MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT ROME

Marriage was regarded as a duty and a means of preserving families. Most marriage were arranged by fathers and set up as alliances between families with producing "legitimate" children as the primary goal. Roman men held marriage in low regard and when they married produced few children. Girls were often forced to marry when they were fourteen. It was not uncommon for a man to marry and divorce several time for his family to work their way up the social ladder. This contempt for marriage kept the population of Rome relatively low while the population of non-Romans and Christians grew.

The marriage customs comprised, first, the ceremony of betrothal (sponsalia), which included the formal consent of the bride’s father, and an announcement in the form of a festival or the presentation of the betrothal ring; secondly, the marriage ceremony, which might be either a religious ceremony, in which a consecrated cake was eaten in the presence of the priest (confarreatio), or a secular ceremony, in which the. father gave away his daughter by the forms of a legal sale (coemptio). In the time of the empire it was customary for persons to be married without these ceremonies, by their simple consent, During this time, also, divorces became common and the general morals of society became corrupt. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)\~]

Marriages were sometimes conducted with a great deal of pomp and ceremony but they were not recognized by the state or a religious body. The only legal matter was that children be "legitimate" to inherit property. The legal-minded Romans developed sophisticated marriage certificates that spelled out the terms of the dowry and how property would be divide in case of divorce or death. The oldest known marriage certificate was a Jewish one found in Egypt and dated to the forth century B.C. It was a contract for an exchange of six cows for a 14-year-old girl.

Most people married young: Girls were regarded as ready when they turned 12 and boys when they were 14. Men who were 25 and women who were 20 and still single were penalized. Brides were expected to be virgins. Grooms were expected to have already had some experience with prostitute or slaves. Some children were betrothed at infancy.

Jana Louise Smit wrote for Listverse: “ Roman marriages were quick and easy and most didn’t flower from romance but from two agreements. The first would be between the couple’s families, who eyeballed each other to see if the proposed spouse’s wealth and social status were acceptable. If satisfied, a formal betrothal took place where a written agreement was signed and the couple kissed. Unlike modern times, the wedding day didn’t cement a lawful institution (marriage had no legal power) but showed the couple’s intent to live together. A Roman citizen couldn’t marry his favorite prostitute, cousin, or, for the most part, non-Romans. A divorce was granted when the couple declared their intention to separate before seven witnesses. If a divorce carried the accusation that the wife had been unfaithful, she could never marry again. A guilty husband received no such penalty.”[Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, August 5, 2016]

RELATED ARTICLES:

WEDDINGS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MARRIED LIFE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LOVE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

DIVORCE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMILY LIFE IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME: STATUS, INEQUALITY, LITERACY, RIGHTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROLES AND VIEWS OF WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian”

by Susan Treggiari (1991) Amazon.com;

“Marriage, Divorce, and Children in Ancient Rome” by Beryl Rawson (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Discourse of Marriage in the Greco-Roman World” by Jeffrey Beneker and Georgia Tsouvala (2020) Amazon.com;

“Marriage, Sex and Death: The Family and the Fall of the Roman West” by Emma Southon (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Wedding: Ritual and Meaning in Antiquity” by Karen Hersh (2010)

Amazon.com;

“The Roman Household: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Jane F. Gardner and Thomas Wiedemann (2013) Amazon.com;

“Women and the Law in the Roman Empire: A Sourcebook on Marriage, Divorce and Widowhood” (Routledge) by Judith Evans Grubbs (2002) Amazon.com;

“Women And Marriage During Roman Times Hardcover – May 22, 2010

by Maurice Pellison (1897) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History” by Jo-Ann Shelton, Pauline Ripat (1988) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Marriage in Early Ancient Rome

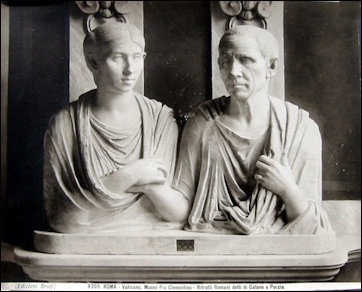

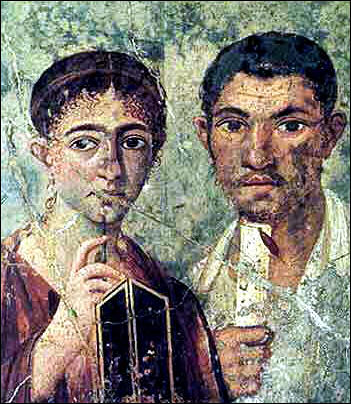

Pompeii couple Up to the time of the Servian constitution (traditional date, sixth century B.C.) patricians were the only citizens and intermarried only with patricians and with members of surrounding communities having like social standing. The only form of marriage known to them was called confarreatio. With the consent of the gods, while the pontifices celebrated the solemn rites, in the presence of the accredited representatives of his gens, the patrician took his wife from her father’s family into his own, to be a mater familias, to bear him children who should conserve the family mysteries, perpetuate his ancient race, and extend the power of Rome. By this, the one legal form of marriage of the time, the wife passed in manum viri, and the husband acquired over her practically the same rights as he would have over his own children and other dependent members of his family. Such a marriage was said to be cum conventione uxoris in manum viri. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

During this period, too, the free non-citizens, the plebeians, had been busy in marrying and giving in marriage. There is little doubt that their unions had been as sacred in their eyes, their family ties as strictly regarded and as pure as those of the patricians, but these unions were unhallowed by the national gods and unrecognized by the civil law, simply because the plebeians were not yet citizens. Their form of marriage, called usus, consisted essentially in the living together continuously of the man and woman as husband and wife, though there were probably conventional forms and observances, about which we know absolutely nothing.

The plebeian husband might acquire the same rights over the person and property of his wife as the patrician, but the form of marriage did not in itself involve manus. The wife might remain a member of her father’s family and retain such property as he allowed her by merely absenting herself from her husband for the space of a trinoctium, that is, three nights in succession, each year.1 If she did this, the marriage was sine conventione in manum, and the husband had no control over her property; if she did not, the marriage, like that of the patricians, was cum conventione in manum. |+|

Types of Marriage in Early Ancient Rome

Polygamy was never sanctioned at Rome. The ancient Egyptians were polygynous, whereas the ancient Romans generally were not. The Justinian Code proclaimed it an offense. There were exceptions, Marc Antony took two wives. One of them was Cleopatra, who had married her brother and was bound to Egyptian rather than Roman law.

While the patria potestas of the father over his children grew progressively weaker, it also ceased to arm the husband against his wife. In the old days, three separate forms of marriage had placed the wife under her husband's manus: 1) the confarreatio, or solemn offering by the couple of a cake of spelt (jarreus panis) in the presence of the Pontifex Maximus and the priest of the supreme god, the Flamen Dialis; 2) the coemptio, the fictitious sale whereby the plebeian father "mancipated" his daughter to her husband; and 3) finally the usus, whereby uninterrupted cohabitation for a year produced the same legal result between a plebeian man and a patrician woman. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

wedding

Coemptio was practiced by plebians. Under the fictitious sale, the pater familias (guardians) of the woman, or her tutor, if she was subject to one, transferred her to the man matrimonii causa. This form must have been a survival of the old custom of purchase and sale of wives, but we do not know when it was introduced among the Romans. It carried manus with it as a matter of course, and seems to have been regarded socially as better form than usus. The two existed for centuries side by side, but coemptio survived usus as a form of marriage cum conventione in manum.” |+|

It appears certain that none of these three forms had survived till the second century A.D. The usus had been the first to be given up, and it is probable that Augustus had formally abolished it by law. Confarreatio and coemptio were certainly practiced in the second century A.D., but seem to have been rather uncommon. Their place had been taken by a marriage which both in spirit and in -external form singularly resembles our own, and from which we may be permitted to assume that our own is derived.

This more modern form of marriage was preceded by a betrothal, which, however, carried no actual obligations. Betrothals were so common in the Rome of our epoch that Pliny the Younger reckons them among the thousand-and-one trifles which uselessly encumbered the days of his contemporaries. It consisted of a reciprocal engagement entered into by the young couple with the consent of their fathers and in the presence of a certain number of relatives and friends, some of whom acted as witnesses, while the rest were content to make merry at the banquet which concluded the festivities.

Requirements for a Legal Marriage in Ancient Rome

There were certain conditions that had to be satisfied before a legal marriage could be contracted even by citizens. The requirements were as follows: 1) The consent of both parties should be given, or that of the pater familias if one or both were in patria potestate. Under Augustus it was provided that the pater familias should not withhold his consent unless he could show valid reasons for doing so.

2) Both of the parties should be puberes; there could be no marriage between children. Although no precise age was fixed by law, it is probable that fourteen and twelve were the lowest limit for the man and the woman respectively. 3) Both man and woman should be unmarried. Polygamy was never sanctioned at Rome. 4) The parties should not be nearly related. The restrictions in this direction were fixed by public opinion rather than by law and varied greatly at different times, becoming gradually less severe. In general it may be said that marriage was absolutely forbidden between ascendants and descendants, between other cognates within the sixth (later the fourth) degree, and between the nearer adfines. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Pompeii silver“If the parties could satisfy these conditions, they might be legally married, but distinctions were still made that affected the civil status of the children, although no doubt was cast upon their legitimacy or upon the moral character of their parents. If the conditions were fulfilled and the husband and wife were both Roman citizens, their marriage was called iustae nuptiae, which we may translate by “regular marriage.” The children of such a marriage were iusti liberi and were by birth cives optimo iure, “possessed of all civil rights.”

“If one of the parties was a Roman citizen and the other a member of a community having the ius conubii but not full Roman civitas, the marriage was still called iustae nuptiae, but the children took the civil standing of the father. This means that, if the father was a citizen and the mother a foreigner, the children were citizens, but, if the father was a foreigner and the mother a citizen, the children were foreigners (peregrini), as was their father. |+|

“But if either of the parties was without the ius conubii, the marriage, though still legal, was called iniustae nuptiae or iniustum matrimonium, “an irregular marriage,” and the children, though legitimate, took the civil position of the parent of lower degree. We seem to have something analogous to this today in the loss of social standing which usually follows the marriage of one person with another of distinctly inferior position.” |+|

Marriage Laws in the Roman Empire

In attempt to boost the declining birth rate Augustus, in the A.D. 1st century, offered tax breaks for large families and cracked down on abortion. He imposed strict marriage laws and changed adultery from an act of indecency to an act of sedition, decreeing that a man who discovered his wife's infidelity must turn her in or face charges himself. Adulterous couples could have their property confiscated, be exiled to different parts of the empire and be prohibited from marrying one another. Augustus passed the reforms because he believed that too many men spent their energy with prostitutes and concubines and had nothing for their wives, causing population declines.

Under Augustus, women had the right to divorce. Husbands could see prostitutes but not keep mistresses, widows were obligated to remarry within two years, divorcees within 18 months. Parents with three or more children were given rewards, property, job promotions, and childless couples and single men were looked down upon and penalized . The end result of the reforms was a skyrocketing divorce rate.

Paul Halsall of Fordham University wrote: “Roman law developed as a mixture of laws, senatorial consults, imperial decrees, case law, and opinions issued by jurists. One of the most long lasting of actions” of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian' (A.D. 482-566) “was the gathering of these materials in the 530s into a single collection, later known as the Corpus Iuris Civilis [The Code of Civil Law]. The texts here address the issue of marriage, and date back particularly to the time of Augustus [ruled 27 B.C. - A.D. 14] who was very concerned about family matters and ensuring a large population. In the selections that follow the first part comes from the Digest and contain the opinions on marriage law of famous lawyers - Marcianus, Paulus, Terentius Clemens, Celsus, Modestinus, Gaius, Papinianus, Marcellus, Ulpianus, and Macer. Note that the most important were Papinianus (executed by the Emperor Caracalla in 212), who excelled at setting forth legal problems arising from cases, and Ulpianus (d. 223), who wrote a commentary on Roman law in his era. All these were legal scholars of the Roman imperial period whose works were considered important enough to keep in the Digest. [Source: “The Civil Law”, translated by S.P. Scott (Cincinnatis: The Central Trust, 1932), reprinted in Richard M. Golden and Thomas Kuehn, eds., “Western Societies: Primary Sources in Social History,” Vol I, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993), with indication that this text is not under copyright on p. 329]

1) Gaius, On the Lex Julia et Papia, Book II: “A pretended marriage is of no force or effect....? 2) Modestinus, On the Rite of Marriage. In unions of the sexes, it should always be considered not only what is legal, but also what is decent. 3) Modestinus, On the Rite of Marriage. If the daughter, granddaughter, or great-granddaughter of a senator should marry a freedman, or a man who practices the profession of an actor, or whose father or mother did so, the marriage will be void. [Lex Julia is an ancient Roman law that was introduced by any member of the Julian family. Most often it refers to moral legislation introduced by Augustus in 23 B.C., or to a law from the dictatorship of Julius Caesar]

Papinianus, Opinions, Book IV: 1) Where a general commission has been given to a man by someone to seek husband for his daughter, this is not sufficient ground for the conclusion a marriage. Therefore it is necessary that the person selected should be introduced to the father, and that he should consent to the marriage, order for it to be legally contracted....2) Marriage can be contracted between stepchildren, even though the have a common brother, the issue of the new marriage of their parents. 3) Where the daughter of a senator marries a freedman, this unfortanate act of her father does not render her a wife, for children should not be deprived of their rank on account of an offence of their parent....

Celsus, Digest, Book XXX: It is provided by the Lex Papia that all freeborn men, except senators an their children, can marry freedwomen. Modestinus, Rules, Book II. A son who has been emancipated can marry without the consent of his father, and any son that he may have will be his heir. Marcianus, Institutes, Book X: A patron cannot marry his freedwoman against her consent. [Source: “The Civil Law”, translated by S.P. Scott (Cincinnatis: The Central Trust, 1932), reprinted in Richard M. Golden and Thomas Kuehn, eds., “Western Societies: Primary Sources in Social History,” Vol I, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993), with indication that this text is not under copyright on p. 329]

Ulpianus, On the Lex Julia et Papia, Book III: In that law which provides that where a freedwoman has been married to her patron, after separation from him she cannot marry another without his consent; we understand the patron to be one who has bought a female slave under the condition of manumitting her (as is stated in the Rescript of our Emperor and his father), because, after having been manumitted, she becomes the freedwoman of the purchaser....

Augustus' Moral Legislation and Marriage

Along with attempts to restore the old Roman religion, Roman Emperor Augustus (ruled 27 A.D.–A.D. 14) wished to revive the old morality and simple life of the past. He himself disdained luxurious living and foreign fashions. He tried to improve the lax customs which prevailed in respect to marriage and divorce, and to restrain the vices which he felt were destroying the population of Rome. But it is difficult to say whether these laudable attempts of Augustus produced any real results upon either the religious or the moral life of the Roman people. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

In attempt to boost the declining birth rate Augustus offered tax breaks for large families and cracked down on abortion. He imposed strict marriage laws and changed adultery from an act of indecency to an act of sedition, decreeing that a man who discovered his wife's infidelity must turn her in or face charges himself. Adulterous couples could have their property confiscated, be exiled to different parts of the empire and be prohibited from marrying one another. Augustus passed the reforms because he believed that too many men spent their energy with prostitutes and concubines and had nothing for their wives, causing population declines.

Under Augustus, women had the right to divorce. Husbands could see prostitutes but not keep mistresses, widows were obligated to remarry within two years, divorcees within 18 months. Parents with three or more children were given rewards, property, job promotions, and childless couples and single men were looked down upon and penalized . The end result of the reforms was a skyrocketing divorce rate.

Betrothals and Dowries in Ancient Rome

Formal betrothal (sponsalia) as a preliminary to marriage was considered good form but was not legally necessary and carried with it no obligations that could be enforced by law. In the sponsalia the maiden was promised to the man as his bride with “words of style,” that is, in solemn form. The promise was made, not by the maiden herself, but by her pater familias, or by her tutor if she was not in patria potestate. In the same way, the promise was made to the man directly only in case he was sui iuris; otherwise it was made to the Head of his House, who had asked for him the maiden in marriage. The “words of style” were probably something like this:

“Spondesne Gaïam, tuam filiam (or, if she was a ward, Gaïam, Lucii filiam), mihi (or filio meo) uxorem dari?”

"Di bene vortant! Spondeo."

"Di bene vortant!” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“At any rate, the word spondeo was technically used of the promise, and the maiden was henceforth sponsa. The person who made the promise had always the right to cancel it. This was usually done through an intermediary (nuntius); hence the formal expression for breaking an engagement was repudium renuntiare, or simply renuntiare. While the contract was entirely one-sided, it should be noticed that a man was liable to infamia if he formed two engagements at the same time, and that he could not recover any presents made with a view to a future marriage if he himself broke the engagement. Such presents were almost always made. Though we find that articles for personal use, the toilet, etc., were common, a ring was usually given. The ring was worn on the third finger of the left hand, because it was believed that a nerve (or sinew) ran directly from this finger to the heart. It was also usual for the sponsa to make a present to her betrothed. |+|

“It was a point of honor with the Romans, as it is now with some European peoples, for the bride to bring to her husband a dowry (dos, Modem French dot). In the case of a girl in patria potestate this would be furnished by the Head of her House; in the case of one sui iuris it was furnished from her own property, or, if she had none, was contributed by her relatives. It seems that if they were reluctant she might by process of law compel her ascendants at least to furnish it. In early times, when marriage cum conventione prevailed, all the property brought by the bride became the property of her husband, or of his pater familias, but in later times, when manus was less common, and especially after divorce had become of frequent occurrence, a distinction was made. A part of the bride’s possessions was reserved for her own exclusive use, and a part was made over to the groom under the technical name of dos. The relative proportions varied, of course, with circumstances.” |+|

Marriage Formalities in Ancient Rome

There were really no legal forms necessary for the solemnization of a marriage; there was no license to be procured from the civil authorities; the ceremonies, simple or elaborate, did not have to be performed by persons authorized by the State. The one thing necessary was the consent of both parties, if they were sui iuris, or of their patres familias, if they were in patria potestate. It has been remarked that the pater familias could refuse his consent for valid reasons only; on the other hand, he could command the consent of persons subject to him. Parental and filial affection (pietas) made this hardship much less rigorous than it now seems to us. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

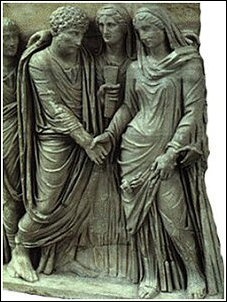

“But, though this consent was the only condition for a legal marriage, it had to be shown by some act of personal union between the parties, that is, the marriage could not be entered into by letter or by messenger or by proxy. Such a public act was the joining of hands (dextrarum iunctio) in the presence of witnesses, or the bride’s act in letting herself be escorted to her husband’s house, never omitted when the parties had any social standing, or, in later times, the signing of the marriage contract. It was never necessary to a valid marriage that the parties should live together as man and wife, though, as we have seen, this living together of itself constituted a legal marriage. |+|

Weddings in Ancient Rome

The Roman wedding ceremony incorporated as a series of divine and human rituals. The bride wore an orange veil, which symbolized dawn, and a white or orange dress with a belt or girdle tied into the "knot of Hercules," which the husband untied on their wedding night. The expression "tie the knot" is a reference to this belt. The custom of a June wedding is linked to Juno, the goddess of marriage and childbirth, after which the month of June was named.

It will be noticed that superstition played an important part in the arrangements for a wedding two thousand years ago, as it does now. Especial pains had to be taken to secure a lucky day. The Kalends, Nones, and Ides of each month, and the day following each of them, were unlucky. So was all of May and the first half of June, on account of certain religious ceremonies observed in these months, in May the Argean offerings and the Lemuria, in June the dies religiosi connected with Vesta. Besides these, the dies parentales, February 13-21, and the days when the entrance to the lower world was supposed to be open, August 24, October 5, and November 8, were carefully avoided.

One-third of the year, therefore, was absolutely barred. The great holidays, too, and these were legion, were avoided, not because they were unlucky, but because on these days friends and relatives were sure to have other engagements. Women being married for the second time chose these very holidays to make their weddings less conspicuous. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

See Separate Article: WEDDINGS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Ius Conubii: Rules of Marriage Between Patricians and Plebians

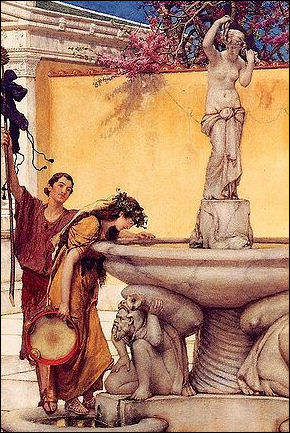

Between Venus and Bacchus

by Alma-Tadema Though the Servian constitution made the plebeians citizens and thereby legalized their forms of marriage, it did not give them the right of intermarriage with the patricians. Many of the plebeian families were hardly less ancient than the patricians, many were rich and powerful, but it was not until 445 B.C. that marriages between the two Orders were formally sanctioned by the civil law. The objection on the part of the patricians was largely a religious one: the gods of the State were gods of the patricians, the auspices could be taken by patricians only, the marriages of patricians only were sanctioned by heaven. Their orators protested that the unions of the plebeians were not marriages at all, not iustae nuptiae; the plebeian wife, they insisted, was only taken in matrimonium: she was at best only an uxor, not a mater familias; her offspring were “mother’s children,” not patricii. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Much of this was class exaggeration, but it is true that for a long time the gens was not so highly valued by the plebeians as by the patricians, and that the plebeians assigned to cognates certain duties and privileges that devolved upon the patrician gentiles. With the extension of the ius conubii many of these points of difference disappeared. New conditions were fixed for iustae nuptiae; coemptio by a sort of compromise became the usual form of marriage when one of the parties was a plebeian; and the stigma disappeared from the word matrimonium. On the other hand, patrician women learned to understand the advantages of a marriage sine conventione in manum, and marriage with manus grew less frequent, the taking of the auspices before the ceremony came to be considered a mere form, and marriage began to lose its sacramental character. With these changes came later the laxness in the marital relation and the freedom of divorce that seemed in the time of Augustus to threaten the very life of the commonwealth. |+|

“It is probable that by the time of Cicero marriage with manus was uncommon, and consequently that confarreatio and coemptio had gone out of general use. To a limited extent, however, the former was retained into Christian times, because certain priestly offices (those of the flamines maiores and the reges sacrorum) could be filled only by persons whose parents had been married by the confarreate ceremony, the sacramental form, and who had themselves been married by the same form. Augustus offered exemption from manus to mothers of three children, but this was not enough, for so great became the reluctance of women to submit to manus that in order to fill even these few priestly offices it was found necessary under Tiberius to eliminate manus from the confarreate ceremony. |+|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024