BATHS IN ANCIENT ROME

In ancient Rome, thermae were facilities for bathing. The term usually refers to large imperial bath complexes, with balneae refering to smaller-scale facilities. There were public and private thermae and they existed in great numbers throughout Rome. Most Roman cities had at least one and many urban areas had many of them. They were centers not only for bathing, but also socializing and relaxing as well. Bathhouses could also be found at wealthy private villas, town houses, and forts.

Roman public baths had a pubic sanitation system with water piped in and piped out. They were supplied with water from an adjacent river or stream, or within cities by aqueduct. The water would be heated by fire then channelled into different parts of the bath. The architecture of baths is discussed by Vitruvius in "De architectura." Baths at home were generally only big enough to sit up in and they were filled with water from pottery buckets by slaves. Baths proliferated all over the Roman Empire for both military and civilian use. Many were quite ornate, with huge colonnades, decorative mosaics and pools with different temperature water.

On the Forum Baths at Pompeii which appear to have been built soon after Pompeii became a Roman colony, Dr Joanne Berry wrote for the BBC: “ There are separate areas for men and women, the men's baths being far more elaborate and spacious. Thanks to under-floor heating, and air ducts built into the walls, the whole room would have been full of steam when in use. Grooves in the ceiling allowed condensation to be channelled to the walls, rather than drip onto bathers. Cold water was piped into the basin, thus enabling bathers to cool off when they wanted.” [Source: Dr Joanne Berry, Pompeii Images, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

RELATED ARTICLES:

BATHING IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BEAUTY AND COSMETICS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

HYGIENE AND BODY FUNCTIONS IN ANCIENT ROME: CLEANLINESS, PERFUME, FARTS AND PEE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TOILETS IN ANCIENT ROME: DISGUSTING PUBLIC ONES, CHAMBER POTS AND TAXES europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Essential Roman Baths” by Stephen Bird (2007) Amazon.com;

“Bathing in Public in the Roman World” by Garret Fagan.(1999) Amazon.com;

"Roman Bath” by Peter Davebport (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Story of Roman Bath” by Patricia Southern (2013) Amazon.com;

“Roman Baths” by Barry Cunliffe (1980) Amazon.com;

“Bathing in the Roman World” by Fikret Yegül Amazon.com;

“A Cultural History of Bathing in Late Antiquity and Early Byzantium”

Amazon.com;

“Baths of Caracalla: Guide” by Gail Swirling (2008) Amazon.com;

“Decoration and Display in Rome's Imperial Thermae: Messages of Power and their Popular Reception at the Baths of Caracalla” by Maryl B. Gensheimer (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Baths of Caracalla” by Piranomonte Marina Amazon.com;

“The Baths of Caracalla: A Study in the Design, Construction, and Economics of Large-Scale Building Projects in Imperial Rome” by Janet Delaine (1997)

Amazon.com;

“Cosmetics & Perfumes in the Roman World” by Susan Stewart (2007) Amazon.com;

“Hygiene, Volume I: Books 1–4" (Loeb Classical Library) by Galen and Ian Johnston Amazon.com;

“Hygiene, Volume II: Books 5–6. Thrasybulus. On Exercise with a Small Ball (Loeb Classical Library) by Galen and Ian Johnston Amazon.com;

“Pearls and Petals Beauty Rituals in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Oriental Publishing Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Sanitation in Roman Italy: Toilets, Sewers, and Water Systems”

by Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow (2018) Amazon.com;

“Public Toilets (Foricae) and Sanitation in the Ancient Roman World: Case Studies in Greece and North Africa” by Antonella Patricia Merletto (2023) Amazon.com;

“Latrinae et Foricae: Toilets in the Roman World”, Illustrated, by Barry Hobson (2009) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

History of Baths in Ancient Rome

Rome was famous for its public baths, which were first developed around the 2nd century B.C. from small bathhouses that served as gathering places like a local pub. In 25 B.C., Agrippa, a chief deputy under Augustus, designed and built the first thermae, a large bath with extensive facilities. Emperors that followed commissioned increasingly large thermae.

Caracalla

Since the middle of the third century B,C. wealthy Romans had built bathing halls in their town houses and country villas. But this luxury was for the very rich and the republican austerity which forbade Cato the Censor to take a bath in the presence of his son prevented the building of baths outside the family domain. In the long run, however, the love of cleanliness triumphed over false pruderies. In the course of the second century B.C. public baths the men's and women's separate, of course, unlike later times made their appearance in Rome; the feminine plural balneae denoting the public, as opposed to the neuter balneum, or private, bath. Philanthropists endowed baths in their quarter of the city. Contractors built others as a speculation and charged entrance fees. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

In 33 B.C. Agrippa had a census of baths taken; there were 170 and the number grew steadily as time went on. Pliny the Elder gave up trying to count those of his time, and later they approached a thousand. The fee charged by the owner or by the operator to whom he had leased the place was microscopic: a quadrant, quarter of an as, or roughly half a cent and children entered free. In 33 B.C. Agrippa was aedile and one of his duties was to supervise the public baths, test their heating apparatus, and see to their cleaning and policing. In order to mark his term of office by a sensational act of generosity he undertook to pay all entrance fees for the year of his aedileship. Not long after, he founded the thermae which bear his name, and these were to be free in perpetuity. This was a revolutionary principle in keeping with the paternal role which the empire had assumed toward the masses. It brought with it a revolution both in architecture and in manners; and buildings modelled on Agrippa's grew ever larger with succeeding reigns.

After the baths of Agrippa, the thermae of Nero were erected on the Campus Martius. Then Titus built his beside the ancient Domus Aurea, with an external portico facing the Colosseum. The brick cores of several columns of this portico are standing to this day. Next Trajan built on the Aventine the thermae which he dedicated to the memory of his friend Licinius Sura; and to the north-west of those of Titus, on the site of part of the Golden House which had been destroyed by fire in 104, he erected others to which he gave his own name and which he was able to inaugurate on the same day as his aqueduct. Later there came the thermae which we call the baths of Caracalla, but which ought to be known by their official designation of "Thermae of Antoninus," for while Septimius Severus laid the foundations in 206, and they were prematurely inaugurated by his son Antoninus Caracalla, they were completed by the last Antonine of the dynasty, Severus Alexander, between 222 and 235.

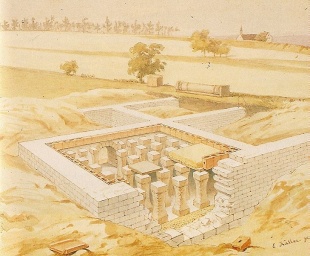

The ruins of the baths of Diocletian today house the National Roman Museum, the Church of Saint Mary of the Angels, and the Oratory of Saint Bernard; and the plan of their giant exedra can be traced by the curves of the piazza, which preserves the name. Last of all, in the fourth century the thermae of Constantine were built on the Quirinal. The best preserved of these great baths are those of Diocletian, covering an area of thirteen hectares, and those of Caracalla, spreading over eleven hectares, both of which belong to the wonders of ancient Rome. These grandiose, bare ruins impress even the most insensitive tourist. Both, however, lie outside the limits of the chronological framework within which we are striving to keep our attention. -But the ruins of the baths of Trajan have within the last few years been sufficiently excavated to allow us to follow the master lines of their plan and establish the fact that it corresponds to the plan of the baths of Caracalla. There is only a difference of scale between the two. It is comparatively simple, therefore, to divine the typical arrangement of these monumental buildings in the day when Martial grew enthusiastic over them, and take stock of the innovations they had introduced.

Parts of a Roman Bath

Most baths had the same essential elements: a changing room, a tepidarium (a sweating room and warm-water bathing hall), caldarium (hot-water bathing hall), laconicum ( super hot-water bathing hall), frigidarium (cold-water bathing hall), a large open hall, and an open-topped rotunda (with warm circulating air around it). Water was supplied to the baths through networks of underground pipes.

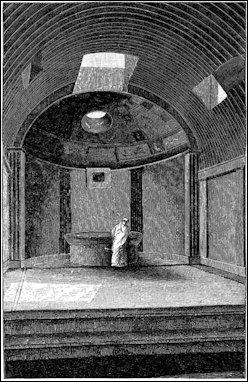

Tepidarium of the Old Baths at Pompeii The ruins of the public and private baths found all over the Roman world, together with an account of baths by Vitruvius, and countless allusions in literature, make very clear the general construction and arrangement of the bath, but show that the widest freedom was allowed in matters of detail. For the luxurious bath of classical times four things were thought necessary: a warm anteroom, a hot bath, a cold bath, and the rubbing and anointing with oil. All these might have been provided in one room, as all but the last are furnished in every modern bathroom, but as a matter of fact we find at least three rooms set apart for the bath in very modest private houses, and often five or six, while in the public establishments this number might be multiplied several times. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“In the better equipped baths were provided: (1) a room for undressing and dressing (apodyterium), usually unheated, but furnished with benches and often with compartments for the clothes; (2) the warm anteroom (tepidarium), in which the bather waited long enough for the perspiration to start, in order to guard against the danger of passing too suddenly into the high temperature of the next room (caldarium); (3) the hot room (caldarium) for the hot bath; (4) the cold room (frigidarium) for the cold bath; (5) the room for the rubbing and anointing with oil that finished the bath (unctorium), from which the bather returned into the apodyterium for his clothes. |+|

“In the more modest baths space was saved by using one room for several purposes. The separate apodyterium might be dispensed with, as the bather could undress and dress in either the frigidarium or tepidarium according to the weather; or the unctorium might be dispensed with by using the tepidarium for this purpose as well as for its own. In this way the suite of five rooms might be reduced to four or three. On the other hand, private baths had sometimes an additional hot room without water (laconicum), used for a sweat bath, and a public bathhouse would be almost sure to have an exercise ground (palaestra) with a pool at one side (piscina) for a cold plunge and a room adjacent (destrictarium) in which the sweat and dirt of exercise were scraped off with the strigilis before and after the bath. It must not be supposed that all bathers went the round of all the rooms in the order given above, though that was common enough. Some dispensed with the hot bath altogether, taking instead a sweat in the laconicum, or if that was lacking, in the caldarium, removing the perspiration with the strigil (strigilis), following this with a cold bath (perhaps merely a shower or douche) in the frigidarium and the rubbing with linen cloths and anointing with oil. Young men who deserted the Campus and the Tiber for the palaestra and the bath would content themselves with removing the effects of their exercise with the scraper, taking a plunge in the open pool, and then a second scraping and the oil. Much would depend on the time and the tastes of individuals. Physicians, too, laid down strict rules for their patients to follow.” |+|

Like most Roman cities of its day,Plotinopolis in Thrace in modern-day Greece had a public bath structure. Archaeology magazine reportedly: Digging where he believes the baths were located, archaeologist Matthew Koutsoumanis unearthed large and well-preserved mosaic that once covered the bath building's floors. As of 2012, 104 square feet of mosaics had been uncovered, which Koutsoumanis believes is about one quarter of the entire floor surface. The mosaics, which date to the second half of the second or the early-third century A.D., show various scenes from Greek mythology, including the stories of Leda and the swan and the labors of Hercules, as well as a great variety of intricate multicolored geometric patterns. [Source: Archaeology magazine, 2, March-April 2012]

Layout of Ancient Roman Baths

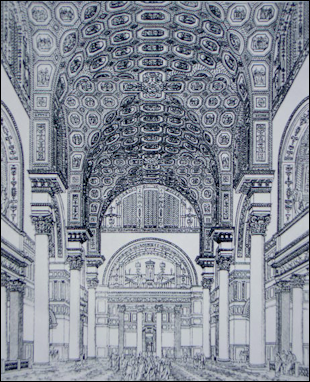

At a typical thermae was a hot, cold, and hot-air baths, and sometimes swimming baths, and tub baths. Externally the enormous quadrilateral was flanked by porticos full of shops and crowded with shopkeepers and their customers; inside it enclosed gardens and promenades, stadia and rest rooms, gymnasiums and rooms for massage, even libraries and museums. The baths in fact offered the Romans a microcosm of many of the things that make life attractive. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

In the center of the thermae rose the buildings of the baths proper. None of the balneae could rival them, either in the volume of water led from aqueducts into their reservoirs, which in the baths of Caracalla occupied two-thirds of the south side with their sixty-four vaulted chambers; or in the complex precision of their system of furnaces, of hypocauses and hypocausta, which conveyed, distributed, and tempered the warmth of the halls.

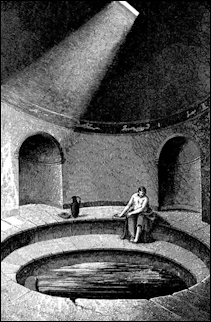

Near the entrance were the dressing-rooms where the bathers came to undress (the apodyteria). Next came the tepidarium, a large vaulted hall that was -only gently warmed, which intervened between the frigidarium on the north and the caldarium on the south. The frigidarium, which was probably too big to be completely roofed in, contained the pool into which the bathers plunged. The caldarium was a rotunda lit by the sun at noon and in the afternoon, and heated by vapour circulating between the suspensurae laid beneath its pavement. It was surrounded by little bathing boxes where people could bathe in private; and a giant bronze basin of water in the center was kept at the required temperature by the furnace immediately below in the middle of the hypocausis that underlay the entire hall. To the south of the caldarium lay the sudatoria, or laconica, whose high temperature induced a perspiration like the hot room of a Turkish bath. Finally the whole gigantic layout was flanked by palaestrae, themselves backing on recreation rooms, where the naked bathers could indulge in their favorite forms of exercise.

This was not all: this imposing group of buildings was surrounded by an esplanade, cooled by shade and playing fountains, which gave space for playing grounds and was enclosed by a continuous covered promenade (the xystus). Behind the xystus curved the exedrae of the gymnasiums and the sitting-rooms, the libraries, and the exhibition halls. This was the truly original feature of the thermae. Here the alliance between physical culture and intellectual curiosity became thoroughly Romanised. Here it overcame the prejudice which the importation of sports in the Greek style had aroused. No doubt conservative opinion continued to look askance at athletics, as encouraging immorality by exhibitionism and diverting its devotees from the virile and serious apprenticeship required by the art of war, teaching them to think more of exciting admiration for their beauty than of developing the qualities of a good foot soldier. But opinion presently ceased to be offended at nudism in the baths, where it was obligatory, and admitted almost all athletic games to equal honor, as long as they were not practiced as a spectacle, but for their own sake and served the same salutary purpose as the baths themselves. Games prefaced and reinforced the tonic effect of the baths on bodily health and fitness.

Heating a Roman Bath

Hot water was piped into the baths in Pompeii and many other baths. Some historians has suggested that in the days before chlorination public baths were probably filthy. Adam Hart-Davis wrote for the BBC: At Bath in western England, “you can still see a lead pipe that seems to have carried water under pressure to a sort of whirlpool bath. The word plumbing comes from the Latin word plumbum, meaning lead.” [Source: Adam Hart-Davis, BBC, February 17, 2011]

The arrangement of the rooms, were they many or few, depended upon the method of heating. This in early times must have been by stoves placed in the rooms as needed, but by the end of the Republic the furnace had come into use, heating the rooms as well as the water with a single fire. The hot air from the furnace was not conducted into the rooms directly, as it is with us, but was made to circulate under the floors and through spaces around the walls, the temperature of the room depending upon its proximity to the furnace. The laconicum, if there was one, was put directly over the furnace, next to it came the caldarium and then the tepidarium; the frigidarium and the apodyterium, having no need of heat, were at the greatest distance from the fire and without connection with it. . [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“If there should be two sets of baths in the same building, as there sometimes were for the accommodation of men and women at the same time, the two caldaria were put on opposite sides of the furnace and the other rooms were connected with them in the regular order; the two entrances were at the greatest distance apart. The method of conducting the air under the floors is shown. There were really two floors; the first was even with the top of the firepot, the second (suspensura) with the top of the furnace. Between them was a space of about two feet into which the hot air passed.11 On the top of the furnace, just above the level, therefore, of the second floor, were two kettles for heating the water. One was placed well back, where the fire was not so hot, and contained water that was kept merely warm; the other was placed directly over the fire and the water in it, received from the former, was easily kept intensely hot. Near them was a third kettle containing cold water. From these three kettles the water was piped as needed to the various rooms. |+|

Caldariums and Frigidariums

Frigidarium at Pompeii Caldarium: The hot-water bath was taken in the caldarium (cella caldaria), which served also as a sweat bath when there was no laconicum. It was a rectangular room. In the public baths its length exceeded its width; Vitruvius says the proportion should be 3:2. One end was rounded off like an apse or bay window. At the other end stood the large hot-water tank (alveus), in which the bath was taken by a number of persons at a time. The alveus was built up two steps from the floor of the room, its length equal to the width of the room and its breadth at the top not less than six feet. At the bottom it was not nearly so wide; the back sloped inward, so that the bathers could recline against it, and the front had a long broad step, for convenience of descent into it, upon which, too, the bathers sat. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

The water was received hot from the furnace, and was kept hot by a metal heater (testudo), which opened into the alveus and extended beneath the floor into the hot-air chamber. Near the top of the tank was an overflow pipe, and in the bottom was an escape pipe which allowed the water to be emptied on the floor of the caldarium, to be used for scrubbing it. In the apse-like end of the room was a tank or large basin of metal (labrum, solium), which seems to have contained cool water for the douche. In private baths the room was usually rectangular, and then the labrum was placed in a corner. For the accommodation of those using the room for the sweat bath only, there were benches along the wall. The air in the caldarium would, of course, be very moist, while that of the laconicum would be perfectly dry, so that the effect would not be precisely the same. |+|

Frigidarium and the Unctorium: The frigidarium (cella frigidaria) contained merely the cold plunge bath, unless it was made to do duty for the apodyterium, when there would be lockers on the walls for the clothes (at least in a public bath) and benches for the slaves who watched them. Persons who found the bath too cold would resort instead to the open swimming pool in the palaestra, which would be warmed by the sun. In one of the public baths at Pompeii a cold bath seems to have been introduced into the tepidarium, for the benefit, probably, of invalids who found even the palaestra too cool for comfort. The final process, that of scraping, rubbing, and oiling, was exceedingly important. The bather was often treated twice, before the warm bath and after the cold bath; the first might be omitted, but the second never. The special room, unctorium, was furnished with benches and couches. The scrapers and oils were brought by the bathers; they were usually carried along with the towels for the bath by a slave (capsarius). The bather might scrape (destringere) and oil (deungere) himself, or he might receive a regular massage at the hands of a trained slave. It is probable that in the large baths expert operators could be hired but we have no direct testimony on the subject. When there was no special unctorium, the tepidarium or apodyterium was made to serve instead. |+|

Private Bathhouse Versus Public Baths

A Private Bathhouse. The ruins of a private bath were found in Caerwent, Monmouthshire, England in 1855. The bath dates from about the time of Constantine (306-333 A.D.), and, small though it is, gives a clear notion of the arrangement of the rooms. The entrance (A) leads into the frigidarium (B), 10'6" x 6'6" in size, with a plunge (C), 10'6" x 3'3". Off B is the apodyterium (D), 10'6 x 13'3", which has the apse-like end that the caldarium ought to have. Next is the tepidarium (E), 12' x 12', which, contrary to all the rules, is the largest instead of the smallest of the four main rooms. Then comes the caldarium (F), 12' x 7'6", with its alveus (G), 6' x 3' x 2', but with no sign of its labrum left, perhaps because the basin was too small to require any special foundation. Finally comes the rare laconicum (H), 8' x 4', built over one end of the furnace (I), which was in the basement room (KK). The hot air passed as indicated by the arrows, escaping through openings near the roof in the outside walls of the apodyterium. It should be noticed that there was no direct passage from the caldarium (F) to the frigidarium (B), no special entrance to the laconicum (H), and that the tepidarium (E) must have served as the unctorium. The dimensions of the Caerwent bath as a whole are 31 x 34 feet. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Caldarium at Pompeii “The Public Baths. To the simpler bathhouse of the earlier times as well as to the bath itself was given the name balneum (balineum), used often by the dactylic poets in the plural, balnea, for metrical convenience. The more complex establishments of later times were called balneae, and to the very largest, which had features derived from the Greek gymnasia, the name thermae was finally given. These words, however, were loosely used and often interchanged in practice. Public baths are first heard of after the Second Punic War. They increased in number rapidly; 170 at least were operated in Rome in the year 33 B.C., and later there were more than eight hundred. With equal rapidity they spread through Italy and the provinces;12 all the towns and even many villages had at least one. They were public only in the sense of being open to all citizens who could pay the modest fee demanded for their use. Free baths did not exist, except when some magistrate or public-spirited citizen or candidate for office arranged to relieve the people of the fees for a definite time by meeting the charges himself. So Agrippa in the year 33 B.C. kept open free of charge 170 establishments at Rome. The rich sometimes in their wills provided free baths for the people, but always for a limited time. |+|

“Management. The first public baths were opened by individuals for speculative purposes. Others were built by wealthy men as gifts to their native towns, as such men give hospitals and libraries now; the administration was lodged with the town authorities, who kept the buildings in repair and the baths open by means of the fees collected. Other baths were built by the towns out of public funds, and others were credited to the later emperors. However they were started, the management was practically the same for all. They were leased for a definite time and for a fixed sum to a manager (conductor), who paid his expenses and made his profits out of the fees which he collected. The fee (balneaticum) was hardly more than nominal. The regular price at Rome for men seems to have been a quadrans, quarter of a cent; the bather furnished his own towels, oil, etc., as we have seen. Women paid more, perhaps twice as much, while children up to a certain age, unknown to us, paid nothing. Prices varied, of course, in different places. It is likely that higher prices were charged in some baths than in others in the same city, either because they were more luxuriously equipped or to make them more exclusive and fashionable than the rest, but we have no positive knowledge that this was done. |+|

Romans Baths for Men and Women

Archaeologists found a sign that read “Women" at one bath. Other baths had separate entrances, presumably for men and women. The so-called Stabian Baths at Pompeii give a correct idea of the smaller thermae and serves at the same time to illustrate the combination of baths for men and women under the same roof. In the plan the unnumbered rooms opening upon the surrounding streets were used for shops and stores independent of the baths; those opening within were for the use of the attendants or for purposes that cannot now be determined. The main entrance (1), on the south, opened upon the palaestra (2), which was inclosed on three sides by colonnades and on the west by a bowling alley (3), where large stone balls were found. Behind the bowling alley was the piscina (6) open to the sun, with a room on either side (5, 7) for douche baths and a destrictarium (4) for the use of the athletes. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Bath in Bath, England“There were two side entrances (8, 11) at the northwest, with the porter’s room (12) and manager’s office (10) within convenient reach. The room (9) at the head of the bowling alley was for the use of the players and may be compared with the similar room for the use of the gladiators. Behind the office was the latrina, marked 14. |+|

“On the east are the baths proper, the men’s to the south. There were two apodyteria (24, 25) for the men. Each had a separate waiting-room for the slaves (26, 27); (26) had a door to the street. Then come in order the frigidarium (22), the tepidarium (23), and the caldarium (21). The tepidarium, contrary to custom, had a cold bath. The main entrance to the women’s bath was at the northeast (17), but there was also an entrance from the northwest through the long corridor (15); both opened into the apodyterium (16). This contained in one corner a cold bath, as there was no separate frigidarium in the baths for women. Then come in the regular position the tepidarium (18) and caldarium (19). The furnace (20) was between the two caldaria, and the position of the three kettles which furnished the water is clearly shown. It should be noticed that there was no laconicum. It is possible that one of the two rooms marked 24 and 25 was used as an unctorium. The ruins show that the rooms were most artistically decorated, and there can be no doubt that they were luxuriously furnished. The colonnades and the large waiting-rooms gave ample space for the lounge after the bath, with his friends and acquaintances, which the Roman prized so highly. |+|

Large Roman Baths

The largest baths covered 25 or 30 acres and accommodated up to 3,000 people. Large city or imperial baths had swimming pools, gardens, concert hall, sleeping quarters, theaters, and libraries. Men rolled hoops, played handball and wrestled in the gymnasium. Some even had the equivalent of modern art galleries. Other baths had areas for shampooing, scenting, hair curling, manicure shops, perfumeries, garden shops, and rooms for discussing art and philosophy. Some of the greatest Roman sculptors such as the Lacoön group were found in ruined bathes. Brothels, with explicit pictures of the sexual services offered, were usually located near the baths.

The Baths of Caracalla (on a hill not far from the Circus Maximus in Rome) was the largest baths built by the Romans. Opened in A.D. 216 and covering 26 acres, more than six time the space in St. Paul's Cathedral in London, this massive marble and brick complex could accommodate 1,600 bathersand contained playing, fields, shops, offices, gardens, fountains, mosaics, changing rooms, exercise courts, a tepidarium (warm-water bathing hall), caldarium (hot-water bathing hall), frigidarium (cold-water bathing hall), and natatio (unheated swimming pool). Shelley wrote much of “Prometheus Bound” while sitting among the ruins at Caracalla.

Baths “operated on a large scale in all parts of Rome, in the smaller towns of Italy, and even in the provinces. They were often built where hot or mineral springs were found. These public establishments offered all sorts of baths, plain, plunge, douche, and with massage (Turkish); in many cases they offered features borrowed from the Greek gymnasia, exercise grounds, courts for various games, reading and conversation rooms, libraries, gymnastic apparatus, everything in fact that our athletic clubs now provide for their members. The accessories had become really of more importance than the bathing itself and justify the description of the bath under the head of amusements. In places where there were no public baths, or where they were at an inconvenient distance, the wealthy fitted up bathing places in their houses, but no matter how elaborate they were, the private baths were merely a makeshift at best. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

Baths of Diocletian

The first domes were built over public bathes. Finished in A.D. 305, the baths of Diocletian contained a high vaulted ceiling that was restored with the help of Michelangelo and later turned into a church.

The irregularity of plan and the waste of space in the Pompeian thermae just described are due to the fact that the baths were rebuilt at various times with all sorts of alterations and additions. Nothing can be more symmetrical than the thermae of the later emperors, as a type of which is the plan of the Baths of Diocletian, dedicated in 305 A.D. They lay in the northeastern part of the city and were the largest and, with the exception of those of Caracalla, the most magnificent of the Roman baths. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The plan shows the arrangement of the main rooms, all in the line of the minor axis of the building; the uncovered piscina (1), the apodyterium and frigidarium (2), combined as in the women’s baths at Pompeii, the tepidarium (3), and the caldarium (4), projecting beyond the other rooms for the sake of the sunshine. The uses of the surrounding halls and courts cannot now be determined, but it is clear from the plan that nothing known to the luxury of the time was omitted. In the sixteenth century Michelangelo restored the tepidarium as the Church of S. Maria degli Angeli, one of the largest in Rome. The cloisters that he built in the east part of the building are now a museum. One of the corner domed halls of the Baths is now a church and a number of other institutions occupy the site of part of the ruins. An idea of the magnificence of the central room, showing a restoration of the corresponding room in the Baths of Caracalla. |+|

Ancient Roman Spas

Romans were also one of the first people to credit mineral water with healing powers. The Greeks had known about mineral water but they considered it unhealthy. Romans drank and bathed in it and sought relief in mineral water for liver and kidney trouble and a host of other ailments. The Romans set up baths at natural hot springs in Baiae (near Pompeii) and Badoit and Vittel in what is now France. Julius Caesar bathed at Vichy. Later these were abandoned in favor of cold water resorts like Gabii near Rome.

The cold water bath of Chiancian Terme in Tuscany, known promoting "a healthy liver," consisted of various buildings arranged around a 60-x-130-foot swimming pool paved with roof tiles. At one end of the pool was a podium, presumable for a statue of a god or emperor. The pool was three-feet deep, adequate for bathing but not swimming, and was 64̊F.

Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology magazine: Around A.D. 60, at Aquae Sulis, the site of natural hot springs in what is now Bath, England, the Romans built a huge temple and spa complex that became a center for both pilgrimage and health. There, Romans and local Britons socialized and bathed, hoping to heal a host of ailments such as rheumatism, arthritis, and gout. They also worshipped the Romano-Celtic healing goddess Sulis Minerva. The Aquae Sulis springs had already been host to centuries — and possibly millennia — of ceremonies held by Bronze and Iron Age communities. Even after the destruction of the Roman baths in the sixth century A.D., Aquae Sulis’ legacy continued. The health-giving properties of the springs were well known in Britain throughout the Middle Ages, and by the seventeenth century, Bath was the place to see and be seen. It became common for visitors to drink the sulfurous thermal waters, a practice known as “taking the cure.” Some still engage in this activity, seeking its purported health benefits. [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2021

$2 Billion Roman Bathtub — the Vatican’s Most Valuable Pieces of Art?

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: One of the most valuable items in Rome is a bathtub that has been estimated to be worth $2 billion. The bathtub — more technically known as a “porphyry basin” — is today housed in the round hall in the Pio Clementino Museum. It was commissioned by the first-century Roman emperor Nero for his famously decadent architectural vanity project the Domus Aurea (Golden House). Built entirely of purple stone, the basin weighs more than 1,000 pounds. At a Bible conference, Eric Vanden Eykel, an associate professor of religion at Ferrum College, and I discussed the bathtub and its hefty price tag. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 27, 2022]

The reason it is so expensive, Vanden Eykel told me, is that it “was made from an extremely rare and therefore expensive marble called ‘imperial porphyry.’ Nero and other emperors liked this stone because of its deep and distinctive purple shade, but it also didn’t hurt that it was exclusive and extremely hard to come by.” All imperial porphyry mined in the ancient world came from a single, remote quarry in the eastern part of Roman Egypt called the Mons Porphyrites. It was discovered in 18 B.C. when a Roman soldier named Caius Cominius Leugas noticed a hard purple-red rock in the desert. Technically porphyry (which just means “purple” in Greek) is an igneous rock containing coarse grained crystals. Most imperial purple marble was used as an accent stone in tiled floors or on columns. You can find it fashioned into vases or busts, but the basin from Nero’s Golden House is exceptionally large and heavy. It’s almost certainly the largest single intact piece of porphyry marble that exists today. The mine established at Mons Pophryites was used continuously until A.D. 600, when the Romans lost control of Egypt.

After it was extracted from the mines — which was no mean feat! — the material had to be transported. The journey began with a lengthy overland journey from the mine to the Nile. At Coptos, the marble boarded a ship up the river and carried on across the Mediterranean making stops along the way. The final leg of the journey, from the port of Ostia to the City of Rome also took place over land. Even for those not transporting heavy marble this was a lengthy journey that could take as long as 10 weeks. As Incunabula has put it on Twitter: “Imperial porphyry signaled not just power and prestige, but also that the Roman Empire could accomplish the near impossible: Cutting and quarrying the immensely hard rock, and transporting it 1000s of kilometerss from the Egyptian desert to Rome was an awe-inspiring feat of engineering.”

It was the expense of moving the stuff that made imperial porphyry so expensive and exclusive. Vanden Eykel told me that imperial marble is immediately recognizable because of its distinctive marble hue. It signifies wealth and status. Just as having a white alligator Hermes Birkin says that you have connections and $150,000 to burn on a handbag, porphyry marble signaled to your guests that you were someone of import. What says that more, said Vanden Eykel, than “a gargantuan porphyry bathtub?” The only other porphyry objects of similar scale were tombs and coffins: Nero, the Holy Roman Emperors, and even Napoleon all chose it for their final resting places. Napoleon had to make do with a common red marble.

Like other luxury products, imperial porphyry were regularly imitated. Rosso antico marble (also known as Marmor Taenarium), a beautiful red marble mined in the southern Peloponnese, was one such imitator. It was used, as Lorenzo Lazzarini notes, “as a substitute of the red Egyptian porphyry.” Though it is beautiful, rosso antico lacks the speckles and deep purple of the Egyptian marble. If you wanted to get the imperial porphyry look today, you might try a rosso impero instead.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024