MOSAICS

Antioch Mosaic Mosaics are pictures made from arrangements of small fragments of stone or glass. Among many ancient peoples they were the primary form of architectural decoration.

Mosaics date back to the dawn of civilization at Mesopotamia where architects used small colored objects to decorate the temples in Uruk in the forth millennium B.C. The Greeks and Romans used pebbles and shells to make pictorial composition around the forth century B.C. Early Greco-Roman artisans began making mosaics with pieces of colored glass broken off in different shapes from thin sheets baked in a kiln.

The Romans developed the mosaic as an art form, a tradition that was carried on by the Byzantines. Geraldine Fabrikant wrote in the New York Times, “Americans who amass new fortunes today race to cover their walls with art that proclaims their status, but the status symbols of ancient North Africa’s megawealthy lay literally at their feet. And aside from the prestige value, mosaic floors helped cool interior temperatures in an area of the globe that could be relentlessly hot.

Archaeologists have found mosaics not just in villa reception rooms, but also in dining rooms and bedrooms. Only the floors of the servants’ quarters were left bare. Although mosaics were occasionally created on walls, “the medium was really viewed as an efficient floor covering, waterproofed, durable and easy to walk on,” said another expert, Christine Kondoleon, a senior curator of Greek and Roman art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Categories with related articles in this website: Early Ancient Roman History (34 articles) factsanddetails.com; Later Ancient Roman History (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Life (39 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Art and Culture (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Government, Military, Infrastructure and Economics (42 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ;

“Outlines of Roman History” forumromanum.org; “The Private Life of the Romans” forumromanum.org|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu;

Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org

The Roman Empire in the 1st Century pbs.org/empires/romans;

The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ;

Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors roman-emperors.org;

British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;

Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art;

The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ;

Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu;

Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ;

History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame /web.archive.org ;

United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Roman Mosaics

The ancient Romans used mosaics mostly to decorate the floors of palaces and villas. Generally, only the wealthy could afford them. Some have also been found on public sidewalks, walls, ceilings and table tops and at public bathes. In some rich towns, it seemed as if every upper class house contained mosaic pavements. They decorated entrances, halls , dining rooms, corridors and sometimes the bottom of pools. Mosaics were often used to decorate dining rooms (and sometimes contained bits of discarded food). Usually frescoes were used adorned the walls.

Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University wrote for the BBC: “The floors of Roman buildings were often richly decorated with mosaics, many capturing scenes of history and everyday life. Some mosaics were bought 'off the shelf' as a standard design, while the wealthy villa owners could afford more personalised designs.” [Source: Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

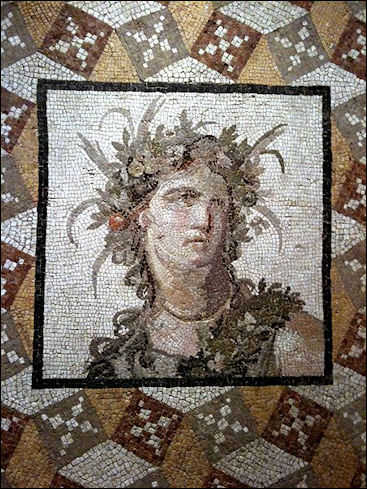

Mosaic from Tunisia's Bardo Museum Early Roman mosaics contained monochromatic designs. As the art form developed they used increasingly smaller pieces to create increasingly more elaborate designs in an increasingly wide variety of colors. The human figures have flesh tones, shading and musculature made with a wide variety of pebbles gathered from the sea and local quarries.

Roman mosaics were made mostly of finger-nail size stones, many of which were naturally colored. By contrast Byzantine mosaics were made with teensy-weensy tiles, and often contained a lot of gold and precious and semi-precious stones. It is no surprise then they were placed on walls, where people couldn’t walk on them.

To make a Roman mosaic: 1) A base was created with layered pieces of wooden planks, cut hay, porcelain, gravel, clay and mortar; 2) plasters was applied to the surface. 3) before the plaster hardened, stones or pieces of glass were placed in it. Large tiles or flat stones were placed around the edge of the mosaic. The designs were usually drawn on the surface.

Skilled mosaic artists learned their crafts at schools in Tunis and Alexandria. They often carried mosaic books to help their clients chose what patterns and designs they wanted. Sometimes they worked alone. Other times they worked with a team for a year or more.

Mosaics in Rome are found at Santa Costanza, Santa Pudenziana , Santi Cosma e Damiano, Santa Maria Maggiore, Santa Maria Dominica, San Zenone, Santa Cecilia (in Trastavere), Santa Maria (in Trastavere), San Clemente, and St. Paul's within the Walls (on via nazionale at via Napolu, down from Stazione Termini). Ancient Roman mosaics can also be seen in the Galleria Borghese and the Museo Nazionale Romano.

Making Mosaics

To create a Byzantine-style wall mosaic, Princeton University professor Kurt Weitzmann said, "a master artist, advised by a learned cleric concerning the theoretical accuracy of the subject matter, first sketched an entire scene. Assistants helped to design a series of cartoons; they determined the preliminary lines to be drawn on the wet plaster. Then in descending order of ability, the best mosaicists executed the heads of the figures, others filled in the details such as draped backgrounds, and still others the plain background. Since successful workshops depended on long traditions and complex skills, only great artistic centers could maintain them. For centuries Constantinople dominated the world of mosaic art."♪

Many mosaics are made from stone cubes about the size of dice. Herbert Kessler of John Hopkins wrote in Smithsonian: ""Course plaster laden with straw was troweled into the wall and over it; a smoother coat was spread in areas just large enough to finish before the bed hardened. Designs from carefully prepared cartoons were transferred to the wet surface, and them finally, the master mosaicists worked their magic creating flesh, cloth and feathers from stone and precious metals, and torrents of rain, smoke and sky from marble and glass. In some passages they used subtle tonalities to produce a subdued effects; elsewhere, they animated the surfaces with splashes of yellow, red and green. Throughout their comprehensive pictogram of decoration, however artistry and technical virtuosity knit an infinitely complex design into a cohesive whole.”

As Serat and the Pointillists later discovered, mosaic images made with fragments of pure color radiated power and intensity when viewed at the proper distance. This effect was intensified in Byzantine mosaics which were often made of highly reflective colored glass.

Pompeii Nilotic scene

Roman Mosaic Images

The images found Roman mosaics ranged from simple geometric designs to breathtaking complex picture. Some are amazing realistic. A mosaic from Pompeii showing Alexander the Great battling the Persians was made from 1.5 million different pieces, almost all of them cut individually for a specific place on the picture.

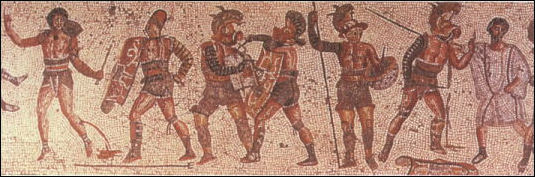

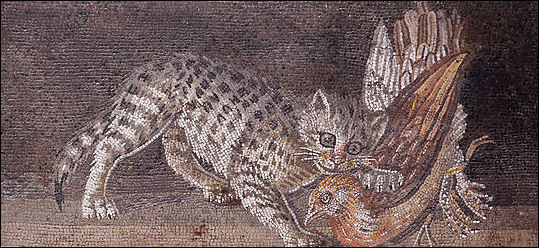

Typical Roman mosaics contained battles scenes with charging cavalries, mythical scenes with romping gods and goddesses, accompanied by nymphs and satyr, still-lifes of seashells, nuts, fruit vegetables and advancing mice and gladiators. Mosaics uncovered at a 1600-year-old Roman villa near the Sicilian town of Piazza Armerina showed women in bikinis exercising with dumbbells. In Pompeii "beware of dog" signs were turned into elaborate mosaics.

Many scholars believe the best mosaics were made in the provinces of North Africa. Portrait of Neptune, made by an anonymous artist in the 2nd century A.D., found on coast of Tunisia is believed to be one of the best.

The mosaic depicting Alexander the Great's defeat of the Persian king Darius, now in the Naples Museum, is one of the most famous ancient mosaics. Dr Joanne Berry wrote for the BBC: “In its entirety the mosaic measures 5.82 x 3.13m (19ft x 10f3in), and is made of around a million tesserae (small mosaic tiles). It was discovered in the largest house in Pompeii, the House of the Faun, in a room overlooking the central peristyle garden of the house. It is thought that this house was built shortly after the Roman conquest of Pompeii, and is likely to have been the residence of one of Pompeii's new, Roman, ruling class. The mosaic highlights the wealth and power of the occupier of the house, since such grand and elaborate mosaics are extremely rare, both in Pompeii and in the wider Roman world.” [Source: Dr Joanne Berry, Pompeii Images, BBC, February 17, 2011|]

Roman Floor Mosaics with Violent Scenes

In 2016, the Getty Villa museum in Los Angeles hosted an exhibition of mosaics in which an overarching theme seemed to be bloody violence. Christopher Knight wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “One floor mosaic shows three hunters with staffs herding five fearsome bears into a giant net strung up between two trees. The beasts turn, growl and gnash their teeth. Another displays the moment when a muscled and victorious boxer, having just taken out his equally muscled human opponent, lays flat a great horned bull — just in case anyone doubted his superior strength and power. A gash by the staggered bull's eye tells the tale, echoing the blood running from the vanquished boxer's head. [Source: Christopher Knight, Los Angeles Times, April 13, 2016]

“A third features a lion chomping on the back of an onager — a wild ass — that has just been felled. The cat's big claws make a gory mess of things. The onager swivels his anguished head and meets the lion's ferocious gaze, while blood streams on the ground in a cluster of zigzag lines like jagged bolts of lightning. Is it any wonder Roman soldiers applied the name onager to the mechanical catapult they used for besieging walled compounds? The recoil when the war machine was sprung reminded them of the wild beast's violent kick.

“Here's the odd thing: Most of these rough and tumble floor mosaics of brutal combat were made as decorative embellishments for the lavish villas of the wealthy elite — an entrance hall, say, or a dining room. A couple were designed for more public sites, such as the baths that were part of regular leisure rituals and social contact. Mural-painted walls are one thing, but a durable stone floor is quite another. A mosaic, composed of thousands of small bits of hand-set stone and glass, is not easy to make. Nor is it inexpensive, nor easy to change.

Gladiators from the Zliten mosaic

“At 28 feet wide — and then still just a fragment of the full floor — the bear hunt mosaic from a villa outside Naples, Italy, was plainly designed to impress. (The remainder of the mosaic is in Naples' National Archaeological Museum.) Tesserae — flat, irregularly shaped stone bits — are pieced together in shades of white, gray, pink, purple, ochre, umber and black to create a surprisingly nuanced drawing.

“The action scene at the center is surrounded by tesserae fashioned as decorative braiding. There are also laurel festoons, various animals (real and imaginary), assorted fruits, some cupids and sizable ornamental heads backed by elaborate acanthus leaves at the corners, perhaps personifications of the four seasons. The fierce bear hunt is woven into cycles of nature and rituals of culture, all as lavish decoration.

“Combat chic seems to have been a way for the wealthy elite to revel in — and show off — their worldly success. They have triumphed over life's harsh vicissitudes. Images of conflict are metaphors for the battles they or their families fought, and not just militarily, to get where they are. Put under foot, they adorn the very foundation of things.

“Scholars are not certain, but the bear-hunt floor is thought to have come from an upscale civic bath house. Enjoy your relaxing visit, the Neapolitan bath décor would seem to say; you've earned it.

“But sometimes, a dazzling design of sophisticated stylishness absorbs ferocity into its sumptuous pattern. Perhaps the most viscerally stunning mosaic is on the catalog's cover — a delicately colored head of the Gorgon Medusa, she with the hairdo of writhing snakes. The monster could turn an enemy to stone with just a glance.

“Medusa's bust is set within a medallion at the center of a dramatic, spiraling whorl of black and white triangles, a pulsing visual vortex that animates the twisting nest of snakes crowning her head. The circular design is like a shield.

“Perhaps it's the one that Athena carried after the Gorgon was slain, with Medusa's still-powerful head attached to the shield's front for protection. Even severed, Medusa's head was a weapon. The chic mosaic is gorgeous.

Roman Mosaics in Tunisia

Museums under the control of the Institut National du Patrimoine in Tunisia — particularly the El Jem Museum in northeast Tunisia — possess some of the world’s finest Roman-era mosaics. Many have been unearthed over the last 200 years and carefully preserved in Tunisia’s museums with the help of the Getty Museum. [Source: Geraldine Fabrikant, New York Times, April 11, 2007]

Mosaic from Tunisia's Bardo Museum

Describing an A.D. 4th century mosaic discovered in 1974 in Kelibia (now in northeastern Tunisia), Geraldine Fabrikant wrote in the New York Times, Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, sits gazing languorously at herself in the river after a musical solo on an aulos, an ancient double-reed pipe. The river itself is symbolized by an elderly yet muscular man sitting across from her. Athena looks vaguely unhappy, perhaps because the constant playing, which involved using her mouth as a kind of bagpipe, has distorted the shape of her lips...In the ancient mythological tale, she threw the instrument on the ground in anger. The satyr Marsyas, depicted in the right-hand corner of this mosaic, picked it up and challenged Apollo to a competition. Infuriated by his arrogance, Apollo had Marsyas flayed.

In other works: “Muscular gods ride chariots drawn by superb sea horses; voluptuous, half-nude women pour jugs of water down their own backs. Rabbits eagerly nibble grapes, and ferocious lions devour their prey. The panoply of tales told in stone sheds some light on how a wealthy Roman elite lived in North Africa between the second and sixth centuries.

Despite the obsessive focus on Rome, experts say, the mosaics were also molded by the African experience. They were more colorful and exuberant than other mosaics of that period because of the stones in the area, Ms. Kondoleon said. If North Africans were eager to show off their knowledge of Rome, there was a highly practical incentive. Aicha Ben Abed, a scholar at the Tunisian institute, writes in the book “Tunisian Mosaics: Treasures From Roman Africa” that a legal statute compensated citizens on the basis of how well they adhered to the values of Roman civilization. Cities that complied most admirably were treated as colonies, which meant that their denizens had the same rights as Roman citizens.

A third-century mosaic depicting two lions ferociously tearing apart a boar was found in the dining room of a home in El Jem, inland in southern Tunisia. That same room also revealed a nine-foot-long floor portrait of a procession with Bacchus as its centerpiece. In Roman mythology, Bacchus, the god of wine and fertility, was thought capable of subduing the forces of nature and wild animals. The lions devouring the boar have fierce paws but somewhat human faces, characteristic of animals in mosaics from that part of the world.

Kris Kelly, a senior curator at the Getty, said that North African mosaics tended to be more colorful than those from other parts of the Roman Empire because the terrain yielded a wider variety of colored stones and glass. The works also reflect the region’s focus on sea fishing along the coast, and hunting and agriculture further inland. A 5-by-7-foot mosaic of Neptune driving two horses while holding his trident was found in 1904 in the coastal city of Sousse; an imposing head of Oceanus, with lobster claws darting from his hair and dolphins swimming out of his beard, was discovered in 1953 in the baths of Chott Merien, another Mediterranean port.

Roman Mosaics in Turkey

The Hatay Archeological Museum in Antakya, Turkey has an impressive collection of Roman mosaics. Unlike Byzantine mosaics which were put on walls and made of teensy-weensy tiles, Roman mosaics were placed on floors and made of finger-nail size stones, many of which are naturally colored. The mosaic museum contains what is regarded as the world’s second finest collection of Roman mosaics after the mosaic museums of Tunisia

The mosaics at the museum in Antakya were taken from villas owned by wealthy merchants. The art became so developed here that a mosaic school was opened. A Turkish archeologist wrote, “In the whole area there was not a single better-class house without mosaic pavements decorating its enhance, halls , dining rooms, corridors and sometimes the bottom of pools.”

More than 100 mosaics are on display. Some depict everyday Roman life and scenes from mythology. Others feature geometric designs or natural patterns. The human figures have flesh tones, shading and musculature made with a wide variety of pebbles gathered from the sea and local quarries. One if the most famous mosaics at the museum, from the A.D. 4th century, shows a bearded Oceanus with crab claws coming out of his head, with Thetis with wings coming out her head. The heads are surrounded by colorful fish and cherubs .

Other impressive mosaic images include Clytemnestra beckoning her daughter Iphigenia; a drunken Dionysus helping a satyr; Hercules with head of an adult and the body of an infant; and an evil eye being attacked by a scorpion. The mosaics are in good condition and survived the earthquakes because they were on the floor. The largest is 600 square feet and can be observed from a balcony. The scenes from daily life have helped historians grasp what life was like in Roman times.

The museum’s chief archeologist told the New York Times, “One reason the mosaics made in this region are so extraordinary is that so much attention was given to collecting pebbles for them. As the art developed, smaller and smaller pebbles were used, and they were cut into finer and finer shapes. The shading on some of these works is amazing. You get a sense of perspective and expression. These are some of the finest artistic quality works of all antiquity.”

Villa Romana La Olmeda

The mosaic artists traveled to Tunis and Alexandria to learn techniques and carried mosaic books to help their clients chose what patterns and designs they wanted. Sometimes they worked alone. Other times they worked with a team for a year or more. The museum has so many of their masterpieces that many of them are in storage. Many more are hidden under the dirt or buildings scattered around town.

Mosaics in Zeugma, Turkey

Kutalmis Gorkay of Ankara University, has directed work at Zeugma, an ancient Roman border town being submerged by a dam and reservoir in southeast Turkey, since 2005. Many of the mosaics found in courtyards of the elite have water themes: Eros riding a dolphin; Danae and Perseus being rescued by fishermen on the shores of Seriphos; Poseidon, the god of the sea; and other water deities and sea creatures. [Source: Matthew Brunwasser, Archaeology, October 14, 2012]

Matthew Brunwasser wrote in Archaeology magazine: According to Gorkay, the mosaics were an important part of a house’s mood, and their function went far beyond the strictly decorative. Many of the mosaics were selected according to a room’s function. For example, bedrooms sometimes featured lovers’ stories, such as that of Eros and Telete. The choice of images in the mosaics also reflected the owner’s taste and intellectual interests. “They were a product of the patron’s imagination. It wasn’t like simply choosing from a c atalog. They thought of specific scenes in order to make a specific impression,” he explains. “For example, if you were of the intellectual level to discuss literature, then you might select a scene like the three muses,” Gorkay says. The muses were thought to be the inspirations for literature, science, and the arts. “They are also a personification of good times. When people drank near this mosaic, the muses were always there, accompanying them for atmosphere,” he says. [Source: Matthew Brunwasser, Archaeology, October 14, 2012]

“Other popular themes in these reception and dining areas were love, wine, and the god Dionysus. However, it was not only subject matter that was important in choosing the mosaics. It was also their placement. “In a dining room off a courtyard, the couches on which people were sitting or lying, drinking, and having parties were positioned around the mosaics so people could see them, as well as the courtyard and pool,” Gorkay says. He also explains that there was an order in which the mosaics were intended to be viewed. When guests first entered the house, there was a salutory mosaic positioned to make an impression on people coming through the doorway. This mosaic might give introductory hints to the guests about the favorite subjects, taste, or themes of the host. In the next room, they were invited to recline on couches in order to view other mosaics. After the guests were seated, the convivium, or feast, would begin.”

Mine Yar, with the Istanbul-based Art Restorasyon, has been excavated and restoring mosaics at Zeugma. “While doing restoration work, Yar noticed that sections of tesserae had been replaced in three mosaics, one featuring the three muses, a second showing the goddess of the earth, Gaea, and a third geometric mosaic that once covered a pool. “Maybe the lady of the house wanted to redecorate,” she says. She also detected other irregularities in a geometric mosaic where stones were used irregularly to fill cracks or holes, indicating that the emblema had been changed, although what the original depicted remains unknown. During the rescue work Kucuk says the team learned about how the mosaics had been made. “We found drawings underneath the mosaics showing the ancient workers where to place the panels,” he explains. “This helped us understand that mosaic panels were not put together inside the house. Instead, they made them in the workplace and then brought the finished mosaic to the home in pieces and placed it, section by section, on the floor.”“

“Be Cheerful” Mosaic Found in Southern Turkey

In 2016, hurriyetdailynews.co reported: “What could be considered an ancient motivational meme which reads “be cheerful, live your life” in ancient Greek has been discovered on a centuries-old mosaic found during excavation works in the southern province of Hatay. Demet Kara, an archaeologist from the Hatay Archaeology Museum, said the mosaic, which was called the “skeleton mosaic,” belonged to the dining room of a house from the 3rd century B.C., as new findings have been unearthed in the ancient city of Antiocheia. [Source: hurriyetdailynews.com, Ancientfoods, July 5, 2016]

““There are three scenes on glass mosaics made of black tiles. Two things are very important among the elite class in the Roman period in terms of social activities: The first is the bath and the second is dinner. In the first scene, a black person throws fire. That symbolizes the bath. In the middle scene, there is a sundial and a young clothed man running towards it with a bare-headed butler behind. The sundial is between 9 p.m. and 10 p.m. 9 p.m. is the bath time in the Roman period. He has to arrive at supper at 10 p.m. Unless he can, it is not well received. There is writing on the scene that reads he is late for supper and writing about time on the other. In the last scene, there is a reckless skeleton with a drinking pot in his hand along with bread and a wine pot. The writing on it reads ‘be cheerful and live your life,’” Kara explained.

“Kara added the mosaic was a unique finding for the country. “[This is] a unique mosaic in Turkey. There is a similar mosaic in Italy but this one is much more comprehensive. It is important for the fact that it dates back to the 3rd century B.C.,” Kara said. She also said that Antiocheia was the world’s third largest city in the Roman era, and continued: “Antiocheia was a very important, rich city. There were mosaic schools and mints in the city. The ancient city of Zeugma in [the southeastern province of] Gaziantep might have been established by people who were trained here. Antiocheia mosaics are world famous.”

Mosaics from Britain

Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University wrote for the BBC: Some of the finest Roman mosaics in Britain can be seen at Fishbourne Roman Palace and Bignor Roman Villa. Situated near Chichester, the luxurious establishment at Fishbourne went through several phases of construction. This floor was laid in the early 3rd century and the panel, with a centrepiece of a cupid and dolphin, measures approximately 17 ft by 17 ft. Sea-horses and sea-panthers surround the central medallion of a cupid astride a dolphin. [Source: Dr Nigel Pollard of Swansea University, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

A Head of Medusa can be seen at Bignor Roman Villa, Sussex. “In Greek mythology, Medusa was usually depicted with hair consisting of snakes. She was the only mortal Gorgon and was killed by Perseus who cut off her head. Her severed head could turn those who looked at it into stone. The Trojan prince Ganymede is carried off by an eagle to be a cup-bearer to the gods on Mount Olympus. The room containing this mosaic had underfloor heating and was probably used as a winter dining-room. Local materials were often used to make mosaics. Sandstone would produce yellow, orange and red mosaics whilst chalk and limestone were used for white and Purbeck marble for grey or blue. |::|

The “Venus” at Bignor Roman Villa, “recognised as one of the finest in Britain, is usually identified as Venus, although it may have been the head of a mere mortal, perhaps based on the lady of the house. The image is flanked by long-tailed birds and winged cupids dressed as gladiators Green glass is used in the birds and fern leaves. The secutor (a kind of gladiator) traditionally carried a shield and sword and wore a helmet with visor, leg guards and a breast-plate. This gladiator is part of a long panel filled with winged cupids dressed as gladiators. A rudarius (umpire) holds a rudus (wand of office) as he watches a secutor and retarius fight. |::|

Pompeii Vagrant musicians

Byzantine Mosaics

Wall mosaics began to catch on in the late Roman period but it was the Byzantines who raised mosaics to expression of high art. Romans built mosaic floors while Christians made mosaic ceilings and upper walls to glorify God and heaven. Many Byzantine mosaics have a gold background.

The Byzantines (Christianized Romans and Greeks) dominated eastern Europe and Asia Minor from the A.D. 4th century to the 15th century. Their mosaics were made to both dazzle and instruct the people who came to the church, the majority of whom were illiterate. The exterior of the churches that housed the mosaics were usually drab and monolithic.

"A symphony of shapes and symbols," wrote Robert Wernick in Smithsonian magazine, "was to conduct the eye toward the triumphant truth of revealed religion. Truth was overhead in the rounded ceilings of domes and apses, in the from of a golden cross in a starry sky, a Virgin and Child, a mystic lamb, a baptisms in the Jordan. On the walls below, drawing the eye upward, were scenes from the Old Testament — the sacrifices of Abel and Melchizedek, the visions of Moses and Elijah — prefiguring the coming of Christ; scenes from the New testament confirming the prophecies of the Old: processions, rituals, saints, martyrs, birds and beats and flowers."

The Byzantine art of mosaic making reached its zenith in A.D. 5th century Ravenna, where artisans used 300 different shaded of colored glass — broken into square, oblong, teassarae and irregular shapes — to composed pictures of landscapes, battle scenes, abstract geometrical patterns and religion and mythical scenes.

We know virtually nothing about the artisans who created the great Byzantine mosaic masterpieces. they didn't sign their names and scholars are not even sure whether they were Romans or Greeks.

Mosaic Archeology

Although scholars are well versed in the ancient myths animating the mosaics, they are unsure how much of the actual work was done on site. Ms. Ben Abed says that only a single bas-relief from ancient Roman culture, found in ancient Ostia, depicts a mosaic workshop. In Thuborbo Majus archaeologists found a trove of stone chips and tesserae that made it clear that mosaics were laid on site there. [Source: Geraldine Fabrikant, New York Times, April 11, 2007]

Organizing and shipping mosaics is a challenge. For an an exhibit of Tunisian mosaics at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the mosaics were taken to Carthage, then shipped by boat to Marseille. From there, they were taken by truck to an airport and flown to Los Angeles. Upon arrival at the Getty Villa in Malibu the mosaics were cleaned.

Pompeii Cat and birds

Archaeologists emphasize the importance of leaving mosaics in situ so that scholars can consider the role each played in the society where it existed. Maintaining Tunisian mosaics in situ is hardly an easy task, given that so many are exposed to the elements in largely undeveloped areas. In some cases workers have had to rebury mosaics to protect them from the elements until conservation is possible.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~\; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018