obelisks to the element of fire, and therefore to the gods of Olympus; so again the cone to the sun, and cylinder to the earth, and figures representing parts of the human body to sowing and generation.”

Fragment 4: “They have made Hera the wife of Zeus, because they called the ethereal and aerial power Hera. For the ether is a very subtle air.”

Fragment 5: “And the power of the whole air is Hera, called by a name derived from the air: but the symbol of the sublunar air which is affected by light and darkness is Leto; for she is oblivion caused by the insensibility in sleep, and because souls begotten below the moon are accompanied by forgetfulness of the Divine; and on this account she is also the mother of Apollo and Artemis, who are the sources of light for the night.”

Fragment 6: “The ruling principle of the power of earth is called Hestia, of whom a statue representing her as a virgin is usually set up on the hearth; but inasmuch as the power is productive, they symbolize her by the form of a woman with prominent breasts. The name Rhea they gave to the power of rocky and mountainous land, and Demeter to that of level and productive land. Demeter in other respects is the same as Rhea, but differs in the fact that she gives birth to Kore by Zeus, that is, she produces the shoot from the seeds of plants. And on this account her statue is crowned with ears of corn, and poppies are set round her as a symbol of productiveness.”

Porphyry: On Images: Fragment 3

Porphyry (A.D. c. 234 – c. 305) wrote in Fragment 3: 'Now look at the wisdom of the Greeks, and examine it as follows. The authors of the Orphic hymns supposed Zeus to be the mind of the world, and that he created all things therein,containing the world in himself. Therefore in their theological systems they have handed down their opinions concerning him thus:'

Emperor Claudius striking a Zeus pose

“Zeus was the first, Zeus last, the lightning's lord,

Zeus head, Zeus centre, all things are from Zeus.

Zeus born a male, Zeus virgin undefiled;

Zeus the firm base of earth and starry heaven;

Zeus sovereign, Zeus alone first cause of all:

One power divine, great ruler of the world,

One kingly form, encircling all things here,

Fire, water, earth, and ether, night and day;

Wisdom, first parent, and delightful Love:

For in Zeus' mighty body these all lie.

His head and beauteous face the radiant heaven

Reveals and round him float in shining waves

The golden tresses of the twinkling stars.

On either side bulls' horns of gold are seen,

Sunrise and sunset, footpaths of the gods.

His eyes the Sun, the Moon's responsive light;

His mind immortal ether, sovereign truth,

Hears and considers all; nor any speech,

Nor cry, nor noise, nor ominous voice escapes

The ear of Zeus, great Kronos' mightier son:

Such his immortal head, and such his thought.

His radiant body, boundless, undisturbed

In strength of mighty limbs was formed thus:

The god's broad-spreading shoulders, breast and back

Air's wide expanse displays; on either side

Grow wings, wherewith throughout all space he flies.

Earth the all-mother, with her lofty hills,

His sacred belly forms; the swelling flood

Of hoarse resounding Ocean girds his waist.

His feet the deeply rooted ground upholds,

And dismal Tartarus, and earth's utmost bounds.

All things he hides, then from his heart again

In godlike action brings to gladsome light.

[Source: “On Images” Porphyry (A.D. 232/3-c.305), drawn from fragments in Eusebius (c. A.D. 260-340), translated by Edwin Hamilton Gifford, MIT]

“Zeus, therefore, is the whole world, animal of animals, and god of gods; but Zeus, that is, inasmuch as he is the mind from which he brings forth all things, and by his thoughts creates them. When the theologians had explained the nature of god in this manner, to make an image such as their description indicated was neither possible, nor, if any one thought of it, could he show the look of life, and intelligence, and forethought by the figure of a sphere.

“But they have made the representation of Zeus in human form, because mind was that according to which he wrought, and by generative laws brought all things to completion; and he is seated, as indicating the steadfastness of his power: and his upper parts are bare, because he is manifested in the intellectual and the heavenly parts of the world; but his feet are clothed, because he is invisible in the things that lie hidden below. And he holds his sceptre in his left hand, because most close to that side of the body dwells the heart, the most commanding and intelligent organ: for the creative mind is the sovereign of the world. And in his right hand he holds forth either an eagle, because he is master of the gods who traverse the air, as the eagle is master of the birds that fly aloft - or a victory, because he is himself victorious over all things.”

Porphyry: On Images: Fragment 7

Porphyry (A.D. c. 234 – c. 305) wrote in Fragment 7: “But since there was in the seeds cast into the earth a certain power, which the sun in passing round to the lower hemisphere drags down at the time of the winter solstice, Kore is the seminal power, and Pluto the sun passing under the earth, and traversing the unseen world at the time of the winter solstice; and he is said to carry off Kore, who, while hidden beneath the earth, is lamented by her mother Demeter. [Source: “On Images” Porphyry (A.D. 232/3-c.305), drawn from fragments in Eusebius (c. A.D. 260-340), translated by Edwin Hamilton Gifford, MIT]

“The power which produces hard-shelled fruits, and the fruits of plants in general, is named Dionysus. But observe the images of these also. For Kore bears symbols of the production of the plants which grow above the earth in the crops: and Dionysus has horns in common with Kore, and is of female form, indicating the union of male and female forces in the generation of the hard shelled fruits.

sarcophagus with Bacchnal scenes

“But Pluto, the ravisher of Kore, has a helmet as a symbol of the unseen pole, and his shortened sceptre as an emblem of his kingdom of the nether world; and his dog indicates the generation of the fruits in its threefold division - the sowing of the seed, its reception by the earth, its growing up. For he is called a dog, not because souls are his food, but because of the earth's fertility, for which Pluto provides when he carries off Kore.

“Attis, too, and Adonis are related to the analogy of fruits. Attis is the symbol of the blossoms which appear early in the spring, and fall off before the complete fertilization; whence they further attributed castration to him, from the fruits not having attained to seminal perfection: but Adonis was the symbol of the cutting of the perfect fruits.

“Silenus was the symbol of the wind's motion, which contributes no few benefits to the world. And the flowery and brilliant wreath upon his head is symbolic of the revolution of the heaven, and the hair with which his lower limbs are surrounded is an indication of the density of the air near the earth.

“Since there was also a power partaking of the prophetic faculty, the power is called Themis, because of its telling what is appointed and fixed for each person.

“In all these ways, then, the power of the earth finds an interpretation and is worshipped: as a virgin and Hestia, she holds the centre; as a mother she nourishes; as Rhea she makes rocks and dwells on mountains; as Demeter, she produces herbage; and as Themis, she utters oracles: while the seminal law which descends into her bosom is figured as Priapus, the influence of which on dry crops is called Kore, and on soft fruits and shellfruits is called Dionysus. For Kore was carried off by Pluto, that is, the sun going; down beneath the earth at seed-time; but Dionysus begins to sprout according to the conditions of the power which, while young, is hidden beneath the earth, yet produces fine fruits, and is an ally of the power in the blossom symbolized by Attis, and of the cutting of the ripened corn symbolized by Adonis.

“Also the power of the wind which pervades all things is formed into a figure of Silenus, and the perversion to frenzy into a figure of a Bacchante, as also the impulse which excites to lust is represented by the Satyrs. These, then, are the symbols by which the power of the earth is revealed.”

Porphyry: On Images: Fragment 8

Porphyry (A.D. c. 234 – c. 305) wrote in Fragment 8: “The whole power productive of water they called Oceanus, and named its symbolic figure Tethys. But of the whole, the drinking-water produced is called Achelous; and the sea-water Poseidon; while again that which makes the sea, inasmuch as it is productive, is Amphitrite. Of the sweet waters the particular powers are called Nymphs, and those of the sea-waters Nereids. [Source: “On Images” Porphyry (A.D. 232/3-c.305), drawn from fragments in Eusebius (c. A.D. 260-340), translated by Edwin Hamilton Gifford, MIT]

“Again, the power of fire they called Hephaestus, and have made his image in the form of a man, but put on it a blue cap as a symbol of the revolution of the heavens, because the archetypal and purest form of fire is there. But the fire brought down from heaven to earth is less intense, and wants the strengthening and support which is found in matter: wherefore he is lame, as needing matter to support him.

“Also they supposed a power of this kind to belong to the sun and called it Apollo, from the pulsation of his beams. There are also nine Muses singing to his lyre, which are the sublunar sphere, and seven spheres of the planets, and one of the fixed stars. And they crowned him with laurel, partly because the plant is full of fire, and therefore hated by daemons; and partly because it crackles in burning, to represent the god's prophetic art.

cubiculum in a villa at Boscoreale near Pompeii

“But inasmuch as the sun wards off the evils of the earth, they called him Heracles (from his clashing against the air) in passing from east to west. And they invented fables of his performing twelve labours, as the symbol of the division of the signs of the zodiac in heaven; and they arrayed him with a club and a lion's skin, the one as an indication of his uneven motion, and the other representative of his strength in "Leo" the sign of the zodiac.

“Of the sun's healing power Asclepius is the symbol, and to him they have given the staff as a sign of the support and rest of the sick, and the serpent is wound round it, as significant of his preservation of body and soul: for the animal is most full of spirit, and shuffles off the weakness of the body. It seems also to have a great faculty for healing: for it found the remedy for giving clear sight, and is said in a legend to know a certain plant which restores life.

“But the fiery power of his revolving and circling motion, whereby he ripens the crops, is called Dionysus, not in the same sense as the power which produces the juicy fruits, but either from the sun's rotation, or from his completing his orbit in the heaven. And whereas he revolves round the cosmical seasons and is the maker of "times and tides," the sun is on this account called Horus.

“Of his power over agriculture, whereon depend the gifts of wealth, the symbol is Pluto. He has, however, equally the power of destroying, on which account they make Sarapis share the temple of Pluto: and the purple tunic they make the symbol of the light that has sunk beneath the earth, and the sceptre broken at the top that of his power below, and the posture of the hand the symbol of his departure into the unseen world.

“Cerberus is represented with three heads, because the positions of the sun above the earth are three-rising, midday, and setting.

“The moon, conceived according to her brightness, they called Artemis, as it were, "cutting the air." And Artemis, though herself a virgin, presides over childbirth, because the power of the new moon is helpful to parturition.

“What Apollo is to the sun, that Athena is to the moon: for the moon is a symbol of wisdom, and so a kind of Athena.

“But, again, the moon is Hecate, the symbol of her varying phases and of her power dependent on the phases. Wherefore her power appears in three forms, having as symbol of the new moon the figure in the white robe and golden sandals, and torches lighted: the basket, which she bears when she has mounted high, is the symbol of the cultivation of the crops, which she makes to grow up according to the increase of her light: and again the symbol of the full moon is the goddess of the brazen sandals.

“Or even from the branch of olive one might infer her fiery nature, and from the poppy her productiveness, and the multitude of the souls who find an abode in her as in a city, for the poppy is an emblem of a city. She bears a bow, like Artemis, because of the sharpness of the pangs of labour.

“And, again, the Fates are referred to her powers, Clotho to the generative, and Lachesis to the nutritive, and Atropos to the inexorable will of the deity.

“Also, the power productive of corn-crops, which is Demeter, they associate with her, as producing power in her. The moon is also a supporter of Kore. They set Dionysus also beside her, both on account of their growth of horns, and because of the region of clouds lying beneath the lower world.

“The power of Kronos they perceived to be sluggish and slow and cold, and therefore attributed to him the power of time: and they figure him standing, and grey-headed, to indicate that time is growing old.

“The Curetes, attending on Chronos, are symbols of the seasons, because time journeys on through seasons.

“Of the Hours, some are the Olympian, belonging to the sun, which also open the gates in the air: and others are earthly, belonging to Demeter, and hold a basket, one symbolic of the flowers of spring, and the other of the wheat-ears of summer.

“The power of Ares they perceived to be fiery, and represented it as causing war and bloodshed, and capable both of harm and benefit.

Pompeii fresco

“The star of Aphrodite they observed as tending to fecundity, being the cause of desire and offspring, and represented it as a woman because of generation, and as beautiful, because it is also the evening star -

“"Hesper, the fairest star that shines in heaven." [Homer, Iliad 22:318]

“And Eros they set by her because of desire. She veils her breasts and other parts, because their power is the source of generation and nourishment. She comes from the sea, a watery element, and warm, and in constant movement, and foaming because of its commotion, whereby they intimate the seminal power.

“Hermes is the representative of reason and speech, which both accomplish and interpret all things. The phallic Hermes represents vigour, but also indicates the generative law that pervades all things.

“Further, reason is composite: in the sun it is called Hermes; in the moon Hecate; and that which is in the All Hermopan, for the generative and creative reason extends over all things. Hermanubis also is composite, and as it were half Greek, being found among the Egyptians also. Since speech is also connected with the power of love, Eros represents this power: wherefore Eros is represented as the son of Hermes, but as an infant, because of his sudden impulses of desire.

“They made Pan the symbol of the universe, and gave him his horns as symbols of sun and moon, and the fawn skin as emblem of the stars in heaven, or of the variety of the universe.

Porphyry: On Images: Fragment 10

Porphyry (A.D. c. 234 – c. 305) wrote in Fragment 10: “The Demiurge, whom the Egyptians call Cneph, is of human form, but with a skin of dark blue, holding a girdle and a sceptre, and crowned with a royal wing on his head, because reason is hard to discover, and wrapt up in secret, and not conspicuous, and because it is life-giving, and because it is a king, and because it has an intelligent motion: wherefore the characteristic wing is put upon his head. [Source: “On Images” Porphyry (A.D. 232/3-c.305), drawn from fragments in Eusebius (c. A.D. 260-340), translated by Edwin Hamilton Gifford, MIT]

“This god, they say, puts forth from his mouth an egg, from which is born a god who is called by themselves Phtha, but by the Greeks Hephaestus; and the egg they interpret as the world. To this god the sheep is consecrated, because the ancients used to drink milk.

“The representation of the world itself they figured thus: the statue is like a man having feet joined together, and clothed from head to foot with a robe of many colours, and has on the head a golden sphere, the first to represent its immobility, the second the many-coloured nature of the stars, and the third because the world is spherical.

“The sun they indicate sometimes by a man embarked on a ship, the ship set on a crocodile. And the ship indicates the sun's motion in a liquid element: the crocodile potable water in which the sun travels. The figure of the sun thus signified that his revolution takes place through air that is liquid and sweet.

“The power of the earth, both the celestial and terrestrial earth, they called Isis, because of the equality, which is the source of justice: but they call the moon the celestial earth, and the vegetative earth, on which we live, they call the terrestrial.

Pompeii Alexander mosaic

“Demeter has the same meaning among the Greeks as Isis amongs the Egyptians: and, again, Kore and Dionysus among the Greeks the same as Isis and Osiris among the Egyptians. Isis is that which nourishes and raises up the fruits of the earth; and Osiris among the Egyptians is that which supplies the fructifying power, which they propitiate with lamentations as it disappears into the earth in the sowing, and as it is consumed by us for food.

“Osiris is also taken for the river-power of the Nile: when, however, they signify the terrestrial earth, Osiris is taken as the fructifying power; but when the celestial, Osiris is the Nile, which they suppose to come down from heaven: this also they bewail, in order to propitiate the power when failing and becoming exhausted. And the Isis who, in the legends, is wedded to Osiris is the land of Egypt, and therefore she is made equal to him, and conceives, and produces the fruits; and on this account Osiris has been described by tradition as the husband of Isis, and her brother, and her son.

“At the city Elephantine there is an image worshipped, which in other respects is fashioned in the likeness of a man and sitting; it is of a blue colour, and has a ram's head, and a diadem bearing the horns of a goat, above which is a quoit-shaped circle. He sits with a vessel of clay beside him, on which he is moulding the figure of a man. And from having the face of a ram and the horns of a goat he indicates the conjunction of sun and moon in the sign of the Ram, while the colour of blue indicates that the moon in that conjunction brings rain.

“The second appearance of the moon is held sacred in the city of Apollo: and its symbol is a man with a hawk-like face, subduing with a hunting-spear Typhon in the likeness of a hippopotamus. The image is white in colour, the whiteness representing the illumination of the moon, and the hawk-like face the fact that it derives light and breath from the sun. For the hawk they consecrate to the sun, and make it their symbol of light and breath, because of its swift motion, and its soaring up on high, where the light is. And the hippopotamus represents, the Western sky, because of its swallowing up into itself the stars which traverse it.

“In this city Horus is worshipped as a god. But the city of Eileithyia worships the third appearance of the moon: and her statue is fashioned into a flying vulture, whose plumage consists of precious stones. And its likeness to a vulture signifies that the moon is what produces the winds: for they think that the vulture conceives from the wind, and declares that they are all hen birds.

“In the mysteries at Eleusis the hierophant is dressed up to represent the demiurge, and the torch-bearer the sun, the priest at the altar the moon, and the sacred herald Hermes.

“Moreover a man is admitted by the Egyptians among their objects of worship. For there is a village in Egypt called Anabis, in which a man is worshipped, and sacrifice offered to him, and the victims burned upon his altars: and after a little while he would eat the things that had been prepared for him as for a man.

“They did not, however, believe the animals to be gods, but regarded them as likenesses and symbols of gods; and this is shown by the fact that in many places oxen dedicated to the gods are sacrificed at their monthly festivals and in their religious services. For they consecrated oxen to the sun and moon.

“The ox called Mnevis which is dedicated to the sun in Heliopolis, is the largest of oxen, very black, chiefly because much sunshine blackens men's bodies. And its tail and all its body are covered with hair that bristles backwards unlike other cattle, just as the sun makes its course in the opposite direction to the heaven. Its testicles are very large, since desire is produced by heat, and the sun is said to fertilize nature.

Pompeii fresco of a water ceremony for the Egyptian goddess Isis

“To the moon they dedicated a bull which they call Apis, which also is more black than others, and bears symbols of sun and moon, because the light of the moon is from the sun. The blackness of his body is an emblem of the sun, and so is the beetle-like mark under his tongue; and the symbol of the moon is the semicircle, and the gibbous figure.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~\; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, "History of Art" by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~\; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, World Religions edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); History of Warfare by John Keegan (Vintage Books); History of Art by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018