ANCIENT ROMAN SCULPTURE

Heroic statue of Augustus While the Greeks made sculptures of idealized human forms, the Roman tended to make portraits. Romans made sculptures of gods, heroes, emperors, generals and politicians. They also used sculpted images to adorn the capitals of columns and the helmets of gladiators. Roman sculptures often reflected the fashions and lifestyles that were prevalent when they were made. Archaeologists can even date sculptures of Roman by their hairdos and clothing styles. During the Augustan Age, for example, women parted their hair in the middle with a central roll. The Flauvians and Antiones had more elaborate coiffures that resembled a honeycomb of curls. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Sculpture were made spectacular-looking but hard to work stone such as porphyry from Gebel Dokhan in northeast Egypt, basanite granite from Gebel Fatireh in eastern Egypt, and blue, yellow, green, black and grey marble from elsewhere in the empire.

Categories with related articles in this website: Early Ancient Roman History (34 articles) factsanddetails.com; Later Ancient Roman History (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Life (39 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Art and Culture (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Government, Military, Infrastructure and Economics (42 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ;

“Outlines of Roman History” forumromanum.org; “The Private Life of the Romans” forumromanum.org|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu;

Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org

The Roman Empire in the 1st Century pbs.org/empires/romans;

The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ;

Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors roman-emperors.org;

British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;

Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art;

The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ;

Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu;

Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ;

History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame /web.archive.org ;

United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Greek Versus Roman Sculpture

Roman sculpture regressed from Greek sculpture back to images that seemed rigid and frozen in space. Romans liked to put copies of Greek sculptures in their gardens and homes as decorations and works of art. Historian Daniel Boorstin wrote in “The Creators”, “While the Greeks gave their gods and ideal humans form the Romans attempted to make their ruler godlike." The Romans also recognized the need to humanize their subjects, and thus Nero was given same baby fat and Hadrian was made majestic. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

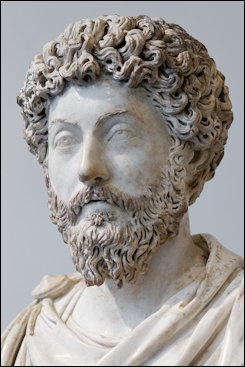

The main difference between Greek and Roman sculpture was the later was more personalized. Greeks statues were of idealized human forms of athletes and gods while Roman statues depicted real people — primarily people important enough to have an image of them commissioned, or wealthy enough to afford their own, There are few examples or ordinary people. All Roman emperors had their statues publicly displayed and statues of Marcus Aurelius, Caesar, and Vespasian all exist today. These statues obviously were intended to portray the leaders in the best light and ended up looking like the equivalent of modern-day blown dry images of politicians. The most revealing and skilled works are busts done of ordinary Romans and Arabs, but even their facial features and wrinkles were often used covey the intent of the sculptor not necessarily depict a real life person. [Source: “History of Art” by H.W. Janson, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.]

Sculpture, Death and Immortality in Ancient Rome

Equestrian statue

of Marcus Aurelius

When the leader of the household died, a waxen image was made of his head and placed in a shrine on the family altar. During funerals these images were pulled out and carried in a procession. Later they were sculpted from marble because the wax only lasted for a few decades. [Source: "History of Art" by H.W. Janson, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.]

"Is there anyone," Polybius (205-125 B.C.) wrote, "who would not be edified by seeing these portraits of men reknown for their excellence and by having them all present as if they were living and breathing? Is there anything which is more ennobling than this?...thereby not allowing human appearances to be forgotten nor the dust of ages to prevail against men." ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

After a funeral, the family of the deceased nobleman painted a wax death mask of the nobleman on a bust which in turn was placed in the most prominent place in the house. Later on the bust was placed on a shelf in the atrium with likenesses of other deceased relatives, all of whom were connected by colored lines that assembled them into a genealogical chart. During some festivals a crown of bay leaves was placed on the bust and during family funerals people wore the masks during the procession. [Ibid]

The intent of Roman sculpture was to immortalize the people who were sculpted and artists attempted to capture a likeness of the individual. Greek sculpture on the other hand were of idealized humans. The masks of Roman actors were made to look like the people the actors were playing. [Ibid]

Destroying a statue carried the same meaning as destroying the existence of a person. "If statues could perpetuate memory," Boorstin wrote, “destroying them could erase memory...In addition to execution and confiscation of property the [name] of the condemned could not be perpetuated in his family, images of him were to be destroyed, and his name was supposed to be erased from all inscriptions. the only way the accused could escape these indignities was by committing suicide before the charges were officially lodged." The wife of condemned emperor had a sculpture secretly made after his death. To accomplish this the sculptures had to reassemble the emperor's dismembered body." [Ibid]

Mass Produced Sculptures in Ancient Rome

Bronze statues were made using the lost wax technique in which wax was used to make a clay mold. They were often embellished with silver or stone eyes, teeth and nails and copper eyelashes and nipples. Few bronze sculptures remain, most were melted down to make weapons, kitchen utensils or other items.

Many Greco-Roman sculptures that were thought to be masterpieces it turns were actually massed produced using assembly line methods for gardens. It was originally thought that large statues were made in a single piece but later it was discovered that they made from pre-caste parts joined together. Evidence that was so includes X-ray photographs that show details on how early statue parts were joined and flaws were hammered out; chemical analysis indicated that lead was added to save money on bronze.

A 1,500-year-old earthenware vase that was one thought showed of human dismemberment actually depicted an ancient bronze statue assembly line.

Aphrodisias Sculpting School

Aphrodisias (a two or three hour taxi or mini-bus day trip away from Pamukkale and Ephesus) in Turkey was an ancient city dedicated to Aphrodite, goddess of love and fertility and the home of a famous sculpture school.. It rose to prominence in 88 B.C. and reached its peak as a Roman city during the first and second centuries A.D.

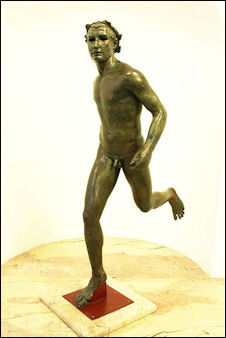

Greek statue of a runner People had lived at the site since 5800 B.C.. The Greco-Roman acropolis was built on the remains of the tribals communities that lived here before the Greeks arived in the 6th century B.C. and the Romans took it over in the 1st century B.C. and it thrived as a religious and cultural center and tax-free tarding haven. Aroudn the 5th century it became the Byzantine city of Stavropolis. [Archeology Magazine January/February 1990; Dora Jane Hamblin, Smithsonian, Kena T. Erim, National Geographic, June 1972].

The Aphrodisias Sculpting School was one of the most famous sculpting school in antiquity. Among the provocative pieces preserved today are statues of Aphrodite cradling a child like a loving mother; Hercules rippling his muscles; and a woman weeping, which symbolized the subjugation of the city by Rome. Any rich noblemen who donated money to the school was honored with a statue, and there are plenty of these, as well as some magnificent friezes and sarcophagi, in the museum.

The Aphrodisias sculpting school thrived for 600 years, and the high-quality marble for the sculptures was found in abundance in quarries only a few miles away. The sculptors, some scholars claim, were the world's the first true artists, meaning they didn't just copy other statues like many Greek and Roman sculptors; instead they made unique creations. held up balconies and stairs.

Aphrodisias is situated among dry, scrubby mountains at an elevation of 2000 feet. Among the treasures unearther here are a lion and snake mosaic and an impressive array of statues of figures from Greco-Roman mythology, centaurs, Trojan heroes and Roman emperors. There is so much stuff that expressions like an “an embarrassment of riches” has used to describe the throve, which far exceeds what the museum can hold.

In ancient times the public buildings were adorned with friezes and statues. The Roman Baths that can be seen today had three pools: the “frigidarium” , the “teoidarium” and the scalding “calidarium” heated by furnaces stoked by slaves. Next door to the baths in the palaetras (essentially a health club), wealthy Romans jogged, lifted weights and played handball. After their workout was over they were oiled, perfumed and massaged. The Maeander River, the source of word “meander,” lies nearby and prvoded water for the baths.

In the 8000-seat marble amphitheater, audiences watched masked and robed actors perform dramas about conspiring slaves and two-timing wives. When the show was over the audience was discouraged out of a gate called the “vomitorium” . In the 760 foot long hippodrome, one of the longest ever uncovered, spectators cheered gladiators as they battled with wolves and bears and watched chariots flip up on one wheel as they careened around the sharp curves. In the agora shoppers bought goods with prices set by the Roman government. In the Temple of Aphrodite, women prostituted themselves and cut off all their hair to honor the Greek goddess. The temples was built around the 1st century B.C. and turned int a Christian basilica in the A.D. 5th century. Today you can see some collapsed walls and 14 standing Corinthian columns.

Contexts for the Display of Ancient Roman Statues

Roman statues of runners

found at Herculaneum “According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the early Roman Republic, the principal types of statue display were divinities enshrined in temples and other images of gods taken as spoils of war from the neighboring communities that Rome fought in battle. The latter were exhibited in public spaces alongside commemorative portraits. Roman portraiture yielded two major sculptural innovations: "verism" and the portrait bust. Both probably had their origins in the funerary practices of the Roman nobility, who displayed death masks of their ancestors at home in their atria and paraded them through the city on holidays. Initially, only elected officials and former elected officials were allowed the honor of having their portrait statues occupy public spaces. As is clear from many of the inscriptions accompanying portrait statues, which assert that they should be erected in prominent places, location was of crucial importance. Civic buildings such as council houses and public libraries were enviable locations for display. Statues of the most esteemed individuals were on view by the rostra or speaker's platform in the Roman Forum. In addition to contemporary statesmen, the subjects of Roman portraiture also included great men of the past, philosophers and writers, and mythological figures associated with particular sites.” [Source: Marden Nichols, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

““Beginning in the third century B.C., victorious Roman generals during the conquest of Magna Graecia (present-day southern Italy and Sicily) and the Greek East brought back with them not just works of art, but also exposure to elaborate Hellenistic architectural environments, which they desired to emulate. If granted a triumph by the senate, generals constructed and consecrated public buildings to commemorate their conquests and house the spoils. By the late Republic, statues adorned basilicas, sanctuaries and shrines, temples, theaters, and baths. As individuals became increasingly enriched through the process of conquest and empire, statues also became an important means of conveying wealth and sophistication in the private sphere: sculptural displays filled the gardens and porticoes of urban houses and country villas. The fantastical vistas depicted in luxurious domestic wall paintings included images of statues as well. \^/

Livia, August's wife

““After the transition from republic to empire, the opportunity to undertake large-scale public building projects in the city of Rome was all but limited to members of the imperial family. Augustus, however, initiated a program of construction that created many more locations for the display of statues. In the Forum of Augustus, the historical heroes of the Republic appeared alongside representations of Augustus and his human, legendary, and divine ancestors. Augustus publicized his own image to an extent previously unimaginable, through official portrait statues and busts, as well as images on coins. Statues of Augustus and the subsequent emperors were copied and exhibited throughout the empire. Wealthy citizens incorporated features of imperial portraiture into statues of themselves. Roman governors were honored by portrait statues in provincial cities and sanctuaries. The most numerous and finely crafted portraits that survive from the imperial period, however, portray the emperors and their families. \^/

““Summoning up the image of a "forest" of statues or a second "population" within the city, the sheer number of statues on display in imperial Rome dwarfs anything seen before or since. Many of the types of statues used in Roman decoration are familiar from the Greek and Hellenistic past: these include portraits of Hellenistic kings and Greek intellectuals, as well as so-called ideal or idealizing figures that represent divinities, mythological figures, heroes, and athletes. The relationship of such statues to Greek models varies from work to work. A number of those displayed in prestigious locations in Rome were transplanted Greek masterpieces, such as the Venus sculpted by Praxiteles in the fourth century B.C. for the inhabitants of the Greek island of Cos, which was set up in Rome's Temple of Peace, a museumlike structure set aside for the display of art. More often, however, the relationship to an original is one of either close copying or eclectic and inventive adaptation. Some of these copies and adaptations were genuine imports, but many others were made locally by foreign, mainly Greek, craftsmen. A means of display highly characteristic of the Roman empire was the arrangement of statues in tiers of niches adorning public buildings, including baths, theaters, and amphitheaters. Several of the most impressive surviving statuary displays come from ornamental facades constructed in the Eastern provinces (Library of Celsus, Ephesus, Turkey). Bolstered by wealth drawn from around the Mediterranean, the imperial families established their own palace culture that was later emulated by kings and emperors throughout Europe. Exemplary of the lavish sculptural displays that decorated imperial residences is the statuary spectacle inside a cave employed as a summer dining room of the palace of Tiberius at Sperlonga, on the southern coast of Italy. Visitors to this cave were confronted with a panoramic view of groups of full-scale statues reenacting episodes from Odysseus' legendary travels.” \^/

Polychromy of Roman Marble Sculpture

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “When Roman marble sculpture was rediscovered in the Renaissance, it emerged from more than a millennium of burial essentially devoid of its ancient polychromy. The monochromatic appearance of these works gave rise to new, modern canons of sculpture characterized by an emphasis on form with little consideration of color. In antiquity, however, Greek and Roman sculpture was originally richly embellished with colorful painting, gilding, silvering, and inlay. Such polychromy, which was integral to the meaning and immediacy of such works, has largely been lost in burial and survives today only in fragmentary condition. [Source: Mark B. Abbe, Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation, Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

Emperor Diocletien “Depictions of statuary in Roman wall paintings provide an indication of their diverse appearances in antiquity. Some marble sculptures were completely painted and gilded, effectively obscuring the marble surface; others had more limited, selective polychromy used to emphasize details such as the hair, eyes, and lips and accompanying attributes. \^/

“Roman artists used a wide range of pigments, painting media, and surface applications to embellish their marble sculptures. Ancient authors, especially Pliny the Elder and Vitruvius, provide important information about these materials and express great admiration for the virtuoso technique of contemporary sculptors who developed a technical refinement unparalleled in classical antiquity. White marble itself was prized for its brilliant translucency, ability to take finely carved detail, and flawless uniformity. A vast array of colored marbles and other stones were also quarried from throughout the Roman world to create numerous colorful statues of often dazzling appearance. \^/

“Burial, early modern restoration practices, and historic cleaning methods have all reduced the polychromy on Roman marble sculptures. Many works, however, preserve important evidence of their original polychrome decoration. Such remains are inevitably fragmentary and have altered over time, making it difficult to reconstruct their exact appearance in antiquity with certainty. Nevertheless, through a host of techniques—including microscopic examination, ultraviolet and infrared photography, and different types of material analysis—it is possible to gain valuable insight into the original appearance of these ancient works of art.

Roman Copies of Greek Statues

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In the late fourth century B.C., the Romans initiated a policy of expansion that in 300 years made them the masters of the Mediterranean world. Impressed by the wealth, culture, and beauty of the Greek cities, victorious generals returned to Rome with booty that included works of art in all media. Soon, educated and wealthy Romans desired works of art that evoked Greek culture. To meet this demand, Greek and Roman artists created marble and bronze copies of the famous Greek statues. Molds taken from the original sculptures were used to make plaster casts that could be shipped to workshops anywhere in the Roman empire, where they were then replicated in marble or bronze. Artists used hollow plaster casts to produce bronze replicas. Solid plaster casts with numerous points of measurement were used for marble copies. Since copies in marble lack the tensile strength of bronze, they required struts or supports, which were often carved in the form of tree trunks, figures, or other kinds of images. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

Roman copy of a 4th century Greek statue of Artemis

“Although many Roman sculptures are purely Roman in their conception, others are carefully measured, exact copies of Greek statues, or variants of Greek prototypes adapted to the taste of the Roman patron. Some Roman sculptures are a pastiche of more than one Greek original, others combine the image of a Greek god or athlete with a Roman portrait head. The meaning of the original Greek statue often lent beauty, importance, or a heroic quality to the person portrayed. By the second century A.D., the demand for copies of Greek statues was enormous—besides their domestic popularity, the numerous public monuments, theaters, and public baths throughout the Roman empire were decorated with niches filled with marble and bronze statuary. \^/

“Since most ancient bronze statues have been lost or were melted down to reuse the valuable metal, Roman copies in marble and bronze often provide our primary visual evidence of masterpieces by famous Greek sculptors.” \^/

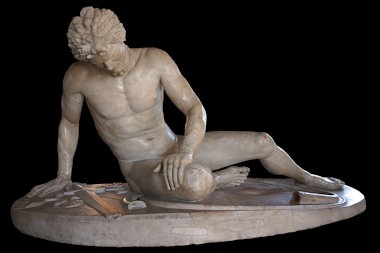

Dying Gaul

The “Dying Gaul,” is one of the most famous and most copied ancient Roman sculpture. Created in the A.D. first or second century, the larger-than-life-size statue is likely a Roman replica of an earlier Greek bronze. It has only left Italy twice: in 1797, when Napoleonic forces took the sculpture to Paris, where it was displayed at the Louvre until its return to Rome in 1816, and 2013, when it was exhibited at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Philip Kennicott wrote in the Washington Post: “There are few statues more celebrated than the Dying Gaul, and even fewer that can equal its emotional power. It depicts a young man with thick, matted hair, lying on the ground, supporting his slightly turned torso with a muscular right arm. A small slit in his chest and a few drops of gore tell us he is dying, and many people see on his downturned face a look of stoic pain. For many years after the statue was discovered early in the 17th century, the figure was identified as a dying gladiator. But various clues, including a tight-fitting necklace or torque and references in Pliny the Elder (the Roman author) to statues depicting the defeated Gauls, lead most scholars to conclude that he is a member of the far-flung tribe that harassed Mediterranean empires from the Greeks to the Romans. [Source: Philip Kennicott, Washington Post, December 12, 2013. Philip Kennicott is the Pulitzer Prize-winning Art and Architecture Critic of The Washington Post]

“The Greek original, if the scholarly consensus is correct, was installed in a sanctuary devoted to Athena, in the small but ambitious kingdom of Pergamum (now in Turkey) sometime in the third century B.C. The Attalid kings of Pergamum were a bunch of industrious nobodies who managed to lay claim to a shard of Alexander the Great’s vast but short-lived empire. Rather like the Gulf Arab states today, they used art to build up their international prestige, and Pergamum became a wonder of bombastic architectural excess. They were later absorbed into Rome, but not before defining what is still called the Pergamene Style, which emphasized emotional appeal and almost Baroque volatility. Nothing defines that style quite as clearly as the Dying Gaul, who is both tragic and sensual, firing both our desire and our sense of compassion.

Dying Gaul

“Almost every book on ancient sculpture includes a photograph of the statue, which is held by the Capitoline Museum in Rome. But photographs give a minimal sense of the work. The young man’s posture is closed, his face turned down, his torso twisted, his left arm crossing his loins to grip his right thigh. His supine body defines a space, into which he appears to stare intently, as if his suffering or fate is physically present on the ground next to him. Photographs also don’t clearly render the sword (part of a later restoration) and trumpet on the ground beside him. Or the curious circular incisions and pentagram near one of his feet, which baffle scholars today. Nor do they capture the small details of his physical perfection, the veins in his arms, the slight crease of skin around his midsection, and the delicate strength in his hands and feet. “After the statue was discovered, it quickly became a model for artists across Europe. Autocrats commissioned replicas, small bronze reproductions circulated among collectors, and artists studied it, painted it and imitated it. Thomas Jefferson wanted it, or a reproduction of it, for an art gallery he planned but never realized at Monticello. But we know more about its influence and afterlife as an ancient treasure than we know about what it depicts, who made it and how it was received by its original audience. Some scholars think it may not be a Roman reproduction at all, but a Greek original. Others, including the authors of the Oxford History of Classical Art, question whether the brief reference in Pliny refers to this work.

“The data points of the statue’s provenance are several but inconclusive: There are empty plinths for statues in Pergamum which would happily accommodate a statue of this size; there is Pliny’s reference to the Gauls and the Attalid kings who defeated them (“Several artists have represented the battles fought by Attalus and Eumenes with the Galli”), and to Nero, who brought work from Pergamum to Rome, which would explain how it made it from Asia Minor to what is now Italy. “I find it hard to dismiss Pliny,” says National Gallery curator Susan Arensberg, who organized the exhibition on the American side. Add to that the Roman’s particular interest in the Gauls — which kept them busy on the battlefield for centuries — and it’s easy to accept the standard narrative. But without a time machine, no one will ever know whether the young man was meant to appeal an ancient sense of pity, sadism or smug triumphalism.

“It’s tempting, given his beauty, to assume that pity was at least part of the mix. The particular flavor of that pity, heard as well in plays such as Aeschylus’s “The Persians,” which humanizes a defeated but dangerous enemy, is mostly foreign to contemporary audiences. The closest we might get are cryptic lines from the poet Wilfrid Owen, who died in World War I. Owen wrote that his subject was “the pity of war,” by which he seemed to mean a sense of commonality among soldiers that transcends political or military differences, as if the truth of war is how it connects rather than divides the people who fight it. “I am the enemy you killed, my friend,” wrote Owen, a sentiment ready made for projection onto this mysterious but deeply beautiful statue.”

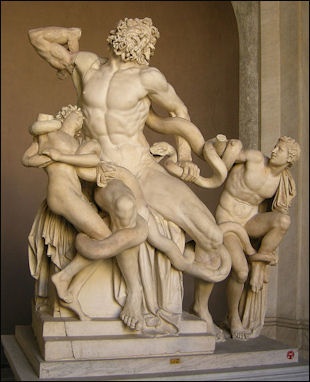

Laocoon Group

The Laocoon Group, also called Laocoön and His Sons, features a father and two sons struggling to disentangle themselves from the grasps of giant serpents. The 2000-year-old statue depicts the punishment meted out to a priest who warned the Trojans to beware of Greeks bearing gifts. Although mostly in excellent condition for an excavated sculpture, the group is missing several parts, and analysis suggests that it was remodelled in ancient times and has undergone a number of restorations since it was excavated. It is on display in the Museo Pio-Clementino, a part of the Vatican Museums.

Laocoön Group

The Laocoön Group has been one of the most famous ancient sculptures ever since it was excavated in Rome in 1506. It is very likely the same statue praised in the highest terms by the main Roman writer on art, Pliny the Elder. The figures are near life-size and the group is a little over 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in height, showing the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus being attacked by sea serpents. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The group has been called "the prototypical icon of human agony" in Western art,[4] and unlike the agony often depicted in Christian art showing the Passion of Jesus and martyrs, this suffering has no redemptive power or reward. The suffering is shown through the contorted expressions of the faces (Charles Darwin pointed out that Laocoön's bulging eyebrows are physiologically impossible), which are matched by the struggling bodies, especially that of Laocoön himself, with every part of his body straining. +

Pliny attributes the work, then in the palace of Emperor Titus, to three Greek sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodoros and Polydorus, but does not give a date or patron. In style it is considered "one of the finest examples of the Hellenistic baroque" and certainly in the Greek tradition, but it is not known whether it is an original work or a copy of an earlier sculpture, probably in bronze, or made for a Greek or Roman commission. The view that it is an original work of the 2nd century B.C. now has few if any supporters, although many still see it as a copy of such a work made in the early Imperial period, probably of a bronze original. Others see it as probably an original work of the later period, continuing to use the Pergamene style of some two centuries earlier. In either case, it was probably commissioned for the home of a wealthy Roman, possibly of the Imperial family. Various dates have been suggested for the statue, ranging from about 200 B.C. to the A.D. 70s, though "a Julio-Claudian date — between 27 BC and 68 AD — is now preferred". +

Roman Portrait Sculpture

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Roman portraiture is found on “a variety of media, most significantly sculpture and coins, but also gems, glass, and painting. This great diversity of material reflects the various uses, both public and private, for which the Romans created their portraits. Roman portraiture is also unique in comparison to that of other ancient cultures because of the quantity of surviving examples, as well as the complex and ever-evolving stylistic treatment of human features and character. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Julius Caesar

Private portrait sculpture was most closely associated with funerary contexts. Funerary altars and tomb structures were adorned with portrait reliefs of the deceased along with short inscriptions noting their family or patrons, and portrait busts accompanied cinerary urns that were deposited in the niches of large, communal tombs known as columbaria. This funerary context for portrait sculpture was rooted in the longstanding tradition of the display of wax portrait masks, called imagines, in funeral processions of the upper classes to commemorate their distinguished ancestry. These masks, portraits of noted ancestors who had held public office or been awarded special honors, were proudly housed in the household lararium, or family shrine, along with busts made of bronze, marble, or terracotta. In displaying these portraits so prominently in the public sphere, aristocratic families were able to celebrate their history of public service while honoring their deceased relatives. \^/

“In the Republic, public sculpture included honorific portrait statues of political officials or military commanders erected by the order of their peers in the Senate. These statues were typically erected to celebrate a noted military achievement, usually in connection with an official triumph, or to commemorate some worthy political achievement, such as the drafting of a treaty. A dedicatory inscription, called a cursus honorum, detailed the subject's honors and life achievements, as well as his lineage and notable ancestors. These inscriptions typically accompanied public portraits and were a uniquely Roman feature of commemoration. \^/

“The express mention of the subject's family history reflects the great influence that family history had on a Roman's political career. The Romans believed that ancestry was the best indicator of a man's ability, and so if you were the descendant of great military commanders, then you, too, had the potential to be one as well. The intense political rivalry of the late Republican period gave special meaning to the display of one's lineage and therefore necessitated its emphasis, manifested in such traditions as the cursus, wax imagines, and funerary processions, as an essential factor for success. \^/

Caligula

“With the establishment of the principate system under Augustus, the imperial family and its circle soon came to monopolize official public statuary. Official imperial portrait types were principally displayed in sebasteia, or temples of the imperial cult, and were carefully designed to project specific ideas about the emperor, his family, and his authority. These sculptures were extremely useful as propaganda tools intended to support the legitimacy of the emperor's powers. Two of the most influential, and most widely disseminated, media for imperial portraits were coins and sculpture, and official types laden with propagandistic connotation were dispersed throughout the empire to announce and identify the imperial authority. Scholars believe that official portrait types were created in the capital city of Rome itself and distributed to the provinces to serve as prototypes for local workshops, which could adapt them to conform to local iconographic traditions and therefore have more meaningful local appeal. Coins by their very nature are easily and quickly dispersed, reaching countless citizens and provincial residents, and thus the emperor's image could be seen and his power recognized by people all across the vast empire. \^/

“Conversely, in the instance of the "bad" emperors such as Nero and Domitian, whose reigns were characterized by destructive behavior and who were posthumously condemned by the Senate, imperial portraits were sometimes recycled or even destroyed. Typical effects of a damnatio memoriae, a modern term for the most severe denunciation, included the erasure of an individual's name from public inscriptions, and even assault on their portraits as if brought against the subject himself. Imperial portraits of "bad" emperors were also removed from public view and warehoused, often later recycled into portraits of private individuals or emperors of the following decades. A recarved portrait is relatively easy to recognize; certain features such as a disproportionate hairline or unusually flattened ears are typical signs that a bust had been altered from an earlier likeness.”

Roman Portrait Sculpture: The Stylistic Cycle

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The development of Roman portraiture is characterized by a stylistic cycle that alternately emphasized realistic or idealizing elements. Each stage of Roman portraiture can be described as alternately "veristic" or "classicizing," as each imperial dynasty sought to emphasize certain aspects of representation in an effort to legitimize their authority or align themselves with revered predecessors. These stylistic stages played off of one another while pushing the medium toward future artistic innovations. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Tiberius

“In the Republic, the most highly valued traits included a devotion to public service and military prowess, and so Republican citizens sought to project these ideals through their representation in portraiture. Public officials commissioned portrait busts that reflected every wrinkle and imperfection of the skin, and heroic, full-length statues often composed of generic bodies onto which realistic, called "veristic", portrait heads were attached. The overall effect of this style gave Republican ideals physical form and presented an image that the sitter wanted to express. \^/

“Beginning with Augustus, the emperors of the imperial period made full use of the medium's potential as a tool for communicating specific ideologies to the Roman populace. Augustus' official portrait type was disseminated throughout the empire and combined the heroicizing idealization of Hellenistic art with Republican ideas of individual likeness to produce a whole new scheme for portraiture that was at once innovative and yet fundamentally based in familiar aspects of traditional Roman art. Augustan and Julio-Claudian portrait types emphasized the youth, beauty, and benevolence of the new dynastic family, and in doing so, Augustus set a stylistic precedent that had lasting impact on Roman portrait sculpture up to the reign of Constantine the Great. \^/

“Classicizing idealization in portraiture allowed emperors to emphasize their loyalties to the imperial dynasty, and even legitimize their authority by visually linking themselves to their predecessors. Tiberius (r. 14–37 A.D.) was not actually related to Augustus, but his portraits portray a remarkable, and fictionalized, resemblance that connected him to the princeps and helped substantiate his position as successor. Even Tiberius' successor Caligula (r. 37–41 A.D.), who had no interest in continuing Augustus' administrative ideals and was much more concerned with promoting his own agenda, followed the Augustan and Tiberian portrait tradition of classical and idealized features that carried a strong "family" resemblance. However, during the reign of the emperor Claudius (r. 41–54 A.D.), a shift in the political atmosphere favored a return to Republican standards and so also influenced artistic styles. Portraits of Claudius reflect his increasing age and strongly resemble veristic portraits of the Republic. This trend toward realism eventually led to the characteristic styles of the second imperial dynasty: the Flavians. \^/

Marcus Aurelius

“The turbulence of the year 68/69 A.D., which saw the rise and fall of three different emperors, instigated drastic changes in Roman portraiture characterized by a return to a veristic representation that emphasized their military strengths. Portraits of Vespasian (r. 69–79 A.D.), the founder of the Flavian dynasty, similarly show him in an unidealized manner. During the Flavian era, sculptors also made remarkable advancements in technique that included a revolutionary use of the drill, and female portraiture of the period is renowned for its elaborate corkscrew hairstyles. \^/

“The cycle continued with the portraits of Trajan (r. 98–117 A.D.), who wanted to emphasize symbolic connections with Augustus and so adopted an ageless and somewhat idealized portrait type quite different from that of the Flavians. His successor Hadrian (r. 117–38 A.D.), however, went a step further and is noted as being the first emperor to adopt the Greek habit of wearing a beard. The textual interplay that was developed in the treatment of Flavian women's hairstyles was now more fully explored in male portraiture, and busts of the Hadrianic period are identified by a full head of curly hair as well as the presence of a beard. The Antonines modeled their portraits after Hadrian, and emphasized (fictional) familial resemblances to him by having themselves portrayed as never-aging, bearded adults. Continued development in Roman portrait styles was spurred by the philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–80 A.D.) and his son Commodus (r. 177–92 A.D.), whose portraits feature new levels of psychological expression that reflect changes not only in the emperors' physical state but their mental condition as well. These physical embodiments of personality and emotional expression later reach their fullest realization in the portraits of the Severan emperor Caracalla (r. 211–17 A.D.). \^/

“In contrast to the full curls typical of Hadrianic and Antonine portraits, Caracalla is shown with a short, military beard and hairstyle that were stippled across the surface of the marble for a "buzz-cut" effect, also called "negative carving." He is also shown with an intense, almost insane facial expression, which evokes his strong military background and, according to some scholars, reflects his aggressive nature. This portrait type is credited as having a profound effect on imperial portraiture in the turbulent years to follow his reign, and many of the soldier-emperors of the third century sought to legitimize their rise to power by stylistically aligning themselves with Caracalla. As time went on, these stylized aspects became increasingly prominent, and soon a pronounced attention to geometry and emotional anxiety permeated imperial portrait sculptures, as evident in the bronze statue of Trebonianus Gallus. \^/

Constantine

"This increasing dependency on geometric symmetry and abstraction contributed to the highly distinctive portraiture utilized by the Tetrarchy, a system of imperial rule based on a foundation of indivisibility and homogeneous authority shared by four co-emperors. The portraits of these Tetrarchs emphasized an abstract and stylized communal image; individualized features were forsaken in order to present them as the embodiment of a united empire. This message sought to quell the fears and anxieties born out of years of civil strife and short-lived emperors, and so in this extreme example, the portraiture of the Tetrarchy cannot be defined as the representation of individuals, but rather as the manufactured image of their revolutionary political system. \^/

“The portraiture of Constantine the Great, who defeated his rivals to become sole emperor in 326 A.D., is unique in its combination of third-century abstraction and a neo-Augustan, neo-Trajanic classical revival. Constantine favored dynastic succession and used the homogeneous precedents of his predecessors to present his sons as his apparent heirs. However, he also sought to imbue his reign with aspects of the "good" emperor Trajan, and is depicted clean-shaven and sporting the short, comma-shaped hairstyle typical of that emperor. He further disassociated himself from the Tetrarchs and soldier-emperors by having himself portrayed as youthful and serene, recalling the classicizing idealism of Augustan and Julio-Claudian portraits. In this way, Constantine's portraiture encapsulated the Roman artistic tradition of emulation and innovation, and in turn had great impact on the development of Byzantine art.”

Ancient Roman Reliefs

Coins were a kind of small bas-relief. We get a sense of what many famous Romans looked like by their portrait on coins. Roman coins have been found all over Asia and ancient Chinese coins have been found in Rome.

On a larger scale was the Column of Trajan (at Fori Imperiali), a 125-five-foot structure with a spiraling scene from Dacian Wars in the Balkans that if unwound would be 656 feet long. Built and inscribed between A.D. 106-113, the column was once topped by a statue of an Trajan, whose ashes and those of his wife are buried underneath its base. Originally it was supposed to be topped by an eagle. The statue of Trajan was destroyed in the Middle Ages.

To follow the narrative of the epic battle one has to walk around and around the column like a "circus horse" as one scholar put it. Even though the sculptures made at the top are bigger than those at the bottom, it is still hard to make them out. The figures were originally painted with bright colors and had metal weapons and the horse had metal harness.

There are a total of 150 separate scenes, the most interesting perhaps being the one that shows the Roman army crossing the Danube on a famous bridge. More attention is focused on the logistics of the battle than the actual fighting

The scenes show the interrogation of prisoners, the removal of booty, and finally the suicide of the Dacian chief while being pursued by the Roman cavalry. Dacian prisoners are treated decently after they have been captured, according to the images, while the Roman prisoners of war are tortured by Dacian women.

Collections of Roman Sculpture

The Capitoline Museum in Rome (located on Capitole Hill) is most well know for its Greek and Roman sculptures and collection of Etruscan vases, sculptures and sarcophagi. The most interesting piece in the museum is a famous Etruscan bronze of a crazy-eyed she-wolf being suckled by Renaissance depictions of Romulus and Remus who were added to the statue in the 15th century.

bacchanal relief

The Capitoline Museum some of Rome's most famous sculptures, including a marble copy of famous third-century B.C. “Dying Gaul" statue, “Satyr Resting” (the inspiration for Hawthorne's "Marble Faun") and “Venus Prudens.” In the Palazzo dei Conservatori you can see the eight-foot-high bugged eyed head and foot of Constantine the Great, his equally large foot and statues of a woman with a curly cue haircut, and a Roman patrician carrying the heads of his ancestors.

Museum delle Terme in Rome features two of the most famous sculptures in Greco-Roman art: a marble copy of the discus thrower ( an image closely associated with the Olympics) and the Dying Niobid (450-440 B.C.). The latter is an image of a woman, who according to legend, boasted about he fourteen children and humiliated the mother of Apollo and Artemis. To get even the two gods killed all of her children and then shot her in the back with an arrow. In an frantic attempt to reach back and remove the arrow her peplos fell off. She is the earliest large female nude in Greek art.

The Pio Clementine Museum in the Vatican contains one of the worlds best collection of antique sculpture, most of its from ancient Rome. The museum's most outstanding sculpture is the Lacoon which features a father and two sons struggling to disentangle themselves from the grasps of giant serpents. The 2000-year-old statue depicts the punishment meted out to a priest who warned the Trojans to beware of Greeks bearing gifts.

The Lacoon and the Vatican Museum other most famous statue — the “Apollo Belvedere” — are located outside in a protected area around a round courtyard. Described by one critic as "a symbol of all that is young and free strong and gracious," the Apollo Belvedere glorifies the male body and is most likely a copy of a Greek bronze made by Leochares around 330 B.C. The original once stood in the Agora in Athens but is now lost. The copy at the Vatican lacks its left hand and most of its arm. Scholar believe the right hand held a quiver and the left hand a bow. The elegant cloak is still in place, The first item in the Vatican collection, the Apollo Belvedere stood for four centuries in a niche in the Octagonal court until it was taken by Napoleon's army in 1798 and kept in Paris until 1816, when it was returned. For several centuries it had an fig leaf over it private parts. Other works worth checking out are the sculpture “Aphrodite of the Cnidians,” the red sarcophagus of Saint Helen (Constantine's mother), and two rooms full of sculptures of animals. One 25-meter-long hallway contains several pieces of Roman sculpture. It is worthwhile to check for hairstyles and faces to get a sense of what people looked like in ancient Rome.

Etruscan sculptureThe National Roman Museum (Palazzo Massimo, a few blocks from Termini station) has an extensive collection of mosaics, murals, sculptures and coins. Situated inside a pink 19th-century neo-Renaissance villa, it features a frescoed dining room of Livia Drusilla, the cruel wife of Emperor Augustus who was featured in Robert Graves novel “I Claudius” , and four other brilliantly colored rooms from am imperial villa known as Villa della Farnesina. Worth checking out are the Statue of Niobid, a 5th century Greek statue believed to have belonged to Julius Caesar, Roman busts, an entire room of Roman sarcophagi (some with Christian influences), mosaics that range from 2nd century B.C. to 4th century A.D., and the Nymphaeum, a first century ornamental fountain where Nero used indulge himself with his courtiers.

Roman Stuccowork

“Stucco has a long history in the Mediterranean world. Typically consisting of crushed or burned lime or gypsum mixed with sand and water, stucco was easily molded or modeled into relief decoration for walls, ceilings, and floors in both interior and exterior spaces. Stucco plaster was also used extensively in metalwork to form cores for Greek bronze sculpture and for cast impressions of bronze vessel decoration. [Source: Sarah Lepinski, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/stuc/hd_stuc.htm March 2012, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Roman stuccowork grew out of Hellenistic practices in the Mediterranean world, which, in turn, combined earlier Greek and Egyptian traditions. The ancient Greeks employed lime plaster in relief on walls to simulate monumental architecture and Egyptians used gypsum stucco for figural reliefs, freestanding sculpture, and other types of objects. \^/

“Following Greek tradition, Roman stuccowork used white lime plaster, which was lightweight and easily worked. This type of plaster was also used in contemporary fresco painting, and its preparation and application is described in detail by ancient authors such as Vitruvius and Pliny the Elder. Stuccowork grew in popularity in late Republican and early Imperial Italy as a result of the construction boom associated with brick and cement construction. While it is not as widely known today as other types of Roman decor, it played a significant role in well-planned and -executed interior spaces, complementing painted compositions, mosaic floors, and sculptural assemblages with projecting architectural elements and relief schemes. \^/

“Artists working in Roman Italy created expansive stucco schemes in private homes, tombs, and public buildings, particularly in baths. On walls, architectural members such as balustrades, column capitals, pilasters, columns, cornices, and frieze borders were fashioned in stucco and integrated into painted scheme. The stucco elements enhanced the two-dimensional decorative surfaces with projecting architectural members, adding a play of light and shadow to the interior spaces. The pieces in high relief were secured to the walls with metal rods or nails. Some forms were molded before they were attached to the walls, but other shapes and designs, such as cornices or frieze borders, were stamped into semi-dry plaster after application to the wall or ceiling. The stamped patterns imitated the egg-and-dart and vegetal borders carved on monumental architecture, a fashion that is also seen in contemporary Roman wall paintings, particularly those painted in the Second Pompeian Style. \^/

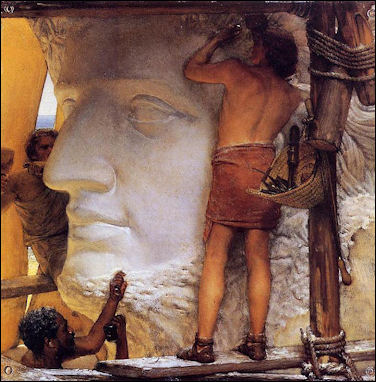

The Sculptor by

Lawrence Alma-Tadema “The general compositions of Roman stuccowork on ceilings, vaulted arches, and lunettes in Imperial Roman structures also reflect architectural forms. Influenced by the sunken framework of coffered ceilings in Hellenistic and Republican buildings, which were built in both stone and wood, Roman stuccowork formed panels framed with stamped decorative borders and cornices. Within the panels, artists modeled vegetal forms, animals, items of armor, and mythological and imaginary figures. A series of stucco reliefs in the Metropolitan Museum, which originally belonged to a large arch composition, provides a vivid example of an early Imperial stuccoed vault. The panels depict single figures that were applied by hand after the white stucco background was partially set (in general, Roman stuccowork was left white, although in some situations the backgrounds were painted). A fingerprint impression in the stucco highlights the quick practice of modeling. The artist's deft handling of the stucco is apparent in the varying relief heights of the figures as well as the added details: incisions in the semi-dry stucco outline the forms and articulate the figures, clothing, and accoutrements; holes pierced in the soft stucco indicate eyes, hair, and ribbons. \^/

“The figures represented in the Museum's panels share associations with Dionysus/Bacchus, god of wine and prosperity. A snarling panther rears slightly with a ribbon falling across its back. The dancing female figures hold drums, thyrsoi, garlands, and a fruit bowl. Floating erotes also grasp thyrsoi and garlands, and one carries a cornucopia. A striding nude male figure, possibly a satyr, with a pelt on his shoulder, holds a hare in his left hand and a staff in his right. \^/

“The popularity of Dionysiac themes in Roman art, which were rendered in various media and contexts, reflects the deity's multifaceted nature in Roman culture. Dionysus was linked to banqueting, the theater, hunting, agriculture, and the afterlife. Set within a domestic context, Dionysus and his retinue convey an attitude of a civilized life in opulent surroundings. Figural panels evoke a sense of luxury and festivity not only with their subject matter but also with their material and artistic characteristics. These facets illustrate the extent to which stuccowork corresponded thematically with other decorative media and how it augmented interior spaces with a sense of dimension and play of light. Roman stucco traditions continued throughout late antiquity, in part influencing Sasanian and later Islamic traditions, and well after antiquity, as is attested, for instance, in late medieval and Renaissance traditions.

Tanagra Figurines

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “By the last quarter of the fourth century B.C., a new repertoire of terracotta figurines entered the market. Appreciated for their naturalistic features, preserved pigments, variety, and charm, these figurines are known as Tanagras, from the site in Boeotia where great numbers of them were found. The majority of Tanagra figurines depict fashionable women or girls, elegantly wrapped in thin himations (cloaks), and sometimes wearing broad-brimmed hats and holding wreaths or fans. Previously, in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C., terracotta statuettes had been produced in Athens primarily for religious purposes, or as souvenirs of the theater. In contrast, the entirely new repertoire of Tanagra terracottas was based on an intimate examination of the personal world of mortal women and children, occasionally young men, and other characters, who are believed to have had their origins in the New Comedy of Menander. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The variety of gesture and detail that makes Tanagra figurines so appealing is due to a fairly complex method of manufacture. Like most earlier terracotta statuettes, they were formed in concave terracotta molds. The original three-dimensional figure from which the mold was taken was usually handmade of wax or terracotta, although existing figurines of terracotta, bronze, or wood occasionally were used. Clay was pressed over this prototype and, when slightly hardened, it was removed, touched up, and fired in a kiln. \^/

tanagra figure

“Until the mid-fourth century B.C., it was customary to mold only the front of the figure and to attach a simple unmodeled back; the hollow statuette was then fired. Tanagra figurines, however, were made in two-part molds—one for the front and one for the back. Often the heads and projecting arms were made in separate molds and attached to the statuette before firing. By varying the direction of the head and the position of the arms, a single type of figure could be given many slightly different poses. Wreaths, hats, or fans were handmade and separately attached. A rectangular plaque was added as a base, and vents were cut into the back of each statuette to allow moisture in the clay to escape during firing. A white slip, composed of clay and water, was applied to the entire statuette before it was fired. \^/

“After firing, the Tanagra figurines were brightly colored in a naturalistic manner with water-soluble paints. Red was used for hair, lips, shoes, and accessories, and black marked eyebrows, eyes, and other details. The flesh was painted a pale orange pink, and a reddish purple made from rose madder often was used for the drapery. Blue was used sparingly, as the pigment was expensive, and green, which was made from malachite, was never employed.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~\; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018