SEX IN ANCIENT ROME

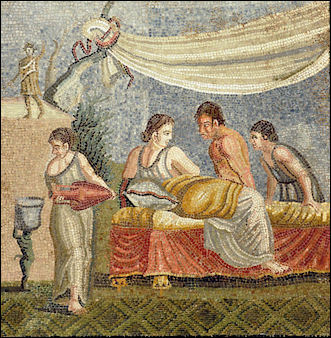

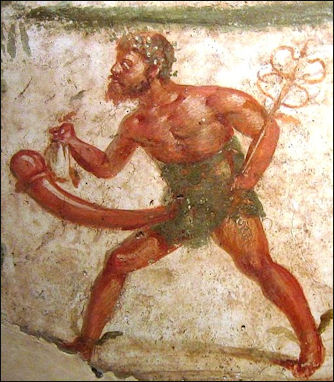

Sex was a common theme in Roman art and literature. Ovid once wrote, "Offered a sexless heaven, I's say no thank you, women are such sweet hell." The poet Propertius wrote in great detail about his sexual relations with his girlfriend Hostia. One fresco in Pompeii shows a guy with a penis so big it is held up by a string. An erotic stucco mosaic from Pompeii features a couple having sexual intercourse sitting down.

Men often boasted of their love-making adventures on the walls of baths and other public buildings. Graffiti scrawled on the wall of a Pompeii bar claimed: 'I fucked the landlady.' Graffiti was often filled with bawdy and graphic details. The writers were not shy about naming names and even saying the time and place that encounters took place. Men who preferred men seemed just as emboldened to list their conquests and as men who preferred women.

The Roman God Priapus had an enormous penis. He is sometimes pictured chasing after vestal virgins. There was secret cult that worshipped him. In classical Latin the word "vagina" means "sheath for a sword." There is one story that when Caesar put his sword into its scabbard he said he was putting it into its vagina. In the “Natural History of Love,” Diane Ackerman said that Aeneas put his sword in “his” vagina in the Aeneid. Some scholars have said that “vagina’ here meant a wound. And, there were two Latin words for large breasts: mammosa and mammeata.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HISTORY OF SEX IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PRIAPUS AND PHALLUSES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ORAL SEX AND SEX POSITIONS IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

MASTURBATION, SODOMY, MIRRORS AND BESTIALITY IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PROSTITUTES AND BROTHELS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ADULTERY IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OVER-SEXED EMPERORS AND THEIR FAMILY MEMBERS europe.factsanddetails.com

GAY MEN AND LESBIANS IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

SEX POETRY FROM ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Sex: 100 B.C. to A.D. 250" by John Clarke and Michael Larvey (2003) Amazon.com;

“Sex and Sexuality in Ancient Rome” by L J Trafford (2021) Amazon.com;

“Controlling Desires: Sexuality in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Kirk Ormand (2018) Amazon.com;

“Sex on Show: Seeing the Erotic in Greece and Rome” by Caroline Vout (2013) Amazon.com;

“Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture” by Marilyn B. Skinner Amazon.com;

“Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Literature: A Sourcebook” (Routledge)

by Marguerite Johnson (2022) Amazon.com;

“Sex Lives of the Roman Emperors by Nigel Cawthorne (2006) Amazon.com;

“Caesars' Wives: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Roman Empire”, Illustrated, by Annelise Freisenbruch (2011) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Sexualities: A Sourcebook” (Bloomsbury Sources) by Jennifer Larson (2012) Amazon.com;

“Sex in Antiquity: Exploring Gender and Sexuality in the Ancient World” by Mark Masterson, Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, et al. (2018) Amazon.com;

“Sex and Difference in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Mark Golden and Peter Toohey (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Sleep of Reason: Erotic Experience and Sexual Ethics in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Martha C. Nussbaum , Juha Sihvola (2002) Amazon.com;

The Erotic Poems (Penguin Classics) by Ovid and Peter Green (1983) Amazon.com;

“From Good Goddess to Vestal Virgins: Sex and Category in Roman Religion”

by Ariadne Staples | Feb 1, 2013 Amazon.com;

“Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity” by Sarah Pomeroy (1995) Amazon.com;

“Women's Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation” by Maureen B. Fant and Mary R. Lefkowitz (2016) Amazon.com;

“Love in Ancient Rome” by Pierre Grimal (1986) Amazon.com;

“In the Orbit of Love: Affection in Ancient Greece and Rome” by David Konstan (2018) Amazon.com;

“Marriage, Sex and Death: The Family and the Fall of the Roman West” by Emma Southon (2017) Amazon.com;

“Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian”

by Susan Treggiari (1991) Amazon.com;

“Marriage, Divorce, and Children in Ancient Rome” by Beryl Rawson (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Discourse of Marriage in the Greco-Roman World” by Jeffrey Beneker and Georgia Tsouvala (2020) Amazon.com;

“Revisiting Rape in Antiquity: Sexualised Violence in Greek and Roman Worlds”

by Susan Deacy, José Malheiro Magalhães, et al. (2023) Amazon.com;

“Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome” by Thomas A. J. McGinn (2003) Amazon.com;

“Prostitutes and Matrons in the Roman World” by Anise K. Strong (2016) Amazon.com;

“Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Ancient World” by Christopher A. Faraone and Laura K. McClure (2006) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook (Bloomsbury) by Bonnie MacLachlan (2013) Amazon.com;

“A Rome of One's Own: The Forgotten Women of the Roman Empire” by Emma Southon (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman Homosexuality” by Craig A. Williams (2010) Amazon.com;

“Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents” by Thomas K. Hubbard (2003) Amazon.com;

“Female Homosexuality in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Sandra Boehringer (2021) Amazon.com;

Ancient Roman Ideas About Sex

Hope E. Ashby wrote: As in Greek culture, phallic symbolism continued to occupy a central role in religion and in other spheres of Roman culture. It was from Greek mythology and from Roman views of sex in opposition to death that Freud later was to refine many of his ideas concerning eros and thanatos and to take the name of King Oedipus to signify the sexual attraction between son and mother. [Source: Hope E. Ashby, “Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia”, Haeberle, Erwin J., Bullough, Vern L. and Bonnie Bullough, eds.]

As was not the case in Greek custom, Roman women were granted a good bit of independence as history progressed. Though virginity was valued, it was prized not for its own sake but for the practical reason that monogamous behavior was expected of married women. Roman men, by contrast, were accorded considerable sexual freedom. Men did not have to be monogamous, but they were to avoid involvement with other men's wives. Prostitution was accepted among poorer Roman women. The sexual, including homosexuality, appears to have been accepted as natural in Roman life. A number of emperors were homosexual or bisexual in their life-styles. The excesses of Roman sexual life, especially of the later era, were decidedly at odds with the moderation and self-control so central to the values of earlier Greek culture.

Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “Graeco-Roman domestic sexuality rested on a triad: the wife, the concubine and the courtesan. The fourth century B.C. Athenian orator Apollodoros made it very clear in his speech Against Neaira quoted by Demosthenes that 'we have courtesans for pleasure, and concubines for the daily service of our bodies, but wives for the production of legitimate offspring and to have reliable guardians of our household property'. Whatever the reality of this domestic set-up in daily life in ancient Greece, this peculiar type of 'ménage à trois' pursued its course unhindered into the Roman period: monogamy de jure appears to have been very much a façade for polygamy de facto. [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3 ~]

Christianized Rome was not as tolerant about sex for sex sake as Republican and Imperial Rome. Dauphin wrote: “The advent of Christianity upset this delicate equilibrium. By forbidding married men to have concubines on pain of corporal punishment, canon law elaborated at Church councils took away from this triangular system one of its three components. Henceforth, there remained only the wife and the courtesan... Besides the sin of lust punished by illness with which prostitutes contaminated all those who approached them physically, harlots embodied also the sin of sexual pleasure amalgamated with that of non-procreative sex condemned by the Church Fathers. The Apostolic Constitutions (dated from A.D. 375 to 380) forbade all non-procreative genital acts, including anal sex and oral intercourse. The art displayed by prostitutes consisted precisely in making full use of sexual techniques which increased their clients' pleasure. Not surprisingly therefore, Lactantius (A.D. 240-320) condemned together sodomy, oral intercourse and prostitution (Divin. Inst. 5.9.17).” ~

Book: “Roman Sex: 100 B.C. to A.D. 250" by John R. Clarke (Harry N. Abrams, 2003).

Marital Sex in Ancient Rome

Describing a Roman wedding night, social historian Paul Veyne wrote: "The wedding night took the form of a legal rape from which the woman emerged “ ”offended with her husband” who, accustomed to using his slave women as he pleased, found it difficult to distinguish between raping a woman and taking the initiative in sexual relations. It was customary for the groom to forego deflowering his wife on the first night, out of concern for her timidity; but he made up for his forbearance by sodomizing her."

Jana Louise Smit wrote for Listverse: “Things in the Roman bedroom weren’t exactly even. While women were expected to produce sons, uphold chastity, and remain loyal to their husbands, married men were allowed to wander. He even had a rule book. It was fine to have extramarital sex with partners of both genders, but it had to be with slaves, prostitutes, or a concubine/mistress. Wives could do nothing about it since it was socially acceptable and even expected from a man. [Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, August 5, 2016]

“While undoubtedly there were married couples who used passion as an expression of affection for one another, the general unsympathetic view was that women tied the knot to have children and not to enjoy a great sex life. That was for the husband to savor, and some savored it a little too much—slaves had no rights over their own bodies, so the rape of a slave was not legally recognized.”

Birth Control and Contraceptives in the Greco-Roman World

dates were consumed to avoid pregnancy

There is some evidence that the Romans used oiled animal bladders as condom-like sheaths. Roman women were told sperm could be expelled by coughing, jumping and sneezing after intercourse, and repeated abortions produced sterility.

Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “One technique perfected by prostitutes both increased the pleasure of their partners and was contraceptive. Lucretius (99-55 B.C.)' description of prostitutes twisting themselves during coitus was echoed by the Babylonian Talmud: 'Rabbi Yose is of the opinion that a woman who prostitutes herself turns round to prevent conception'... [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3 ~]

In the sermons of the Church Fathers, contraception and prostitution formed a couple that could only engender death. St John Chrysostom (died A.D. 407) cried out in Homily 24 on the Epistle to the Romans 4: 'For you, a courtesan is not only a courtesan; you also make her into a murderess. Can you not see the link: after drunkenness, fornication; after fornication, adultery; after adultery, murder?'.

See Separate Article: POPULATION, CENSUSES AND BIRTH CONTROL IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Aphrodisiacs in Ancient Rome

The Romans and Greeks regarded garlic and leeks as aphrodisiacs. Truffles, artichokes and oysters were also associated with sexuality. Anise-tasting fennel was popular with Greeks who thought it made a man strong. The Romans thought it improved eyesight.

Liquamen, a sauce was made from rotting fish guts, vinegar, oil, and pepper, was said to be an aphrodisiac. Variants of the sauce were used on fish and fowl as far back as 300 B.C. Among the recipes discovered at Pompeii were mushrooms with honey-and-liquamen sauce, soft-boiled eggs with pine kernels and liquamen sauce, and venison with caraway seeds, honey and liquamen sauce.

Mark Oliver wrote for Listverse: “The gladiators who lost became medicine for epileptics while the winners became aphrodisiacs. In Roman times, soap was hard to come by, so athletes cleaned themselves by covering their bodies in oil and scraping the dead skin cells off with a tool called a strigil. “Usually, the dead skin cells were just discarded—but not if you were a gladiator. Their sweat and skin scrapings were put into a bottle and sold to women as an aphrodisiac. Often, this was worked into a facial cream. Women would rub the cream all over their faces, hoping the dead skin cells of a gladiator would make them irresistible to men.”[Source: Mark Oliver, Listverse, August 23, 2016]

Erotic Writers in Antiquity

Hope E. Ashby wrote: In Roman literature, Ovid's Art of Love was a guide to those who wished to evoke the sexual passions of the objects of their desire. Ovid, along with other Roman writers such as Virgil, viewed sex and love with a cynical eye and saw women as seductive and manipulative. Roman literature later influenced the work of English writers, including the comedies of William Shakespeare.[Source: Hope E. Ashby, “Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia”, Haeberle, Erwin J., Bullough, Vern L. and Bonnie Bullough, eds.]

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: “Elephantis was a licentious Greek poetess who wrote on the different modes of coition. In her work (which has perished) it is supposed that she enumerated nine postures of venery. Astyanassa, the maid of Helen of Troy, was, according to Suidas, the first writer on erotic postures, and Philaenis and Elephantis (both Greek maidens) followed up the subject. Aeschrion however ascribes the work attributed to Philaenis to Polycrates, the Athenian sophist, who, it is said, placed the name of Philaenis on his volume for the purpose of blasting her reputation. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

“This subject occupied the pens of many Greek and Latin authors, amongst whom may be mentioned: Aedituus, an erotic poet noticed by Apuleius in his Apology: Annianus (in Ausonius); Anser, an erotic poet cited by Ovid; Aristides, the Milesian poet; Astyanassa, above mentioned; Bassus; Callistrate, a Lesbian poetess, noted for obscene verses; Cicero, in his amorous letters to Cerellia; Cinna (Helvius), a Latin amatory poet; Cyrene, the artist of amatory tabellae or ex-votos offered to Priapus, and who enumerated twelve postures; Elephantis, the writer on Varia concubitis genera, above mentioned; Eubius, the doubtful author of a work on Pleasure; Everemus, a Messenian writer, whose works were translated into Latin by Ennius; Hemitheon of Sybaris, author of the Sybaritic books cited by Martial and Lucian for their lubricity. Hortensius, a lascivious writer; Laevius, who composed the poem Io, and wrote several books on love bearing the title of Erotopaegnia; Memmius, of whom Pliny the Younger speaks; Mimnermus, a Smyrnian erotic poet who flourished about the time of Solon; Musaeus; Myonia, an Aelian author; Naevius, a licentious poet; Nico, a Samian maiden, said by Xenophon to be the writer of lewd books.”

Others include: “Paxamus, who wrote the Dodecatechnon, a volume treating of twelve erotic postures; Philaenis, cited above; Pliny the Younger, whose amatory work is not extant, but which he mentions in his letters; Proculus, the writer of amorous elegies; Protagorides, Amatory Conversations, Sabellus, contemporary with Martial, whose poem on the various modes of congress is lost; Sappho, the celebrated Greek poetess, equally renowned as the queen of tribades; Sisenna, who translated the works of Aristides into Latin; Sotades, the Mantinean poet; Sphodrias, who composed an Art of Love; Sulpitia, an erotic, but modest, poetess, who wrote on conjugal love; Sulpitius (Servius), an author of amatory songs; Ticida; and Trepsicles, Amatory Pleasures. Sotades was the first to treat of Greek love or dishonest and unnatural love. He wrote in the Ionian dialect and according to Suidas he was the author of a poem entitled Cinaedica.

Erotic Art in Ancient Rome

Much of what we know about sex in the Roman era is based on images that have been found in brothels and villas, various objects of art, and erotic ceramic medallions from Gaul. Erotic ceramic medallions from Gaul show sex scenes with captions incised directly into the clay. One that shows a soldier making love with woman and crowning her with laurel wreath reads: “You alone conquer me."

Brothel pictures depicted couples in flagrante and with , apostrophic penises. In Ashkelon in present-day Israel archaeologists found scores of palm-size ceramic oil lamps with mythical and sexual themes in a villa in wealthy part of town. Because the lamps had not been lit it is thought they were part of collection.

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: “The Roman voluptuaries were accustomed to ornament their chambers with licentious paintings, the subjects of which were chiefly taken from the works of Philaenis,Elephantis and other erotic writers. Thus Lalage lays a series of tablets, representing different postures in copulation, as ex-votos on the altar of Priapus. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

fresco from a Pompeii ristorante

“Propertius censures the custom of hanging these obscene pictures on the walls of rooms. Suetonius says of Tiberius, 'He had several chambers set round with pictures and statues in the most lascivious attitudes, and furnished with the books of Elephantis, that none might lack a pattern for the execution of any lewd project that was prescribed him.' Ovid writes, 'They join in venery in a thousand forms; no tablet could suggest more modes.' And Apuleius, 'And, having imitated in their every mode the joyous tablets, let her change posture, and herself hang o'er me on the couch.”

David Silverman of Reed College asked his students to ponder these questions: “What does the evidence about the Roman predilection for erotic paintings tell us about Roman sexuality? Evidence here includes not only the preserved paintings themselves, but also their locations and intended viewers, as well as what contemporary writers had to say about them. Where were these paintings? Were they only for men to see, or only for men and female prostitutes, or for married women as well? Was the purpose of the paintings to kindle sexual desire? To function as erotodidaxis, instructional media? Or something else? For the Romans, what made the distinction between the erotic and the obscene? [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Erotic Art in Pompeii and Herculaneum

The first archaeologists to excavate Pompeii were surprised by some of the obscene things they found and hid them from public view. Mark Oliver wrote for Listverse: “ “Pompeii was filled with art that was so filthy that it was locked in a secret room for hundreds of years before anyone was allowed to look at it. The town was full of the craziest erotic artwork you’ll ever see—for example, the statue of Pan sexually assaulting a goat. On top of that, the town was filled with prostitutes, which gave even the street tiles their own special little touch of obscenity. To this day, you can walk through Pompeii and see a sight Romans would enjoy every day—a penis carved into the road with the tip pointing the way to the nearest brothel.” [Source: Mark Oliver, Listverse, August 23, 2016]

Steve Coates wrote in the New York Times, “Much of the art” in Pompeii is “highly eroticized, even when not bluntly pornographic. Much else can striker the modern viewer as bizarre — something out of Petronius or Apuleius rather than Cicero or Horace — like a fresco of the judgment of Solomon story enacted by pygmies."

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Some of the gardens of houses in Pompeii were decorated with bronze tintinnabula (wind chimes) sculpted in the form of the penis. Sexual imagery was so prevalent in Pompeii that sexually explicit art and objects were kept — at the instructions of Francis I, king of Naples — in a special “Secret Cabinet” (Gabinetto Segreto) at the Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. But it wasn’t just Pompeii (which has a reputation for sexually licentious behaviour because so much of its artwork was preserved). To name just a few examples: wine cups often depict what we might call ‘pornographic scenes’; the deity Priapus is always shown with an oversized penis; and a statue of Pan engaged in sexual congress with a goat (to be fair to Pan he was half-goat himself) was found in the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 22, 2018]

Mooning and Syphilis in Ancient Rome

Mark Oliver wrote for Listverse: “Rome holds the unique distinction of recording the first mooning in history”. According to Josephus: During Passover, Roman soldiers were sent to stand outside of Jerusalem to keep watch in case the people revolted. They were meant to keep the peace, but one soldier did a little bit more: he lifted “up the back of his garments, turned his face away, and with his bottom to them, crouched in a shameless way and released at them a foul-smelling sound where they were offering sacrifice.” The Jews were furious. First, they demanded that the soldier be punished, and then they started hurtling rocks at the Roman soldiers. Soon a full-on riot broke out in Jerusalem—and a gesture that would live on for thousands of years was born. [Source: Mark Oliver, Listverse, August 23, 2016]

Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “According to the Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 33a), Rabbi Hoshaia of Caesarea also threatened with syphilis 'he who fornicates'. He will get 'mucous and syphilous wounds' and moreover will catch the hydrocon - an acute swelling of the penis. These are precisely the symptoms of the primary phase of venereal syphilis. [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3 ~]

“There are, of course, two conflicting theories concerning syphilis. According to the Colombian or American theory, syphilis (Treponema pallidum) appeared for the first time in Barcelona in 1493, brought back from the West Indies by the sailors who had accompanied Christopher Columbus. On the other hand, the unicist theory claims that the pale treponema has existed since prehistoric times and has spread under four different guises: pinta on the American continent, pian in Africa, bejel in the Sahel, and lastly venereal syphilis which is the final form of a treponema with an impressive gift for mutation and adaptation. ~

“The latter hypothesis is supported by a recent discovery of great importance made by the Laboratoire d'anthropologie et de préhistoire des pays de la Méditerranée occidentale of the CNRS at Aix-en-Provence. Lesions characteristic of syphilis have been detected on a foetus gestating in a pregnant woman who had been buried between the third and the fifth centuries A.D. in the necropolis of Costobelle in the Var district. Bejel is still endemic amongst some peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean. A few cases have been recorded archaeologically on skeletons of Bedouins and settled Arabs of Ottoman Palestine. Contracted in childhood, bejel spreads by physical but not necessarily sexual contact, whereas syphilis which is an illness of adults, is transmitted only sexually. In both cases, the deterioration of the bones as well as the symptoms and the progress of the illness are identical. However, only venereal syphilis is able to go through the placenta and to infect the embryo. The mother of the Costobelle foetus must therefore have suffered from venereal syphilis. This would confirm the view held by modern pathologists that venereal syphilis already existed in Ancient Greece and Rome. ~

Did Erotic, Roman-Era Spanish Dancing Girls Do the Fandango?

Juvenal wrote in in Satire 11: “You may look perhaps for a troop of Spanish maidens to win applause by immodest dance and song, sinking down with quivering thighs to the floor — such sights as brides behold seated beside their husbands, though it were a shame to speak of such things in their presence. . . . My humble home has no place for follies such as these. The clatter of castanets, words too foul for the strumpet that stands naked in a reeking archway, with all the arts and language of lust, may be left to him who spits wine upon floors of Lacedaemonian marble; such men we pardon because of their high station. In men of moderate position gaming and adultery are shameful; but when those others do these same things, they are called gay fellows and fine gentlemen. My feast to-day will provide other performances than these. The bard of the Iliad will be sung, and the lays of the lofty-toned Maro that contest the palm with his. What matters it with what voice strains like these are read?

“Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: “Gifford, commenting on the passage in Juvenal, remarks that the dance alluded to is neither more nor less than the Fandango, which still forms the delight of all ranks in Spain, and which, though somewhat chastised in the neighbourhood of the capital, exhibits at this day, in the remote provinces, a perfect counterpart (actors and spectators) of the too free but faithful representation before us. In a subsequent line, Juvenal mentions the testarum crepitus, the clicking of the castanets, which accompanies this dance. The testae were small oblong pieces of polished wood or bone which the dancers held between their fingers and clashed in measure, with inconceivable agility and address. The Spaniards of the present day are very curious in the choice of their castanets; some have been shown to me that cost five-and-twenty or thirty dollars a pair; these were made of the beautifully variegated woods of South America. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

muses

“Pollux notes, 'The ekláktismata were dances for women: they had to throw their feet higher than their shoulders.' This kind of dance is not unknown in more modern times. J. C. Scaliger writes, 'Still, nowadays, the Spaniards touch the occiput and other parts of the body with their feet.' Bulenger mentions the Bactriasmus, a lascivious dance, with undulations of the loins.

“Julius Caesar Scaliger says, 'One of the infamous dances was the díknpma or díknoûothai, meaning wriggling the haunches and thighs, the crissare of the Romans. In Spain this abominable practice is still performed in public.' Martial also states that these dances were sometimes accompanied by the cymbal — 'For my page wantons with Lampsacian [Priapeian] verse, and strikes the cymbal with the hand of a Spanish dancer.' Again he speaks of the wanton dancers from Cadiz who were skilled in the art of licentiously undulating their loins; and of Telethusa's lascivious gestures and agile posturing in the Gaditanian fashion to the sound of the castanets.1 Vergil also alludes to this kind of dancing with castanets. The Thesaurus Eroticus, under 'comessationes', describes them as naked dancing-girls who with tremulous loins and obscene movements provoked the lust of their spectators, whilst the tractatrices were softly kneading and pressing the limbs of their masters and soliciting an erection with their apt touches. Martial and Juvenal make copious reference to this subject. These tractatrices were female slaves whose business was to knead and make supple by manual pressure all the joints of their master's body after his bath. The effeminate refinement of the Roman voluptuaries is well shown by the fist of attendants given in the Erotika Biblion, which includes as 'toilet accessories' jatraliptae (youths who wiped the bather with swansdown); unctares (perfumers); fricatores (rubbers); fractatrices (massage-girls); dropacistae (corn extractors); alipilarii (those who plucked the hair from the armpits and other parts of the body); paratiltriae (children entrusted with the cleansing of all the orifices of the body, the ears, anus, vulva, &c.); :and picatrices (young girls who attended to the symmetrical arrangement of the pubic hair). [1. Joan Baptista Suarez de Salazar mentions the fashion amongst the Roman nobles of obtaining harlots from Cadiz for their guests' entertainment.]

Inscriptions from Pompeii About Love and Sex

William Stearns Davis wrote: “There are almost no literary remains from Antiquity possessing greater human interest than these inscriptions scratched on the walls of Pompeii (destroyed 79 A.D.). Their character is extremely varied, and they illustrate in a keen and vital way the life of a busy, luxurious, and, withal, tolerably typical, city of some 25,000 inhabitants in the days of the Flavian Caesars. Most of these inscriptions carry their own message with little need of a commentary. Perhaps those of the greatest importance are the ones relating to local politics. It is very evident that the so-called "monarchy" of the Emperors had not involved the destruction of political life, at least in the provincial towns. [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 260-265]

1) “Here slept Vibius Restitutus all by himself his heart filled with longings for his Urbana.” 2) “He who has never been in love can be no gentleman.” 3) “Health to you, Victoria, and wherever you are may you sneeze sweetly.”

4) “Restitutus has many times deceived many girls.” 5) “Romula keep tryst here with Staphylus.” 6) “If any man seek /My girl from me to turn, /On far-off mountains bleak, /May Love the scoundrel burn! 7) “If you a man would be, /If you know what love can do, /Have pity and suffer me /With welcome to come to you.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024