RULERS OF THE ACHAEMENID PERSIAN EMPIRE (550–330 B.C.)

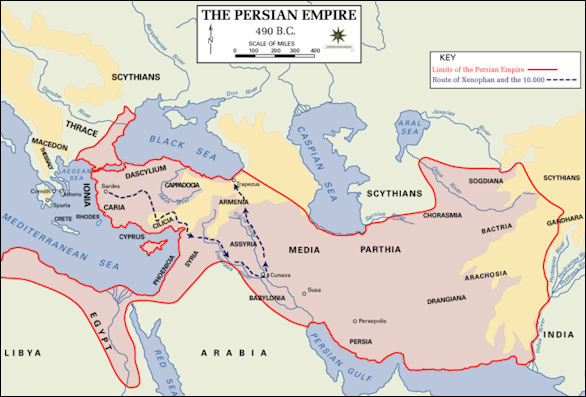

The Achaemenid Persian empire was the largest that the ancient world had seen, extending from Anatolia and Egypt across western Asia to northern India and Central Asia. The Neo-Babylonians (Chaldeans) gave up Babylon without a fight in 539 B.C. to the Persian king Cyrus. By 546 B.C., Cyrus had defeated Croesus, the Lydian king of fabled wealth, and had secured control of the Aegean coast of Asia Minor, Armenia, and the Greek colonies along the Levant . Moving east, he took Parthia (land of the Arsacids, not to be confused with Parsa, which was to the southwest), Chorasmis, and Bactria. He besieged and captured Babylon in 539 and released the Jews who had been held captive there, thus earning his immortalization in the Book of Isaiah. When he died in 529, Cyrus's kingdom extended as far east as the Hindu Kush in present-day Afghanistan. [Source: Library of Congress, December 1987 *]

His successors were less successful. Cyrus's unstable son, Cambyses II, conquered Egypt but later committed suicide during a revolt led by a priest, Gaumata, who usurped the throne until overthrown in 522 by a member of a lateral branch of the Achaemenid family, Darius I (also known as Darayarahush or Darius the Great). Darius attacked the Greek mainland, which had supported rebellious Greek colonies under his aegis, but as a result of his defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 was forced to retract the limits of the empire to Asia Minor. *

The Achaemenids thereafter consolidated areas firmly under their control. It was Cyrus and Darius who, by sound and farsighted administrative planning, brilliant military maneuvering, and a humanistic worldview, established the greatness of the Achaemenids and in less than thirty years raised them from an obscure tribe to a world power.*

The quality of the Achaemenids as rulers began to disintegrate, however, after the death of Darius in 486. His son and successor, Xerxes, was chiefly occupied with suppressing revolts in Egypt and Babylonia. He also attempted to conquer the Greek Peloponnesus, but encouraged by a victory at Thermopylae, he overextended his forces and suffered overwhelming defeats at Salamis and Plataea. By the time his successor, Artaxerxes I, died in 424, the imperial court was beset by factionalism among the lateral family branches, a condition that persisted until the death in 330 of the last of the Achaemenids, Darius III, at the hands of his own subjects.*

Achaemenid Persian dynasty

Cyrus II the Great: 559–530 B.C.

Cambyses II: 530–522 B.C.

Darius I: 521–486 B.C.

Xerxes: 486–465 B.C.

Artaxerxes I: 465–424 B.C.

Darius II: 423–405 B.C.

Artaxerxes II: 405–359 B.C.

Artaxerxes III: 358–338 B.C.

Artaxerxes IV: 338–336 B.C.

Darius III: 336–330 B.C. [Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Books: Briant, Pierre From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2002. Wiesehöfer, Josef Ancient Persia: From 550 B.C. to 650 AD. London: I.B. Tauris, 1996.

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus the Great is generally regarded as the first Persian king, or Shah. He began as a ruler of a small kingdom. Over a ten year period between 559 and 549 B.C. he united the various Persian tribes and conquered the Medes to create the Persian Empire. Said to have been of humble origins, he was regarded as both a great warrior and a just statesman, who treated his subjects and enemies with compassion.

According to a semi-mythical story retold by Herodotus Cyrus had an Oedipus-like childhood. He was condemned to exposure as a baby but returned as a young man to seek revenge against all those who wronged him. Cyrus the Great conquered Babylonia, defeating the declining Neo-Babylonians with relative ease, released the Jews from captivity, and slowly expanded westward across Asia Minor. The Persian and Medes warriors under his command were skilled charioteers and fighters. They carried out light, hide-covered shields and fought with bows and arrows. They relied on speed, quick attacks and luring armed opponents within range of their arrow attacks.

Cyrus the Great won Assyria by defeating the Medes. He conquered Lydia, ruled by King Croesus, in 546 B.C. This gave him possession of much of Asia Minor. Babylon was ruled by the Chaldean Empire, who had enslaved the Jews. The Chaldeans gave up Babylon without a fight in 539 B.C. Cyrus thus claimed the ancient city and acquired Palestine. He allowed the Jews to return to their homeland and rebuild their temple. With his empire in the Middle East secure, Cyrus the Great turned his attention to the east. He extended the border of his empire into India. Among the early kingdoms to fall was exotic Massagetae, which did not have much experience with wine and were easily subdued after they were all gotten drunk. Over the next 60 years, Cyrus and his successors Cambyses (ruled 530-522 B.C.) and Darius I swept north, east and west to expand the Persian Empire. Cambyses was Cyrus’s son. He captured weak Egypt in short campaign and was regarded a cruel tyrant. See Egyptians

See Separate Article: CYRUS THE GREAT (ruled 559-549 B.C.) factsanddetails.com

Cambyses II: the Persian Conqueror of Egypt

Cambyses II, son of Cyrus and Cassadane, was born in 558 B.C. and came to the throne during a major rebellion. He moved swiftly to put down the uprisings only to find that his brother, Smerdis, was a primary instigator behind it. In Persian, it was a tradition for the younger sibling to attempt a coup and usurp the throne of the elder brother. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato]

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: After the death of Cyrus, Cambyses inherited his throne. He was the son of Cyrus and of Cassandane, the daughter of Pharnaspes, for whom Cyrus mourned deeply when she died before him, and had all his subjects mourn also. Cambyses was the son of this woman and of Cyrus. He considered the Ionians and Aeolians slaves inherited from his father, and prepared an expedition against Egypt, taking with him some of these Greek subjects besides others whom he ruled. . [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Cambyses II once reportedly remarked to his mother that when he became a man, he would turn all of Egypt upside down. After eliminating his brother, he was now free to organize a long-anticipated expedition to bring the riches of Egypt into the Hittite Empire. And the time was ripe after Egypt weakened its military with two disastrous campaigns into Syria and Babylon by the unpopular pharaoh, Hophra. There was also a power struggle between Hophra’s regime and the supporters of Amassis, a popular military commander. This struggle ended in Hophra’s untimely demise. Amassis knew the danger that Cambyses II posed and looked to the Greeks for help, which proved fruitless. In fact, Polycrates of Samos actually offered his aid to the Hittites. +\

See Separate Article: PERSIAN CONQUEST AND EARLY RULE OF ANCIENT EGYPT: CAMBYSES II AND UDJAHORRESNET africame.factsanddetails.com

Darius I

David Klotz of New York University wrote: “Darius assumed the throne, reorganized the Empire, and spent much of his time stamping out regional uprisings, including one in Egypt. Recently discovered temple inscriptions from Amheida (Dakhla Oasis) reveal the extent of his rebellion. Furthermore, Aryandes, the first Egyptian satrap, may have tried to break away from the Empire; Darius had him executed for introducing his own coinage; a different tradition maintains that Egyptians revolted against Aryandes and his oppressive policies.” [Source: David Klotz, New York University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2015, escholarship.org ]

Darius I (ruled 522-486) made Persia into a great empire, raised it to the pinnacle of its wealth and glory and added vast lands to the east, west and north. He was a nephew of Cyrus the Great and a cousin of Cambyses. He died in 486 B.C. after the Persians embarrassing defeat at the Battle of Marathon to the Greeks, while he was preparing to retaliate. Darius married at least 5 women and had 12 children, including Xerxes, his successor. He ruled for thirty-six years.

Darius I, is said to have become king in a very unusual way. His predecessor Cambyses left Egypt in 522 B.C. and died en route to Persia. His brother, Bardiya/Smerdis — or the impostor Gaumata — succeeded him briefly until Darius led a coup and assassinated him in the same year. Darius was one of seven men who were to find and kill an imposter named Smerdis. Upon the death and beheading of Smerdis and several others who got in the way of the seven men, a massacre broke out when the people saw the heads of the traitors. The remaining men decided that after they were mounted on their horse, whichever horse neighed first at sunrise should have the kingdom. Oebares, groom of Darius, managed to get Darius’ horse to neigh when everyone was mounted at sunrise one day making Darius ruler of the New Kingdom. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato]

Darius established an empire that extended from the Mediterranean to the Indus River. His greatest contribution was perfecting a system of government that could rule such a large empire and bring wealth and military support from all corners of the empire to the central government. He built imperial highways and oversaw the construction of a canal between the Nile and the Red Sea.

See Separate Article: DARIUS I (ruled 522-486 B.C.) factsanddetails.com

Xerxes

Xerxes Xerxes (ruled 486-465 B.C.) was the son of Darius. He was regarded as weak and tyrannical. He spent the early years of his reign putting down rebellions in Egypt and Babylon and preparing to launch another attack on Greece with a huge army that he assumed would easily overwhelm the Greeks.

Herodotus characterizes Xerxes as man a layers of complexity. Yes he could be cruel and arrogant. But he could also be childishly petulant and become tear-eyed with sentimentality. In one episode, recounted by Herodotus, Xerxes looked over the mighty force he created to attack Greece and then broke down, telling his uncle Artabanus, who warned him not to attack Greece, “by pity as I considered the brevity of human life.”

In October, a mummy was found with a golden crown and a cuneiform plaque identifying it as the daughter of King Xerxes was found in a house in the western Pakistani city of Quetta. The international press described it as a major archeological find. Later it was revealed the mummy was a fake. The woman inside was a middle-age woman who died of a broken neck in 1996.

See Separate Article: XERXES (ruled 486-465 B.C.) factsanddetails.com

After Xerxes

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Xerxes was assassinated and was succeeded by one of his sons, who took the name Artaxerxes I (r. 465–424 B.C). During his reign, revolts in Egypt were crushed and garrisons established in the Levant. The empire remained largely intact under Darius II (r. 423–405 B.C), but Egypt claimed independence during the reign of Artaxerxes II (r. 405–359 B.C). Although Artaxerxes II had the longest reign of all the Persian kings, we know very little about him. Writing in the early second century A.D., Plutarch describes him as a sympathetic ruler and courageous warrior. With his successor, Artaxerxes III (r. 358–338 B.C), Egypt was reconquered, but the king was assassinated and his son was crowned as Artaxerxes IV (r. 338–336 B.C.). He too was murdered and replaced by Darius III (r. 336–330 B.C.), a second cousin, who faced the armies of Alexander III of Macedon ("the Great"). Ultimately Darius III was murdered by one of his own generals and Alexander claimed the Persian empire. However, the fact that Alexander had to fight every inch of the way, taking every province by force, demonstrates the extraordinary solidarity of the Persian empire and that, despite the repeated court intrigues, it was certainly not in a state of decay. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Xerxes' Tomb

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: ““In 460, Egypt, supported by Greece, revolted against Artaxerxes I Longimanus (465-424), son of and successor to Xerxes, and it was not until 455 that Egypt again came under Persian rule. Darius II, son of Artaxerxes I by a Babylonian concubine, came to power following a civil war marked by numerous assassinations, and he reigned during a tumultuous time in Persian history. Satraps rebelled and weakened the empire. Fortunately for the Persians, the Greeks were embroiled in their own Peloponnesian war and were far too busy to take advantage of Persia's weakness. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“Artaxerxes II Mnemon (404-359), the next monarch, struggled through civil war, intrigues, assassinations, and a revolt by which Egypt gained her long-sought independence. When Artaxerxes III (358-338) assumed the throne, his able but ruthless approach brought the loss of provinces by rebellion to a halt and made possible the repossession of some areas previously lost. When provinces along the Mediterranean revolted, the Persian army, greatly strengthened by Greek mercenaries, attacked and destroyed a number of coastal towns, including Sidon, and opened the way for an attack on Egypt. About this same time, Philip of Macedon was uniting Greece, and now Greek armies, strengthened by Macedonian forces, were poised for world conquest.

“Artaxerxes III was murdered by a certain Bagoas, a eunuch, who exterminated most of the Achaemenid line before passing the kingship to Darius III Codommanus (335-331) because, as an imperfect man, Bagoas could not rule.

After the Persians were defeated by Alexander the Great, Judea became a province of the Greek-ruled Seleucid (Syrian) kingdom.

Darius III— Alexander’s Flawed Persian Rival

Darius III Codommanus (335-331 B.C.) reconquered Egypt but was unable to withstand the tremendous military power of the new Greek-Macedonian forces led by Alexander the Great. Under him, the Hellenization of the Near East, already well under way, was to be greatly accelerated.

The Roman historian Arrian wrote: ““This king was a man pre-eminently effeminate and lacking in self-reliance in military enterprises; but as to civil matters he never exhibited any disposition to indulge in arbitrary conduct; nor indeed was it in his power to exhibit it. For it happened that he was involved in a war with the Macedonians and Greeks at the very time he succeeded to the regal power; and consequently it was no longer possible for him to act the tyrant towards his subjects, even if he had been so inclined, standing as he did in greater danger than they. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“As long as he lived, one misfortune after another was accumulated upon him; nor did he experience any cessation of calamity from the time when he first succeeded to the rule. At the beginning of his reign the cavalry defeat was sustained by his viceroys at the Granicus, and forthwith Ionia Aeolis, both the Phrygias, Lydia, and all Caria except Halicarnassus were occupied by his foe; soon after, Halicarnassus also was captured, as well as all the littoral as far as Cilicia. Then came his own discomfiture at Issus, where he saw his mother, wife, and children taken prisoners.

“Upon this Phoenicia and the whole of Egypt were lost; and then at Arbela he himself fled disgracefully among the first, and lost a very vast army composed of all the nations of his empire. After this, wandering as an exile from his own dominions, he died after being betrayed by his personal attendants to the worst treatment possible, being at the same time king and a prisoner ignominiously led in chains; and at last he perished through a conspiracy formed of those most intimately acquainted with him. Such were the misfortunes that befell Darius in his lifetime; but after his death he received a royal burial; his children received from Alexander a princely rearing and education, just as if their father had still been king; and Alexander himself became his son-in-law. When he died he was about fifty years of age.”

See Separate Article: ALEXANDER THE GREAT BEGINS HIS CAMPAIGN AND BATTLES THE PERSIANS AT GRANICUS europe.factsanddetails.com ; ALEXANDER THE GREAT BATTLES THE PERSIANS AT ISSUS europe.factsanddetails.com ; ALEXANDER THE GREAT DEFEATS THE PERSIANS AT GAUGAMELA europe.factsanddetails.com ; ALEXANDER THE GREAT CLAIMS PERSIA AND BABYLON AND CHASES AFTER DARIUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Darius III

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, BBC and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024