ANCIENT ROMAN CRAFTS

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia: In general the Roman minor arts tend to emphasize sumptuousness of materials and ornamentation. Cameos and golden jewelry were extensively produced. Among the most famous is the large Cameo of the Deified Augustus (Paris). The famous pottery from Arretium (modern Arezzo) was mass-produced and widely exported. Early examples employed a black finish and aimed at imitation of metallic effects. From the time of Augustus, the ware was characterized by a deep red glaze with decorative figures in low relief applied to the body of the vase. During the A.D. 1st century new processes were invented for making glass, and techniques were developed for the imitation of precious stones that made possible the production of fine murrhine vases (e.g., the famous Portland vase, British Museum). [Source: The Columbia Encyclopedia]

National Geographic reports: The Romans are famed for their grandiose marble sculptures, requiring exquisite talent and expertise. One of the most famous is Trajan’s Column in Rome, commissioned by Emperor Trajan after he conquered Dacia (modern-day Romania) during his campaigns from A.D. 101 to 106, and adorned with a spiral frieze that commemorates the Dacia battles. But Roman craftsmen and artisans also created refined everyday pieces that showcase their mastery, including jewelry and musical instruments. [Source National Geographic, November 8, 2022]

Most Roman artisans resided in Rome’s working-class neighborhoods along the Tiber’s southern bank. The Travestere neighborhood today retains the essence of an artisan neighborhood, where glass blowers, shoemakers, and marble workers once plied their trade. The Romans were especially gifted at gold, silver, and other metal work, largely thanks to the influence of their Greek and Etruscan predecessors. Masters passed their skills from father to son, master to apprentice, over centuries.

Precious metals, glass, turquoise, pearls, garnets, and other gemstones were used in finely-crafted Roman jewelry. Among the interesting objects that have been found are a bone-carved hairpin that depicts a female figurine with a beehive hairstyle; two copper brooches that emulate dragons in blue and red enamel; and a conch shell trumpet from first-century Pompeii. An intricate, snake-shaped ring of gold dating to the first century B.C. was found in Egypt.

Noteworthy objects found at an ancient Roman pottery workshop in Egypt include a mold-blown glass vessel with an image of racing horse-drawn chariots; a blue bronze serving bowl in the shape of a seashell; a pink clay bowl decorated with floral and beaded reliefs; and a thin-necked 10-centimeter-high bottle made of mold-blown glass with floral scrolls and floating handles. [Source National Geographic]

RELATED ARTICLES:

JEWELRY IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN GLASS europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN MOSAICS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN SCULPTURE: HISTORY, TYPES, MATERIALS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMOUS PIECES OF ANCIENT ROMAN SCULPTURE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ART europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN PAINTING: HISTORY, FRESCOES, TOMBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN-ERA MUMMIES: RITUALS, GOLD AND PORTRAITS OF THE DEAD europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Crafts”, Illustrated, by Donald Strong, David Brown Amazon.com;

“Roman Art in the Private Sphere: New Perspectives on the Architecture and Decor of the Domus, Villa, and Insula” by Elaine K. Gazda (1991) Amazon.com;

“Roman Artisans and the Urban Economy” by Cameron Hawkins (2021) Amazon.com;

“Roman Pottery in the Archaeological Record” by J. Theodore Peña Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Mediterranean Roman Pottery” by John W. Hayes (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Citizens, Soldiers, and Freedmen in the Roman World” by E. D'Ambra, Guy P. R. Metraux (2006) Amazon.com;

“Materiality in Roman Art and Architecture: Aesthetics, Semantics and Function” by Annette Haug, Adrian Hielscher, M. Taylor Lauritsen Amazon.com;

“A Cultural History of Objects in Antiquity” by Robin Osborne (2024) Amazon.com;

“Carving as Craft: Palatine East and the Greco-Roman Bone and Ivory Carving Tradition”

by Archer St. Clair Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Jewellery” by Filippo Coarelli (1970) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Glass in the J. Paul Getty Museum” by Anastassios Antonaras (2025) Amazon.com;

“Small Stuff of Roman Antiquity” by Emily Gowers (2025) Amazon.com;

“Luxus: The Sumptuous Arts of Greece and Rome” by Kenneth Lapatin (2015) Amazon.com;

“Style and Function in Roman Decoration: Living with Objects and Interiors”

by Ellen Swift (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Small Finds and Vessel Glass from Insula VI.1 Pompeii: Excavations 1995-2006" by H.E.M. Cool Amazon.com;

“Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Alison E. Cooley (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pompeii”, Illustrated, by Joanne Berry (2007) Amazon.com;

“Roman Furniture” by A.T. Croom (2007) Amazon.com;

“Studies in Ancient Furniture - Couches and Beds of the Greeks, Etruscans and Romans” by Caroline L Ransom (2010) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Furniture and Other Works of Art Hardcover – September 20, 2004

by Vincent J Robinson(1902) Amazon.com;

“Roman Woodworking” by Roger B. Ulrich (2013) Amazon.com;

“Roman Art” by Michael Siebler and Norbert Wolf (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art of the Roman Empire: 100-450 AD (Oxford History of Art) by Jaś Elsner Amazon.com;

“A History of Roman Art” by Steven L. Tuck Amazon.com;

“Art & Archaeology of the Roman World” by Mark Fullerton (2020) Amazon.com

“The Language of Images in Roman Art” by Tonio Hölscher (2004) Amazon.com;

“Power of Images in the Age of Augustus” by Paul Zanker and Alan Shapiro (1988) Amazon.com

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

Jewelry in Ancient Rome

The upper classes spent large sums of money were expended on precious stones and on shoes and other garments embroidered with pearls. Heavy gold jewelry was fashionable among Roman aristocrats in the A.D. first century. Around the same time women wore gold earring with pearls and necklaces made from small gold beads, diadems of gold laurels and parures with emeralds set in gold. Rings were made with small bits of stone, glass or amethyst with tin pictures scratched on their surfaces.

Almost all the precious stones that are known to us were familiar to the Romans and were to be found in the jewel-casket of the wealthy lady. The pearl, however, seems to have been in all times the favorite. No adequate description of these articles can be given here; no illustrations can do them justice. It will have to suffice that Suetonius says that Caesar paid six million sesterces (nearly $300,000) for a single pearl, which he gave to Servilia, the mother of Marcus Brutus, and that Lollia Paulina, the wife of the Emperor Caligula, possessed a single set of pearls and emeralds which is said by Pliny the Elder to have been valued at forty million sesterces (nearly $2,000,000). [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Armbands seem to have been in fashion around the time Pompeii was destroyed. Gold ones shaped like snakes with a head at each of their body were excavated there. At Pompeii earrings have been found set with pearls, gold balls and uncut emeralds clustered like grapes, “I see they do not stop at attracting a single large pearl to each ear," the Roman philosopher Seneca observed during the A.D. 1st century. “Female folly had not crushed men enough unless two or three patrimonies hung from their ears."

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Ancient Roman Pottery

ceramic lamp Roman pottery included red earthenware known as Samian ware and black pottery known as Etruscan ware, which was different than the pottery actually made by the Etruscans. The Roman pioneered the use of ceramics for things like bathtubs and drainage pipes.

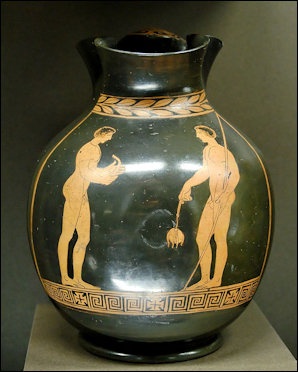

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “For nearly 300 years, Greek cities along the coasts of southern Italy and Sicily regularly imported their fine ware from Corinth and, later, Athens. By the third quarter of the fifth century B.C., however, they were acquiring red-figured pottery of local manufacture. As many of the craftsmen were trained immigrants from Athens, these early South Italian vases were closely modeled after Attic prototypes in both shape and design. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“By the end of the fifth century B.C., Attic imports ceased as Athens struggled in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War in 404 B.C. The regional schools of South Italian vase painting—Apulian, Lucanian, Campanian, Paestan—flourished between 440 and 300 B.C. In general, the fired clay shows much greater variation in color and texture than that which is found in Attic pottery. A distinct preference for added color, especially white, yellow, and red, is characteristic of South Italian vases in the fourth century B.C. Compositions, especially those on Apulian vases, tend to be grandiose, with statuesque figures shown in several tiers. There is also a fondness for depicting architecture, with the perspective not always successfully rendered. \^/

“Almost from the beginning, South Italian vase painters tended to favor elaborate scenes from daily life, mythology, and Greek theater. Many of the paintings bring to life stage practices and costumes. A particular fondness for the plays of Euripides testifies to the continued popularity of Attic tragedy in the fourth century B.C. in Magna Graecia. In general, the images often show one or two highlights of a play, several of its characters, and often a selection of divinities, some of which may or may not be directly relevant. Some of the liveliest products of South Italian vase painting in the fourth century B.C. are the so-called phlyax vases, which depict comics performing a scene from a phlyax, a type of farce play that developed in southern Italy. These painted scenes bring to life the boisterous characters with grotesque masks and padded costumes.”

Funerary Vases in Southern Italy and Sicily

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Most extant South Italian vases have been discovered in funerary contexts, and a significant number of these vases were likely produced solely as grave goods. This function is demonstrated by the vases of various shapes and sizes that are open at the bottom, rendering them useless for the living. Often the vases with open bottoms are monumentalized shapes, particularly volute-kraters, amphorae, and loutrophoroi, which began to be produced in the second quarter of the fourth century B.C. The perforation at the bottom prevented damage during firing and also allowed them to serve as grave markers. Liquid libations offered to the dead were poured through the containers into the soil containing the deceased's remains. Evidence for this practice exists in the cemeteries of Tarentum (modern Taranto), the only significant Greek colony in the region of Apulia (modern Puglia).

amphorae, common and used for storing food, wine and other things

“Most surviving examples of these monumental vases are not found in Greek settlements, but in chamber tombs of their Italic neighbors in northern Apulia. In fact, the high demand for large-scale vases among the native peoples of the region seems to have spurred Tarentine émigrés to establish vase painting workshops by the mid-fourth century B.C. at Italic sites such as Ruvo, Canosa, and Ceglie del Campo. \^/

“The imagery painted on these vases, rather than their physical structure, best reflects their intended sepulchral function. The most common scenes of daily life on South Italian vases are depictions of funerary monuments, usually flanked by women and nude youths bearing a variety of offerings to the grave site such as fillets, boxes, perfume vessels (alabastra), libation bowls (phialai), fans, bunches of grapes, and rosette chains. When the funerary monument includes a representation of the deceased, there is not necessarily a strict correlation between the types of offerings and the gender of the commemorated individual(s). For instance, mirrors, traditionally considered a female grave good in excavation contexts, are brought to monuments depicting individuals of both genders. \^/

“The preferred type of funerary monument painted on vases varies from region to region within southern Italy. On rare occasions, the funerary monument may consist of a statue, presumably of the deceased, standing on a simple base. Within Campania, the grave monument of choice on vases is a simple stone slab (stele) on a stepped base. In Apulia, vases are decorated with memorials in the form of a small templelike shrine called a naiskos. The naiskoi usually contain within them one or more figures, understood as sculptural depictions of the deceased and their companions. The figures and their architectural setting are usually painted in added white, presumably to identify the material as stone. Added white to represent a statue may also be seen on an Apulian column-krater where an artist applied colored pigment to a marble statue of Herakles. Furthermore, painting figures within naiskoi in added white differentiates them from the living figures around the monument who are rendered in red-figure. There are exceptions to this practice—red-figure figures within naiskoi may represent terracotta statuary. As South Italy lacks indigenous marble sources, the Greek colonists became highly skilled coroplasts, able to render even lifesized figures in clay. \^/

“By the mid-fourth century B.C., monumental Apulian vases typically presented a naiskos on one side of the vase and a stele, similar to those on Campanian vases, on the other. It was also popular to pair a naiskos scene with a complex, multifigured mythological scene, many of which were inspired by tragic and epic subjects. Around 330 B.C., a strong Apulianizing influence became evident in Campanian and Paestan vase painting, and naiskos scenes began appearing on Campanian vases. The spread of Apulian iconography may be connected to the military activity of Alexander the Molossian, uncle of Alexander the Great and king of Epirus, who was summoned by the city of Tarentum to lead the Italiote League in efforts to reconquer former Greek colonies in Lucania and Campania. \^/

“In many naiskoi, vase painters attempted to render the architectural elements in three-dimensional perspective, and archaeological evidence suggests that such monuments existed in the cemeteries of Tarentum, the last of which stood until the late nineteenth century. The surviving evidence is fragmentary, as modern Taranto covers much of the ancient burial grounds, but architectural elements and sculptures of local limestone are known. The dating of these objects is controversial; some scholars place them as early as 330 B.C., while others date them all during the second century B.C. Both hypotheses postdate most, if not all, of their counterparts on vases. On a fragmentary piece in the Museum's collection, which decorated either the base or back wall of a funerary monument, a pilos helmet, sword, cloak, and cuirass are suspended on the background. Similar objects hang within the painted naiskoi. Vases that show naiskoi with architectural sculpture, such as patterned bases and figured metopes, have parallels in the remains of limestone monuments. \^/

southern Italian vase painting of athletes

“Above the funerary monuments on monumental vases there is frequently an isolated head, painted on the neck or shoulder. The heads may rise from a bell-flower or acanthus leaves and are set within a lush surround of flowering vines or palmettes. Heads within foliage appear with the earliest funerary scenes on South Italian vases, beginning in the second quarter of the fourth century B.C. Typically the heads are female, but heads of youths and satyrs, as well as those with attributes such as wings, a Phrygian cap, a polos crown, or a nimbus, also appear. Identification of these heads has proven difficult, as there is only one known example, now in the British Museum, whose name is inscribed (called "Aura"—"Breeze"). No surviving literary works from ancient southern Italy illuminate their identity or their function on the vases. The female heads are drawn in the same manner as their full-length counterparts, both mortal and divine, and are usually shown wearing a patterned headdress, a radiate crown, earrings, and a necklace. Even when the heads are bestowed with attributes, their identity is indeterminate, allowing a variety of possible interpretations. More narrowly defining attributes are very rare and do little to identify the attribute-less majority. The isolated head became very popular as primary decoration on vases, particularly those of small scale, and by 340 B.C., it was the single most common motif in South Italian vase painting. The relation of these heads, set in rich vegetation, to the grave monuments below them suggests they are strongly connected to fourth-century B.C. concepts of a hereafter in southern Italy and Sicily. \^/

“Although the production of South Italian red-figure vases ceased around 300 B.C., making vases purely for funerary use continued, most notably at Centuripe, a town in eastern Sicily near Mount Etna. The numerous polychrome terracotta figurines and vases of the third century B.C. were decorated with tempera colors after firing. They were further elaborated with complex vegetal and architecturally inspired relief elements. One of the most common shapes, a footed dish called a lekanis, was often constructed of independent sections (foot, bowl, lid, lid knob, and finial), resulting in few complete pieces today. On some pieces, such as the lebes in the Museum's collection, the lid was made in one piece with the body of the vase, so that it could not function as a container. The construction and fugitive decoration of Centuripe vases indicate their intended function as grave goods. The painted imagery relates to weddings or the Dionysiac cult, whose mysteries enjoyed great popularity in southern Italy and Sicily, presumably due to the blissful afterlife promised to its initiates.

Five Wares of South Italian Vase Painting

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “South Italian vases are ceramics, mostly decorated in the red-figure technique, that were produced by Greek colonists in southern Italy and Sicily, the region often referred to as Magna Graecia or "Great Greece." Indigenous production of vases in imitation of red-figure wares of the Greek mainland occurred sporadically in the early fifth century B.C. within the region. However, around 440 B.C., a workshop of potters and painters appeared at Metapontum in Lucania and soon after at Tarentum (modern-day Taranto) in Apulia. It is unknown how the technical knowledge for producing these vases traveled to southern Italy. Theories range from Athenian participation in the founding of the colony of Thurii in 443 B.C. to the emigration of Athenian artisans, perhaps encouraged by the onset of the Peloponnesian War in 431 B.C. The war, which lasted until 404 B.C., and the resulting decline of Athenian vase exports to the west were certainly important factors in the successful continuation of red-figure vase production in Magna Graecia. The manufacture of South Italian vases reached its zenith between 350 and 320 B.C., then gradually tapered off in quality and quantity until just after the close of the fourth century B.C. [Source: Keely Heuer, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, December 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

Lucanian vase

“Modern scholars have divided South Italian vases into five wares named after the regions in which they were produced: Lucanian, Apulian, Campanian, Paestan, and Sicilian. South Italian wares, unlike Attic, were not widely exported and seem to have been intended solely for local consumption. Each fabric has its own distinct features, including preferences in shape and decoration that make them identifiable, even when exact provenance is unknown. Lucanian and Apulian are the oldest wares, established within a generation of each other. Sicilian red-figure vases appeared not long after, just before 400 B.C. By 370 B.C., potters and vase painters migrated from Sicily to both Campania and Paestum, where they founded their respective workshops. It is thought that they left Sicily due to political upheaval. After stability returned to the island around 340 B.C., both Campanian and Paestan vase painters moved to Sicily to revive its pottery industry. Unlike in Athens, almost none of the potters and vase painters in Magna Graecia signed their work, thus the majority of names are modern designations. \^/

“Lucania, corresponding to the "toe" and "instep" of the Italian peninsula, was home to the earliest of the South Italian wares, characterized by the deep red-orange color of its clay. Its most distinctive shape is the nestoris, a deep vessel adopted from a native Messapian shape with upswung side handles sometimes decorated with disks. Initially, Lucanian vase painting very closely resembled contemporary Attic vase painting, as seen on a finely drawn fragmentary skyphos attributed to the Palermo Painter. Favored iconography included pursuit scenes (mortal and divine), scenes of daily life, and images of Dionysos and his adherents. The original workshop at Metaponto, founded by the Pisticci Painter and his two chief colleagues, the Cyclops and Amykos Painters, disappeared between 380 and 370 B.C.; its leading artists moved into the Lucanian hinterland to sites such as Roccanova, Anzi, and Armento. After this point, Lucanian vase painting became increasingly provincial, reusing themes from earlier artists and motifs borrowed from Apulia. With the move to more remote parts of Lucania, the color of the clay also changed, best exemplified in the work of the Roccanova Painter, who applied a deep pink wash to heighten the light color. After the career of the Primato Painter, the last of the notable Lucanian vase painters, active between ca. 360 and 330 B.C., the ware consisted of poor imitations of his hand until the last decades of the fourth century B.C., when production ceased. \^/

“More than half of extant South Italian vases come from Apulia (modern Puglia), the "heel" of Italy. These vases were originally produced in Tarentum, the major Greek colony in the region. The demand became so great among the native peoples of the region that by the mid-fourth century B.C., satellite workshops were established in Italic communities to the north such as Ruvo, Ceglie del Campo, and Canosa. A distinctive shape of Apulia is the knob-handled patera, a low-footed, shallow dish with two handles rising from the rim. The handles and rim are elaborated with mushroom-shaped knobs. Apulia is also distinguished by its production of monumental shapes, including the volute-krater, the amphora, and the loutrophoros. These vases were primarily funerary in function. They are decorated with scenes of mourners at tombs and elaborate, multifigured mythological tableaux, a number of which are rarely, if ever, seen on the vases of the Greek mainland and are otherwise only known through literary evidence. Mythological scenes on Apulian vases are depictions of epic and tragic subjects and were likely inspired by dramatic performances. Sometimes these vases provide illustrations of tragedies whose surviving texts, other than the title, are either highly fragmentary or entirely lost. These large-scale pieces are categorized as "Ornate" in style and feature elaborate floral ornament and much added color, such as white, yellow, and red. Smaller shapes in Apulia are typically decorated in the "Plain" style, with simple compositions of one to five figures. Popular subjects include Dionysos, as both god of theater and wine, scenes of youths and women, frequently in the company of Eros, and isolated heads, usually that of a woman. Prominent, particularly on column-kraters, is the depiction of the indigenous peoples of the region, such as the Messapians and Oscans, wearing their native dress and armor. Such scenes are usually interpreted as an arrival or departure, with the offering of a libation. Counterparts in bronze of the wide belts worn by the youths on a column-krater attributed to the Rueff Painter have been found in Italic tombs. The greatest output of Apulian vases occurred between 340 and 310 B.C., despite political upheaval in the region at the time, and most of the surviving pieces can be assigned to its two leading workshops—one led by the Darius and Underworld Painters and the other by the Patera, Ganymede, and Baltimore Painters. After this floruit, Apulian vase painting declined rapidly. \^/

Lucian crater with a symposium scene attributed to Python

“Campanian vases were produced by Greeks in the cities of Capua and Cumae, which were both under native control. Capua was an Etruscan foundation that passed into the hands of Samnites in 426 B.C. Cumae, one of the earliest of the Greek colonies in Magna Graecia, was founded on the Bay of Naples by Euboeans no later than 730–720 B.C. It, too, was captured by native Campanians in 421 B.C., but Greek laws and customs were retained. The workshops of Cumae were founded slightly later than those of Capua, around the middle of the fourth century B.C. Notably absent in Campania are monumental vases, perhaps one of the reasons why there are fewer mythological and dramatic scenes. The most distinctive shape in the Campanian repertoire is the bail-amphora, a storage jar with a single handle that arches over the mouth, often pierced at its top. The color of the fired clay is a pale buff or light orange-yellow, and a pink or red wash was often painted over the entire vase before it was decorated to enhance the color. Added white was used extensively, particularly for the exposed flesh of women. While vases of the Sicilian emigrants who settled in Campania are found at a number of sites in the region, it is the Cassandra Painter, the head of a workshop in Capua between 380 and 360 B.C., who is credited as being the earliest Campanian vase painter. Close to him in style is the Spotted Rock Painter, named for an unusual feature of Campanian vases that incorporates the area's natural topography, shaped by volcanic activity. Depicting figures seated upon, leaning against, or resting a raised foot on rocks and rock piles was a common practice in South Italian vase painting. But on Campanian vases, these rocks are often spotted, representing a form of igneous breccia or agglomerate, or they take the sinuous forms of cooled lava flows, both of which were familiar geological features of the landscape. The range of subjects is relatively limited, the most characteristic being representations of women and warriors in native Osco-Samnite dress. The armor consists of a three-disk breastplate and helmet with a tall vertical feather on both sides of the head. Local dress for women consists of a short cape over the garment and a headdress of draped fabric, rather medieval in appearance. The figures participate in libations for departing or returning warriors as well as in funerary rites. These representations are comparable to those found in painted tombs of the region as well as at Paestum. Also popular in Campania are fish plates, with great detail paid to the different species of sea life painted on them. Around 330 B.C., Campanian vase painting became subject to a strong Apulianizing influence, probably due to the migration of painters from Apulia to both Campania and Paestum. In Capua, production of painted vases concluded around 320 B.C., but continued in Cumae until the end of the century. \^/

“The city of Paestum is located in the northwest corner of Lucania, but stylistically its pottery is closely connected to that of neighboring Campania. Like Cumae, it was a former Greek colony, conquered by the Lucanians around 400 B.C. While Paestan vase painting does not feature any unique shapes, it is set apart from the other wares for being the only one to preserve the signatures of vase painters: Asteas and his close colleague Python. Both were early, accomplished, and highly influential vase painters who established the ware's stylistic canons, which changed only slightly over time. Typical features include dot-stripe borders along the edges of drapery and the so-called framing palmettes typical on large- or medium-scaled vases. The bell-krater is a particularly favored shape. Scenes of Dionysos predominate; mythological compositions occur, but tend to be overcrowded, with additional busts of figures in the corners. The most successful images on Paestan vases are those of comedic performances, often termed "phlyax vases" after a type of farce developed in southern Italy. However, evidence indicates an Athenian origin for at least some of these plays, which feature stock characters in grotesque masks and exaggerated costumes. Such phlyax scenes are also painted on Apulian vases. \^/

“Sicilian vases tend to be small in scale and popular shapes include the bottle and the skyphoid pyxis. The range of subjects painted on vases is the most limited of all the South Italian wares, with most vases showing the feminine world: bridal preparations, toilet scenes, women in the company of Nike and Eros or simply by themselves, often seated and gazing expectantly upward. After 340 B.C., vase production seems to have been concentrated in the area of Syracuse, at Gela, and around Centuripe near Mount Etna. Vases were also produced on the island of Lipari, just off the Sicilian coast. Sicilian vases are striking for their ever increasing use of added colors, particularly those found on Lipari and near Centuripe, where in the third century B.C. there was a thriving manufacture of polychrome ceramics and figurines.

Praenestine Cistae

Praenestine Cistae depicting Helen of Troy and Paris

Maddalena Paggi of the The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Praenestine cistae are sumptuous metal boxes mostly of cylindrical shape. They have a lid, figurative handles, and feet separately manufactured and attached. Cistae are covered with incised decoration on both body and lid. Little studs are placed at equal distance at a third of the cista's height all around, regardless of the incised decoration. Small metal chains were attached to these studs and probably used to lift the cistae. [Source: Maddalena Paggi, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“As funerary objects, cistae were placed in the tombs of the fourth-century necropolis at Praeneste. This town, located 37 kilometers southeast of Rome in the region of Latius Vetus, was an Etruscan outpost in the seventh century B.C., as the wealth of its princely burials indicates. Excavations conducted at Praeneste in the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century were primarily aimed at the recovery of these precious-metal objects. The subsequent demand for cistae and mirrors caused the systematic plundering of the Praenestine necropolis. Cistae acquired value and importance in the antiquities market, which also encouraged the production of forgeries. \^/

“Cistae are a very heterogeneous group of objects, but vary in terms of quality, narrative, and size. Artistically, cistae are complex objects in which different techniques and styles coexist: engraved decoration and cast attachments seem to be the result of different technical expertise and traditions. Collaboration of craftsmanship was required for their two-stage manufacturing process: the decoration (casting and engraving) and the assembly. \^/

“The most famous cista and the first to be discovered is the Ficoroni presently in the Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome, named after the well-known collector Francesco de' Ficoroni (1664–1747), who first owned it. Although the cista was found at Praeneste, its dedicatory inscription indicates Rome as the place of production: NOVIOS PLVTIUS MED ROMAI FECID/ DINDIA MACOLNIA FILEAI DEDIT (Novios Plutios made me in Rome/ Dindia Macolnia gave me to her daughter). These objects have often been taken as examples of middle Republican Roman art. However, the Ficoroni inscription remains the only evidence for this theory, while there is ample evidence for a local production at Praeneste. \^/

“The high-quality Praenestine cistae often adhere to the classical ideal. The proportions, composition, and style of the figures indeed present close connections and knowledge of Greek motifs and conventions. The engraving of the Ficoroni cista portrays the myth of the Argonauts, the conflict between Pollux and Amicus, in which Pollux is victorious. The engravings on the Ficoroni cista have been viewed as a reproduction of a lost fifth-century painting by Mikon. Difficulties remain, however, in finding precise correspondences between Pausanias' description of such a painting and the cista. \^/

“The function and use of Praenestine cistae are still unresolved questions. We can safely say that they were used as funerary objects to accompany the deceased into the next world. It has also been suggested that they were used as containers for toiletries, like a beauty case. Indeed, some recovered examples contained small objects such as tweezers, make-up boxes, and sponges. The large size of the Ficoroni cista, however, excludes such a function and points toward a more ritualistic use. \^/

Roman Glass Making

The Romans made drinking cups, vases, bowls, storage jars, decorative items and other object in a variety of shapes and colors. using blown glass. The Roman, wrote Seneca, read "all the books in Rome" by peering at them through a glass globe. The Romans made sheet glass but never perfected the process partly because windows weren't considered necessary in the relatively warm Mediterranean climate.

The Romans made a number of advancements, the most notable of which was mold-blown glass, a technique still used today. Developed in the eastern Mediterranean in the 1st century B.C., this new technique allowed glass to be made transparent and in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. It also allowed glass to be mass produced, making glass something that ordinary people could afford as well as the rich. The use of mold-blown glass spread throughout the Roman empire and was influenced by different cultures and arts.

Roman glass amphora With the core-form mold-blown technique, globs of glass are heated in a furnace until they become glowing orange orbs. Glass threads are wound around a core with a handling piece of metal. Craftsmen then roll, blow and spin the glass to get the shapes they want.

With the casting technique, a mold is formed with a model. The mold is filled with crushed or powdered glass and heated. After cooling down, the plank is removed from the mold, and the interior cavity is drilled and exterior is well cut. With the mosaic glass technique, rods of glass are fused, drawn and cut into canes. These canes are arranged in a mold and heated to make a vessel.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “At the height of its popularity and usefulness in Rome, glass was present in nearly every aspect of daily life—from a lady's morning toilette to a merchant's afternoon business dealings to the evening cena, or dinner. Glass alabastra, unguentaria, and other small bottles and boxes held the various oils, perfumes, and cosmetics used by nearly every member of Roman society. Pyxides often contained jewelry with glass elements such as beads, cameos, and intaglios, made to imitate semi-precious stone like carnelian, emerald, rock crystal, sapphire, garnet, sardonyx, and amethyst. Merchants and traders routinely packed, shipped, and sold all manner of foodstuffs and other goods across the Mediterranean in glass bottles and jars of all shapes and sizes, supplying Rome with a great variety of exotic materials from far-off parts of the empire. [Source: Rosemarie Trentinella, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Other applications of glass included multicolored tesserae used in elaborate floor and wall mosaics, and mirrors containing colorless glass with wax, plaster, or metal backing that provided a reflective surface. Glass windowpanes were first made in the early imperial period, and used most prominently in the public baths to prevent drafts. Because window glass in Rome was intended to provide insulation and security, rather than illumination or as a way of viewing the world outside, little, if any, attention was paid to making it perfectly transparent or of even thickness. Window glass could be either cast or blown. Cast panes were poured and rolled over flat, usually wooden molds laden with a layer of sand, and then ground or polished on one side. Blown panes were created by cutting and flattening a long cylinder of blown glass.”

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ROMAN GLASS europe.factsanddetails.com

Secret Cabinet and the National Archaeological Museum in Naples

The National Archaeological Museum in Naples is one of the largest and best archeological museums in the world. Located with a 16th century palazzo, it houses a wonderful collection of statues, wall paintings, mosaics and everyday utensils, many of them unearthed in Pompeii and Herculaneum. In fact, most of the outstanding and well-preserved pieces from Pompeii and Herculaneum are in the archeological museum.

Among the treasures are majestic equestrian statues of proconsul Marcus Nonius Balbus, who helped restore Pompeii after the A.D. 62 earthquake; the Farnese Bull, the largest known ancient sculpture; the statue of Doryphorus, the spear bearer, a Roman copy of one of classical Greece's most famous statues; and huge voluptuous statues of Venus, Apollo and Hercules that bear witness to Greco-Roman idealizations of strength, pleasure, beauty and hormones.

The most famous work in the museum is the spectacular and colorful mosaic known both as the Battle of Issus and Alexander and the Persians . Showing Alexander the Great battling King Darius and the Persians," the mosaic was made from 1.5 million different pieces, almost all of them cut individually for a specific place on the picture. Other Roman mosaics range from simple geometric designs to breathtaking complex pictures.

Also worth look are the most outstanding artifacts found at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum are located here. The most unusual of these are the dark bronze statues of water carriers with spooky white eyes made of glass paste. A wall painting of peaches and a glass jar from Herculaneum could easily be mistaken for a Cezanne painting. In another colorful wall painting from Herculaneum a dour Telephus is being seduced by a naked Hercules while a lion, a cupid, a vulture and an angel look on.

Other treasures include the statue of an obscene male fertility god eying a bathing maiden four times his size; a beautiful portrait of a couple holding a papyrus scroll and a waxed tablet to show their importance; and wall paintings of Greek myths and theater scenes with comic and tragic masked actors. Make sure to check out the Farnese Cup in the Jewels collection. The Egyptian collection is often closed.

The Secret Cabinet (in National Archaeological Museum) is a couple of rooms with erotic sculptures, artifacts and frescoes from ancient Rome and Etruria that were locked away for 200 years. Unveiled in the year 2000, the two rooms contain 250 frescoes, amulets, mosaics, statues, oil laps," votive offerings, fertility symbols and talismans. The objects include a second-century marble statute of the mythological figure Pan copulating with a goat found at the Valli die Papyri in 1752. Many of the objects were found in bordellos in Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The collection began with as a royal museum for obscene antiques started by the Bourbon King Ferdinand in 1785. In 1819, the objects were moved to a new museum where they were displayed until 1827, when it was closed after complaints by a priest that descried the room as hell and a "corrupter of the morals or modest youth." The room was opened briefly after Garibaldi set up a dictatorship in southern Italy in 1860.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024