FOOD IN ANCIENT ROME

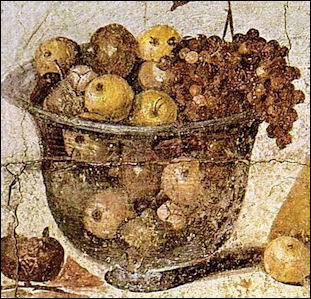

House of Julia Felix still life

of wine and fruit from PompeiiRome was praised by Virgil in 29 B.C. for its grain, wine, olives and "prosperous herds." Food was never a problem in Rome. The land around the city was productive and as the empire expanded it was fed by fertile land in Tunis and Algeria.

Roman cuisine is often associated with over gluttony and over-the-top indulgence, with lark’s tongues and stuffed dormice and the like but what ordinary people ate a regular basis is much more mundane: typically millet or wheat-based porridge, seasoned with herbs or meat if available. Archaeologists excavating Herculaneum near Pompeii, studying what Romans ate by examining what they left behind in their sewers and sifting through hundreds of sacks of human excrement, determined that Romans ate a lot of vegetables. “Dr Annamaria Ciarallo, an environmental biologist and researcher at Pompeii, told Tribune News said: “The food then was mainly based on cereals, vegetables, cheese and fish, with just a little meat. It was very healthy – the original Mediterranean diet.”

Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “The diet of the inhabitants of Vindolanda [in Britain] was pretty varied. Within the Vindolanda tablets, 46 different types of foodstuff are mentioned. Whilst the more exotic of these, such as roe deer, venison, spices, olives, wine and honey, appear in the letters and accounts of the slaves attached to the commander's house; it is clear that the soldiers and ordinary people around the fort did not eat badly. We have already seen the grain accounts of the brothers Octavius and Candidus, demonstrating that a wide variety of people in and around the fort were supplied with wheat. Added to that are a couple of interesting accounts and letters which show that the ordinary soldiers could get hold of such luxuries as pepper and oysters, and that the local butcher was doing a roaring trade in bacon. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, November 16, 2012 ]

Carbonized eggs and bread have been found in excavations in Pompeii. Dr Joanne Berry wrote for the BBC: “ Such finds are very rare, since organic materials generally have not survived. There is only limited evidence of goods such as food, wooden furniture and cloth (for clothes, or drapery) that were essential to everyday life, yet were made of perishable materials. It does appear from the available evidence, however, that the inhabitants of Pompeii had a varied diet. Other preserved foods that have been discovered include bread, walnuts, almonds, dates, figs and olives. Many animal bones (sheep, pig, cattle), fish bones and shells (scallop, cockle, sea urchin, cuttlefish) also have been uncovered.” [Source: Dr Joanne Berry, Pompeii Images, BBC, March 29, 2011]

Common Foods in the Roman Empire

bread from Pompeii

Among other things Romans ate doves, chickens, figs, dates, olives, grapes, white almonds, truffles and fois gras and cooked fowl in clay pots. There were no tomatoes, potatoes, spaghetti, risotto, or corn. Romans often turned up their noses at the food from outside Rome. On the food in Greece a character in a satire commented: “They give weeds to their guests, as though they were cattle. And they flavor their weeds with other weeds."

Major crops included grapes, olives, peaches, cherries, plums and walnuts.Romans grafted apple trees and spread apple cultivation throughout their empire. The main pieces of farm machinery were olive oil presses. Rabbits are believed to have been domesticated using wild rabbits from Iberia in the Roman Era.

The Romans consumed dairy products such as milk, cream, curds, whey, and cheese. Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “ They drank the milk of sheep and goats as well as that of cows, and made cheese of the three kinds of milk. The cheese from ewes’ milk was thought more digestible, though less palatable, than that made from cows’ milk, while cheese from goats’ milk was more palatable but less digestible. It is remarkable that they had no knowledge of butter except as a plaster for wounds. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

“Honey took the place of sugar on the table and in cooking, for the Romans had only a botanical knowledge of the sugar cane. Salt was at first obtained by the evaporation of sea water, but was afterwards mined, Its manufacture was a monopoly of the government, and care was taken always to keep the price low. It was used not only for seasoning, but also as a preservative agent. Vinegar was made from grapes. Among the articles of food unknown to the Romans were tea and coffee, along with the orange, tomato, potato, butter, and sugar.” |+|

Categories with related articles in this website: Early Ancient Roman History (34 articles) factsanddetails.com; Later Ancient Roman History (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Life (39 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Art and Culture (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Government, Military, Infrastructure and Economics (42 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ;

“Outlines of Roman History” forumromanum.org; “The Private Life of the Romans” forumromanum.org|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu;

Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org

The Roman Empire in the 1st Century pbs.org/empires/romans;

The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ;

Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors roman-emperors.org;

British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;

Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art;

The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ;

Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu;

Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ;

History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame /web.archive.org ;

United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Natural Conditions in Italy for Producing Food

Winter food Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “Italy is blessed above all the other countries of central Europe with the natural conditions that go to yield an abundant and varied supply of food. The soil is rich and composed of different elements in different parts of the country. The rainfall is abundant, and rivers and smaller streams are numerous. The line of greatest length runs northwest to southeast, but the climate depends little upon latitude, as it is modified by surrounding bodies of water, by mountain ranges, and by prevailing winds. These agencies in connection with the varying elevations of the land itself produce such widely different conditions that somewhere within the confines of Italy almost all the grains and fruits of the temperate and subtropic zones find the soil and climate most favorable to their growth. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

“The earliest inhabitants of the peninsula, the Italian peoples, seem to have left for the Romans the task of developing and improving these means of subsistence. Wild fruits, nuts, and flesh have always been the support of uncivilized peoples, and must have been so for the shepherds who laid the foundations of Rome. The very word pecunia (from pecu; cf. peculium), shows that herds of domestic animals were the first source of Roman wealth. But other words show just as clearly that the cultivation of the soil was understood by the Romans in very early times: the names Fabius, Cicero, Piso, and Caepio are no lessancient than Porcius, Asinius, Vitellius, and Ovidius. Cicero puts into the mouth of the Elder Cato the statement that to the farmer the garden was a second meat supply, but long before Cato’s time meat had ceased to be the chief article of food. Grain and grapes and olives furnished subsistence for all who did not live to eat. These gave “the wine that maketh glad the heart of man, and oil to make his face to shine, and bread that strengtheneth man’s heart.” On these three abundant products of the soil the mass of the people of Italy lived of old as they live today. Something will be said of each, after less important products have been considered.” |+|

Food also came from elsewhere in the Mediterranean. A satirical poem by Varro, a contemporary of Cicero, lists peacock from Samos, heath-cock from Phrygia, crane from Media, kid from Ambracia, young tunny-fish from Chalcedon, murena from Tartessus, cod from Pessinus, oysters from Tarentum, scallops from Chios, sturgeon from Rhodes, scarus from Cilicia, nuts from Thasos, dates from Egypt, and chestnuts from Spain. |+|

Ancient Roman Dishes, Exotic Food and Desserts

Romans liked putrid fish sauces and ate sweet-and-sour, spicy and curry-like dishes. Appetizers included salted fish, pigs’ feet, hard boiled eggs, and stuffed artichokes. The Romans regarded honey as a medicine and drank coriander mixed with honey as a remedy for childbirth fever. The Romans also ate insects. Pliny wrote they were particularly fond of grubs called cossus, which he said could be made into “the most delicate dishes." They didn't eat horse meat.

snails

Among the desserts consumed by Romans were fruit and custard in honey-sweetened goodies. Chilled fruit juices, milk and honey were enjoyed in the time of Alexander the Great (4th century B.C.). Nero (1st century A.D.) ate desserts made from snow brought in from the mountains. The earliest known cookies were made in Rome in the third century B.C. They were unleavened, bland, hard wafers. The words “cookie” and “biscuit” are derived from the Latin word bis coctum, which means "twice baked." Roman cookies were often dipped in wine to soften them up.

Romans hosted elaborate dinner parties with hosts trying to top one another with the most elaborate dishes. They ate ostrich brains, peacocks, dolphin meatballs, herons, goat feet, peacock brains, boiled parrot, flamingo tongues and orioles. They liked watching birds fly out of featured dishes and ate an electric fish because “it was fascinating." Sometimes a calf was cooked up with a pig inside it and inside the pig were a lamb, a chicken, a rabbit and a mouse. The Roman Emperor Elagabalus once ordered 600 ostriches killed so his cooks could make him ostrich-brain pies.

The Roman elite indulged themselves with unusual foods such as nightingale tongues, parrot heads, camel heels and elephant trunks. One of the greatest delicacies was foie gras made by force feeding geese with figs to enlarge their livers. The Roman are sometimes credited with inventing foie gras, but the Greeks also ate it.

Evidence of Romans Dining on Giraffe and Other Exotica

Excavations in Pompeii have provided hard evidence that ancient Romans dined on giraffes, pink flamingos and exotic spices from as far away as Indonesia, according to a study of food waste examined by researchers from the University of Cincinnati led by archaeologist Steven Ellis. AFP reported: “The most used foods found in drains and dumps were grains, fruits, nuts, olives, lentils, local fish and eggs, but there was also more exotic fare like salted fish from Spain, or imported shellfish and sea urchins. [Source: AFP, January 8, 2014 /*/]

“A joint of giraffe was found in the drain of one home. “This is thought to be the only giraffe ever recorded from an archaeological excavation in Roman Italy,” Ellis said. “Ellis’s team has been working on two neighbourhoods of Pompeii for over 10 years. The area had around 20 shops, most of which served food and drink, and the archaeologists analyzed their waste drains as well as nearby latrines and cesspits. The remains go back as far as the 4th century B.C. Ellis said that Pompeii urbanites had “a higher fare and standard of living” than previously thought and the university said the research was “wiping out the historic perceptions of how the Romans dined.” Ellis’s discoveries were presented at the joint annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) and American Philological Association (APA) in Chicago. /*/

camel-like giraffe in a 5th-century Roman-Byzantine church in Petra, Jordan

According to a University of Cincinnati press release: “Ellis says the excavation is producing a complete archaeological analysis of homes, shops and businesses at a forgotten area inside one of the busiest gates of Pompeii, the Porta Stabia. The area covers 10 separate building plots and a total of 20 shop fronts, most of which served food and drink. The waste that was examined included collections from drains as well as 10 latrines and cesspits, which yielded mineralized and charred food waste coming from kitchens and excrement. Ellis says among the discoveries in the drains was an abundance of the remains of fully-processed foods, especially grains.

“The material from the drains revealed a range and quantity of materials to suggest a rather clear socio-economic distinction between the activities and consumption habits of each property, which were otherwise indistinguishable hospitality businesses,” says Ellis. Findings revealed foods that would have been inexpensive and widely available, such as grains, fruits, nuts, olives, lentils, local fish and chicken eggs, as well as minimal cuts of more expensive meat and salted fish from Spain. Waste from neighboring drains would also turn up less of a variety of foods, revealing a socioeconomic distinction between neighbors. [Source: University of Cincinnati]

“A drain from a central property revealed a richer variety of foods as well as imports from outside Italy, such as shellfish, sea urchin and even delicacies including the butchered leg joint of a giraffe. “That the bone represents the height of exotic food is underscored by the fact that this is thought to be the only giraffe bone ever recorded from an archaeological excavation in Roman Italy,” says Ellis. “How part of the animal, butchered, came to be a kitchen scrap in a seemingly standard Pompeian restaurant not only speaks to long-distance trade in exotic and wild animals, but also something of the richness, variety and range of a non-elite diet.”

“Deposits also included exotic and imported spices, some from as far away as Indonesia. Ellis adds that one of the deposits dates as far back as the 4th century B.C., which he says is a particularly valuable discovery, since few other ritual deposits survived from that early stage in the development of Pompeii. “The ultimate aim of our research is to reveal the structural and social relationships over time between working-class Pompeian households, as well as to determine the role that sub-elites played in the shaping of the city, and to register their response to city-and Mediterranean-wide historical, political and economic developments. However, one of the larger datasets and themes of our research has been diet and the infrastructure of food consumption and food ways,” says Ellis. “He adds that as a result of the discoveries, “The traditional vision of some mass of hapless lemmings – scrounging for whatever they can pinch from the side of a street, or huddled around a bowl of gruel – needs to be replaced by a higher fare and standard of living, at least for the urbanites in Pompeii.”

Roman Food That the British Ate and Americans Would Recognize

mushrooms

Adam Hart-Davis wrote for the BBC: “Celtic cooking had probably been a one-pot affair, such as a mess of potage to be shared by the household, but the Romans introduced the three-course meal. They cooked meat, fish and eggs and brought with them apples, pears, apricots, turnips, carrots, coriander and asparagus. They brought recipes too - I can strongly recommend the kidneys stuffed with herbs and the fishy custard.” [Source: Adam Hart-Davis, BBC, February 17, 2011]

On what the Roman Britons, Tom Whipple wrote in the Sunday Times: 1) “Porridgey gruel: The ultimate peasant food low in refined sugar, almost impossible to get obese on, you know what they say, nothing tastes as good as thin feels. And gruel feels pretty thin.” 2) “Bread: Ward off diabetes the ancient Briton way, by chewing continuously on gritty, tough and mind-numbingly tedious bread made from poorly milled flour. Calorifically, you barely break even. 3) “Broth: It might not have the richness of modern soups, but as far as your oral hygiene is concerned it will keep you smiling to the very end. If, that is, you can get over the unrelenting misery of your diet.” [Source: Tom Whipple, Sunday Times, October 2014]

Joel N. Shurkin wrote in insidescience: “Archaeologists studying the eating habits of ancient Etruscans and Romans have found that pork was the staple of Italian cuisine before and during the Roman Empire. Both the poor and the rich ate pig as the meat of choice, although the rich got better cuts, ate meat more often and likely in larger quantities. They had pork chops and a form of bacon. They even served sausages and prosciutto.... Besides the meat, there would be vegetables that looked little different from what we eat, said Angela Trentacoste of the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom. Except for grain, which was imported in huge quantities from places like North Africa, everything was locally grown.... Pizza had yet not been invented.” [Source: Joel N. Shurkin, insidescience, February 3, 2015 +/]

Diet in Ancient Rome Determined by Class

The massive feasts and exotic delicacies for which Rome is famed were enjoyed only by the upper classes. Most of the remaining populations ate a diet consisting primarily of course grains like wheat and millet. Despite living near the seas, lower-class Romans appear to have eaten very little fish or seafood and suffered from a variety of diet-related health problems such as anemia and poor dental hygiene. City dwellers appear to have eaten better than people in rural areas and the further from Rome one lived the worse their diet was.

.jpg)

food table (imitation) “Health studies have heralded the modern Mediterranean diet, rich in olive oil, fish and nuts, as a good way to avoid heart disease. Stephanie Pappas wrote in Live Science: “In ancient Rome, however, diet varied based on social class and where a person lived. Ancient texts have plenty to say about lavish Roman feasts. The wealthy could afford exotic fruits and vegetables, as well as shellfish and snails. A formal feast involved multiple dishes, eaten from a reclined position, and could last for hours. But ancient Roman writers have less to say about the poor, other than directions for landowners on the appropriate amount to feed slaves, who made up about 30 percent of the city’s population. Killgrove wanted to know more about lower-class individuals and what they ate. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, March 1, 2013 ^^]

“There were also differences among people living within Rome. Individuals buried in the mausoleum at Casa Bertone (a relatively high-class spot, at least for commoners), ate less millet than those buried in the simple cemetery surrounding Casa Bertone’s mausoleum. Meanwhile, those buried in the farther-flung Castellaccio Europarco cemetery ate more millet than anyone at Casa Bertone, suggesting they were less well-off than those living closer to or within the city walls.” ^^

Most Romans Ate No Better Than Their Livestock Animals

Stephanie Pappas wrote in Live Science: “Ancient Romans are known for eating well, with mosaics from the empire portraying sumptuous displays of fruits, vegetables, cakes — and, of course, wine. But the 98 percent of Romans who were non-elite and whose feasts weren’t preserved in art may have been stuck eating birdseed. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, March 1, 2013 ^^]

“Common people in ancient Rome ate millet, a grain looked down upon by the wealthy as fit only for livestock, according to a new study published in the March issue of the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. And consumption of millet may have been linked to overall social status, with relatively poorer suburbanites eating more of the grain than did wealthier city dwellers. The results come from an analysis of anonymous skeletons in the ancient city’s cemeteries. “We don’t know anything about their lives, which is why we’re trying to use biochemical analysis to study them,” said study leader Kristina Killgrove, an anthropologist at the University of West Florida. ^^

Stephanie Pappas wrote in Live Science: ““Historical texts dismiss millet as animal feed or a famine food, Killgrove said, but the researcher’s findings suggest that plenty of ordinary Romans depended on the easy-to-grow grain. One man, whose isotope ratios showed him to be a major millet consumer, was likely an immigrant, later research revealed. He may have been a recent arrival to Rome when he died, carrying the signs of his country diet with him. Or perhaps he kept eating the food he was used to, even after arriving in the city.” ^^

Roman Diet Nutritionally Poor Because of Lack of Milk

An Oxford study of the remains of almost 20,000 people dating from the 8th century B.C. to the A.D. 18th century found that the Roman period was a time of poor nutrition and low average height levels. Why?: A lack of milk and dairy products. This trend was reversed in the Dark Ages after the fall of the Roman Empire. [Source:Jamie Doward, The Guardian, April 2010]

Jamie Doward wrote in The Guardian: “The key factor in determining average height over the centuries – an indicator of nutritional status and wellbeing – has been an increase in milk consumption due to improved farming. Higher population densities and the need to feed the army during Roman times may have worked against this.*\

“The “anthropometric” approach pursued by Nikola Koepke of Oxford University, which combines biology and archaeology, suggests longer bone length is indicative of improved diet. Koepke’s study, presented at the Economic History Society’s 2010 annual conference, also challenges assumptions about the effect of the industrial revolution. Urbanisation did not improve wellbeing, she argues, at least as measured by height.

“Rather, Koepke says, the key factor in determining average height growth over the past 2,500 years has been the increased consumption of milk as a result of the spread of, and improvements in, farming. She found that overall European living conditions improved slightly in the past 2,500 years even in the centuries prior to the industrial revolution. *\

“Her study is based on data compiled from analysing the skeletal remains of more than 18,500 individuals of both genders from all social classes, from 484 European archaeological dig sites. “Higher milk consumption as indicated by cattle share had a positive impact on mean height,” Koepke writes. “Correspondingly, this determinant is the key factor in causing significant European regional differences in mean height.”“ *\

Food Subsidies in Ancient Rome

Bruce Bartlett wrote in the Cato Institute Journal: “The reason why Egypt retained its special economic system and was not allowed to share in the general economic freedom of the Roman Empire is that it was the main source of Rome’s grain supply. Maintenance of this supply was critical to Rome’s survival, especially due to the policy of distributing free grain (later bread) to all Rome’s citizens which began in 58 B.C. By the time of Augustus, this dole was providing free food for some 200,000 Romans. The emperor paid the cost of this dole out of his own pocket, as well as the cost of games for entertainment, principally from his personal holdings in Egypt. The preservation of uninterrupted grain flows from Egypt to Rome was, therefore, a major task for all Roman emperors and an important base of their power. [Source: Bruce Bartlett, “How Excessive Government Killed Ancient Rome,” Cato Institute Journal 14: 2, Fall 1994, Cato.org /=]

Moretum, a common Roman food“The free grain policy evolved gradually over a long period of time and went through periodic adjustment. 3 The genesis of this practice dates from Gaius Gracchus, who in 123 B.C. established the policy that all citizens of Rome were entitled to buy a monthly ration of corn at a fixed price. The purpose was not so much to provide a subsidy as to smooth out the seasonal fluctuations in the price of corn by allowing people to pay the same price throughout the year. /=\

“Under the dictatorship of Sulla, the grain distributions were ended in approximately 90 B.C. By 73 B.C., however, the state was once again providing corn to the citizens of Rome at the same price. In 58 B.C., Clodius abolished the charge and began distributing the grain for free. The result was a sharp increase in the influx of rural poor into Rome, as well as the freeing of many slaves so that they too would qualify for the dole. By the time of Julius Caesar, some 320,000 people were receiving free grain, a number Caesar cut down to about 150,000, probably by being more careful about checking proof of citizenship rather than by restricting traditional eligibility. /=\

“Under Augustus, the number of people eligible for free grain increased again to 320,000. Tn 5 B.C., however, Augustus began restrictingthe distribution. Eventually the number ofpeople receiving grain stabilized at about 200,000. Apparently, this was an absolute limit and corn distribution was henceforth limited to those with a ticket entitling them to grain. Although subsequent emperors would occasionally extend eligibility for grain to particular groups, such as Nero’s inclusion ofthe Praetorian guard in 65 AD., the overall number of people receiving grain remained basically fixed. /=\

“The distribution of free grain in Rome remained in effect until the end of the Empire, although baked bread replaced corn in the 3rd century. Under Septimius Severus (193—211 AD.) free oil was also distributed. Subsequent emperors added, on occasion, free pork and wine. Eventually, other cities of the Empire also began providing similar benefits, including Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch. /=\

“Nevertheless, despite the free grain policy, the vast bulk of Rome’s grain supply was distributed through the free market. There are two main reasons for this. First, the allotment of free grain was insufficient to live on. Second, grain was available only to adult male Roman citizens, thus excluding the large number of women, children, slaves, foreigners, and other non-citizens living in Rome. Government officials were also excluded from the dole for the most part. Consequently, there remained a large private market for grain which was supplied by independent traders.” /=\

Determining What Romans Ate From Their Skeletons, Garbage and Feces

Stephanie Pappas wrote in Live Science: ““To find out, she and her colleagues analyzed portions of bones from the femurs of 36 individuals from two Roman cemeteries. One cemetery, Casal Bertone, was located right outside the city walls. The other, Castellaccio Europarco, was farther out, in a more suburban area. The skeletons date to the Imperial Period, which ran from the first to the third century A.D., during the height of the Roman Empire. At the time, Killgrove told LiveScience, between 1 million and 2 million people lived in Rome and its suburbs. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, March 1, 2013 ^^]

Roman garbage

“To determine diets from the Roman skeletons, the researchers analyzed the bones for isotopes of carbon and nitrogen. Isotopes are atoms of an element with different numbers of neutrons, and are incorporated into the body from food. Such isotopes of carbon can tell researchers which types of plants people consumed. Grasses such as wheat and barley are called C3 plants; they photosynthesize differently than mostly fibrous C4 plants, such as millet and sorghum. The differences in photosynthesis create different ratios of carbon isotopes preserved in the bones of the people who ate the plants. ^^

“Nitrogen isotopes, on the other hand, give insight into the kinds of protein sources people ate. “We found that people were eating very different things,” Killgrove said. Notably, ancient Italians were locavores. Compared with people living on the coasts, for example, the Romans ate less fish.” ^^

Zooarchaeologists, scientists study the remains of animals found in archaeological sites. Joel N. Shurkin wrote in insidescience: “They rummaged through ancient garbage dumps or middens, and occasionally even ancient latrines looking for the bones of animals and fish people ate. People would sometimes dump the garbage in the latrine instead of walk to the neighborhood dump, MacKinnon said. They can deduce a great deal from the bones about what life was like. They also can often piece together a typical diet based on recovered porcelain shards. “They can look at bones in a dump and can tell what the animal was, sometimes how it was slaughtered, where it came from, and how the food supply worked. “For instance, if one site had nothing but feet bones, “It tells us that things were marketed and better cuts went elsewhere,” he said. [Source: Joel N. Shurkin, insidescience, February 3, 2015 +/]

Gum Disease and Tooth Decay in Roman-Era Britain

Contrary to what you might think, Roman-era Britons had less gum disease than their 21st-century conterparts Tom Whipple wrote in the Sunday Times: “An analysis of the skulls of more than 300 Roman Britons has found a significantly lower rate of periodontitis, a common form of gum disease, than exists in today’s population. Among those examined – who were originally buried in a site in Poundbury, Dorset – between 5 per cent and 10 per cent had the disease, compared with 15 per cent to 30 per cent today. [Source: Tom Whipple, Sunday Times, October 2014 -]

“However, they also had considerably more evidence of abrasion on their teeth, probably a result of the diet of coarse grains that was common. The work involved looking at the sockets holding the teeth into the jaw. “Because gum disease causes disruption of the bone around the teeth, we are able to measure it,” said Francis Hughes, professor of periodontology at King’s college London. “He and his colleagues learnt that the Natural History Museum had a large collection of skeletons from the Poundbury burial site, and asked to analyse them. “To a lot of people’s surprise they had quite a lot less periodontitis than the modern human population. It was about a third as common as today,” Professor Hughes said. Some of the explanation for this does not exactly provide cause for envy: the Ancient Britons managed to contract even more serious diseases first, and died of those instead of suffering through old age with bad teeth. -

copy of an ancient Roman denture

“The most common age at death appeared to be in the 40’s. The reason for the modern mouth to be unhealthier than it was centuries ago is probably a result of two things – diabetes and smoking. “Those two change the risk enormously,” Professor Hughes said. Periodontitis starts as gingivitis, a consequence of poor brushing that often manifests as bleeding and inflamed gums. This response is actually a protective mechanism. “It’s the body trying to fight the bacteria off. In smoking and diabetes that protective mechanism is decreased – the body is less able to fight,” Professor Hughes said. Starting with bleeding, the disease progresses through receding gums, looseness of teeth and eventually total tooth loss. With a life free not just from smoking and diabetes but also from refined sugar, the Poundbury teeth were similarly less affected by cavities. -

“Nevertheless, the research, published in the British Dental Journal, did not find that the oral hygiene of Ancient Britons was entirely something to be aspired to. “Decay was not widespread like it might be today,” Professor Hughes said. “But it was still there, probably a consequence of the starchy cereals they ate. Over the years that increased bacterial growth” Where decay did exist, it went unchecked. Some teeth had decayed to the point where they had infected the nerve, while others caused holes down to the jaw itself. “The amount of chronic infection must have caused a lot of misery,” Professor Hughes said. His profession would have been in demand even in that day and age, he added. “It’s still a rather good advert for dentists.” -

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except garbage, Archaeology News Network

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~\; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018