HEALTH CARE IN ANCIENT ROME

Surgical instruments found at Pompeii include scalpels, forceps and needles. People with health problems generally went to a temple rather than a doctor. Payment consisted of an offering to the God Asclepius. Some temple had sanctuaries staffed by priests who dispensed treatments, which usually consisted of a solemn ceremony and an overnight stay in a sacred dormitory. Treatments were often based on analysis of dreams the patient had while the dormitory.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: As Christian Laes has shown in his book “Disabilities in Roman Antiquity”, bodily disfigurement of one kind or another was almost the norm in the ancient world. People performed manual work were especially susceptible to hand and eye injuries. While blacksmiths wore eye patches to protect at least one eye while they worked, there was very little protective equipment available to the non-soldier and even less proficient medical care for the injured. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, March 10, 2018]

There were several factors that influenced the development of medicine in ancient Greece. First, there was the potent force of religion with its gods and goddesses who dealt with healing, death and pestilence. Then there was the influence of trading contacts such as Egypt (which had learned much from its mummification practices) and Mesopotamia (which had published comprehensive medical documents on clay tablets well before 1000 B.C.). From these and other Eastern areas, the Greeks also developed an encyclopedic range of herbal medicines. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

“To cap it off, there was the sad result of war - a variety of wounds and amputations caused by arrows, swords, spears and accidents- and described so vividly and accurately in Homer's Iliad. Just dealing with these casualties provided lots of experience and practical information applicable elsewhere. Although Greek religion frowned on human dissection in the Archaic and Classical periods, after the founding of the Alexandrian School that changed. Physicians and researchers made advances in some areas that were not surpassed until the 18th Century.” |

RELATED ARTICLES:

HEALTH IN ANCIENT ROME: LONGEVITY, IDEAS, ISSUES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

DISEASES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN MEDICINES europe.factsanddetails.com

GRECO-ROMAN HEALING TEMPLES: ASKLEPIOS, DREAM TREATMENTS, MIRACULOUS CURES factsanddetails.com;

HEALTH IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HEALTH CARE IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

DOCTORS AND HEALTH CARE PRACTITIONERS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Greek and Roman Medicine” by Helen King (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Medicine” (Sciences of Antiquity) by Vivian Nutton (2012) Amazon.com;

"The Oxford Handbook of Science and Medicine in the Classical World by Paul Keyser and with John Scarborough (2018) Amazon.com;

“Medicine and Healthcare in Roman Britain" (Shire Archaeology) by Nicholas Summerton (2008) Amazon.com;

“Roman Medicine and Military: Topics in Healing and Power” by Elizabeth Legge (2025) Amazon.com;

“Women Healing/Healing Women: The Genderisation of Healing in Early Christianity” by Elaine Wainwright (2017) Amazon.com;

“Women Physicians in Ancient Rome”, Kindle Edition, by Elizabeth Legge (2023) Amazon.com;

“Contested Cures: Identity and Ritual Healing in Roman and Late Antique Palestine” by Megan Nutzman (2024) Amazon.com;

“A Cabinet of Ancient Medical Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Healing Arts of Greece and Rome” by J.C. McKeown (2016) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Greece and Rome (Blackwell) by Georgia L. Irby (2016) Amazon.com;

“Pharmacy and Drug Lore in Antiquity: Greece, Rome, Byzantium”by John Scarborough | (2024) Amazon.com;

“Greco-Roman Medicine and What It Can Teach Us Today” (2021) by Nick Summerton Amazon.com;

“Death and Disease in the Ancient City” by Valerie Hope and Eireann Marshall (2011) Amazon.com;

“Pox Romana: The Plague That Shook the Roman World by Colin Elliott (2024) Amazon.com;

“Thorns in the Flesh: Illness and Sanctity in Late Ancient” by Andrew Crislip (2012) Amazon.com;

“Disability in Antiquity” by Christian Laes Amazon.com;

“Prosthetics and Assistive Technology in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Jane Draycott (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Galen” by R. J. Hankinson (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Prince of Medicine: Galen in the Roman Empire” by Susan P. Mattern Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Medical Treatments in Ancient Rome

Common treatments included recommendations, exercise, medicine purging and bleeding. Broken arms and legs were often not set properly, causing limps and physical difficulties that remained with a person for their entire life. Wounds and injuries received in war, in childhood, or in domestic and professional accidents were rarely stitched, producing nasty scars that also remained a lifetime.

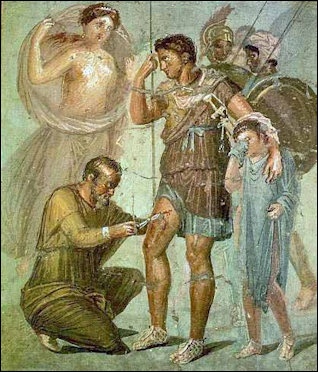

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Medicine in classical antiquity was a collection of beliefs, knowledge, and experience. What we know of early medical practice is based upon archaeological evidence, especially from Roman sites—medical instruments, votive objects, prescription stamps, etc. — and from ancient literary sources. Most of the literary evidence is preserved in treatises attributed to the Greek physician Hippocrates (ca. 460–370 B.C.) and the Roman physician Galen. “From the earliest times, treatments involved incantations, invoking the gods, and the use of magical herbs, amulets, and charms. “In ancient Greece and Rome, Asklepios was revered as the patron god of medicine. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar,Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Archaeology magazine reported: An experienced surgeon treating a soldier on the island of Thasos tried everything to alleviate his patient’s debilitating infection, even performing a complex procedure that entailed boring holes in his skull. The man, who was buried at the site of Palaiokastro between the 4th and 7th centuries A.D., was probably a mounted archer in the Roman army. His severe infection may have been caused by a ruptured eardrum or possibly a tumor. The procedure was ultimately unsuccessful despite the doctor’s skill. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July-August 2020]

Galen

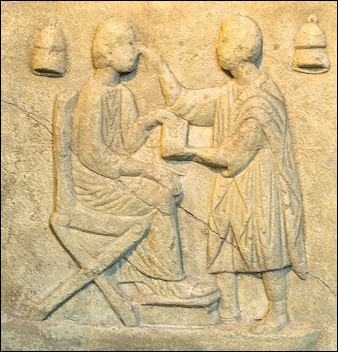

eye examination in ancient Rome

Galen (A.D. 130-200), a physician from Pergamum in Asia Minor, is considered the father of medicine. For 1,400 years, doctors in ancient Rome, Medieval Europe and the great Islamic empires based their treatment on literature written by Galen, who saw the inside of a body only a few times and the closest he had ever come to examining a cadaver (a practice considered taboo in Greek and Roman times) was looking at a skeleton picked clean by vultures on the side of a road. His anatomy texts were based primarily on the dissections of pigs and monkeys. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,"]

Galen began studying medicine at the age of fifteen and continued his studies until he was 28 with professors of medicine in Smyrna, Corinth and Alexandria. His first job as a doctor was patching up maimed and wounded gladiators in Pergamum, and he probably learned more practical information from this job than he did doing anything else. Later he treated the rich in Rome and became the court physician of philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius."

Galen was one of the most prolific writers of antiquity. He produced five hundred treatises in Greek — on anatomy, physiology, rhetoric, grammar, drama and philosophy. More than a hundred of these works survive, including a treatise indexing his own writings."

Galen once conceded if "he had not called on the mighty in the morning and dined with them in the evening" he probably wouldn't have had much success. Despite his notoriety and wealth he despised material possessions and once said all he really needed in life was two garments, two slaves, and two sets of utensils.

See Separate Article: FATHERS OF GRECO-ROMAN MEDICINE: HIPPOCRATES, GALEN AND THE GOD ASCLEPIUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Health Care Practitioners in Antiquity

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Drug sellers, root cutters, midwives, gymnastic trainers, and surgeons all offered medical treatment and advice. In the absence of formal qualifications, any individual could offer medical services, and literary evidence for early medical practice shows doctors working hard to distinguish their own ideas and treatments from those of their competitors. The roots of Greek medicine were many and included ideas assimilated from Egypt and the Near East, particularly Babylonia.” [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar,Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Medical practitioners frequently traveled from town to town, but there is little evidence to suggest that they were hired to provide free care for the general population. In Rome, for instance, where traditional Italian medicine competed with foreign imports, many doctors were Greek. Anyone could practice medicine, although most were free citizens. Medical training in ancient Greece and Rome might take the form of an apprenticeship to another doctor, attendance at medical lectures, or even at public anatomical demonstrations. \^/

“Two of the most famous healing sanctuaries sacred to the god were at Epidauros and on the island of Kos. The success of the cult of Asklepios in antiquity was due to his accessibility—although the son of Apollo, he was still human enough to attempt to cancel death. Those who sought a cure in the temples erected to him were subjected to ritual purifications, fasts, prayers, and sacrifices. A central feature of the cult and the process of healing was known as incubation, during which the god appeared to the afflicted one in a dream and prescribed a treatment.” \^/

Doctors in Ancient Rome

Roman doctor

Some physicians were well paid in the Imperial period, if we may judge by those attached to the court. Two of these left a joint estate of $1,000,000, and another received from the Emperor Claudius a yearly stipend of $25,000. In knowledge and skill in both medicine and surgery they do not seem to have been much behind the practitioners of two centuries ago. Surgery seems to have developed in early times chiefly in connection with the necessary treatment of wounds in warfare. Medicine, apart from religious rites to gods of health or disease, must have been limited for a long period to such household remedies and charms as Cato describes in his work on farming. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

The first foreign surgeon, a Greek, came to Rome in 219 B.C. Physicians and surgeons were as a rule slaves, freedmen, or foreigners, especially Greeks. The great number of Greek medical terms in use today testifies to Greek influence in the history of medicine. Caesar gave citizenship to Greek physicians who settled in Rome, and Augustus granted them certain privileges. The great houses were apt to have carefully trained physicians among their own slaves. We can judge of ancient medical and surgical methods from books on the subject that have come down to us, such as those of Celsus, a Roman who wrote in the first century of our era, and Galen, the great Greek physician who came to Rome in the reign of Hadrian. Surgical instruments, too, have been found at Pompeii and elsewhere. Galen says that by his time surgery (chirurgia) and medicine (medicina) had been carefully distinguished. |+|

There were oculists, dentists; and other specialists, and occasionally women physicians. In the second century of our era many cities had regularly salaried medical officers for the treatment of the poor, and gave them rooms for offices. By Trajan’s time there were regular army doctors attached to the legions, as there probably had been before, though we know little of them. There were no medical schools. Physicians took pupils, and let them go with them on their rounds. Martial complains of the many cold hands that felt his pulse when a doctor called with a train of pupils.”

Roman Doctor Found Far from Home in Hungary

According to Archaeology magazine: “A Roman doctor traveling far from home 2,000 years ago was buried with his specialized instruments. A wooden box found at the physician’s feet contained an array of high-quality copper-alloy and silver medical tools, including needles, tweezers, forceps, and scalpels with replaceable blades. Experts believe the man had been trained in the Roman Empire but ventured beyond its borders to treat someone when he died unexpectedly and was interred near present-day Jászberény.[Source: Archaeology magazine, August 2023]

The medical tools include high-quality scalpels "suitable for surgical procedures". Brendan Rascius wrote in the Miami Herald: The skeletal remains of the doctor, which include an intact skull and leg bones, were found alongside a complete set of medical tools, researchers said. The equipment was of extremely high quality and included pliers, needles and scalpels outfitted with replaceable blades, researchers said. A grinding stone, which could have been used to mix medicines, was also uncovered. Only one other comprehensive collection of similar ancient Roman medical equipment has ever been found (in Pompeii), making the discovery extremely rare, researchers said. [Source: Brendan Rascius, Miami Herald, April 27, 2023]

The skeleton of the "doctor" showed he was a man aged about 50 or 60 years old when he died. At the time he died, in the first century A.D., the part of Hungary he was found in wasn't part of the Roman Empire. It was ruled by Sarmatians of the Iazyges tribe and acted as a buffer state between the Roman territories and the Dacians farther north. [Source Tom Metcalf, Live Science, May 5, 2023]

Ancient Roman Spas

Romans were also one of the first people to credit mineral water with healing powers. The Greeks had known about mineral water but they considered it unhealthy. Romans drank and bathed in it and sought relief in mineral water for liver and kidney trouble and a host of other ailments. The Romans set up baths at natural hot springs in Baiae (near Pompeii) and Badoit and Vittel in what is now France. Julius Caesar bathed at Vichy. Later these were abandoned in favor of cold water resorts like Gabii near Rome.

The cold water bath of Chiancian Terme in Tuscany, known promoting "a healthy liver," consisted of various buildings arranged around a 60-x-130-foot swimming pool paved with roof tiles. At one end of the pool was a podium, presumable for a statue of a god or emperor. The pool was three-feet deep, adequate for bathing but not swimming, and was 64̊F.

Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology magazine: Around A.D. 60, at Aquae Sulis, the site of natural hot springs in what is now Bath, England, the Romans built a huge temple and spa complex that became a center for both pilgrimage and health. There, Romans and local Britons socialized and bathed, hoping to heal a host of ailments such as rheumatism, arthritis, and gout. They also worshipped the Romano-Celtic healing goddess Sulis Minerva. The Aquae Sulis springs had already been host to centuries — and possibly millennia — of ceremonies held by Bronze and Iron Age communities. Even after the destruction of the Roman baths in the sixth century A.D., Aquae Sulis’ legacy continued. The health-giving properties of the springs were well known in Britain throughout the Middle Ages, and by the seventeenth century, Bath was the place to see and be seen. It became common for visitors to drink the sulfurous thermal waters, a practice known as “taking the cure.” Some still engage in this activity, seeking its purported health benefits. [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2021

Roman-Era Medical Center Found in Turkey

Roman catheters

In January 2023, archaeologists announced that had found 348 1,800-year-old artifacts linked to medicine at the site of Allianoi, an ancient town that also hosted a large spa-like bath in what is now Turkey. The huge number of artifacts indicates that the site once featured an ancient medical center. The instruments were discovered during rescue excavations that were carried out between 1998 and 2006, before the construction of a dam that flooded the site. Most of the artifacts, which have been studied over the years, were found within two buildings in a larger complex. "Allianoi was, perhaps, one of the earliest known cases of an organized, group medical practice," Sarah Yeomans, an archaeologist at St. Mary's College of Maryland, wrote in the abstract of a paper she presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Classical Studies, held in January 2023 in Chicago. "The categories and variety of surgical instruments indicate that relatively sophisticated surgical procedures were undertaken at Allianoi.” [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, January 31, 2024]

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science. The artifacts included instruments used to remove hemorrhoids, as well as tools to extract bladder and kidney stones. Other instruments indicate that cataract surgery, or the removal of a person's cloudy eye lens, and the suturing of wounds may also have taken place at the center. The researchers don't know how many medical practitioners worked at the site at any one time, "though it was likely dozens or more, depending on the time period," Yeomans told Live Science.

However, while these health care workers may have gathered in the same spot, that doesn't mean they were colleagues. "Please keep in mind that this wasn't an organized 'practice' in the sense that they were all working for a single business, like today," Yeomans said. "Rather, it would have been more like Harley Street in London in the 19th century where all sorts of practitioners or specialists set up shop in the same location."

Daniş Baykan, an archaeology professor at Trakya University in Turkey who was not involved with the new research but completed his doctoral thesis on Allianoi, told Live Science that he had previously made similar findings. Baykan also found that the instruments were used for a variety of procedures. He suggested that the ancient doctor Galen, who lived from around A.D. 129 to 216 and resided in nearby Pergamon, may have practiced at Allianoi. Ancient records indicate that Galen successfully performed surgeries on injured gladiators, and he may have undertaken these at Allianoi, Baykan suggested.

Patty Baker, a senior lecturer of classical and archaeological studies at the University of Kent in the U.K. who was also not involved with the new research, said it is not surprising that the facility was located near a bath. In the Roman world, "a lot of medical tools are found in bath buildings because they were places people would go for health care," Baker told Live Science.

Baker added that while it's possible that a group of physicians worked at the site, we can't say for certain based on the current evidence.

Dental Care in Ancient Rome

copy of a Roman denture

In Roman times. men lost an average of 6.6 teeth before they died, compared to 2.2 teeth 30,000 years ago and 3.5 teeth in 6,500 B.C.

The Romans filled cavities with gold, replaced missing teeth with bridgework and promoted dental hygiene. Still a fair of amount of ignorance prevailed. Pliny the Elder wrote that tooth aches could be cured by spitting on the mouth of frog under a full moon, chanting "Frog, go and take my toothache with thee!"

Many ancient people believed that tooth pain was caused by creatures called toothworms. Describing a remedy for such creatures a physician to Emperor Claudius wrote: "Suitable against toothache are fumigations made with the seeds of Hyoscyamus [probably belladonna] scattered on burning charcoal; these must be followed by rinsing the mouth; in this way, sometimes, as it were, small worms are expelled."

The Romans used human urine in mouthwashes and tooth paste and as a detergent. Portuguese urine was regarded as being of the best quality. Urine was believed to make teeth white and hold them in place in the gums. For a toothache Pliny also advised people to rinse their teeth with a mixture of vinegar and boiled frogs.

Roman-Era Medical Scholars on Surgical Instruments

John Stewart Milne wrote in “Surgical Instruments in Greek and Roman Times”: “Rufus of Ephesus (98-117 A.D.) has left little to interest us for our particular purpose, as he merely mentions, without describing, a few instruments, all of which are already known to us from other sources. [Source: “Surgical Instruments in Greek and Roman Times” by John Stewart Milne, M.A., M.D. Aberd. Oxford: Clarendon Press (1907) ^*^]

“Aretaeus of Cappadocia has left us a work on Acute and Chronic Diseases. He has few references to instruments, but such as they are they are interesting, as he names some which are given by no other author. He has a tantalizing allusion to a work by himself on surgery which has not been preserved. ^*^

“Galen (130-200 A.D.) was a most voluminous writer, much of whose work remains and teems with matter of interest to us. Much information about instruments is to be gained from even his purely anatomical writings. ^*^

surgical instruments

“Oribasius (325 A. D.) wrote an encyclopaedia of medicine, which is called Collecta Medicinalia, in seventy books, only about one third of which remain. This is the most interesting of his works from our point of view, but he has left also a synopsis of the encyclopaedia and a sort of first aid manual. ^*^

“Soranus of Ephesus has left us a most valuable treatise on obstetrics and gynaecology, which, though written only for midwives, contains many interesting references to instruments such as the speculum, uterine sound, cephalotribe, decapitator, and embryo hook. He lived in the reign of Trajan. Some of the chapters, of which the Greek is lost, have been preserved to us by his abbreviator Moschion..^*^

“Caelius Aurelianus Siccensis, an African of the fourth or fifth century, translated the works of Soranus, both those on gynaecology and those on general diseases, and he preserves some of Soranus which we would not otherwise possess; but he writes in a barbarous Latin which, like the Latin of some other African writers on medical subjects, is calculated to cause great pain to anyone not familiar with this particular style. ^*^

“Marcellus Empiricus (300 A.D.) wrote a work on pharmacy, of large size but little value, and in a poor style. There are a few passages bearing on implements of minor surgery. A good deal is copied from Largus. ^*^

“Theodorus Priscianus, alias Octavius Horatianus, lived in the fourth century and has left a work, in three books, called Euporiston. It is a compilation in African Latin of extracts from Galen, Oribasius, &c. The style of the Latin is so barbarous that it really must be seen to be believed. There is a little information to be gathered about minor instruments.

“There are a few interesting references to instruments in the works of the early Christian fathers. Tertullian is the only one of these I can claim to have systematically searched, but in one of his sermons he refers to no less than four surgical instruments, one of which is not described by any other author. ^*^

Asclepius, the Healing God

Marianne Bonz wrote for PBS’s Frontline: “The son of Apollo by a mortal woman, Asclepius was taken by his divine father at birth and apprenticed to a wise centaur (a mythical creature, half man and half horse). This centaur, whose name was Chiron, taught Asclepius the healing arts so that he could reduce the sufferings of mortals. With his miraculous cures, Asclepius quickly earned great fame. Motivated by compassion, he even succeeded in restoring the dead to life. But this proved his undoing. Hades complained to Zeus that if this were allowed to continue, the natural order of the universe would be subverted. Zeus agreed and struck Asclepius down with a thunderbolt. In some versions of the story, Asclepius was transformed into a star after his death. [Source: Marianne Bonz, Frontline, PBS, April 1998. Bonz was managing editor of Harvard Theological Review. She received a doctorate from Harvard Divinity School, with a dissertation on Luke-Acts as a literary challenge to the propaganda of imperial Rome. ]

Asclepius

“Asclepius was an immensely popular god, originally in Greece but later also in Rome. By the fourth century before the common era, he had established a number of sanctuaries in Greece, the most important ones being in Cos and Epidauros. Early in the third century B.C., his cult was brought to Rome after the city had been struck by a plague. Asclepius's medical knowledge and divine healing powers fostered two distinct traditions within the Greek world. On the one hand, he served as a divine mentor to the doctors who treated patients at his sanctuary at Cos. On the other hand, at the sanctuary of Epidauros, the god performed miraculous cures in response to the direct petitions of suppliants.

“In the early Roman imperial era, Asclepius assumed an even greater religious importance. He had become a savior god. The physically or emotionally afflicted received long-term care and guidance at his sanctuaries, and in return they devoted themselves to his worship and service.

“The most famous of devotee of Asclepius during the Roman imperial period was the rhetor and sophist (professional public speaker) Aelius Aristides. Having just embarked on his public career, Aristides was stricken by a complete physical and mental breakdown. After seeking the help of another god to no avail, he visited the shrine of Asclepius in his adoptive city of Smyrna.

“During this visit, the god appeared to Aristides in a dream-vision, and this encounter changed his life. Asclepius not only prescribed treatments for his chronic bouts of illness, the god also offered guidance for the conduct of all aspects of his life. Thereafter, Aristides placed himself and his career under the god's protection, making numerous extended visits to the renowned Asclepius sanctuary in Pergamon. In his autobiographical narrative of his numerous encounters with the god, Aristides reveals his special relationship with Asclepius by most often addressing the god as "Savior."

See Separate Article: FATHERS OF GRECO-ROMAN MEDICINE: HIPPOCRATES, GALEN AND THE GOD ASCLEPIUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Healing Temples of in the Greco-Roman Era

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Two of the most famous healing sanctuaries sacred to the god were at Epidauros and on the island of Kos. The success of the cult of Asklepios in antiquity was due to his accessibility—although the son of Apollo, he was still human enough to attempt to cancel death. Those who sought a cure in the temples erected to him were subjected to ritual purifications, fasts, prayers, and sacrifices. A central feature of the cult and the process of healing was known as incubation, during which the god appeared to the afflicted one in a dream and prescribed a treatment. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar,Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004]

Strabo wrote in “Geographia” (c. A.D. 20): “On the road between the Tralleians and Nysa is a village of the Nysaians, not far from the city Acharaca, where is the Plutonium, with a costly sacred precinct and a shrine of Pluto and Kore, and also the Charonium, a cave that lies above the sacred precinct, by nature wonderful; for they say that those who are diseased and give heed to the cures prescribed by these gods resort there and live in the village near the cave among experienced priests, who on their behalf sleep in the cave and through dreams prescribe the cures. These are also the men who invoke the healing power of the gods. And they often bring the sick into the cave and leave them there, to remain in quiet, like animals in their lurking-holes, without food for many days. And sometimes the sick give heed also to their own dreams, but still they use those other men, as priests, to initiate them into the mysteries and to counsel them. To all others the place is forbidden and deadly. [Source: Strabo, The Geography of Strabo: Literally Translated, with Notes, translated by H. C. Hamilton, & W. Falconer, (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857)

Hygieia

Philostratos wrote in “Life of Apollonios of Tyana” (c. A.D. 190): “When the plague broke out at Ephesos and there was no stopping it, the Ephesians sent a delegation to Apollonios asking him to heal them. Accordingly, he did not hesitate, but said, "Let's go," and there he was, miraculously, in Ephesos. Calling together the people of Ephesos, he said, "Be brave; today I will stop the plague." Then he led them all to the theater where the statue of the God-Who-Averts-Evil had been set up. [Source: Philostratus, the Athenian, “The Lives of the Sophists,” translated by Wilmer Cave Wright, (London: Wm. Heinemann, 1922)

“In the theater there was what seemed to be an old man begging, his eyes closed, apparently blind. He had a bag and a piece of bread. His clothes were ragged and his appearance was squalid. Apollonios gathered the Ephesians around him and said, "Collect as many stones as you can and throw them at this enemy of the Gods."The Ephesians were amazed at what he said and appalled at the idea of killing a stranger so obviously pitiful, for he was beseeching them to have mercy on him. But Apollonios urged them on to attack him and not let him escape. When some of the Ephesians began to pitch stones at him, the beggar who had his eyes closed as if blind suddenly opened them and they were filled with fire. At that point the Ephesians realized he was a demon and proceeded to stone him so that their missiles became a great pile over him. After a little while Apollonios told them to remove the stones and to see the wild animal they had killed. When they uncovered the man they thought they had thrown their stones at, they found he had disappeared, and in his place was a hound who looked like a hunting dog but was as big as the largest lion. He lay there in front of them, crushed by the stones, foaming at the corners of his mouth as mad dogs do.”

See Separate Article: GRECO-ROMAN HEALING TEMPLES: ASKLEPIOS, DREAM TREATMENTS, MIRACULOUS CURES factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024