ALEXANDER THE GREAT

Alexander at the Siege of Tyre Alexander the Great conquered Persia in 333 B.C. ...Alexander III of Macedon, Alexander the Great, was perhaps the greatest conqueror of all time. In 334 B.C., at the age of 21, he left the small Greek of Kingdom of Macedonia with 43,000 foot soldiers and 6,000 horsemen to seek revenge against the Persian empire, which had sacked Greece and Macedonia and burnt Athens a century before, and didn’t stop until he conquered much of the known world at that time. [Sources: Richard Covington, Smithsonian magazine, November 2004; Caroline Alexander, National Geographic, March 2000; Helen and Frank Schreider, National Geographic, January 1968. [↔]

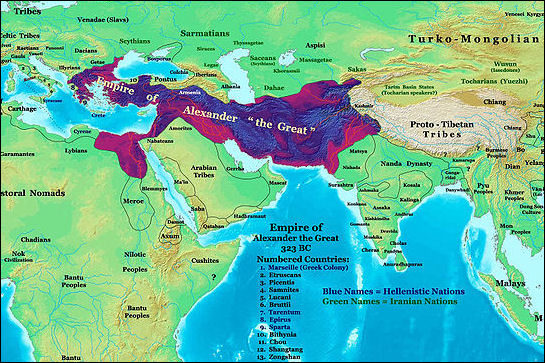

During his 13-year march of conquest Alexander claimed a territory that stretched as far east as India and China, and included present-day Turkey, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Egypt, Libya, Cyprus, Greece, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Pakistan. The same territory would extend from California to Bermuda if it were placed on a map over the United States.

Julius Caesar, Napoleon, Dwight D. Eisenhower, the poet John Dryden and Sigmund Freud were among those who canonized Alexander as a romantic hero. St. Augustine and Dante were among those who vilified him as murderer and plunderer. Historians are equally divided. Some see him as a charismatic leader with a bold vision to unite East and West. Others see him as an ancient Cortez, Hitler or Stalin intent on gobbling up as much territory as he could and if cruel means were need to realize that aim then so be it. Other still see him as man of his times — brutal at times, yes, but within what was acceptable in his era — who opened up the world by bringing the West to the East.

For More on Alexander the Great, See History, Ancient Greeks

Alexander the Great’s March of Conquest

Alexander left Macedonia in 334 B.C. at age of 21 with 43,000 foot soldiers and 6,000 horsemen. He would never return home again. After crossing the Hellesport (now known as the Dardanelles), he marched into Asia Minor and then looped around Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Egypt, and Libya before returning to Asia Minor (this took about four years). Then he and his army zigzagged through Iran and Iraq, where important battles were fought (three years), and continued on through the Hindu Kush mountains in Afghanistan and into Pakistan (three years).

Battle at GaugamelaAlexander went as far north as present-day Tashkent in Uzbekistan and as far east as Jammu and Armistar in India. He followed the Indus River in present-day Pakistan to the Arabian Sea (two years). The most difficult and costly part of the journey was the trip home via the forbidding Baluchistan desert in southern Pakistan and Iran (one year).

Before setting out on his mission of conquest Alexander arrived unannounced at the Oracle of Delphi. He demanded to see the seeress, and when she refused he dragged her into a temple and forced her to tell his prophecy. Plutarch writes: "As if conquered by his violence, she said, 'My son, thou art invincible.'"↔

Why died Alexander undertake his mission of conquest and how did Alexander get his men to go along with him on arduous journey of conquest that had little point. Some say the conquest seems to have been a personal matter for Alexander without further meaning. According to historian Jack Keegan, Alexander was comfortably established as ruler of a half-Barbarian Greek city and seemed to have pillaged Persia "largely for the pleasure of it." Other say Alexander was partly driven by his desire to emulate Achilles and Hercules.

Alexander Battles the Persians at Granicus at Takes Western Asia Minor

Within two years after becoming king Alexander was ready to do battle with Persia, the most powerful kingdom the world had ever known up until that time. The Persian empire extended from present-day Turkey to Pakistan. Alexander's aim was to avenge the Persian invasion of Greece by Xerxes a century and a half before.

After sailing the three-mile distance across the Hellespont Alexander cast his spear into the sand and claimed Asia as his “spear-won prize.” Alexander's first destination was Troy. There he he paid homage to Achilles and Patrokolos at their tomb and offered sacrifices and anointed altars with oil and traded his armor for Achilles' sacred shield at the Temple of Athena.

Alexander's first encounter with the Persians was at Granicus, 100 kilometers northeast of Troy. At that time the Persians controlled the Greek cities along the eastern Aegean. There he faced an advance Persian force of 15,000 cavalry and 16,000 infantry, a third of them Greek mercenaries.

Alexander showed great leadership. The Persian army were spread out over a vast area so Alexander's forces were able to break through the Persian infantry lines and surrounded the mercenaries of the Persian king.

After the Battle of Granicus, the Persians fled inland. In about a year Alexander conquered most of western Asia Minor and the Aegean Greek cities of Ephesus, Halicarnassus, Magnesia, Perge and Side, where he was greeted as a liberator. At Gordium (near Ankara), the ancient court of King Midas, Alexander "solved" the famous puzzle of the Gordium's knot by severing it with blow from his sword. According to legend whoever undid the intricately twisted knot would become the ruler of Asia. ↔ As Alexander's army moved eastward they were just their buying time until they would face off again against the Persians in larger, more pivotal battles.

Crossing of the Granicus

Alexander Battles With the Persians at Issus

At Issus (near Adana, Turkey) Alexander's army of about 50,000 men met a Persian force of perhaps 70,000 men. There is some disagreement over the size the Persian force but most historians agree at least it was larger than Alexander’s.

When Alexander’s army arrived in Issus Alexander ordered them to attack almost immediately even though the soldiers were exhausted from a two-day march. Alexander's cavalry, backed by archers and infantry wielding 5-½ -meter-long pikes outmaneuvered the larger Persian force with well-orchestrated charges. Alexander and his Companions charged into a barrage of arrows and made straight of the chariot of the Persian leader Darius III. Darius freaked and panicked with the Companions bearing down on him and fled, causing the Persian front to collapse and the enemy to lose the battle. Darius fled so quickly he left behind his family, which were captured and held for ransom (although Alexander gave orders that his wife and daughters would not be harmed).

After the battle, Darius offered Alexander one of his daughters in marriage and 10,000 talents in treasures (about a billion dollars in today's money) and all of the territory west of the Euphrates, but Alexander refused. After conquering Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Lebanon, Alexander ventured to Mesopotamia where his forces finished off the Persian army, opening the way for his conquest of Asia.↔

Alexander and the Persians Meet at Guagamela

The key battle in Alexander's campaign took place at Gaugamela (or Arbela, near Mosel in Iraqi Kurdistan, about 420 kilometers north of present-day Baghdad) in 331 B.C. After Alexander rejected Darius's offers of peace, Darius had little choice but to prepare for all out war, which he did from the Persian winter capital of Babylon.

Alexander’s force was outnumbered 5 to 1. The Persian army was comprised of 250,000 soldiers from 24 different subject or mercenary armies including ones made up of Indians, Bactrians, Dahae, Medes, Mardians, Babylonians, Parthians and Arachosians. Darius's force was lead by 40,000 Persian cavalry men clad in chain mail with chariots with scythe blades on their wheels. The Persian leader even had some fighting elephants at his disposal (some say this was the first time Europeans were exposed to elephants). Alexander’s army had 40,000 infantry men and a 7,000-strong cavalry.

Battle of Issus

Uncharacteristically, Alexander exercised caution. He waited four days to attack and overslept on the morning of the battle, which was one of the largest and most decisive battles in antiquity. Plutarch wrote, "When his officer came to him in the early morning, they were astonished him not yet awake."

Fighting at Guagamela

Darius pinned his hopes on his specially-designed chariots which essentially had twirling swords attached to their wheels. To give these vehicles an advantage Darius even went as far as leveling the battlefield and clearing away trees and hills in an area of eight square miles so the chariots could maneuver on the plain where the battle was fought.

Alexander's forces were arranged in a rectangular box while the Persians were drawn out in a long line. Alexander knew he was outflanked anyway so his plan was to protect his flanks and draw the Persian's there so he could attack the middle, where Darius was surrounded by bodyguards.

Alexander ordered one wing of his cavalry to charge Darius’s far left flank and another to aim for the far right, leaving his own infantry vulnerable in the center. When the battle began Alexander's forces moved forward. At the last minute, just as the Persians were set up, Alexander tilted his box, and charged the Persian infantry with a wedge at the right side of the middle. The objective was to draw the Persians to the flanks.

The Persians took the bait. Their cavalry attacked the right flank of Alexander's rectangular box. When the chariots charged Alexander simply ordered his ranks to part with some soldiers given the task of pulling the drivers to the ground when the chariots passed. The rest were picked off with arrows and javelins.

Alexander Defeats the Persians at Guagamela

The Persians then attacked Alexander's left flank. As Darius’s mounted forces were pulled into opposite direction Alexander and his elite forces took advantage of the weakness in the middle and made their move there. The Companions formed a wedge and opened up a hole and Alexander himself went right after Darius in the heart of the Persian army, splitting it in two.

The Persian king lost his nerve after his chariot driver was killed by javelin and again he fled, on horseback. Ironically the Persians had regrouped and were ready to mount a bold counter attack but when they heard their had leader had abandoned them once gain they abandoned their assault and the Macedonians were able to defeat an army five times their size with relative ease.↔

Battle of Gaugamela

Alexander pursued Darius, who was able to get away, but returned to the battlefield to oversee the massacre of the Persian army. When the dust cleared, the Persians lost an estimated 40,000 to 90,000 men while Alexander's army lost only 100 to 500.

A military historian at West Point, Col, Cole Kingseed, told National Geographic: "Alexander's tactic were offensive. He anticipated what the enemy would do, forced the enemy to react to him. Alexander went with the arm of decision — that's one thing we stress, that the commander's place is where the decisive action is."

Looting of the Persian Capital and Darius’s Death

In less than five years Alexander had defeated the mighty Persians. From Gaugamela Alexander marched his troops victoriously into Babylon, with its gardens and walls, which according to legend were 300 foot high and wide enough to accommodate two chariots riding abreast. Along the way he picked up 15,000 Greek reinforcements.

After a month's rest Alexander army moved on to Persepolis, the Persian capital, the home of a grand palace with a golden throne and 100-column hall. There Alexander collected almost 3,000 tons in coins, bullion, gold and silver vessels and jewels (worth perhaps billions in today's dollars). It was one of the richest hordes ever taken. Afterwards Alexander unleashed his soldiers, who formed a drunken mob and burned the palaces of Xerxes to the sound of flutes and songs in revenge against the burning of Athens 150 years before. They also looted art and valuables and killed any male Persians that crossed their path. Great tapestries were placed on the beams of the great palace to set that on fire.

Alexander “accidently” burned down Persepolis in 330 B.C. To carry the treasure of gold, silver and jewels and other goodies back to Greece reportedly required 10,000 mules and 500 camels.

The only loose end that needed to be tied was the capture of Darius. Alexander's army then headed north, moving at an astounding pace of 36 miles a day. At the Caspian gates in the Elburz Mountains (near Tehran) Alexander caught up with Darius. By this time the Persian so feared Alexander that many soldier, according the historian Arrian, "threw themselves over the cliffs."

Darius himself had been abandoned was found shackled and accompanied by a loyal dog in cart pulled by wounded oxen. He reportedly had been stabbed by his own generals and died after a sympathetic Greek soldier gave him some water. Plutarch wrote: "When Alexander came up, he showed his grief and distress at the king's death, and unfastened his own cloak, he threw it over the body." With the conquest of Persia complete, Alexander now was King Persia as well as Macedonia, and controlled western Asia. Modern Iranians blame Alexander for the decline of the Persian empire. Even today they call him "Alexander the Accursed."

Alexander Uses Persian Administrators

Alexander cloaks body of Darius

Alexander showed some skill as an administrator. He tolerated local customs and appointed local administrators. He appointed Persians to many posts and adopted the Persian style of administration even though Persians had long been his sworn enemies. He even wore local clothes of the Persians to earn support of the Persian people, something the soldiers that fought under him took offence to.

Administrative realities sometimes clashed with codes that kept military moral high. Alexander welcomed some Persians into his inner circle and even ordered a royal funeral for his main adversary, Darius III. These moves infuriated some of Alexander’s soldiers and paved the way for a mutiny. Green wrote in his biography “Alexander of Macedon” “the sight of their young king parading in outlandish robes, and in intimate terms with the quacking, effeminate barbarian nobles he had so lately defeated, filled [his troops] with disgust.” Alexander also angered those close to him by ordering the death of Parmenion, a loyal and venerated general who fought under Phillip and Alexander. and Callisthenes, Aristotle's nephew.

When Alexander learned that soldiers were plotting to kill him, he arrested seven of the alleged conspirators, including Philotas , the son of Parmenion. Although the evidence against Philotas was weak he and the others were stoned to death. In a pre-emptive move to stem a revenge attack, Alexander also had the 70-year-old Parmenion stabbed to death. From then on “Alexander never trusted his troops,” Green told Smithsonian magazine, “The feeling was mutual.”

Alexander and Persia

Like other conquerors, some historians said Alexander “went Persian” after his conquest of Persian. After laying waste to Persia’s main cities, he adapted its cultural and administrative practices and took a Persian wife (His beloved Roxana) and ordered thousands of his troops to do the same in a mass wedding.

After Darius' death rumors spread that the campaign was finished and Alexander was ready to head home. To squash these rumors Alexander called a meeting of his generals and told them, according to a 1st century Roman historian Curtius, "with tears in his eyes, complained he was being brought to a halt in the middle of a brilliant career.”

By the time Alexander reached India he was drinking heavily and had adopted modified Persian dress and customs, something that did not endear him to his loyal Macedon troops. He became increasingly paranoid and displayed wild fits of temper at perceived disloyalty. During one drunken party, when Alexander was boasting about his victories, Cleitus, a friend that once saved his life, said that Alexander owed thanks to his father and the Macedonian veterans that had stood by side all for so many years. Alexander was incensed by this remark. He accused Cleitus of being coward to which Cleitus accused him of pandering to the Persians. Enraged all the more, Alexander grabbed a spear and thrust it through his friend’s chest, killing him instantly. Alexander was instantly filled with remorse and pulled the spear from Cleitus’s body and tried to impale himself. Some officers managed to wrestle the spear from him. Alexander shut himself in his tent for days, grieving.

In Hyrcania on the Caspian Sea, Alexander was given a beautiful eunuch named Bagais, who became Alexander's lover. This move was not popular either, nor was Alexander's desire to be treated like a god and requiring his troops to prostrate themselves in front of him and kiss him. Ephippus, a contemporary of Alexander, wrote: "In his honor myrrh and other kinds of incense were consumed in smoke; a religious stillness and silence born of fear held fast all whom were in his presence. For he was intolerable, and murderous, reputed to be melancholy mad."

Alexander's Arduous Journey Home

.jpg)

Wedding of Alexander and Roxane in Persia

The journey back towards Greece proved to be the most arduous part of the journey — more costly than any battle. Instead of returning home the way they came — over the Hindu Kush — Alexander decided to travel south by river with 1,800 ships through what is now Pakistan to the Arabian Sea, a journey that ended up taking months. First they had to fight their way down the Indus River and resistance was met with slaughter on a genocidal scale. In one attack spearheaded by Alexander himself, the great conqueror took an arrow is his lung and to be carried away in a stretcher, but soon after mounted his horse to show his men he wasn't finished yet.↔

Alexander’s army of 87,000 infantry, 18,000 cavalry, 52,000 followers arrived at the Arabian Sea, in a part of the world they were unfamiliar with. Because there were to many men to be carried in boats on the Arabian Sea, Alexander's divided his army, with a small contingent being carried boats and larger contingent journeying overland. A plan was concocted for the army to march overland across the brutal deserts of what is now southern Pakistan and Iran and be supplied by a fleet sailing on Arabian Sea that would meet up with army at various points along the way. That year the monsoon blew the opposite direction and the ships got stuck in Pakistan and were unable to bring supplies to the tens of thousands traveling overland.

Alexander led the largest contingent on a march 1,750 kilometers across the Baluchistan desert, a wasteland more forbidding than the Sahara, and southern Iran. They traveled almost exclusively at night because it was simply too hot during the day. Even at night it travel was difficult as temperatures rarely dropped below 35 degrees C (95 degrees F). Because the supply ships never showed the marchers were forced to subsist on the limited food they brought with them.

The temperatures were blistering and what little water there was largely undrinkable. The trip was so arduous pack animals were butchered and eaten, booty was left behind and more than once the royal stores were broken into. Even then many men died of starvation, thirst and heat.

Alexander suffered along with everyone else. Once he was offered a helmet full of water but he poured it into the sand as a sign that he was willing to share the misery of his troops. Even when there water that could spell trouble too. A large number of his retinue drowned when a flash flood caught them in a canyon.

Alexander’s journey across the deserts of Baluchistan has been compared to Napoleon's retreat from Moscow. The journey took 60 days. About 15,000 of Alexander’s men, or nearly half the fighting force that accompanied him, perished — more than all the men killed in battle. By contrast, the fleets reached the Iranian coast, delayed but almost intact.

Alexander Returns to Persia

In Kirman, Persia Alexander made relations with his men worse when had six of the 20 provincial governors he appointed executed and two more deposed, and then executed 600 men from his own garrisons for raping and pillaging in his absence.

In Susa (Shush, Iran) Alexander took a second wife, Barsine, a daughter of Darius. In a mass wedding — along the lines of those sometimes held by Moonies — 10,000 of Alexander's troops married Persian women and 80 of his officers married daughter of Persian nobles.

Alexander it seemed had become so endeared with Persian culture he had no plans of returning home and instead planned to set up his base of operations in Persia. Some 30,000 noble Persian youths had been taught Greek and methods of Macedonian warfare. As a sort of take off on the Companions they were named the Successors.

By some accounts Alexander’s next destination was Arabia, where he hoped to gain control of area that produced valuable spices. At this time he still “hunted, diced, played ball, joked and banqueted” with his men. In the autumn of 324 B.C., Alexander's boyhood friend and possible lover Hephaestion became ill with unknown disease and died. Alexander was devastated and had Hephaestion's doctor crucified.

Alexander-Empire 323 BC

Hollywood and the Persians

In a number of Hollywood films’such as Oliver Stone’s “Alexander the Great” and “300", the film about the Spartans triumphant last stand at Thermopylae — the Persians are the bad guys, sort of like the Nazis of the classical world. A lot of young Iranians both in and out of Iran resent the way the Persia has been portrayed. One young Iranian rapper told National Geographic, “The Greeks were portrayed as heroic, innocent and civilized. The Persians were shown as ugly savages with method of fighting that was unfair.” The Iranian government has said that negative depictions of the Persians were aimed at “humiliating Iranians” and were “part of a comprehensive U.S. psychological warfare aimed at Iranian culture.”

One film that portrays the Persians in a more favorable light — Disney’s and Jerry Buckheimer’s $150 million , action-packed “Prince of Persia: Sands of Time” — is based on a popular 2003 video game and stars Jake Gyllenhaal, one of the gay cowboys in “Brokeback Mountain”. Gyllenhaal plays the lead character, Datsan, an adopted son of the King of Persia, at time when Persia has just been invaded.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018