OVID

Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso, better known as Ovid, is regarded as the premier Roman love poet. Brought up in the province to an equestrian family, he moved to Rome as a teenager and wrote about the sensuous life he enjoyed in upper class Roman society. Famed as a kind of Roman Casanova, he married three times, had a great many lovers and was involved in a highly-publicized sex scandal.

Ovid once wrote, "Offered a sexless heaven, I'd say no thank you, women are such sweet hell." He wrote that he learned about love from the mysterious Corinna who he rhapsodized about in his early “ Loves” . As a teenager he wrote they were "two adolescents, exploring a booby-trapped world of adult passions and temptations, and playing private games, first with their society, then — “liaisons dangeruses” “with one another."

Ovid was also a great storyteller. His “Metamorphosis” told the story of the Greek gods in a Roman context. He also poked fun of them. His irreverence helped led to the tossing of the Greek gods and replacing them with Roman ones. Ovid originated many versions of the myth stories we know today such as the King Midas, golden touch tale.

Esteban Berché wrote in National Geographic History: Recognized today for the Metamorphoses, his dazzling reworking of Greek and Latin myths, Ovid was known during his time for vibrant, controversial love poetry, including the Amores (The Loves) and the Ars amatoria (The Art of Love). These frank poetic reflections on Roman sexual customs brought him fame but also played a role in his downfall.[Source Esteban Berché, National Geographic History, November 26, 2019]

After publishing his magnum opus, Ovid fell out of imperial favor, was forced to leave Rome, and exiled to Tomis, a city on the Black Sea. It was here, on the fringes of the empire, that Ovid pined for his beloved Rome and begged to return. By Ovid’s own account, the exile was punishment for an “error” that enraged the emperor Augustus. Ovid considered himself lucky that he escaped execution for the offense but never recorded any specific details about what he did wrong. Scholars have puzzled over the cause of the exile for centuries, which remains unsolved to this day.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEX POETRY FROM ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

LUCRETIUS: THE GREAT POET AND ARTICULATOR OF EPICURIANISM europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN LITERATURE, BOOKS AND THE BOOK MARKET europe.factsanddetails.com

CLASSICS OF ROMAN LITERATURE europe.factsanddetails.com

SATYRICON europe.factsanddetails.com

AENEID: VIRGIL, STORY, HISTORY, THEMES europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN SATIRES europe.factsanddetails.com

JUVENAL'S SATIRES europe.factsanddetails.com

DRAMA IN ANCIENT ROME: HISTORY, COMEDY, PLAYWRIGHTS AND PLAYS europe.factsanddetails.com

THEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE: HISTORY, TYPES, PARTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Roman Poetry Selections (Catullus [c.84-c.54 B.C.], Horace [5-8 B.C.], Martial [40-103/4 CE]) Then Again, Internet Archive web.archive.org; Sulpicia (Late 1st Cent. A.D.): Poems Diotima, Internet Archive web.archive.org; The only surviving Roman female poet. Theoi Classical Texts Library, translations of works of ancient Greek and Roman literature, with an impressive gallery of illustrations Internet Archive web.archive.org ; Tools of the Trade for the Study of Roman Literature, by Lowell Edmunds and Shirley Werner, Internet Archive web.archive.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Poetry: From the Republic to the Silver Age” by Professor Dorothea Wender (1980) Amazon.com;

“Roman Poets of the Early Empire (Penguin Classics) by A. J. Boyle and J. P. Sullivan (1992) Amazon.com;

"The Complete Odes and Epodes” (Oxford World's Classics) by Horace, translated by David West Amazon.com;

"The Erotic Poems (Penguin Classics) by Ovid and Peter Green (1983) Amazon.com;

“The Art Of Love” by Ovid, translated by Henry T. Riley (2018) Amazon.com;

“Metamorphoses” by Ovid, 8 AD (Oxford World's Classics) Amazon.com;

“Tales from Ovid” by Ted Hughes (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Sleep of Reason: Erotic Experience and Sexual Ethics in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Martha C. Nussbaum , Juha Sihvola (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Poems of Catullus” (Oxford World's Classics) by Catullus, translated by Guy Lee Amazon.com;

“Switch: The Complete Catullus (Carcanet Classics) by Isobel Williams (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Poems of Catullus: A Bilingual Edition”

by Gaius Valerius Valerius Catullus and Peter Green (2007) Amazon.com;

“Epigrams: With Parallel Latin text (Oxford World's Classics) by Martial, translated by Gideon Nisbet Amazon.com;

“Martial's Epigrams: A Selection” edited by Garry Wills Amazon.com;

“Latin Literature: An Anthology” (Penguin Classics) by Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Anthology of Roman Literature” by J. C. Mckeown Peter E. Knox Amazon.com;

“Roman Literary Culture, second edition: From Plautus to Macrobius” by Elaine Fantham | (2013) Amazon.com;

“Aeneid” (Penguin Classics) by Virgil (19 BC) Amazon.com

“Rome's Cultural Revolution” by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (2008) Amazon.com

“Augustan Culture” by Karl Galinsky (1996) Amazon.com

Ovid’s Life, Works and Success

Esteban Berché wrote in National Geographic History: Ovid was born in 43 B.C. in Sulmo (now Sulmona) 100 miles east of Rome. His letters and the Tristia (Lamentations), a five-book collection of poems written in exile, have given historians a wealth of autobiographical details. He describes himself as a natural poet from his youth: “Poetry in meter comes unbidden to me.” After a brief stint traveling and then studying in Athens, he turned his back on a political career, and went instead to Rome to become a poet. He fell in love with the city, and it embraced his poetry. [Source Esteban Berché, National Geographic History, November 26, 2019]

Completed in 16 B.C., Ovid’s first major work was the Amores, a collection of poems charting a love affair with a young woman called Corinna. In this first book of poems, Ovid employed an urbane, ironic voice. A famous poem describing a hot summer’s afternoon of lovemaking ends with the lines:

Fill in the rest for yourselves!

Tired at last, we lay sleeping.

May my siestas often turn out that way.

Some have theorized that Corinna had a real-life corollary: Fifth-century writer Sidonius Apollinaris identified her as Julia the Elder, Augustus’ daughter, and posited that Ovid enjoyed a dalliance with her. Sidonius credited that scandalous relationship for Ovid’s exile, but later historians have debunked this theory. Most commentators regard Corinna as a fictional character. Following this debut, Ovid notched up one success after another. His Heroides (Heroines) was a series of dramatic monologues centering on mythological women, including Dido, Medea, and Ariadne, who lament their mistreatment by their lovers.

A three-part work, Ars amatoria, completed around A.D. 2 was a sensation. The first two parts are a “how-to” guide for men on seducing women and keeping their love. Ovid counsels that absence makes the heart grow fonder and that asking a woman’s age is not a recipe for seduction. Part three is aimed at women and includes the suggestion that making a lover jealous isn’t such a bad idea. (Rome's Vestal Virgins were awarded privileges unavailable to other Roman women.)

In Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love), Ovid is full of advice on how to woo a lover. He urges young men: “Nor be weary of praising her looks, her shapely fingers, her small foot; even honest maids love to hear their charms extolled; even to the chaste their beauty is a care and a delight.” Ovid had struck publishing gold. His handbook gave his young audience practical tips under the guise of a formal didactic work. But despite its success, Ovid craved a more learned readership.

Already in his 40s when he completed Ars amatoria, Ovid was neither fabulously wealthy nor well connected. Inspired to write a great work like the Aeneid, Ovid wrote the Metamorphoses. “My purpose is to tell of bodies which have been transformed,” he wrote in his opening lines. He informed the readers that the theme of transformation will influence the very form of his long poem, which will “spin an unbroken thread of verse from the earliest beginnings of my world down to my own times.”

Extremely successful in its own time, the work became one of the most influential works of Western literature, inspiring numerous works of art, music, and drama. Love, lust, grief, terror, and divine punishment trigger a series of startling changes in Ovid’s retelling of 250 stories of gods and mortals. Sailors become dolphins. The sculptor Pygmalion’s kiss changes a statue into a young woman. For having spied the goddess Diana as she bathed, the hunter Actaeon is changed into a stag to be ripped apart by his hounds. In one of the Metamorphoses’ most famous passages, Daphne flees Apollo’s lustful advances and changes into a laurel tree: “Her hair grew into leaves, her arms into branches, and her feet that were lately so swift, were held by sluggish roots, while her face became the treetop. Nothing of her was left, except her shining loveliness.”

Ovid's Love Poetry

In the “Art of Love”, a carefully crafted "seducer's manual," Ovid wrote:

” Love is a kind of war, and no assignment for cowards.

Where those banners fly, heroes are always on guard.

Soft, those barracks? They know long marches, terrible weather.

Night and winter and storm, grief and excessive fatigue.

Often the rain pelts down from the drenching cloudbursts of heaven.

Often you lie on the ground, wrapped in a mantle of cold.

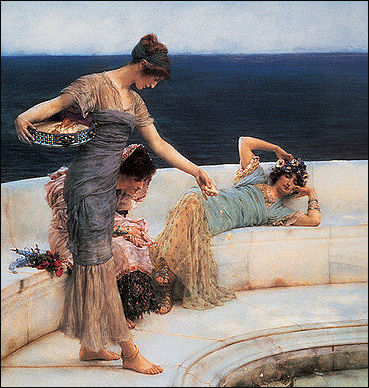

Ask Me No More by

Lawrence Alma-Tadema - If you are ever caught, no matter how well you've concealed it.

Though it is clear as the day, swear up and down it's a lie.

Don't be too abject, and don't be too unduly attentive.

That would establish your guilt far beyond anything else.

Wear yourself out if you must, and prove, in her bed, that you could not

Possibly be that good, coming from some other girl.”

Ovid tried to write his own epitaph before his death in A.D. 17. In a series of poems composed near the end of his life, he asked for these lines to be placed on his tomb:

I who lie here was a writer

Of tales of tender love

Naso the poet, done in by my

Own ingenuity.

You who pass by, should you be

A lover, may you

Trouble yourself to say that Naso’s bones

May rest softly.

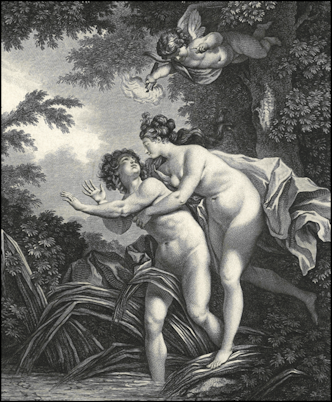

Salmacis and Hermaphroditus by Ovid

Salmacis with weak enfeebling streams

Softens the body, and unnerves the limbs,

And what the secret cause shall here be shown;

The cause is secret, but the effect is known.

[Source: poetry-archives.com]

The Naiads nurst an infant heretofore,

That Cytherea once to Hermes bore;

From both the illustrious authors of his race

The child was named; nor was it hard to trace

Both the bright parents through the infant's face;

When fifteen years, in Ida's cool retreat,

The boy had told, he left his native seat,

And sought fresh fountains in a foreign soil;

The pleasure lessened the attending toil.

With eager steps the Lycian fields he crossed,

And fields that border on the Lycian coast;

A River here he viewed so lovely bright,

It showed the bottom in a fairer light,

Nor kept a sand concealed from human sight.

The stream produced, nor slimy ooze, nor weeds,

Nor miry rushes nor the spiky reeds:

But dealt encircling moisture all around,

The fruitful banks with cheerful verdure crowned,

And kept the spring eternal on the ground

A nymph presides, nor practised in the chase,

Nor skilful at the bow, nor at the race;

Of all the blue-eyed daughters of the main.

The only stranger to Diana's train;

Her sisters, often, as 'tis said, would cry,

"Fie, Salmacis, what, always idle! Fie!

Or take thy quiver or thy arrows seize,

And mix the toils of hunting with thy ease."

But oft would bathe her in the crystal tide,

Oft with a comb her dewy locks divide;

Now in the limpid streams she viewed her face,

And drest her image in the floating glass:

On beds of leaves she now reposed her limbs,

Now gathered flowers that grew about her streams;

And then by chance was gathering, as she stood

To view the boy, and longed for what she viewed.

Fain would she meet the youth with hasty feet,

She fain would meet him, but refused to meet

Before her looks were set with nicest care,

And well deserved to be reputed fair.

"Bright youth," she cries, "whom all thy features prove

A God, and, if a God, the God of Love;

But if a mortal, blest thy nurse's breast,

Blest are thy parents, and thy sisters blest:

But, oh! how blest! how more than blest thy bride,

Allied in bliss, if any get allied:

If so, let mine the stolen enjoyment be;

If not, behold a willing bride to me."

The boy knew nought of love, and, touched with shame,

He strove, and blushed, but still the blush became;

In rising blushes still fresh beauties rose;

The sunny side of fruit such blushes shows,

And such the moon, when all her silver white

Turns in eclipses to a ruddy light.

The Nymph still begs, if not a nobler bliss,

A cold salute at least, a sister's kiss;

And now prepares to take the lovely boy

Between her arms. He, innocently coy,

Replies, "Oh leave me to myself alone,

You rude, uncivil nymph, or I'll begone."

"Fair stranger then," says she; "it shall be so";

And, for she feared his threats, she feigned to go;

But hid within a covert's neighboring green,

She kept him still in sight, herself unseen.

The boy now fancies all the danger o'er,

And innocently sports about the shore,

Playful and wanton to the stream he trips,

And dips his foot, and shivers as he dips,

The coolness pleases him, and with eager haste

His airy garments on the banks he cast;

His godlike features and his heavenly hue,

And all his beauties were exposed to view.

His naked limbs the nymph with rapture spies,

While hotter passions in her bosom rise,

Flush in her cheeks, and sparkle in her eyes.

She longs, she burns to clasp him in her arms,

And loves, and sighs, and kindles at his charms.

Now all undrest upon the banks he stood,

And clapt his sides and leapt into the flood:

His lovely limbs the silver waves divide,

His limbs appear more lovely through the tide;

As lilies shut within a crystal case,

Receive a glossy lustre from the glass.

"He's mine, he's all my own," the Naiad cries,

And flings off all, and after him she flies.

And now she fastens on him as he swims,

And holds him close, and wraps about his limbs.

The more the boy resisted and was coy,

The more she kissed and clipt the strippling boy.

So when the wriggling snake is hatched on high

In eagle's claws, and hisses in the sky,

Around the foe his twirling tail he flings,

And twists her legs, and writhes about her wings.

The restless boy still obstinately strove

To free himself and still refused her love.

Amidst his limbs she kept her limbs entwined,

"And why, coy youth," she cries, "why thus unkind!

Oh, may the Gods thus keep us ever joined!

Oh, may we never, never part again!"

So prayed the nymph, nor did she pray in vain:

For now she finds him, as his limbs she prest,

Grow nearer still, and nearer to her breast;

Till, piercing each the other's flesh, they run

Together, and incorporate in one:

Last in one face are both their faces joined,

As when the stock and grafter twig combined

Shoot up the same, and wear a common mind:

Both bodies in a single body mix,

A single body with a double sex.

The boy, thus lost in woman, now surveyed

The river's guilty stream, and thus he prayed.

(He prayed, but wondered at his softer tone,

Surprised to hear a voice but half his own.)

You parent gods, whose heavenly names I bear,

Hear your Hermaphrodite, and grant my prayer;

Oh, grant that--whom so'er these streams contain,

If man he entered, he may rise again

Supple, unsinewed, and but half a man!

The heavenly parents answered, from on high

Their two-shaped son, the double votary;

Then gave a secret virtue to the flood,

And tinged its source to make his wishes good.

Ovid Exiled from Rome After Angering Augustus

Esteban Berché wrote in National Geographic History: By age 50 Ovid had reached the peak of his popularity. His groundbreaking style had established him as one of the most popular poets in Rome. But it was just as his fortunes were riding high that disaster broke. In A.D. 8, as Ovid was garnering praise for the Metamorphoses, the emperor Augustus decided to send him into exile. [Source Esteban Berché, National Geographic History, November 26, 2019]

Ovid lived the rest of his years in Tomis. His petitions to the emperor were all in vain. After Augustus’ death in A.D. 14, Ovid tried to get his successor Tiberius to commute his sentence, but the new emperor was impervious to the continued pleas of both the poet and his wife Fabia. The Roman love poet died in A.D. 17, far from the city where he had made his name, and which he had loved so dearly.

Scholars still have not pinpointed all the reasons why Augustus wanted Ovid exiled. The poet attributed his punishment to “carmen et error”—“a poem and an error.” Most historians agree the “poem” was the Ars amatoria, whose rakish indifference to social norms was at odds with the new imperial morality Augustus was promoting. As chief priest, the emperor was guardian of laws and customs (curator legum et morum) and was eager to restore traditional social norms.

In A.D. 8, the year of Ovid’s banishment, however, the Ars amatoria was more than five years old. Historians largely agree that while the poem might have served as extra evidence of Ovid’s undesirability in the eyes of Augustus, it was a secondary cause for his banishment. The real reason for Ovid’s exile was the “error,” references to which are scattered through Ovid’s later writing. Scanning these texts for clues, scholars have found several hints as to what the “error” might have been. The poet never spells it out, but states that it was unpremeditated, the result of a foolish mistake.

Numerous hypotheses have been put forward. American scholar John C. Thibault’s 1964 book, The Mystery of Ovid’s Exile, studies medieval writings that speculate on Ovid’s error. Among the most dramatic are that Ovid knew of an incestuous affair between Augustus and his daughter Julia, or that Ovid had a dalliance with Livia, the emperor’s wife. The 20th-century British Ovid scholar Peter Green proposes that the error was not moral, but political. A very delicate theme at the time was the question of Augustus’ succession. If Ovid had gossiped about certain political factions, his indiscretions (combined with the salaciousness of his earlier erotic poetry) could have been enough to seal his fate.

Catullus

Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (c. 85- c. 54 B.C.) was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic. John Porter of the University of Saskatchewan wrote: “We know little about Catullus beyond what he tells us in his poems. He was born in Verona (in northern Italy) and thus, like most of Rome's distinguished poets, was a provincial — an outsider. Although he frequently jokes about his poverty, it is clear that he came from a wealthy equestrian family. His father was prominent (and rich) enough to be on friendly terms with Julius Caesar. (We know this from the life of Caesar composed by the historian Suetonius, who records that, although Catullus had deeply offended Caesar with his little piece about Mamurra [see poem 29], once the poet had apologized Caesar immediately resumed his habit of enjoying the hospitality of Catullus' father.) Moreover, the poems show that Catullus himself, his brother, and his friends (people like Veranius and Fabullus in poems 28 and 47) have foreign business interests and have served in the official retinues (the cohorts) of provincial governors in the east. Catullus is very much an equestrian in outlook. For all of his ribaldry and his flouting of authority, he is deeply conservative in his views, with an abiding concern for the bottom line. His easy familiarity with Greek culture and literature suggests that he has received the traditional education of a wealthy Roman of his day. [Source: John Porter, University of Saskatchewan homepage.usask.ca ***]

“The only secure date that we have for Catullus is 57-56 B.C., during which time he was in Bithynia on the staff of the provincial governor C. Memmius (a son-in-law of Sulla). Given the normal course of the average equestrian's career, this would suggest that Catullus was born c. 82 B.C. All of his other datable poems also fall in the period, roughly, of the early- to mid-50s B.C. The absence of any references to events later than the mid-50s perhaps confirms the ancient biographical tradition that Catullus died young, at about the age of 30 (i.e., c. 54 B.C.). ***

“Catullus' 116 poems are preserved in a single collection that seems to be the work of an ancient editor. Poems 1-60 are shorter pieces, for the most part, written in a variety of meters, on a variety of topics (love poems, attacks against enemies, witty observations on contemporary mores, short hymns), and in a variety of tones. Poems 61-68 are longer pieces, again in a variety of meters and on a variety of topics (from wedding poems to a particularly elaborate example of an epyllion or "mini-epic" in the style of the Hellenistic poets [on which, see below]). Poems 69ff. are shorter pieces of varying length composed in elegiac couplets — a weightier, more reflective meter than those of poems 1-60. The subject matter of these poems parallels that of poems 1-60 for the most part, but often in a more somber or brooding tone. This is particularly true of the Lesbia poems in this part of the collection.” ***

Catullus (c.84-c.54 B.C.): Poems Saskatchewan, Internet Archive web.archive.org;

Catullus (c.84-c.54 B.C.): Complete Poems trana. A.S. Kline, unexpurgated translation, Poetry in Motion, poetryintranslation.com/

Catullus (c.84-c.54 B.C.): The Carmina trans. Richard Burton Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Catullus (c.84-c.54 B.C.): Poems and Fragments trans. Robinson Ellis Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

See Separate Article: SEX POETRY FROM ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Catullus Poems

Poem 29

“Who can see this? Who can endure it,

except for the depraved, the gluttonous, the gamblers —

Mamurra 1 holding in his possession all the sleek wealth that Gallia Comata 2

used to have, and that of farthest Britain?

Pathic Romulus, will you see this and endure it?

And now will that fellow do the rounds of all

the bedrooms, proud and prodigal,

like a white little dove or an Adonis?

Catullus saved from shipwreck

Pathic Romulus, will you see this and endure it?

You're depraved, a glutton, and a gambler.

Was it for this, o sole commander,

that you busied yourself on the farthest island of the setting sun,

that this fucked-out prick of yours might

devour twenty or thirty million sesterces?

What is misguided generosity but this?

Had he plowed through too few fortunes? Not gobbled down enough?

First he demolished his paternal wealth,

then the Pontic plunder 3; third came that from

Spain — all the riches gold-bearing Tagus knew, 4

and now there's fear for Gaul and Britain.

Why, dammit, do you cherish this fellow so? What skill's he got,

other than wolfing down rich patrimonies?

Was it for this, o most pius men of Rome,

father and son-in-law, that you wrought havoc on the world?

[Source: translated by John Porter, University of Saskatchewan]

Poem 93

“I have no real desire, Caesar, to wish to seek your favor,

or to know whether you are white or black. 5

Poem 47

“Porcius and little Socrates, Piso's two

left hand men, blight and bane of the earth —

have that Priapus 12 and his hard-on placed you ahead in favor

to my little Veranius and Fabullus?

Do you hold lavish drinking parties with all the finery

in the middle of the day, while my friends

stand on the public streets seeking dinner invitations?

Notes: 1 A Roman eques who served under both Pompey and Caesar and was one of Caesar's chief administrators in Gaul. 2 I.e. Transalpine Gaul. 3 The spoils from Pompey's defeat of Mithridates (63 B.C.). 4 From Caesar's campaign as propraetor in Spain in 61 B.C. 5 A colloquial way of indicating complete ignorance and indifference about somebody. 12 A Roman vegetation deity commonly portrayed with a large erect penis.

Poems by Catallus Addressed to Lesbia

Lesbia was the literary pseudonym used by Catallus to refer to his lover. She is traditionally identified with Clodia, the wife of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer and sister of Publius Clodius Pulcher. Her conduct and motives are criticized in Cicero's speech Pro Caelio, delivered in 56 B.C.. Lesbia is the subject of 25 of Catullus' 116 surviving poems. They display a wide range of emotions, ranging from tender love (e. g. Catullus 5, Catullus 7), to sadness and disappointment (e.g. Catullus 72), and to bitter sarcasm (e.g. Catullus 8), following the ups and downs of her relationship with Catullus. [Source: Wikipedia]

Poem 2

Sparrow, o, Lesbia’s sweet bird

whom she keeps near to stroke

at her bosom, to whom with delight

she offers a restless finger,

prodding for bites, tiny wounds,

if ever my fiery lady needs some

distraction from passion’s sweet pain…

o! that I could play with you myself

little sparrow, you would free

my thoughts from despair.

[Source: intranslation.brooklynrail.org]

Lesbia by John Reinhard Weguelin

Poem 5

Lesbia, come, let us live and love, and be

deaf to the vile jabber of the ugly old fools,

the sun may come up each day but when our

star is out…our night, it shall last forever and

give me a thousand kisses and a hundred more

a thousand more again, and another hundred,

another thousand, and again a hundred more,

as we kiss these passionate thousands let

us lose track; in our oblivion, we will avoid

the watchful eyes of stupid, evil peasants

hungry to figure out

how many kisses we have kissed.

Poem 75

Lesbia, I am mad:

my brain is entirely warped

by this project of adoring

and having you

and now it flies into fits

of hatred at the mere thought of your

doing well, and at the same time

it can’t help but seek what

is unimaginable–

your affection. This it will go on

hunting for, even if it

means my total and utter annihilation.

Poem 79

Lesbius is a beauty. Why? Well,

because sister Lesbia adores him

–and far more than you,

old Catullus,

with your entire family to boot. And

nevertheless this pretty guy

would certainly sell all your relatives,

and you too, Catullus, into slavery

in order to buy the kisses

of several boy-whores.

Another translation of Poem 79

“Lesbius is pretty, who denies it? He whom Lesbia loves

more than you and your whole family line together, Catullus.

But all the same, that "pretty" Lesbius would sell off Catullus

and his line 14 for just three kisses 15 from his friends.

Notes: 14 I.e. into slavery. 15 I.e. for any petty motive, without a thought. (The Romans commonly greeted one another with a kiss.)

Catallus on Male Friendship in Ancient Rome

Catullus has some verses of real feeling about “male friendship”:

Quintius, if 'tis thy wish and will

That I should owe my eyes to thee,

Or anything that's dearer still,

If aught that's dearer there can be; \=\

[Source: translation Trans. by J. W. Baylis]

“Then rob me not of that I prize,

Of the dear form that is to me,

Oh I far far dearer than my eyes,

Or aught, if dearer aught there be."

Catullus, translated by Hon. F. Lamb, 1821. \=\

“If all complying, thou would'st grant

Thy lovely eyes to kiss, my fair,

Long as I pleased; ohl I would plant

Three hundred thousand kisses there. \=\

“Nor could I even then refrain,

Nor satiate leave that fount of blisses,

Tho' thicker than autumnal grain

Should be our growing crop of kisses." \=\

“Long at our leisure yesterday

Idling, Licinius, we wrote

Upon my tablets verses gay,

Or took our turns, as fancy smote,

At rhymes and dice and wine. \=\

“But when I left, Licinius mine,

Your grace and your facetious mood

Had fired me so, that neither food

Would stay my misery, nor sleep

My roving eyes in quiet keep.

But still consumed, without respite,

I tossed about my couch in vain

And longed for day-if speak I might,

Or be with you again. \=\

“But when my limbs with all the strain

Worn out, half dead lay on my bed,

Sweet friend to thee this verse I penned,

That so thou mayest condescend

To understand my pain. \=\

“So now, Licinius, beware!

And be not rash, but to my prayer

A gracious hearing tender;

[96] Lest on thy head pounce Nemesis:

A goddess sudden and swift she is-

Beware lest thou offend her." \=\

Horace (65-8 B.C.)

Horace Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace, 65-8 B.C.) was one of the Roman Empire's greatest poets and the founder of a philosophy he called “idealized common sense.” He is the source of many proverbs and quoted phrases such as "Carpe diem" ("Seize the day")...”put no trust in the morrow.”

Horace was bald, fat, and "touched with cowardice and torn between the pleasures of the country and need crawl at court." He was a failed soldier who once took off running in the opposite direction when his commander ordered him to charge. He later became a petty bureaucrat which gave him enough time to write poetry. His “ Satires” and “ Epistles” were classic commentaries on the Augustan Age.

On the politics of Horace, David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “ Horatius Flaccus fought at Philippi in 42 B.C., as a young man, for Brutus against the triumvirs Octavian and Antony. Many critics have found a shift in Horace's attitude to Augustus and the principate between the first three books of the Odes, published in a body around 23 B.C., and the fourth book, published around 13 B.C.; this comes not only from internal evidence, but also from the fact of Horace's authorship of the Carmen Saeculare, a hymn commissioned by Augustus for performance in 17 B.C. Is this supposition justified, or is there more to the political element in Horace's poetry than propaganda or toadyism? It is all too easy to paint Horace as a shameless glorifier of Augustus; the task is to find whether that unmistakeable position goes below the surface of the poems, or whether it is subtly undercut. In what sense might it be said that Augustus controlled influential forms of public discourse such as the poems of Horace, actually or indirectly or not at all? Why does Horace consistently advocate further additions to the Roman empire, especially expeditions of conquest against the Parthians and Britons? How satisfied was he with Augustus' foreign policy decisions, and is any dissatisfaction expressed in such a way as to be inoffensive?” [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Horace (5-8 B.C.): Secular hymn, and Vergil (70-19 B.C.): Aeneid, VI.ii.789-800, 847-853.

Horace (5-8 B.C.): We All Must Die WSU, Internet Archive web.archive.org;

Horace’s Poems

Describing his life's work in his third book of Odes” , Horace wrote:

I have erected a monument more lasting

than bronze

And taller than the regal peak of the

pyramids...

I shall never completely die.”

In another ode, Horace wrote:

” Happy the man, and happy he alone.

He, who can call today his own;

He who, secures within, can say.

Tomorrow do they worst, for I have

lived today” .

Horace: We All Must Die

Augustus's death

Alas, dear friend, the fleeting years

In everlasting circles run,

In vain you spend your vows and prayers,

They roll, and ever will roll on.

[Source: Translated by Samuel Johnson (1760)]

“Should hecatombs (1) each rising morn

On cruel Pluto's (2) altar dye,

Should costly loads of incense burn,

Their fumes ascending to the sky:

“You could not gain a moment's breath

Or move the haughty king below

Nor would inexorable death

Defer an hour the fatal blow.

“In vain we shun the din of war,

And terrors of the stormy main, (3)

In vain with anxious breasts we fear

Unwholesome Sirius' (4) sultry reign;

“We all must view the Stygian flood (5)

That silent cuts the dreary plains,

And Cruel Danaus' bloody brood (6)

Condemned to everduring pains.

“Your shady groves, your pleasing wife,

And fruitful fields, my dearest friend,

You'll leave together with your life:

Alone the cypress (7)

“After your death, the lavish heir

Will quickly drive away his woe;

The wine you kept with so much care

Along the marble floor shall flow.

Notes: 1) Extravagant sacrifices, consisting of a hundred oxen. 2) The Lord of the Dead. 3) Ocean. 4) When the Dog Star Sirius was in the ascendency in August it was thought to exert a harmful influence on human health. 5) The Styx, the river which the dead crossed into on their way to Hades. 6) Danaus persuaded his fifty daughters to kill their husgbands because he was feuding with their new father-in-law. The women were punished in Hades by having continually carry water in leaking vessels so that their task would never be finished. 7) The cypress, common in Italy, is traditonally associated with mourning.

Horace’s Hymn for Augustus’s Secular Games

Horace “Secular Hymn” for Augustus’s Secular Games goes:

“Phoebus! and Dian, you whose sway,

Mountains and woods obey!

Twin glories of the skies, forever worshiped, hear!

Accept our prayer this sacred year

When, as the Sibyl's voice ordained

For ages yet to come,

Pure maids and youths unstained

Invoke the Gods who love the sevenfold hills of Rome.

arean

“All bounteous Sun!

Forever changing, and forever one!

Who in your lustrous car bear'st forth light,

And hid'st it, setting, in the arms of Night,

Look down on worlds outspread, yet nothing see

Greater than Rome, and Rome's high sovereignty.

You Ilithyia, too, whatever name,

Goddess, you do approve,

Lucina, Genitalis, still the same

Aid destined mothers with a mother's love;

“Prosper the Senate's wise decree,

Fertile of marriage faith and countless progeny!

As centuries progressive wing their flight

For you the grateful hymn shall ever sound;

Thrice by day, and thrice by night

For you the choral dance shall beat the ground.

“Fates! whose unfailing word

Spoken from lips Sibylline shall abide,

Ordained, preserved and sanctified

By Destiny's eternal law, accord

To Rome new blessings that shall last

In chain unbroken from the Past.

Mother of fruits and flocks, prolific Earth!

Bind wreaths of spiked corn round Ceres's hair:

And may soft showers and Jove's benignant air

Nurture each infant birth!

“Lay down your arrows, God of day!

Smile on your youths elect who singing pray.

You, Crescent Queen, bow down your star-crowned head

And on your youthful choir a kindly influence shed.

If Rome be all your work — if Troy's sad band

Safe sped by you attained the Etruscan strand,

A chosen remnant, vowed

To seek new Lares, and a changed abode —

Remnant for whom thro Ilion's blazing gate

Aeneas, orphan of a ruined State,

Opened a pathway wide and free

To happier homes and liberty: —

Ye Gods! If Rome be yours, to placid Age

Give timely rest: to docile Youth

Grant the rich heritage

Of morals, modesty, and truth.

On Rome herself bestow a teaming race

Wealth, Empire, Faith, and all befitting Grace.

“Vouchsafe to Venus' and Anchises' heir,

Who offers at your shrine

Due sacrifice of milk-white kine,

Justly to rule, to pity and to dare,

To crush insulting hosts, the prostrate foeman spare

The haughty Mede has learned to fear

The Alban axe, the Latian spear,

And Scythians, suppliant now, await

The conqueror's doom, their coming fate.

Honor and Peace, and Pristine Shame,

And Virtue's oft dishonored name,

Have dared, long exiled, to return,

And with them Plenty lifts her golden horn.

“Augur Apollo! Bearer of the bow!

Warrior and prophet! Loved one of the Nine!

Healer in sickness! Comforter in woe!

If still the templed crags of Palatine

And Latium's fruitful plains to you are dear,

Perpetuate for cycles yet to come,

Mightier in each advancing year,

The ever growing might and majesty of Rome.

You, too, Diana, from your Aventine,

And Algidus= deep woods, look down and hear

The voice of those who guard the books Divine,

And to your youthful choir incline a loving ear.

“Return we home! We know that Jove

And all the Gods our song approve

To Phoebus and Diana given;

The virgin hymn is heard in Heaven.”

Sulpicia: The Only Roman Poetess Whose Poems Have Survived

Sulpicia (Late 1st Cent. A.D.) is the only surviving Roman female poet. According to Diotama: “Many women, we know, wrote poetry in ancient Rome. The works of only one have survived. These six poems by Sulpicia, the niece of the distinguished statesman and patron of letters Valerius Messalla Corvinus, allow us to hear an aristocratic female voice from the late first century B.C. and the Augustan milieu of Horace and Vergil. Sulpicia's work has been handed down as part of the Corpus Tibullianum, a collection of poems by Tibullus and other poets affiliated with Messalla. Poems Diotima, Internet Archive web.archive.org

Sulpicia

Sulpicia: Six Poems:

At last. It's come. Love,

the kind that veiling

will give me reputation more

than showing my soul naked to someone.

I prayed to Aphrodite in Latin, in poems;

she brought him, snuggled him

into my bosom.

Venus has kept her promises:

let her tell the story of my happiness,

in case some woman will be said

not to have had her share.

I would not want to trust

anything to tablets, signed and sealed,

so no one reads me

before my love —

but indiscretion has its charms;

it's boring

to fit one's face to reputation.

May I be said to be

a worthy lover for a worthy love.

[Source: translation by Lee Pearcy, Diotima]

“Birthday's here and I hate it —

of all the days to be spent in gloom

out in the dreary country

without Cerinthus.

What is sweeter than the city?

Is a house in the country

on the banks of that frigid stream in Arretine country,

any place for a girl?

Now Uncle Messalla, do take a rest —

you've always looked after me too well.

There are times, you know, when travel's

a bad idea.

I'VE BEEN KIDNAPPED I'VE LEFT BEHIND

MY MIND MY FEELING VIOLENCE

DOESN'T LET ME BE MY OWN

MISTRESS.

Alma Tadema's Silver Favourites “You know the dreary trip contemplated for a girl?

Now I can be at Rome for your birthday.

May that day be celebrated by us all,

which now comes, perchance, as no surprise to you.

“Thank you for taking such pains over me,

for keeping me from making a fool of myself.

I do hope you enjoy the bimbo.

Her flashy clothes

do cast a subtly shabby light on

SVLPICIA SERVI FILIA.

(They are a little worried about me,

afraid I might trip up,

marry a nobody.)

“Do you think kindly of your girl, Cerinthus,

now that a fever attacks my limbs?

I wouldn't wish to get well except on one condition:

that I could think you wished it too.

But what would be the good in getting well, if you

can bear my sickness with unfluttered heart?

“May I never be, o dawn of my life, as warm a care to you

as I seem to have been a few days ago,

if — fool that I am — I've done anything in all my short life

that I might admit to regretting more

than leaving you alone last night —

passionate only to hide my passion.

Martial and His Sexually-Explicit Epigrams

On Marcus Valerius Martialis, Steve Coates wrote in the New York Times, “You have to be impressed by a plucky Spanish provincial, in the dangerous days of Nero and Domitian, who could manage to earn a handsome living writing dirty poems for the urban sophisticates of ancient Rome. [Source: Steve Coates, December 12, 2008]

Arriving in Rome around A.D. 64, Martial spent much of the next four decades composing short topical verse about life in the big city, an urban panorama as broad, as varied and as full of depraved humanity as any to have survived from classical times. In conventional but nimble Latin meters, he wrote gory epigrams about the Colosseum, sycophantic ones to flatter the ruler of the day, tender ones about such topics as a slave girl’s early death and, above all, comic ones aimed squarely at Roman society’s foibles. Preoccupations including comb-overs, stingy hosts, medical quacks, the poetry racket, the futility of cosmetics, consumptive heiresses and one-eyed women lend his books the ambience of a front-row seat at the Roman carnival.

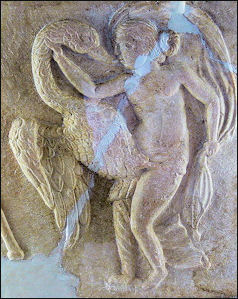

sex with a goose Modern readers, however, are drawn to Martial mostly for his scorpion-tailed epigrams of sexual invective, written, limerick- and graffiti-like, as raunchy entertainment. Even by today’s standards, many are grotesquely obscene; Martial takes us down some of Rome’s sleaziest streets (“I write, I must confess, for dirtier readers, / My verse does not attract the nation’s leaders”).

If Martial’s poems weren’t saintly, though, they were all in good fun (“My poetry is filthy — but not I,” he insisted). His targets were types, not real people, and many of his outrageous sketches, it has been rightly said, “come no closer to plausible reality than a Victorian Punch cartoon.” In this spirit, Martial riffs endlessly on prostitution, marital infidelity, oral sex, pederasty, exhibitionism, unapproved modes of homosexuality, and incest (“Of course we know he’ll never wed. / What? Put his sister out of bed?”). Roman sexual humor, it seems, when not simply gross-out comic description of intimate body parts — Martial wrote a notorious poem involving a loquacious vagina — hinged largely on the question of who might be on the passive end of any copulatory squirming (“I thought “twas you that played the man / But find receive is all you can”).

In a review of “Martial’s Epigrams” translated by Garry Wills, Coats wrote in the New York Times, “In the case of lines far more lubriciously explicit than these, Wills embraces the Roman poet’s copious Latin obscenities in tumescent Anglo-Saxon translations, and in this sense certainly conveys the authentic Martial. He suggests that his happy-go-lucky rhyming verse and dogged meters work toward the same end, preserving some of the strict formality of Martial’s elegiacs and hendecasyllables. But in fact, Wills’s commitment to rhyme, not a significant concern for Latin poets, forces his syntactical hand and allows much of the real Martial to fall between the cracks. One neat example is a two-line poem that Wills translates: “Her teeth look whiter than they ought. / Of course they should — the teeth were bought.” A prose version reveals that Martial was able to insult not one woman but two in the same space: “Thais’s teeth are black, Laecania’s snow-white. The reason? The latter has ones she bought, the former her own.”

Book: “Martial’s Epigrams” translated and with an introduction by Garry Wills (Viking, 2008)

See Separate Article: SEX POETRY FROM ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024