ACHAEMENID PERSIAN EMPIRE (550–330 B.C.)

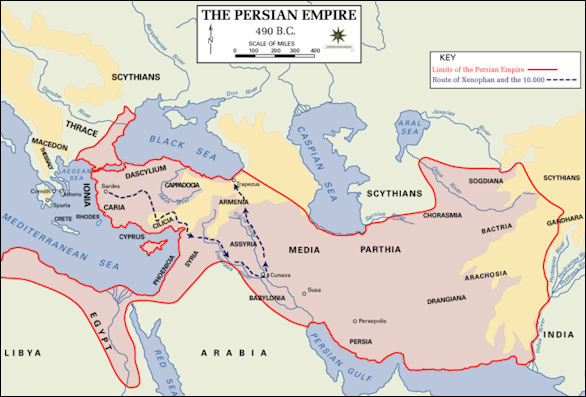

Cyrus and PerspolisThe Achaemenid Persian empire was the largest that the ancient world had seen, extending from Anatolia and Egypt across western Asia to northern India and Central Asia. Much of our evidence for Persian history is dependent on contemporary Greek sources and later classical writers, whose main focus is the relations between Persia and the Greek states, as well as tales of Persian court intrigues, moral decadence, and unrestrained luxury. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

The Neo-Babylonians (Chaldeans) gave up Babylon without a fight in 539 B.C. to the Persian king Cyrus. By 546 B.C., Cyrus had defeated Croesus, the Lydian king of fabled wealth, and had secured control of the Aegean coast of Asia Minor, Armenia, and the Greek colonies along the Levant . Moving east, he took Parthia (land of the Arsacids, not to be confused with Parsa, which was to the southwest), Chorasmis, and Bactria. He besieged and captured Babylon in 539 and released the Jews who had been held captive there, thus earning his immortalization in the Book of Isaiah. When he died in 529, Cyrus's kingdom extended as far east as the Hindu Kush in present-day Afghanistan. [Source: Library of Congress, December 1987 *]

His successors were less successful. Cyrus's unstable son, Cambyses II, conquered Egypt but later committed suicide during a revolt led by a priest, Gaumata, who usurped the throne until overthrown in 522 by a member of a lateral branch of the Achaemenid family, Darius I (also known as Darayarahush or Darius the Great). Darius attacked the Greek mainland, which had supported rebellious Greek colonies under his aegis, but as a result of his defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 was forced to retract the limits of the empire to Asia Minor. *

The Achaemenids thereafter consolidated areas firmly under their control. It was Cyrus and Darius who, by sound and farsighted administrative planning, brilliant military maneuvering, and a humanistic worldview, established the greatness of the Achaemenids and in less than thirty years raised them from an obscure tribe to a world power.*

Standard of Cyrus the Great The quality of the Achaemenids as rulers began to disintegrate, however, after the death of Darius in 486. His son and successor, Xerxes, was chiefly occupied with suppressing revolts in Egypt and Babylonia. He also attempted to conquer the Greek Peloponnesus, but encouraged by a victory at Thermopylae, he overextended his forces and suffered overwhelming defeats at Salamis and Plataea. By the time his successor, Artaxerxes I, died in 424, the imperial court was beset by factionalism among the lateral family branches, a condition that persisted until the death in 330 of the last of the Achaemenids, Darius III, at the hands of his own subjects.*

Achaemenid Persian dynasty

Cyrus II the Great: 559–530 B.C.

Cambyses II: 530–522 B.C.

Darius I: 521–486 B.C.

Xerxes: 486–465 B.C.

Artaxerxes I: 465–424 B.C.

Darius II: 423–405 B.C.

Artaxerxes II: 405–359 B.C.

Artaxerxes III: 358–338 B.C.

Artaxerxes IV: 338–336 B.C.

Darius III: 336–330 B.C.

[Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Books: Briant, Pierre From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2002. Wiesehöfer, Josef Ancient Persia: From 550 B.C. to 650 AD. London: I.B. Tauris, 1996.

Achaemenid Rule

The Achaemenids were enlightened despots who allowed a certain amount of regional autonomy in the form of the satrapy system. A satrapy was an administrative unit, usually organized on a geographical basis. A satrap (governor) administered the region, a general supervised military recruitment and ensured order, and a state secretary kept official records. The general and the state secretary reported directly to the central government. The twenty satrapies were linked by a 2,500-kilometer highway, the most impressive stretch being the royal road from Susa to Sardis, built by command of Darius. Relays of mounted couriers could reach the most remote areas in fifteen days. Despite the relative local independence afforded by the satrapy system however, royal inspectors, the "eyes and ears of the king," toured the empire and reported on local conditions, and the king maintained a personal bodyguard of 10,000 men, called the Immortals. [Source: Library of Congress, December 1987 *]

The language in greatest use in the empire was Aramaic. Old Persian was the "official language" of the empire but was used only for inscriptions and royal proclamations. The Achaemenid art and architecture found there is at once distinctive and also highly eclectic. The Achaemenids took the art forms and the cultural and religious traditions of many of the ancient Middle Eastern peoples and combined them into a single form. This Achaemenid artistic style is evident in the iconography of Persepolis, which celebrates the king and the office of the monarch. *

Darius revolutionized the economy by placing it on a silver and gold coinage system. Trade was extensive, and under the Achaemenids there was an efficient infrastructure that facilitated the exchange of commodities among the far reaches of the empire. As a result of this commercial activity, Persian words for typical items of trade became prevalent throughout the Middle East and eventually entered the English language; examples are, bazaar, shawl, sash, turquoise, tiara, orange, lemon, melon, peach, spinach, and asparagus. Trade was one of the empire's main sources of revenue, along with agriculture and tribute. Other accomplishments of Darius's reign included codification of the data, a universal legal system upon which much of later Iranian law would be based, and construction of a new capital at Persepolis, where vassal states would offer their yearly tribute at the festival celebrating the spring equinox. In its art and architecture, Persepolis reflected Darius's perception of himself as the leader of conglomerates of people to whom he had given a new and single identity.

Persian Empire at its height

Persian Governance

The ancient Persians established the first empire with a common language, coinage and a postal and road system and religious tolerance. The privileges they gave the Jews is regarded as an example of their tolerances, which they used effectively to maintain a large and stable empire.

The Persian Empire was ruled by a government and bureaucracy and army, with Persians holding the chief positions. Darius headed an international bureaucracy with Persian governors that ruled over 20 provinces. An official called the King’s Eye regularly visited the provinces and reported back to the king. The governors supplied the king with soldiers, tributes and taxes.

Darius standardized coins, weights and measures. Gold coins were minted for imperial transactions. Gold poured in from India, which Herodotus said was produced by a species of ants” — huge ants, smaller than dogs but larger than foxes.”

The Persians were famous for exploiting the resources and styles of civilizations of the peoples it ruled. Subjects were required to follow the strict “laws of the Medes and Persians, which altereth not.” Those who broke the laws were severely punished.

Persian Military

Persia armies relied on chariots and long bows and numbers. Their horses were about half the size of modern horses. Soldiers were provided by the governors in the provinces. Ships and sailors were provided by coastal provinces and colonies such as Egypt, Phoenicia and coastal Asia Minor.

The army of Darius III was comprised of 250,000 soldiers from 24 different subject or mercenary armies including Indian, Bactrians, Dahae, Medes, Mardians, Babylonians, Parthians and Arachosians. Darius's force was lead by 40,000 Persian cavalry men. He even had some fighting elephants at his disposal.

The Persian mace was a formidable weapon. The epsilon-axe had a blade attached to a handle by rivets on the three inner tangs. Bronzes from Luristan in the Zagros mountains, from tombs dated between 600 and 1000 B.C., include a bit that indicates that horses were used. A shield boss, probably mounted in the center of the shield, features an indentation barely visible on the lower edge that may have been made from the blow of an axe. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

Behistun Inscription

Rise of the Achaemenid Persian Empire

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The formation of the Achaemenid Persian empire “began in 550 B.C., when King Astyages of Media, who dominated much of Iran and eastern Anatolia (Turkey), was defeated by his southern neighbor Cyrus II ("the Great"), king of Persia (r. 559–530 B.C.). This upset the balance of power in the Near East.[Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.)", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The Lydians of western Anatolia under King Croesus took advantage of the fall of Media to push east and clashed with Persian forces. The Lydian army withdrew for the winter but the Persians advanced to the Lydian capital at Sardis, which fell after a two-week siege. The Lydians had been allied with the Babylonians and Egyptians and Cyrus now had to confront these major powers. The Babylonian empire controlled Mesopotamia and the eastern Mediterranean. In 539 B.C., Persian forces defeated the Babylonian army at the site of Opis, east of the Tigris. Cyrus entered Babylon and presented himself as a traditional Mesopotamian monarch, restoring temples and releasing political prisoners. The one western power that remained unconquered in Cyrus' lightning campaigns was Egypt. It was left to his son Cambyses to rout the Egyptian forces in the eastern Nile Delta in 525 B.C. After a ten-day siege, Egypt's ancient capital Memphis fell to the Persians.

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “King Cyaxeres of Media died in 585 and was succeeded by his son Astyages (585-550). Among the formerly migratory Aryan groups that composed part of the empire was the tribe from Parsua, the land west of Lake Urmia, now settled in the area east of the Persian Gulf called Parsa, after their former homeland. By the middle of the seventh century, tribal holdings had expanded and incorporated the Anshan area north of the gulf. At the beginning of the sixth century, King Cambyses I, known as "King of Anshan," a petty prince within the Median Empire, married the daughter of the emperor, King Astyages, and the son born of this union was Cyrus, destined to become "the Great." [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

Decline of the Neo-Babylonians and the Rise of Persia

Morris Jastrow said: “On the death of Nebuchadnezzar, in 561 B.C., the decline of the neo-Babylonian empire sets in and proceeds rapidly, as in Assyria the decline began after the death of her grand monargue. Internal dissensions and rivalries among the priests of Babylon and Sippar divided the land. The glory of the Chaldean revival was of short duration, and in the year 539 B.C., Nabonnedos, the last native king of Babylon, was forced to yield to the new power coming from Elam. It was the same old enemy of the Euphrates Valley, only in a new garb, that appeared when Cyrus stood before the gates of Babylon. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Nabonnedos gave the weight of his influence to the priestly party of Sippar. In revenge, the priests of Babylon abetted the advance of Cyrus who was hailed by them as the deliverer of Marduk. With scarcely an attempt at resistance, the capital yielded, and Cyrus marched in triumph to the temple of Marduk. The great change had come so nearly imperceptibly that men hardly realised that with Cyrus on the throne of Babylon a new era was ushered in. In the wake of Cyrus came a new force in culture, accompanied by a religious faith that, in contrast to the Babylonian-Assyrian polytheism with its elaborate cult and ritual, appeared rationalistic—almost coldly rationalistic. Far more important than the change of government from Chaldean to Persian control of the Euphrates Valley and of its dependencies was the conquest of the old Babylonian religion by Mazdeism or Zoroastrianism, which, though it did not become the official cult, deprived the worship of Marduk, Nebo, Shamash, and the other gods of much of its vitality.

Persians capture Babylon

Herodotus on Persia

Herodotus wrote in Book IV of' Histories, “The Persians inhabit a country upon the southern or Erythraean sea; above them, to the north, are the Medes; beyond the Medes, the Saspirians; beyond them, the Colchians, reaching to the northern sea, into which the Phasis empties itself. These four nations fill the whole space from one sea to the other. [Source: Herodotus’s “Histories”, Book IV, Written 440 B.C., translated by George Rawlinson]

“West of these nations there project into the sea two tracts which I will now describe; one, beginning at the river Phasis on the north, stretches along the Euxine and the Hellespont to Sigeum in the Troas; while on the south it reaches from the Myriandrian gulf, which adjoins Phoenicia, to the Triopic promontory. This is one of the tracts, and is inhabited by thirty different nations.

“The other starts from the country of the Persians, and stretches into the Erythraean sea, containing first Persia, then Assyria, and after Assyria, Arabia. It ends, that is to say, it is considered to end, though it does not really come to a termination, at the Arabian gulf- the gulf whereinto Darius conducted the canal which he made from the Nile. Between Persia and Phoenicia lies a broad and ample tract of country, after which the region I am describing skirts our sea, stretching from Phoenicia along the coast of Palestine-Syria till it comes to Egypt, where it terminates. This entire tract contains but three nations. The whole of Asia west of the country of the Persians is comprised in these two regions.

“Beyond the tract occupied by the Persians, Medes, Saspirians, and Colchians, towards the east and the region of the sunrise, Asia is bounded on the south by the Erythraean sea, and on the north by the Caspian and the river Araxes, which flows towards the rising sun. Till you reach India the country is peopled; but further east it is void of inhabitants, and no one can say what sort of region it is. Such then is the shape, and such the size of Asia.”

Zoroastrian temple

Zoroastrian Religion

Zoroastrianism was the dominant religion of the Persians. It developed around the time of the Jewish Exile or before that. Zoroastrian ideas about good and evil, Heaven and Hell and God and Satan had a lasting impact of Judaism and Christianity. Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The date of Zoroaster's birth is not known and dates accepted by scholars vary from the pre-Exilic through the Exilic periods. According to tradition, he was born in eastern Iran, perhaps near Lake Urmia. Legends concerning his early childhood relate miraculous escapes from enemies who wished to destroy him. The account of his spiritual pilgrimage tells how he was led by Vohu Manah (Good Thought) to an assemblage of spirits and was instructed by Ahura Mazda (also called Ormazd or Hormuzd) in a true or pure religion. His initial efforts to reach his countrymen were unsuccessful, but he eventually converted King Vishtaspa, chief of a small tribal federation. With royal support, the influence of the religion spread and attempts were made to convert neighboring groups by force through a series of holy wars. In one of these wars, Zoroaster died. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

“His teachings centered in a cosmic dualism in which Ahura Mazda, the all-knowing creator and sustainer of the world of good, was pitted against the powers of evil symbolized by Angra Mainyu, the epitome of evil. Here truth struggled with the lie and light battled darkness. Ethical values were attributed to the opposing forces by the prophet, so that right and wrong tended to have black and white characteristics. Man, endowed with free choice, is involved in the cosmic struggle and must choose between the sides. Within this cosmic bipolarity, Zoroaster envisioned history moving toward an ultimate goal. In the final epoch of time, truth and goodness would triumph. Then, in the eschaton, a savior would come to renew all existence and resurrect the dead, uniting the body and soul.

“At death, man's soul approached the "Bridge of Separation" over which the righteous were able to pass to paradise but where the evil were turned back for punishment. At the end of time, after the resurrection, every man would be tested in a flood of molten metal. For the righteous the final test would be as entering a warm bath, but for the evil the fiery test would mean complete extinction. As one possessing free will, the individual could not be judged as a member of a group; nor could he be burdened with the sins of his ancestors. Each man, by personal choice and action, determined his own ultimate fate. The eschatological hopes promised rewards beyond man's wildest dreams or punishment that signified complete extermination.

“When Cyrus seized control of the Median empire during the sixth century and founded his own royal Achaemenid line,12 the house of Vishtaspa, Zoroaster's patron, was terminated. Without royal support Zoroastrianism had to struggle for existence. What impact this religion may have had on Cyrus is not known. The Cyrus cylinder speaks of allegiance to Marduk, and Jewish records indicate that Cyrus spoke of being commissioned by Yahweh to build the Jewish temple (II Chron. 36:22 ff.; Ezra 1:1-4). Possibly Cyrus diplomatically employed the name of whatever god was in popular use in the part of the empire with which he was dealing.13 At present there is no way of knowing what god Cambyses II, son of Cyrus who ruled from 529 to 522, may have worshipped. Not until Darius I, the Great (521-486), the Achaemenid prince who rescued the throne of Persia from a usurper named Gaumata is there any tangible evidence of allegiance to Ahura Mazda and the religion of Zoroaster. On the other hand, the pervasive influence of the great teacher and his followers should not be underestimated, and it is not impossible that some of the expressions of the cosmological motifs in II Isaiah owe something to the teachings of Zoroaster.

Influence of Zoroastrianism

Zorastrian fire pot

Morris Jastrow said: ““With its assertion of a single great power for good as the monarch of the universe, Zoroastrianism approached closely the system of Hebrew monotheism, as unfolded under the inspiration of the Hebrew prophets. There was only one attribute which the god of Zoroastrianism, known as Ahura-Mazda, did not possess. He was all-wise, all-good, but not allpowerful, or rather not yet all-powerful. Opposing the power of light there was the power of darkness and evil which could only after the lapse of aeons be overcome by Ahura-Mazda. But this personification of evil as a god, Ahriman, was merely the Zoro-astrian form of the solution of a problem which has been a stumbling-block to all advanced and spiritualised religions:—the undeniable existence of evil in the world.[Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The chief power of the universe conceived of as beneficent could not also be the cause of evil. It is the problem that underlies the discussions in the Book of Job, the philosophical author of which could not content himself with the conventional view that evil is in all cases a punishment for sins, since suffering so frequently was inflicted on the innocent, while the guilty escaped. The Book of Job leaves the question open, and intimates that it is an insoluble mystery. Zoroastrianism admits that the good cannot be the cause of the evil, but the aim of the good is to overcome evil and eventually it will be able to do so. The dualism of Zoroastrianism is merely a temporary compromise, and, essentially, it is monotheistic.

“Zoroastrianism recognised the reign of inexorable though inscrutable law in the world, and when it began to exercise its influence on Babylonia, the belief in gods acting according to caprice was bound to be seriously affected. So it happened that although the culture of Babylonia and Assyria survived the fall of Nineveh and Babylon, and for many centuries continued to exercise its sway far beyond its natural boundaries, the religion, while formally maintained in the old centres, gradually decayed. The new spiritual force that had entered the country effectually dissolved the long-existing bond between culture and religion. The profound change of spirit brought about through the advent of Zoroastrianism is illustrated by the rise of a genuine science of astronomy, based on the recognition of law in the heavens, in place of astrology, which, in its Babylonian form at least, had a meaning only as long as it was assumed that the gods, personified by the heavenly bodies, stood above law.

“The era was approaching when the sciences one by one would cut loose from the leading strings of religious beliefs and religious doctrines. When, two centuries later, another wave of culture coming from the Occident swept over the entire Orient, it gave a further impetus to the divorce of culture from religion in the Euphrates Valley. Hellenic culture, brought to Babylonia by Alexander the Great and his successors, meant the definite introduction of scientific thought; and thereby a fatal blow was given to what was left of the foundations of the beliefs that had been current in Babylonia for several millenniums. Traces of the worship of some of the old gods of Babylonia are to be found almost up to the threshold of our era, but it was merely the shell of the once dominant religion that was left. The culture of the country had become thoroughly saturated with Greek elements, and what Zoroastrianism had left of the religion that once reflected the culture of the Euphrates Valley was all but obliterated by the introduction of Greek modes of thought and life, and of Greek views of the universe.”

Pasargadae and Susa

Pasargadae Pasargadae (80 miles north Shiraz) is the ancient capital of Persia founded around 550 B.C. by the first Persian Cyrus the Great, where he defeated the Medians in a famous battle. Situated on an isolated 1,800-meter-high plateau, it was built, according to Strabo, as a “memorial to that epic victory” that marked the beginning of the Persian civilization. Pasargadae was the name of the largest Persian tribe.

The ruins are not nearly as interesting as those at Persepolis. They include a massive platform, two palaces, a monumental gate marked by a winged beast with an Egyptian crown and a stone tower known as Zendane-e-Sulaiman (Prison of Solomon). A structure believed to be Cyrus’s tomb consists of a gabled tomb chamber flanked by receding steps. It is sometimes called Solomon’s Mother’s Tomb. Pasargadae means “Persian Camp.”

Susa (50 miles north of Ahwaz) is the site of one of the oldest civilizations in the Middle East. First settled around 5000 B.C., it was occupied by a number of civilizations, including Elamites and Assyrians. Darius the Great built a winter capital for ancient Persian empire. There isn’t much to see other than the the skeletal remains of Persian palaces and a broken bull’s head capitals. A famous headless statue with Egyptian hieroglyphics found here now is in the Archeology Museum in Tehran. Other objects excavated here, including clay inscriptions and pottery, can bee seen in the local museum. Nearby is another ancient city, Shush, which contains an Elamite-style structure which is said to be the tomb of the Old Testament prophet Daniel. Restored several times, it is still a place visited by Jewish, Christian and Muslim pilgrims.

Persians in Ancient Egypt

Egypt was conquered the Persians in 525 B.C. After experiencing a brief period of autonomy it was conquered again by the Persians around. 300 B.C. Egypt remained in Persian hands until they were defeated by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C., at which time Egypt fell under Greek control.

A weak Egypt was no match for Persia at the height of its power. After being conquered by the Persian king Cambyses, Egypt became a backwater province in a large empire. After five Persian rulers, the Egyptian retained control for 10 rulers until the Persian regained control. Among other things the Persians were known for being religiously tolerate and accommodating to the Jews in Egypt.

The Late Period of ancient Egyptians history (715 to 332 B.C.) included the second part of the 25th dynasty, and 26th, 27th, 28th, 29th, 30th and 31st dynasties and one period of Nubia rule and two periods of Persian rule. The 25th dynasty was Nubian. The 27th and 31st dynasties were Persian. After the 27th dynasty the Persians were expelled but returned once again.

Egyptian art from the Persian period includes a headless but still impressive stone statue of Ptahhotep, an Egyptian treasury official, dressed in Persian costume with a Persian bracelet but an Egyptian chest ornament. The sculpture, about one-quarter life size and probably from Memphis, illustrates the accommodating mix of Persian and Egyptian costumes during the period of Egypt's rule by Persian kings.

First Persian Period in Egypt (525 – 404 B.C.)

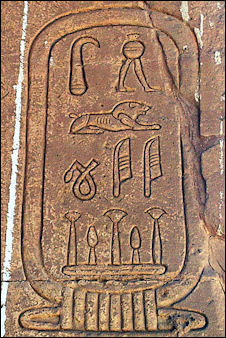

Darius II's Egyptian cartouche The 27th Dynasty and the First Persian Period of Egypt began in 525 B.C. when the Persian king Cambyses II conquered Egypt with a victory at the Battle of Pelusium in the Nile Delta, followed by the capture of Heliopolis and Memphis. The Persians received assistance from Polycrates of Samos, a Greek ally of Egypt, and the Arabs, who provided water for his army to cross the Sinai Desert. After these defeats Egyptian resistance collapsed. In 518 B.C. Darius I visited Egypt, which he listed as a rebel country, perhaps because of the insubordination of its governor Aryandes whom he put to death. Persian rulers of Egypt during the 27th Dynasty who were also the rulers of the Persian Empire were: Cambyses 525-522 B.C.; Darius I 522-486 B.C.; Xerxes 486-465 B.C.; ArtaxerxesI 465-424 B.C.; Darius II 424-405 B.C.; Artaxerxes II 405-359 B.C.; [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com]

David Klotz of New York University wrote:“Scholars divide the Persian Period in Egypt into two separate eras, the First Domination (Dynasty 27,525-402 B.C.) and the brief Second Domination that ended with the arrival of Alexander the Great (Dynasty 31, 343-332 B.C.). To distinguish from other stages of Iranian history, this era is also called Achaemenid, named after the eponymous founder of the dynasty, Achaemenes. In both periods, Egypt was governed by a Persian satrap. [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

James Allen and Marsha Hill of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Egypt's new Persian overlords adopted the traditional title of pharaoh, but unlike the Libyans and Nubians, they ruled as foreigners rather than Egyptians. For the first time in its 2,500-year history as a nation, Egypt was no longer independent. Though recognized as an Egyptian dynasty, Dynasty 27, the Persians ruled through a resident governor, called a satrap, helped by local native chiefs. Persian domination actually benefited Egypt under Darius I (521–486 B.C.), who built temples and public works, reformed the legal system, and strengthened the economy. The military defeat of Persia by the Greeks at Marathon in 490 B.C., however, inspired resistance in Egypt; and for nearly a century thereafter, Persian control was challenged by a series of local Egyptian kings, primarily in the Delta. [Source: James Allen and Marsha Hill, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, BBC and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018