ANCIENT IRAN

Tureng Tepe vase

Iran is one of the three oldest Asian civilizations that remains today (not including the Middle East). The other two are China and India. There is evidence of human habitation in the Zagros Mountains in Western Iran as far back as 100,000 years ago. About 15,000 years ago the inland sea of Iran began drying up. The earliest reports of human settlements go back to 10,000 years ago. By 6000 B.C. village farming was practiced among communities living on the Iranian plateau. At the beginning of the third millennium an important civilization appeared at Elam in the southwestern corner of the plateau. Gayomars is the mythical first ruler of Iran. The Kassites are an ancient people who lived on the Qazvin Plain west of present-day Tehran as far back as 2400 B.C. and ruled Mesopotamia (See the Kassites). The Elamites are another very ancient people from Iran that had a strong impact on Mesopotamia.

Iranian tribes entered the plateau which now bears their name in the middle around 2500 B.C. and reached the Zagros Mountains which border Mesopotamia to the east by about 2250 B.C.. Persia contained a number regions of high culture and ancient cities occupied by different ethnic groups that were divided by deserts, steppes and mountains and had no great rivers to link them. Potters in the Iron Age (1400-600 B.C.) in northern and western Iran produced ceramics that had an almost metallic sheen. Their black, red, brown and grey wares that had surfaces like silver, gold and bronze.

K.E. Edulje wrote in Zoroastrian Heritage: “Iran and its immediate surroundings are home to many ancient sites whose origins predate historical records. Some of the regions could very well have been a cradle, if not, the cradle of civilization. The prehistoric finds at archaeological sites are frequently categorized according to Ages. It is a very imprecise and sometime confusing method of categorization since the time at which these ages occurred is different in different regions. Development from the use of stone implements to metal implements did not occur at the same time in different regions. Nor did the transition from stone implements to metal implements take place at one point in time. While it is thought that copper was the first metal used for the making of tools, this author feels that may not apply to Central Asia, where gold was the more readily available metal.[Source: K.E. Edulje, Zoroastrian Heritage ]

See Separate Article: BRONZE AGE, PRE-PERSIAN AND MESOPOTAMIA-ERA IRAN factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran” by D. T. Potts (2017) Amazon.com;

“A History of Iran: Empire of the Mind” by Michael Axworthy (2016) Amazon.com;

“Mountains and Lowlands: Ancient Iran and Mesopotamia” by Paul Collins (2016) Amazon.com;

“Palaeolithic Archaeology in Iran” by Philip E. L. Smith (1986) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to the Neolithic Revolution of the Central Zagros, Iran” by Hojjat Darabi (2015) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Settlement Patterns and Cultures in Susiana, Southwestern Iran: The Analysis of the F.G.L. Gremliza Survey Collection” by Abbas Alizadeh (1992, 2020) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of State Organisations in Prehistoric Highland Fars, Southern Iran: Excavations at Tall-e Bakun” by Abbas Alizadeh (2006) Amazon.com;

“Hasanlu, Volume I: Hajji Firuz Tepe, Iran--The Neolithic Settlement by Mary M. Voigt (1983) Amazon.com;

“The New Chronology of the Bronze Age Settlement of Tepe Hissar, Iran” by Ayşe Gursan-Salzmann and Ayşe Gürsan-Salzmann (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Elamite World” by Javier Álvarez-Mon , Gian Pietro Basello, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Proto-Elamite Settlement and Its Neighbors: Tepe Yaya Period IVC” by Benjamin Mutin and C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky (2014) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Iran: Rise and Fall of the Elamite and Iranian Civilization”

by Amir Reza (2021) Amazon.com;

“Lesser Known People of The Bible: Elam and The Elamites” by Dante Fortson (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Elam CA. 4200–525 BC” by Javier Álvarez-Mon (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State” (Cambridge World Archaeology) by D. T. Potts (2016) Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Gods and Goddesses of the Ancient Near East: Three Thousand Deities of Anatolia, Syria, Israel, Sumer, Babylonia, Assyria, and Elam” by Douglas R. Frayne , Johanna H. Stuckey, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

Neolithic Sites in Iran

Many of the oldest sites in Iran are tappehs (ancient burial mounds). Among these are Tappeh Sialk, near Kashan, where 6,000-year-old pottery has been found; Tappeh Hesar, near Damghan, and Tappeh Turnag, near Astar Abad, both of which have been dated to be 7,500 years old; and Tappeh Median, which revealed silver bars, cut silver and silver ring money dated to 760 B.C. Among the other important pre-Persian sites are Shahr-e-Sukhteh, a 5000-year-old town with evidence of extensive trade; Tappeh Yahya, south of Kerman, a 5000-year-old sites with examples of early writing and trade between East and West; and Tall-e-Malyan, near Persepolis, believed to be the lost Elamite city of Anshan.

Near the Caspian Sea and in the upper reaches of the Tigris River, Paleolithic, Mesolithic and pre-pottery Neolithic materials have been recovered, largely from caves. At Mesolithic sites below Lake Urmia (Karim Shahir, Zawi Chemi, Shanidar), circular dwelling foundations of stone with hearths, storage bins, grinding stones and other implements, together with bones of sheep, cattle and dogs, indicate the beginnings of settled culture. These sites may have been occupied only seasonally.

K.E. Edulje wrote in Zoroastrian Heritage: ““We find various prehistoric sites in Iran-Shahr, the greater Iran region called a tepe (also spelt depe, tape, tappeh, tappa, teppeh or tappe). The word means a mound or small (artificial) hill. The mound or hill is formed by soil covering an ancient settlement, or soil formed from mud-brick structures that later human occupation have compressed over time into artificial hills. In treeless areas, the presence of a tepe suddenly rising from an otherwise flat terrain, may indicate ancient settlement buried under the soil. The tepe sometimes consists of the different layers of construction, each with a different dating. The lower layers are therefore normally the older layers.” [Source: K.E. Edulje, Zoroastrian Heritage ]

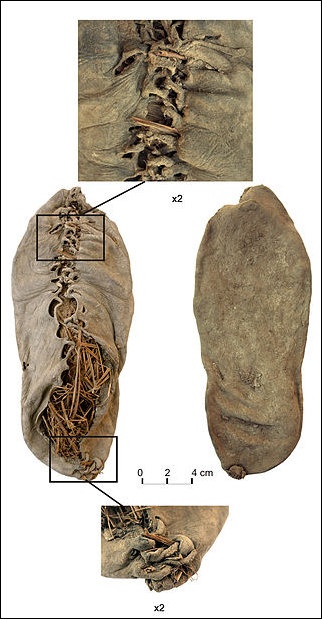

Bronze Age and the World's First Known Shoes

world's oldest shoes from near Iran

The oldest known leather shoe — a 5,500-year-old leather moccasin — was found in was found in a cave near the village of Areni, Armenia. The 24.5-centimeter-long, 7.6- to-10-centimeter-wide covered piece of footwear was made of an old piece of leather. It had laces and was sawed to fit around the wearer's foot. Announced in June 2010, the discovery was made near the Armenian-Turkish-Iranian borders by a team from University College Cro in Vayotz Dzor province.

During the forth millennium in present-day Turkey, Iran and Thailand man learned that these metals could be melted and fashioned into a metal — bronze — that was stronger than copper, which had limited use in warfare because copper armor was easily penetrated and copper blades dulled quickly. Bronze shared these limitations to a lesser degree, a problem that was rectified until the utilization of iron which is stronger and keeps a sharp edge better than bronze, but has a much higher melting point. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The Bronze Age lasted from about 4,000 B.C. to 1,200 B.C. During this period everything from weapons to agricultural tools to hairpins was made with bronze (a copper-tin alloy). Weapons and tools made from bronze replaced crude implements of stone, wood, bone, and copper. Bronze knives are considerable sharper than copper ones. Bronze is much stronger than copper. It is credited with making war as we know it today possible. Bronze sword, bronze shield and bronze armored chariots gave those who had it a military advantage over those who didn't have it.

Copper tools had been around for long before bronze ones. Therefore the key ingredient that made the Bronze Age and innovation possible was tin. Copper was readily available over a large area. Much of it came from Cyprus. Tin was harder to find. It came mainly from mountains in Turkey and in Cornwall. Because tin was scarce and found in only localized regions, trade routes on which it was transported were set up. Tin itself became a highly profitable trade item. Taxes were placed on tin. Tolls were put in place on the trade routes.

First Domesticated Goats from Iran?

Goats first appeared around 5 million years ago. The lived primarily in mountainous habitats and spread out an inhabited other region. Modern goats can eat food that other animals can't partly because the originated from harsh, rocky mountain environments.

Goats rank with pigs and dogs as one of the earliest domesticated animals and rank with sheep as one of the first animals to be kept for milk. Modern goats are believed to have been domesticated from Markor goats or Bezoar goats from Western Asia about 9,000 to 10,000 years ago. Wild Markor goats can still be found in the dry mountains of Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan.

Bezoar

Bones from what appear to be domesticated goats have been found in Iraq and Iran dated to from 8,500 B.C. . Ganj Dareh, a 10,000-year-old site in the Fertile Crescent, yielded a number bones of many small goats. Archeologist believe that these goats were domesticated rather than wild based on the practice of hunter societies to kill the largest animals available while herders kill smaller animals and keep the large ones to breed.

People who lived in Iran 9,000 years ago kept a few males to breed and killed off the rest of the male goats at age two, about the time they reached sexual maturity, while females were allowed to grow older because they supplied milk and produced babies, a pattern that continues today.

The Mesopotamians wrote poems about goats, depicted them in golden sculptures, worshiped them as gods and made the goat-god Capricorn into a Zodiac sign. Goats were taken all over the world to trade as sources of meat, wool and milk. Goats are mentioned in the Bible as well as in Buddhist, Confucian and Zoroastrian texts. In Greek myths, the gods were nursed on goats milk.

Raphael Pumpelly (1837-1923), Early Archaeologist of Iran

K.E. Edulje wrote in Zoroastrian Heritage: “More than a century ago an unlikely geologist from New York put forth a proposition that "the fundamentals of civilization - organized village life, agriculture, the domestication of animals, weaving," (including mining and metal work) "originated in the oases of Central Asia long before the time of Babylon." [Source: K.E. Edulje, Zoroastrian Heritage ]

“Raphael Pumpelly arrived at this conclusion after visiting Central Asia as a geologist and observing the ruins of cities on the ancient shorelines of huge, dried inland seas. By studying the geology of the area, he became one of the first individuals to investigate how environmental conditions could influence human settlement and culture. Pumpelly speculated that a large inland sea in central Asia might have once supported a sizeable population. He knew from his travels and study that the climate in Central Asia had become drier and drier since the time of the last ice age. As the sea began to shrink, it could have forced these people to move west, bringing civilization to westward and to the rest of the world. He hypothesized that the ruins of cities he saw were evidence of a great ancient civilization that existed when Central Asia was more wet and fertile than it is now.

“Such assertions that civilization as we know it originated in Central Asia sounded radical at a time when the names of Egypt and Babylon, regions connected to the Bible, were considered to be the cradle of civilization. But Pumpelly was persistent. Forty years after his first trip to Central Asia, he convinced the newly established Andrew Carnegie Foundation to fund an expedition. Since the Russians controlled Central Asia, he charmed the authorities in Saint Petersburg into granting him permission for an archaeological excavation. The latter even provided Pumpelly with a private railcar. At the age of 65, Pumpelly was given the opportunity to prove his theory and he wasted no time in starting his work.”

Raphael Pumpelly

“Pumpelly carefully excavated the north mound” of his first excavation site in Central Asia at Anau “by digging a series of eight terraces and shafts. He carefully labelled the position of each item he uncovered. He employed fine-scale archaeology methods (methods that are now utilized by modern archaeologists) by using sieves to capture seeds and tiny bones. Then he had specialists, such as botanists and anatomists, analyze his finds. These pioneering methods would only gradually be used by archaeologists over the next century. In the absence of modern methods like radiocarbon dating, Pumpelly used his training as a geologist, keeping careful stratigraphic records to date sites. His findings would come close to matching data collected years later using modern technology and at considerably greater cost.

“Pumpelly's early interest in how humans respond to environmental change is still a keynote feature of archaeology. The kurgan digs unearthed pottery, objects of stone and metal, hearths and cooking utensils - even the remains of skeletons of children found near hearths. He discovered evidence of domesticated animals and cultivated wheat - evidence of the civilization the sought.

“Later Pumpelly was to write in his memoirs, "A close watch was kept to save every object, large and small,... and to note its relation to its surroundings. I insisted that every shovelful contained a story if it could be interpreted." Indeed, every shovelful, even grain, and every shard had a story to tell.

First Wine in Iran

China and Iran both claim to have produced the world's first known wine. An archaeological site called Hajii Firuz (Firuz Tepe) in the Zagros mountains in Iran with mud brick-buildings dating to 5400-5000 B.C. yielded jars with traces of tartaric acid (a chemical indicator of grapes), calcium tartrate and terebinth resin, which are left behind by dried wine. There were also remains of stoppers which could have been placed in the jars to prevent wine from tuning into vinegar. Based on the colors of the residues, the Neolithic people that lived there enjoyed both red and white wine. The site was identified by a team lead by Patrick McGovern, an ancient-wine expert and a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, in 1996.

Ceramic remains unearthed at Godin Tepe in the Zagros Mountains suggest that wine was produced there about 3,500 B.C., pushing back the earliest documented evidence of wine making by about 500 years. The discovery was made by a graduate student at the Royal Ontario Museum who noticed a stain on a vessel she was assembling. When the stain was analyzed it revealed tartaric acid, a substance found abundantly in grapes. If the stain was indeed made from wine it shows that wine-making and writing evolved about the same time. [National Geographic Geographica, March 1992].

The first domesticated grapevines are believed to have been developed in the northern Near East, perhaps in Armenia or perhaps in the Zagros mountains of Iran, where wild grapes still grow today and pollen cores show they grew in Neolithic times. By 3000 B.C. domesticated grapes had been transplanted to the Jordan Valley, which became a major exporter of wine. It produced large amounts of wine that was traded to Egypt and elsewhere. An Egyptian King named Scorpion who was buried in 3150 B.C. with 700 jars of imported wine.

Hajji Firuz and the World's Oldest Wine-Making

Zagros mountains

K.E. Edulje wrote in Zoroastrian Heritage: “Persians were known for their wine-making, and the site now called Hajji Firuz, just west of Hasanlu, is noted for the discovery of a jar containing the earliest known residue of wine in the world. The residue contained resin from the Terebinth tree that grew wild in the region, and was possibly used as a preservative indicating that the wine was deliberately made and was not result of the grape juice fermenting unintentionally. Terebinth resin was widely used as a preservative in ancient wine because it killed certain bacteria. Pine resin is currently used in Greek Retsina wine. [Source: K.E. Edulje, Zoroastrian Heritage ]

“The jar with the wine residue, had a volume of about 9 litres (2.5 gallons), and was found together with five similar jars embedded in the earthen floor along one kitchen wall of a Neolithic mud brick building, dated to c. 5400-5000 B.C.. Clay stoppers about the same size as the jars' mouths were located close by, suggesting that they could have been used keep out the air and prevent the wine

“The building in which the jars were found, consisted of a large room that may have doubled as a bedroom, a kitchen, and two storage rooms. The room thought to be a kitchen had a fireplace and numerous pottery vessels probably used to prepare and cook foods. It is unclear if the name of the site has any connection with the trickster who is supposed to make an appearance at Nowruz or New Year's day.

“At Godin Tepe, a 3500-3000 B.C. settlement six hundred km (400 miles) south along the Zagros mountains, additional jars containing wine residues have been found.

Also see Hajji Firuz Tepe, Iran by Mary M. Voigt, Richard H. Meadow

Anau

K.E. Edulje wrote in Zoroastrian Heritage: “Anau is a site eight kilometres southeast of Turkmenistan's Ashgabat modern-day capital, Ashgabat, and its name is derived from Abi-Nau, meaning new water. In earlier times, its name was Gathar.In the delta around Anau, there are three mounds or kurgans (also called tepe or depe), each containing ruins from a different period. The north mound has layers from the 5th millennium B.C. to the 3rd millennium B.C., at which time in history the river Keltechinar appears to have changed course causing a population shift to the south mound that has layers from the mid-3rd millennium B.C. to the 1st millennium B.C. (the Bronze Age). The east mound has the most recent (medieval to classical period) ruins. [Source: K.E. Edulje, Zoroastrian Heritage ]

In 1886, a Russian general A. V. Komarov who mistakenly thought the mound was an ancient burial site with treasure worth plundering, had his army brigade cut through the north mound, bisecting the mound. When Pumpelly visited the site in 1903, his training as a geologist enabled him to see twenty stratified occupational layers in this trench. Pumpelly returned to the site in 1904 to start excavations along the Russian trench using sophisticated methods - methods in stark contrast with the plundering dig of the Russians.

“The story of Anau that emerged was one of a planned walled city that was home to a community that farmed wheat, manufactured artefacts and traded with its neighbours. His work had barely begun, when in 1904 a plague of locusts "filled the trenches faster than they could be shovelled," and plunged the area into famine, forcing him to abandon the dig, never to return. This phenomenon should not go unnoticed since it might provide clues on the reasons why some settlements appear to have been abandoned in ancient times.

“Traveling eastward, he noted the mounds dotting the foothills of the Kopet-Dag, indicating that Anau was not an isolated town, but part of a community of settlements that stretched for a few hundred kilometres, settlements that based themselves on the waters and fertile soil brought down from the mountains. Leaving the mountains, Pumpelly followed the river Murgab north towards the Kara Kum desert. Extreme heat stopped him from exploring the upper reaches of the Murgab delta. Had he done so, he could surely have arrived on the unmistakeable depe mounds of Gonur. That discovery would have to wait for another seventy years and the efforts of a Russian archaeologist of Greek descent, Viktor Sarianidi.

Tepe Hissar

K.E. Edulje wrote in Zoroastrian Heritage: “Tepe Hissar, an archaeological site of largest known urban settlement in the northeast corner of present-day Iran, flourished from 4,500 to 1,900 B.C. (Metal Age). It is located ninety kilometres southeast of the Caspian Sea, near the modern city of Damghan, along the south slopes of the Alburz mountains, and south of Turkmenistan. Hissar was strategically and centrally located on the east-west trade route. Amongst the artefacts found at the site, were those made from lapis lazuli turquoise from Badakshan in the east. [Source: K.E. Edulje, Zoroastrian Heritage ]

According to The Shelby White-Leon Levy Program for Archaeological Publications, Harvard University: "Its strategic location along the major East-West trade route, between southern Mesopotamia, Iranian plateau and Central Asia, further heightens its presumed economic and political role in the region. The importation of lapis and turquoise implies connections with the east, and at the same time links with the west have been documented by blank clay tablets reminiscent of Proto-Elamite tablets, and a cylinder seal. Its importance, therefore, as a cornerstone of chronology, cannot be overemphasized."

“According to the British Museum in their description of a Bronze Age, c. 2400-2000 B.C., Lapis lazuli stamp seal from the Ancient Near East"... Behind the man are a long-horned goat above a zebu. This last animal is related in style to similar creatures depicted on seals from the Indus Valley civilization, which was thriving at this time. There were close connections between the Indus Valley civilization and eastern Iran. One of the prized materials that was traded across the region was lapis lazuli, the blue stone from which this seal is made."

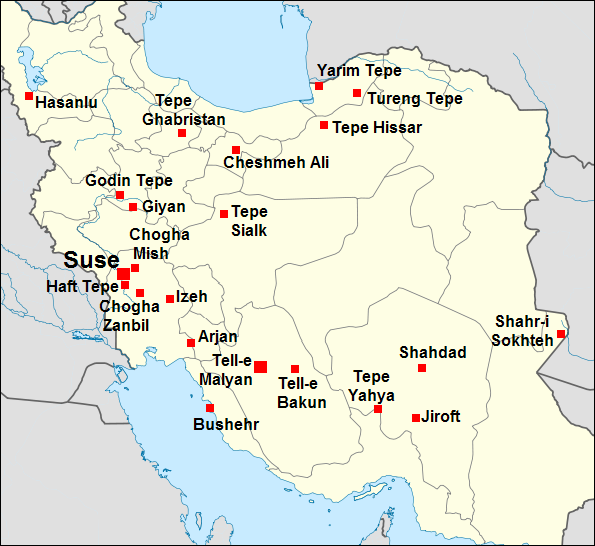

ancient sites in Iran

Tureng Tepe

K.E. Edulje wrote in Zoroastrian Heritage: “An archaeological site known locally as Tureng Tape (also spelt Torang/Turang/Turanga Depe/Tepe/Tappeh/Tapeh/Tappe/Tappa), the hill of the pheasants, is located 22 km (18 as the crow flies) northeast of Gorgan near Kuran Tappeh. Excavations in 1932 revealed five distinct layers, the earliest dating back to the sixth millennium B.C. (the Chalcolithic or Copper Age) and the latest to between 630-1050 CE. [Source: K.E. Edulje, Zoroastrian Heritage ]

“During the Bronze Age (second half of the third millennium and the early second millennium B.C.) Tureng Tepe was one of the largest centres of north-eastern Iran yet discovered. Gold, bronze, and stone objects, dating to this time, called the Astarabad Treasure, were found at the site. The culture of Tureng Tepe during the city's zenith closely parallels that of Tepe Hissar. Occupied until the medieval ages, Torang was also a caravanserai, a caravan station, along the Aryan trade roads until it was destroyed during The Mongol period (1220-1380).

“The appearance of a plain grey pottery dated to the third millennium B.C. has led to speculation that the change marks the entry of Aryan tribes into the region. This reasoning is highly speculative. Nevertheless, the site is evidence of an extremely old civilization that was advanced for its times, residing in the area. The tepe forms a natural link with the tepes along the northern slopes of the Kopet Dag and shares interesting connections with sites in Balkh and in the eastern Iranian plateau.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, the BBC and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024